26.1–26.4: Your body has different ways to protect you against disease-causing invaders.

Sneezing is an effective way to spread disease-causing microorganisms.

26.1 Three lines of defense prevent and fight pathogen attacks.

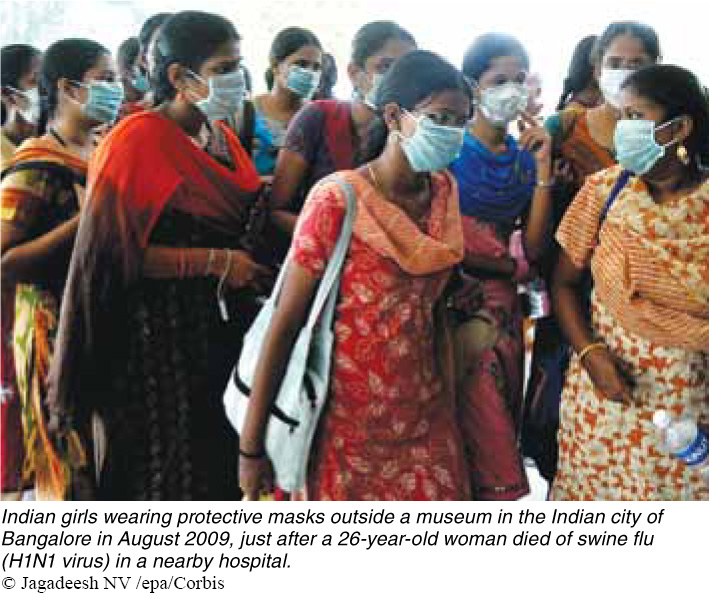

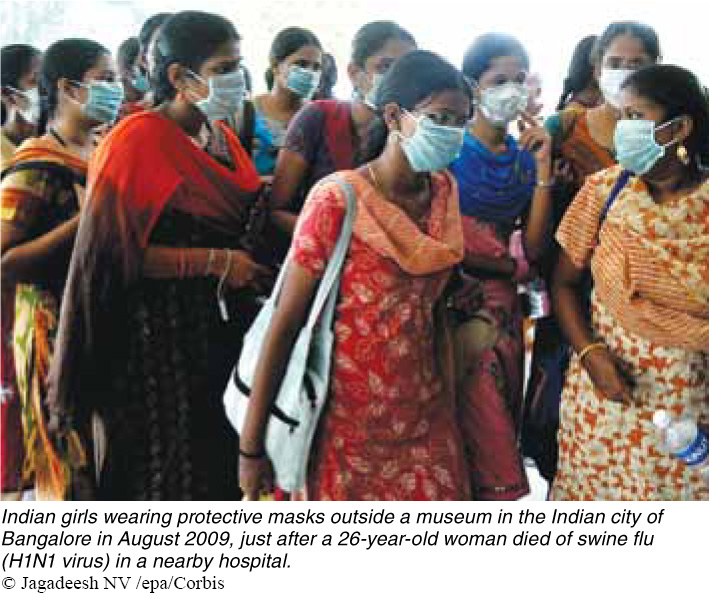

Most of us don’t think about the germs that constantly attempt to invade our bodies, until we hear that an illness is “going around.” For example, in the spring of 2009, Mexico alerted the world to an outbreak of the H1N1 virus that caused numerous deaths—particularly among people under 25 years old and pregnant women. This outbreak was caused by a new strain of the influenza virus that the world’s current population had never before encountered. The media showed footage of Mexico City residents wearing face masks and reported that schools and businesses were closing for extended periods of time. Within weeks, the virus had spread to the United States and around the world. Fortunately, as the flu strain began infecting people worldwide, researchers noted that although this influenza strain was strong, it was not as virulent as first suggested (FIGURE 26-1).

Figure 26.1: Outbreak.

Figure 26.2: Everyday encounters with pathogens. Shopping cart handles harbor germs.

Unfortunately, as the risk of one illness recedes, the risk of another often increases. In 2014, for example, there has been an outbreak of Ebola in West Africa that has spread rapidly. Caused by the Ebola virus, which is transmitted through direct contact—through broken skin or mucous membranes—the disease initially manifests as flu-like symptoms, including fever, headache, and muscle and abdominal pain. With a rapid and strong immune response, a person may recover. But often, an infection becomes severe rapidly, and in 60% to 90% of cases it is fatal. As of December 2014, close to 12,000 cases have been confirmed, with 6,841 deaths.

