22.3 Calories count: organisms need sufficient energy.

Have you ever gone a whole day without eating? Or have you ever spent a few weeks trying to reduce your caloric intake? Living in a state of hunger can be torturous. In the early 1990s, eight human “guinea pigs” learned this the hard way. Living in the Biosphere 2 dome—

So how much energy do we actually need to survive? The energetic value of food is measured in very small units called calories, with a single calorie defined as the energy required to raise the temperature of 1 gram of water by 1° C. However, the term can be a bit confusing: in discussing human consumption, the term “calorie” actually refers to a kilocalorie (kcal), which is 1,000 calories. So when the label on a package of cookies says that a cookie provides “100 calories,” the cookie actually provides 100 kilocalories or 100,000 calories.

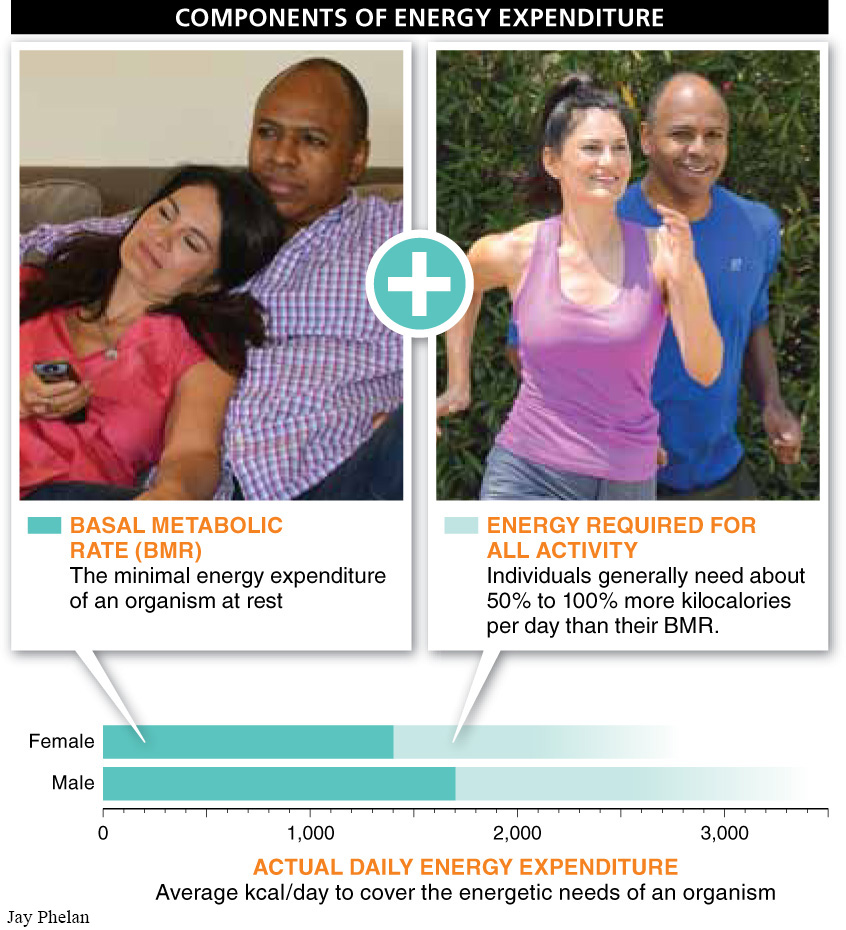

Once you have a unit of energy at hand, you can reasonably estimate how many kilocalories an individual expends each day. To establish an energy baseline, we consider an individual who is doing nothing more than the equivalent of sitting on a couch all day. This is called the basal metabolic rate, or BMR, and refers to the amount of energy expended at rest, with no food in the digestive tract, in a neutral-

877

The BMR allows easy comparisons across species because it is so clearly defined, but to accurately evaluate organisms’ energy needs, we must have a sense of how active they are. Someone moving around and involved in physical exertion will require more energy than someone sitting at a desk all day, and a very large person will require more than a small person (FIGURE 22-4). In actuality, individuals need about 50% to 100% more kilocalories per day than their BMR. A 120-

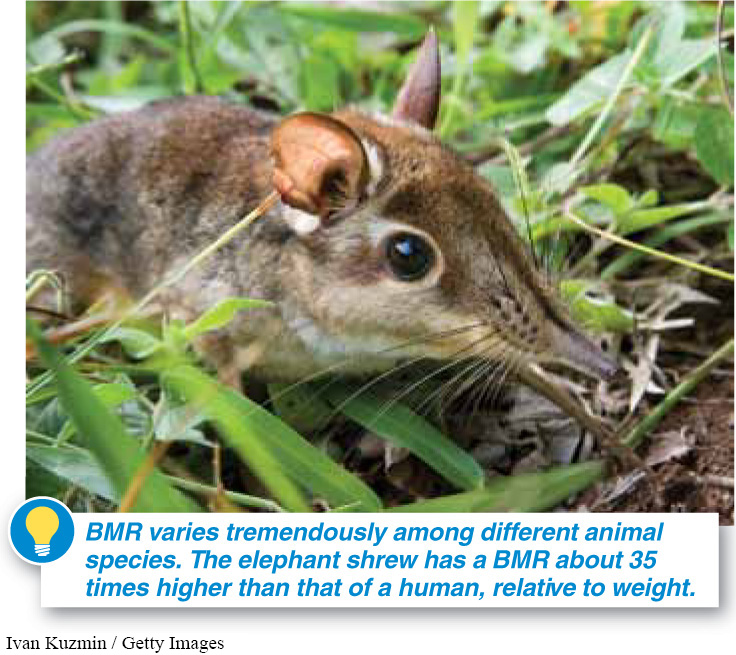

From one animal species to another, basal metabolic rates differ tremendously. For the tiny shrew, for instance, BMR is about 35 times higher than that of a human (FIGURE 22-5). The shrew’s heart beats more than 500 times per minute at rest!

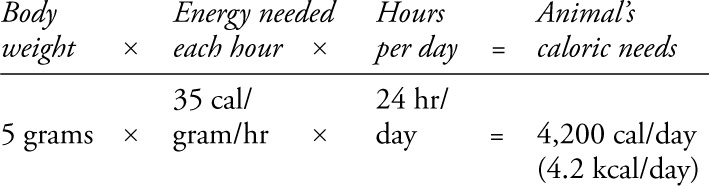

Let’s estimate what a shrew needs to eat each day. If it weighs 5 grams and has a BMR of 35 calories per hour per gram, we can calculate as follows:

Thus, the shrew would need 4.2 kcal/day if it were at rest. But if it needed another 4 kcal/day for its normal activities, it would have to eat about 8 kcal/day. As we’ll see below, a pure source of carbohydrate or protein carries about 4 kcal/gram. Thus, every day, the shrew must find and consume at least 2 grams of food. This is no small challenge when you weigh only 5 grams. The task is equivalent to a 200-

The shrew is not the only species with extreme caloric needs. Animals that fast or hibernate for long periods of time must prepare by consuming many kilocalories. Male elephant seals, for example, eat little or nothing during their 100-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 22.3

To function well, living organisms need sufficient energy, measured in kilocalories. The minimal energy needed by an individual not engaged in any activity is called its basal metabolic rate, or BMR.

Why is an individual's BMR not an accurate measure of their actual energy requirement?

878