21.6: Blood flows out of and back to the heart in blood vessels.

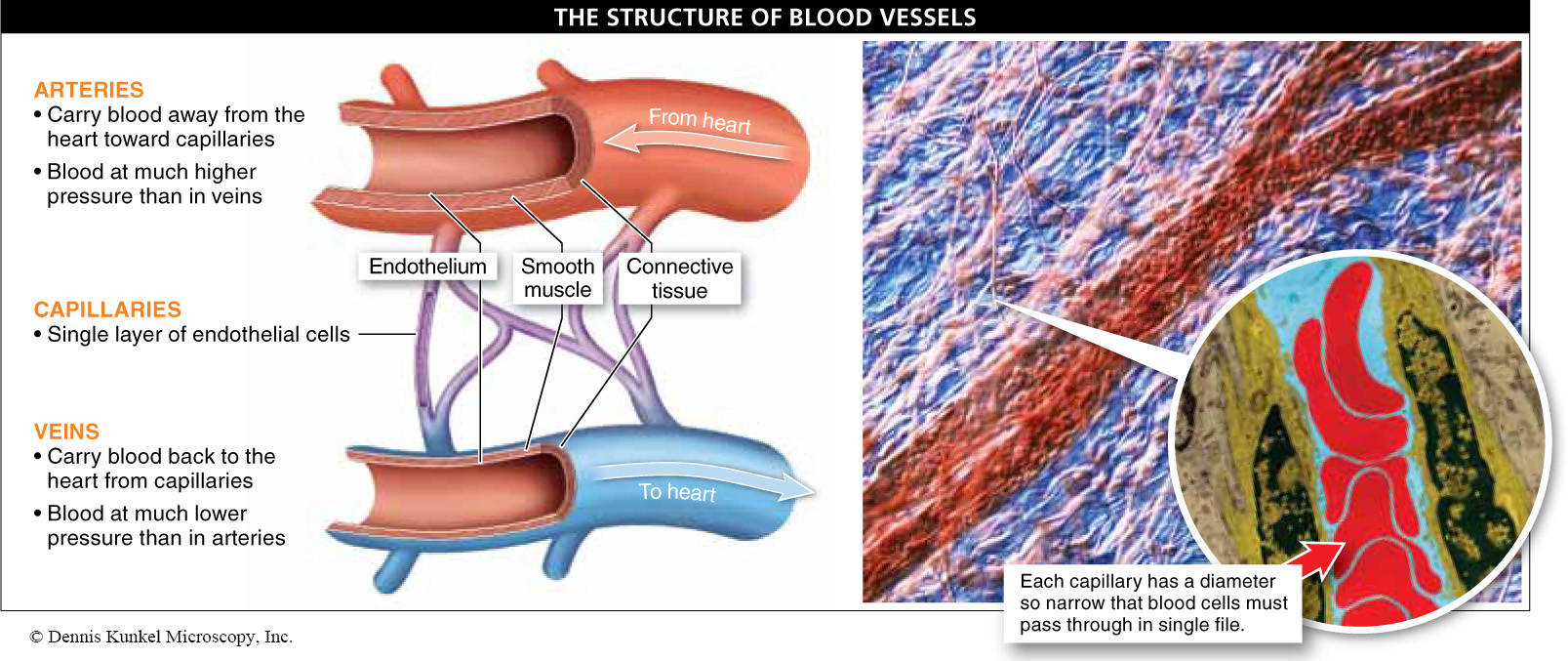

Blood flows from the heart to the tissues of the body and back to the heart again through a series of blood vessels. There are three distinct types of blood vessels: arteries, capillaries, and veins (FIGURE 21-12).

1. Arteries. Leaving the heart, blood flows through arteries. The pulmonary arteries, arising from the right ventricle, carry deoxygenated blood to the lungs. The arteries arising from the left ventricle carry oxygenated blood, first to the aorta, then to the brain and the other tissues and organs of the body.

