9.6: Apparent altruism toward relatives can evolve through kin selection.

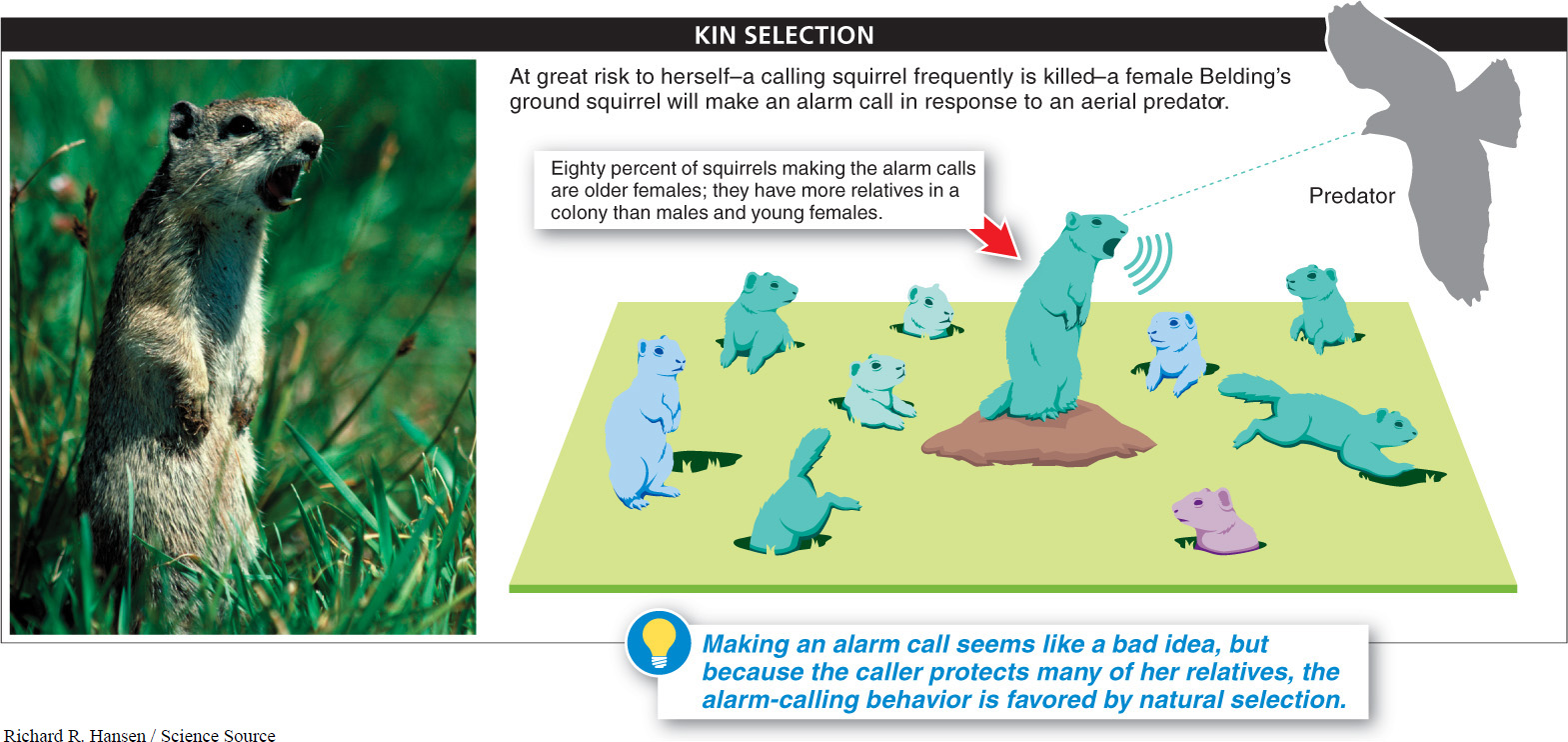

The grasslands of the western United States are home to large colonies of Belding’s ground squirrels, living in underground burrows. Because the colonies are as large as hundreds or thousands of individuals, they attract many birds of prey, which succeed in killing a squirrel in about 10% of attempts. Squirrels have a system for reducing predation risk that resembles a neighborhood watch program. When an aerial predator approaches, it is common for one squirrel, standing on top of a burrow, to produce a loud whistle-

Some squirrels see predators and make alarm calls, while other squirrels see predators and keep their mouths shut. Why would any squirrel make an alarm call? And which squirrels are most likely to engage in this altruistic-

375

These differences reveal that alarm calling is about protecting relatives. The more kin an individual is likely to have, the more likely that individual is to sound the alarm. Males travel long distances to live in new colonies shortly after reaching maturity, so most adult males don’t live near their parents, siblings, or any other relatives except their own offspring. Females, on the other hand, remain near the area where they were born and are likely to have many close relatives nearby. Older females, then, are likely to have the largest number of relatives.

