9.4: Complex-appearing behaviors don’t require complex thought in order to evolve.

Why do humans and other animals have sex? Is it because they are thinking, robot-

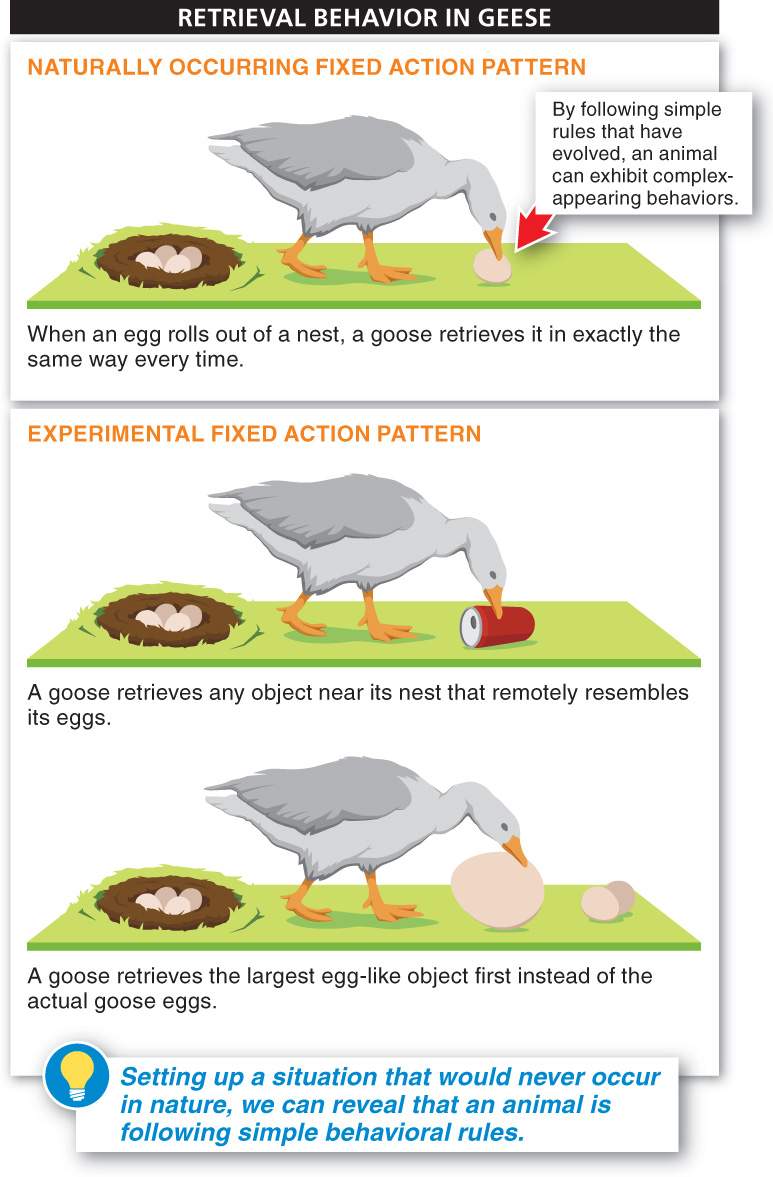

In actuality, natural selection produces organisms that exhibit relatively simple behaviors in response to certain situations or environmental conditions—

Q

Question 9.3

Do animals consciously act in order to improve their reproductive success?

We can investigate experimentally whether natural selection sometimes results in such evolutionary short cuts—

To test the limits of the retrieval behavior, researchers began putting larger and larger models of eggs outside the nests. When given a choice between an actual goose egg and an artificial egg the size of a basketball, the goose always tried to retrieve the giant egg. Rather than keeping tabs on their eggs, geese seem to be following a rule of thumb to retrieve any nearby egg-

372

Taking an evolutionary approach to the study of the behavior of animals, including humans, is not new. Charles Darwin wrote in On the Origin of Species: “In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation.” And in the past several decades, Darwin’s prediction has increasingly proved true. In a synthesis of evolutionary biology and psychology, researchers taking an approach called “evolutionary psychology” have begun to view the human brain and human behaviors, including emotions, as traits produced by natural selection, selected as a result of their positive effects on survival and reproduction. So, too, has the evolutionary approach to studying behavior begun to influence the field of economics. The 2002 Nobel prize for economics was awarded to researchers who used insights from evolutionary biology and psychology in their analyses of human decision making.

In the rest of this chapter, working from the understanding that organisms’ traits, including their behaviors, have evolved by natural selection, we examine the question of why organisms behave as they do. We begin with an exploration of selfishness and cooperation in animals—

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 9.4

If certain behavior in natural situations usually increases an animal’s relative reproductive success, the behavior will be favored by natural selection. The natural selection of such behaviors does not require the organism to consciously try to maximize its reproductive success.

Do animals consciously try to maximize their reproductive success? Explain.

373