Arteries are lined with a sheet of endothelium (a type of epithelial tissue) and surrounded by smooth muscle and a layer of connective tissue. These layers of tissue, along with collagen and other, elastic connective tissue fibers, enable arteries to stretch, accommodating the high pressure generated by each beat of the heart, and then recoil, pushing the blood forward. The thickness of the artery walls is sufficient to minimize the exchange of materials between the blood and the tissues. Arteries branch repeatedly, becoming arterioles, which become smaller and smaller in diameter as they reach into all the tissues and organs. Blood then flows from the arterioles into capillaries.

2. Capillaries. The tiniest blood vessels are the capillaries, which bring blood so close to all the cells of the body that diffusion can move the necessary molecules from the blood into the cells and from the cells into the blood. Each capillary has an inner diameter so narrow that blood cells must pass through in single file. In contrast to arteries, the walls of capillaries are thin—

Capillaries are the last branch of the circulatory system to carry nutrients to the interstitial fluid around cells, and thus into the cells. Capillaries are also the first branch to carry nutrient-

The capillaries are arranged in capillary beds, a network of vessels that supplies blood to tissues and organs. Although the diameter of capillaries is very tiny, cumulatively they have a much greater volume than the arterioles and arteries. The network of capillaries in an organism is staggeringly large—