The biologist W. D. Hamilton expressed the idea of “kin selection,” that one individual assisting another could compensate for its own decrease in fitness if it helped a close relative in a way that increased the relative’s fitness. After all, he realized, the recipient of the aid is likely to have at least some genes in common with the altruistic individual. And the more genes they share (i.e., the more closely the individuals are related), the more likely it is that the alleles passed down by the recipient of the altruistic-

Thus, altruistic-

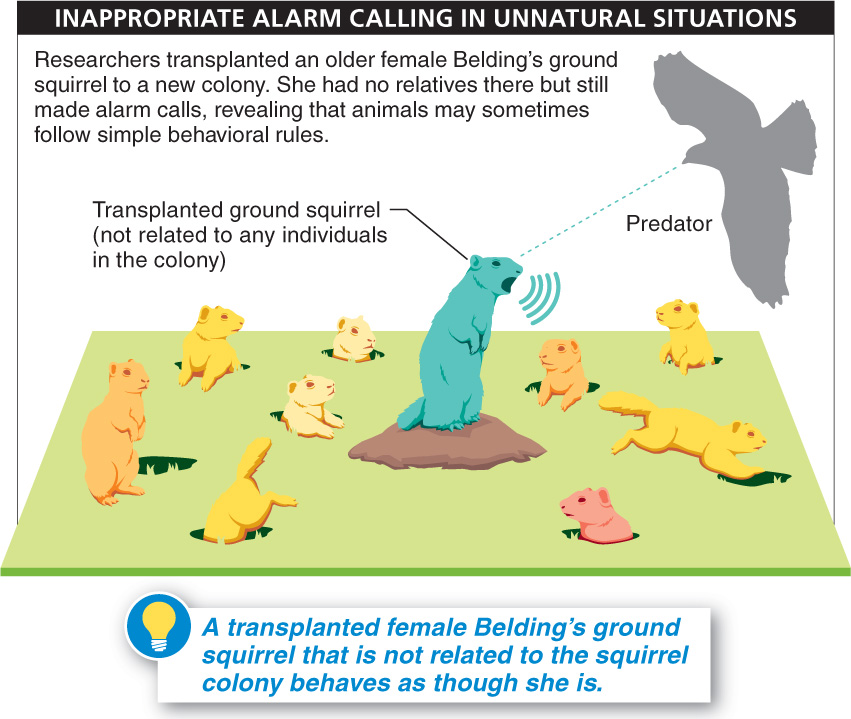

Belding’s ground squirrels probably don’t know exactly how closely they are related to the squirrels around them, so it is likely that natural selection has led to an evolutionary shortcut that allows them to behave as if they did know. In a clever experiment that tested this idea, researchers trapped adult female squirrels and relocated them to distant ground squirrel colonies in which they had no close relatives. If the transplanted females were able to determine exactly how closely they were related to the squirrels around them, they would not make alarm calls. To do so would put the caller at risk without benefiting her genes. What the researchers found, though, was that transplanted females were just as likely to sound the alarm in the colony of strangers as they were in their home territories, surrounded by close relatives (FIGURE 9-10). It seems that female ground squirrels have evolved to follow a simple rule that says, “If I am an older female, I behave as if I have many close relatives around me.”

Based on the idea of kin selection, it is necessary to redefine an individual’s fitness. An individual’s fitness is not measured just by his or her total reproductive output. Fitness also includes the reproductive output that individuals bring about through their seemingly altruistic behaviors toward their close kin. This redefined measure of fitness is called inclusive fitness.

376

No two individuals—

Q

Question 9.4

James Joyce wrote: “Whatever else is unsure in this stinking dunghill of a world, a mother’s love is not.” According to the concept of kin selection, he may not be completely right. Why?

A mother’s and a fetus’s interests differ when it comes to the question of how much food—

Now consider the fetus’s “point of view.” Future siblings will carry some but not all of the same genes as the fetus. Put another way, a fetus is always more closely related to itself than to its siblings. Consequently, the fetus does not necessarily benefit from sacrificing nutritional intake for the sake of future siblings. In a sense, it is a sibling rivalry that starts before the sibling is even conceived! The conflict results in a physiological battle throughout pregnancy. The fetus produces chemicals that increase the diameter of the mother’s blood vessels, thus increasing the amount of sugar delivered to the fetus. In response, the mother produces more insulin, a chemical that has exactly the opposite effect, reducing the amount of sugar in the bloodstream that is available to the fetus. In some mothers this conflict causes gestational diabetes, the pregnant woman’s inability to properly regulate her blood sugar levels—

377

Gestational diabetes might also be the result of conflict between the fetus’s alleles that come from its father and those that come from its mother. The parents may have different interests concerning how much to invest in the current offspring versus how much to save for future offspring (FIGURE 9-11). (Paternally inherited genes may benefit from greater resource uptake by the fetus, while maternally inherited genes may benefit from reduced resource uptake.)

Just as close relatives are more likely to help each other than are strangers, the converse is also true: the less closely related two individuals are, the more likely they are to experience conflict. Male lions, for example, on taking over a pride usually kill unrelated cubs (although females defend their young aggressively), causing the females to become reproductively ready sooner than they would if they continued nursing their cubs.

The idea of kin selection gives rise to another prediction about conflict among humans. Specifically, it implies that child abuse, when it occurs, is more likely to be abuse of a child by his or her stepparent than abuse of a child by his or her biological parent. Is this the case?

Q

Question 9.5

Is a child living with one or more stepparents at greater risk of abuse than a child of the same age living with his or her biological parents?

Numerous studies across many different cultures, including an evaluation of 20,000 reports from the American Humane Association in the United States, support what has been called the “Cinderella syndrome.” These findings included, for example, an estimate that the probability that a preschooler will be abused is about 1 in 3,000 for a child living with two biological parents (with whom he or she shares considerable genetic relatedness) and 40 in 3,000 for a child living with a stepparent (with whom he or she has no genetic relatedness). This difference in risk for children living in a home with a stepparent versus those living with their biological parents remains even when socioeconomic factors are taken into account. And the same effect has been noted in multiple other cultures. It is important to note, however, that in the overwhelming majority of stepfamilies no abuse occurs.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 9.6

Kin selection is apparently-

Older female Belding’s ground squirrels will make an alarm call to warn of predators. More than half the time, the caller is killed by the predator. Why does natural selection still favor this behavior?