1.12 THIS IS HOW WE DO IT: Is arthroscopic surgery for arthritis of the knee beneficial?

1.12 THIS IS HOW WE DO IT: Is arthroscopic surgery for arthritis of the knee beneficial?

Sometimes we may think that we “know” something when in fact there is no strong evidence supporting that belief. It can be particularly difficult to question ideas that are widely accepted. That’s when the power of a randomized, well-

Consider, for example, the efficacy of a common knee surgery for arthritis. In this arthroscopic surgery, surgeons make several small incisions and insert a tiny, flexible tube into the knee in order to see inside the joint. As a treatment for arthritis, the surgeon may then remove or sand down debris and damaged cartilage. She may also flush out the debris and other materials from the knee joint.

Until very recently, this type of surgery was performed on more than 650,000 people in the United States each year—

How could you determine whether a particular type of surgery is effective?

The general approach that the researchers took was straightforward. From a large group of volunteers who suffered from osteoarthritis of the knee, some received arthroscopic surgery, while others received a placebo surgery. The researchers then evaluated individuals’ knee function and degree of pain relief over the course of the two years following surgery.

Wait a minute … what?

Yes. After recruiting 180 volunteer patients who were candidates for arthroscopic surgery for their arthritis, the researchers randomly assigned them to one of three groups. Two of the groups would undergo arthroscopic surgery, while the third group would receive the placebo surgery. The participants did not know which group they were in, but all of them did understand that they might undergo only the placebo surgery. They all signed an “informed consent” form stating: “I realize that I may receive only placebo surgery. I further realize that this means that I will not have surgery on my knee joint. This placebo surgery will not benefit my knee arthritis.”

How does general scientific literacy—

The patients were randomly assigned to one of the three groups. This occurred only after they were in the operating room, at which point the surgeon (one surgeon performed all the operations) was given an envelope indicating which treatment each patient was to receive. The treatments included:

- 1. Arthroscopic surgery with debridement: The surgeon made the incisions and irrigated the knee joint with 10 liters of fluid, and then shaved, trimmed, and smoothed (that is, debrided) the cartilage.

- 2. Arthroscopic surgery with lavage: The surgeon made the incisions and irrigated the knee joint with 10 liters of fluid, as in the first group, but did not debride. Any debris that could be flushed out was removed (the process of “lavage”).

- 3. Placebo surgery: The surgeon made the same three incisions as in the first two groups, and then asked for all instruments and manipulated the knee as if performing arthroscopic surgery with debridement. The surgeon also splashed saline to simulate lavage.

20

In all three treatments, patients spent the night in the hospital, cared for by nurses who did not know which treatment group they were in.

How did the researchers decide whether the arthroscopic surgery was effective?

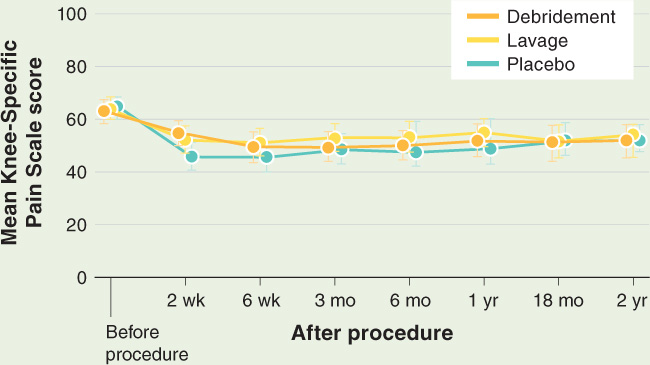

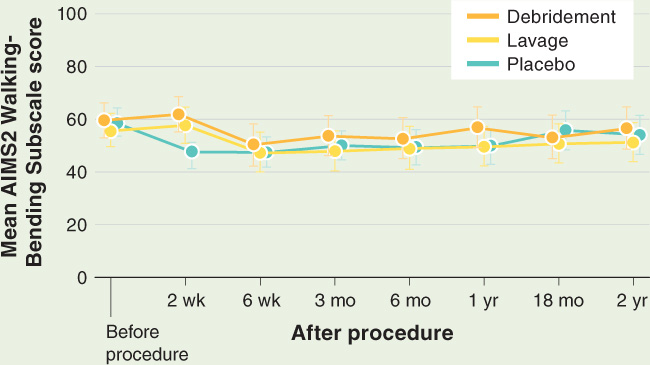

The researchers evaluated the effectiveness of the surgery at seven points over the next two years. The evaluations included patients’ self-

Why do you think these two different measures were used?

Pain scores were on a scale of 0–

Knee function measures were also on a scale of 0–

What is the take-

At no point following surgery was pain reduced or knee function improved in patients receiving either type of arthroscopic surgery when compared with those undergoing the placebo surgery. At two years, for example, the pain scores were:

| Patient Group | Mean Pain Score |

|---|---|

| 1. Debridement | 51 ± 23 |

| 2. Lavage | 54 ± 24 |

| 3. Placebo | 52 ± 24 |

What conclusions can you draw from these results?

Publishing their results in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers summarized their conclusions succinctly: “This study provides strong evidence that arthroscopic lavage with or without débridement is not better than and appears to be equivalent to a placebo procedure in improving knee pain and self-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 1.12

In a well-

Describe how researchers designed and used a well-

21