839

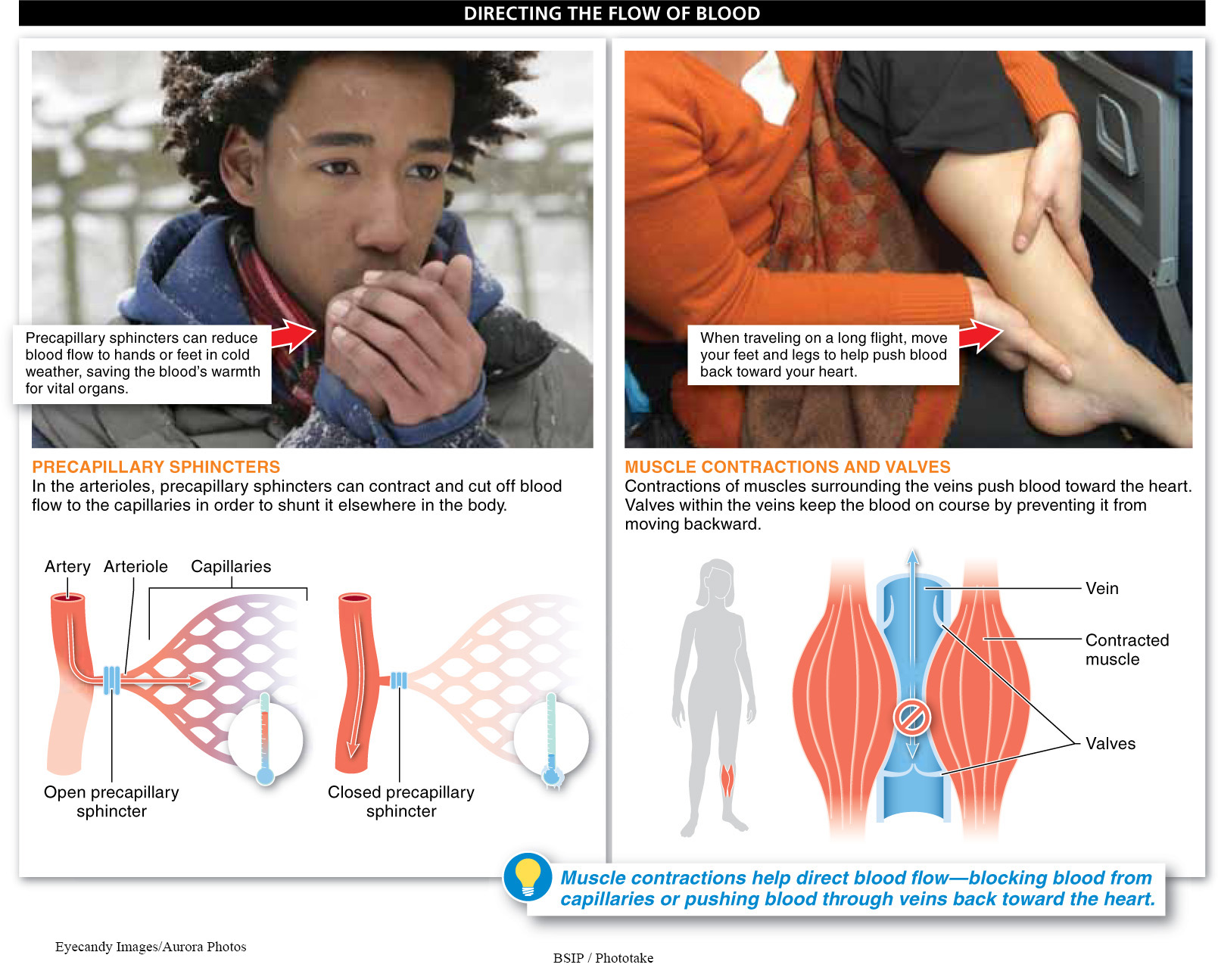

Consider this: when you go out in very cold weather, your face or hands may get very cold and may even turn bluish in color. Why does this happen? Blood flow in the capillaries is controlled by smooth muscle around the arterioles, the smaller vessels that branch off arteries and lead to capillaries. When these muscles, called precapillary sphincters, contract, blood flow can be cut off to capillaries and shunted elsewhere in the body (FIGURE 21-13). As a consequence of the activity of these muscles, bodies can reduce blood flow (and the heat it brings) to parts such as the face or hands when such blood flow could lead to excessive and energetically wasteful heat loss. (Simultaneously, these muscles enable the body to always direct blood to critical parts of the body, including the brain, heart, liver, and kidneys.) Blushing is the opposite situation: precapillary sphincters relax and blood flow to the face and neck increases.

840

“Food coma,” that feeling of lethargy following a large meal, results from a similar shunting of blood. In this case, more blood is allowed to flow through the capillaries surrounding the digestive tract, while less flows to other parts of the body. Alternatively, during strenuous exercise, more blood is directed toward the skeletal muscles in use. This accounts for the feeling of being “pumped up” during and shortly after a weightlifting session.

Q

Question 21.3

What is “food coma”?

3. Veins. Once blood has passed through the capillaries, it flows back to the heart through veins. Veins have a structure similar to that of arteries: they are lined with a sheet of endothelium and surrounded by smooth muscle and a layer of connective tissue. The layer of smooth muscle surrounding veins, however, is much thinner than that surrounding arteries, making the walls of veins much more expandable. In a person at rest, as much as 60% of the total blood volume can be in his or her veins.

The pressure of blood in the veins is only about one-

Like the capillaries, veins also aid in the control of blood flow. After sitting for a very long time, such as on a long plane or car ride, you may notice that your feet become swollen and it is difficult to put your shoes back on. What is the cause of this? The answer has to do with the way blood flows back to the heart after passing through capillary beds. Remember that capillaries, with their small diameter and thin, leaky walls, reduce the pressure and speed of flowing blood. By the time it begins collecting in veins, blood has very little pressure. It is able to “limp” back to the heart only with the assistance of two important features.

First, as muscles surrounding veins contract and relax during normal movement, they squeeze the veins, pushing the blood through. And second, within veins, at regular intervals, are one-

Regulating blood flow by means of valves in the veins and the contractions of muscles surrounding the veins usually works fine. As we’ve noted, though, you can encounter a problem if you sit for several hours. Blood pumped to your feet must somehow climb up your legs, yet in the absence of contractions of your calf and thigh muscles, this doesn’t occur so well. Instead, the blood pools in your feet, causing them to get more swollen and increasing the risk of blood clots. This is why it is good to get up and move around occasionally, or to exercise your leg muscles as you sit.

One serious circulatory problem is called varicose veins, a painful condition that occurs when the valves preventing backflow of blood malfunction and blood pools in the veins, stretching them. This can be caused or exacerbated by standing for long periods of time. Several methods are effective for treating varicose veins, including laser surgery or injections that cause the veins to slowly fade and disappear, with deeper veins taking over the circulation in that region.

Q

Question 21.4

Some individuals develop a painful condition called varicose veins—

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 21.6

Blood flows from the heart to the tissues of the body and back to the heart through a series of endothelium-

When blood returns to the heart in veins, it is at very low pressure. What two important features help blood “limp” back to the heart?

841