5.5 ESP—

162

LOQ 5-

extrasensory perception (ESP) the controversial claim that perception can occur apart from sensory input; includes telepathy, clairvoyance, and precognition.

The river of perception is fed by streams of sensation, cognition, and emotion. If perception is the product of these three sources, what can we say about extrasensory perception (ESP), which claims that perception can occur apart from sensory input?

The answer depends in part on who you ask. Nearly half of all Americans surveyed believe we are capable of extrasensory perception (AP, 2007; Moore, 2005). The most testable and, for this chapter, most relevant ESP claims are

telepathy: mind-

to- mind communication. clairvoyance: perceiving remote events, such as a house on fire in another state.

precognition: perceiving future events, such as an unexpected death in the next month.

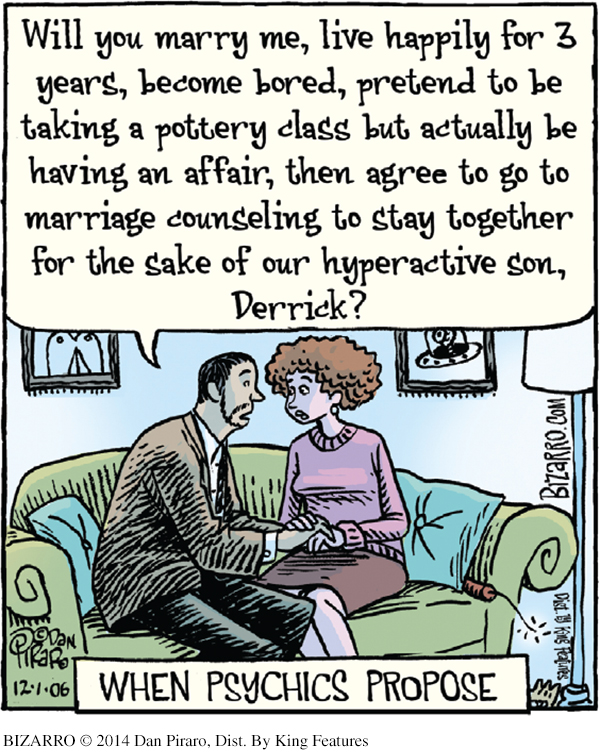

Closely linked is psychokinesis, or “mind over matter,” such as using mind power alone to raise a table or affect the roll of a die. (The claim is illustrated by the wry request, “Will all those who believe in psychokinesis please raise my hand?”)

Most research psychologists and scientists—

What about the hundreds of visions offered by psychics working with the police? These have been no more accurate than guesses made by others (Nickell, 1994, 2005; Radford, 2010; Reiser, 1982). Their sheer volume does, however, increase the odds of an occasional correct guess, which psychics can then report to the media.

Are everyday people’s “visions” any more accurate? Do our dreams predict the future, or do they only seem to do so when we recall or reconstruct them in light of what has already happened? After aviator Charles Lindbergh’s baby son was kidnapped and murdered in 1932, but before the body was discovered, two psychologists invited people to report their dreams about the child (Murray & Wheeler, 1937). How many replied? 1300. How many accurately saw the child dead? 65. How many also correctly anticipated the body’s location—

Given the billions of events in the world each day, and given enough days, some stunning coincidences are sure to occur. By one careful estimate, chance alone would predict that more than a thousand times a day, someone on Earth will think of another person and then, within the next five minutes, learn of that person’s death (Charpak & Broch, 2004). Thus, when explaining an astonishing event, we should “give chance a chance” (Lilienfeld, 2009). With enough time and enough people, the improbable becomes inevitable.

“A person who talks a lot is sometimes right.”

Spanish proverb

When faced with claims of mind reading or out-

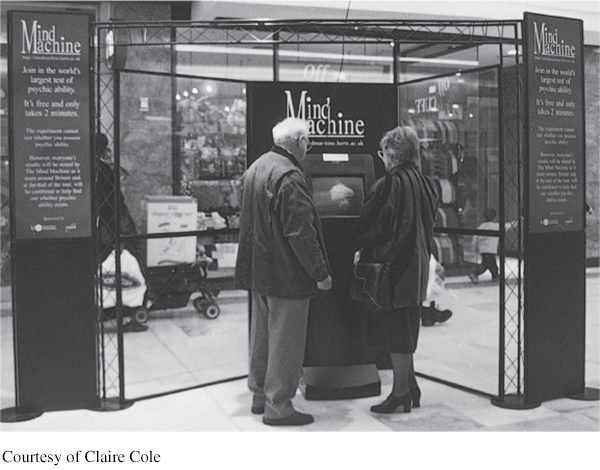

How might we test ESP claims in a controlled, reproducible experiment? An experiment differs from a staged demonstration. In the laboratory, the experimenter controls what the “psychic” sees and hears. On stage, the “psychic” controls what the audience sees and hears.

Daryl Bem, a respected social psychologist, once joked that “a psychic is an actor playing the role of a psychic” (1984). Yet this one-

Bem’s research survived critical reviews by a top-

163

Anticipating such skepticism, Bem has made his research materials available to anyone who wishes to replicate his studies. Multiple attempts have met with minimal success, and the debate continues (Bem et al., 2014; Galak et al., 2012; Ritchie et al., 2012; Wagenmakers, 2014). Regardless, science is doing its work. It has been open to a finding that challenges its assumptions. And then, through follow-

One skeptic, magician James Randi, has had a long-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 5.18

•If an ESP event occurred under controlled conditions, what would be the next best step to confirm that ESP really exists?

ANSWER: The ESP event would need to be reproduced in other scientific studies.

* * *

Most of us will never know what it is like to see colorful music, to be incapable of feeling pain, or to be unable to recognize the faces of friends and family. But within our ordinary sensation and perception lies much that is truly extraordinary. More than a century of research has revealed many secrets of sensation and perception. For future generations of researchers, though, there remain profound and genuine mysteries to solve.