For influenza, when you first hear about an outbreak of a particularly dangerous type, do you think about washing your hands more frequently, wearing a face mask, and staying away from people who are coughing? These are reasonable responses—influenza can be transmitted more easily than Ebola, including by inhaling airborne viruses or touching contaminated surfaces. The H1N1 flu example demonstrates that when we are aware of pathogens, disease-causing microorganisms, molecules, and viruses (sometimes referred to as “germs”), in our environment, we may take precautions to avoid them.

Think about the commonplace items that we all touch. Did you know that shopping cart handles rank as one of the “germiest” items around? A 2006 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that for infants, riding in a shopping cart of a market that sells meat was one of the biggest risk factors for Salmonella infection (just below exposure to reptiles and eating partially cooked eggs)! Following up on this report, a 2010 study reported that 72% of the shopping carts the researchers sampled (across four states) tested positive for fecal bacteria, and the average contamination levels exceeded those measured on toilet seats and flush handles in public restrooms (FIGURE 26-2). Not surprisingly, many stores now offer disinfectant wipes, and some states have even proposed legislation to make providing these wipes mandatory.

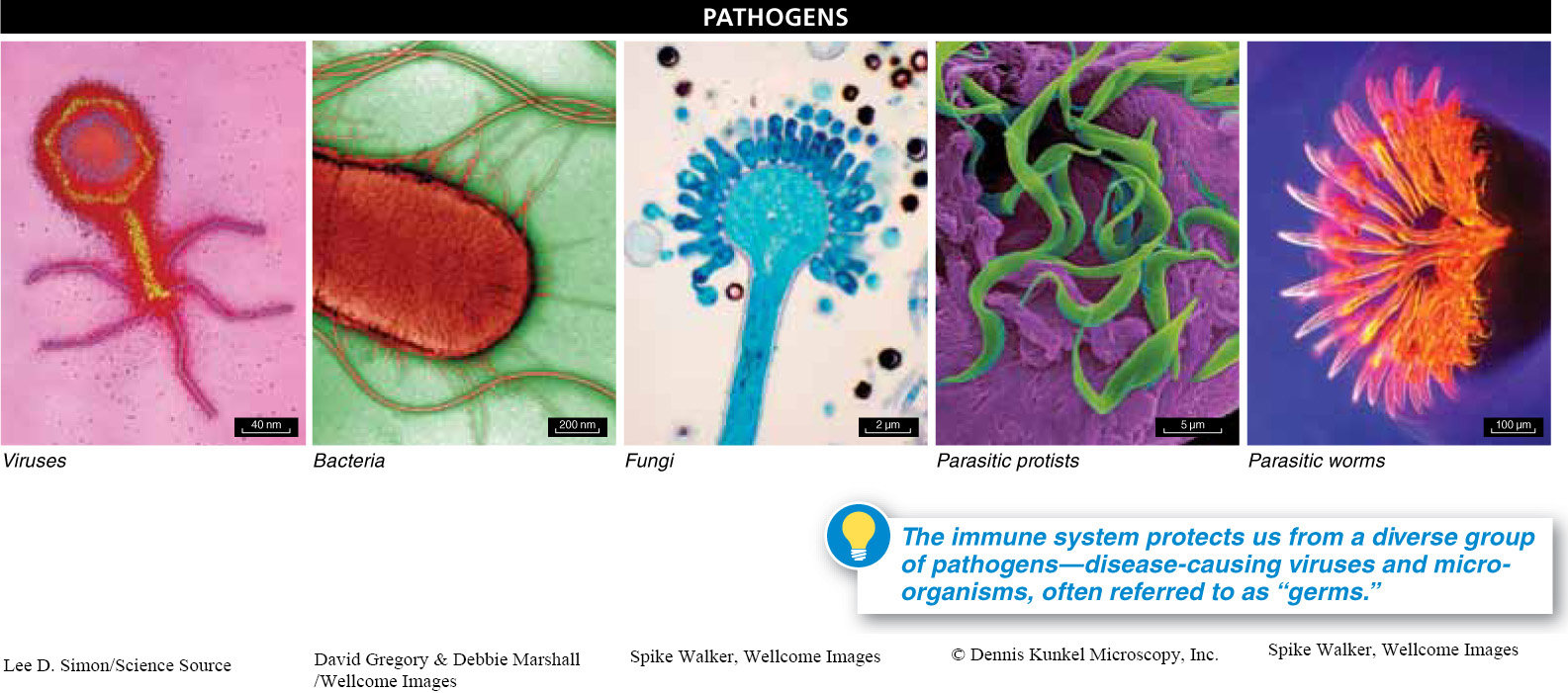

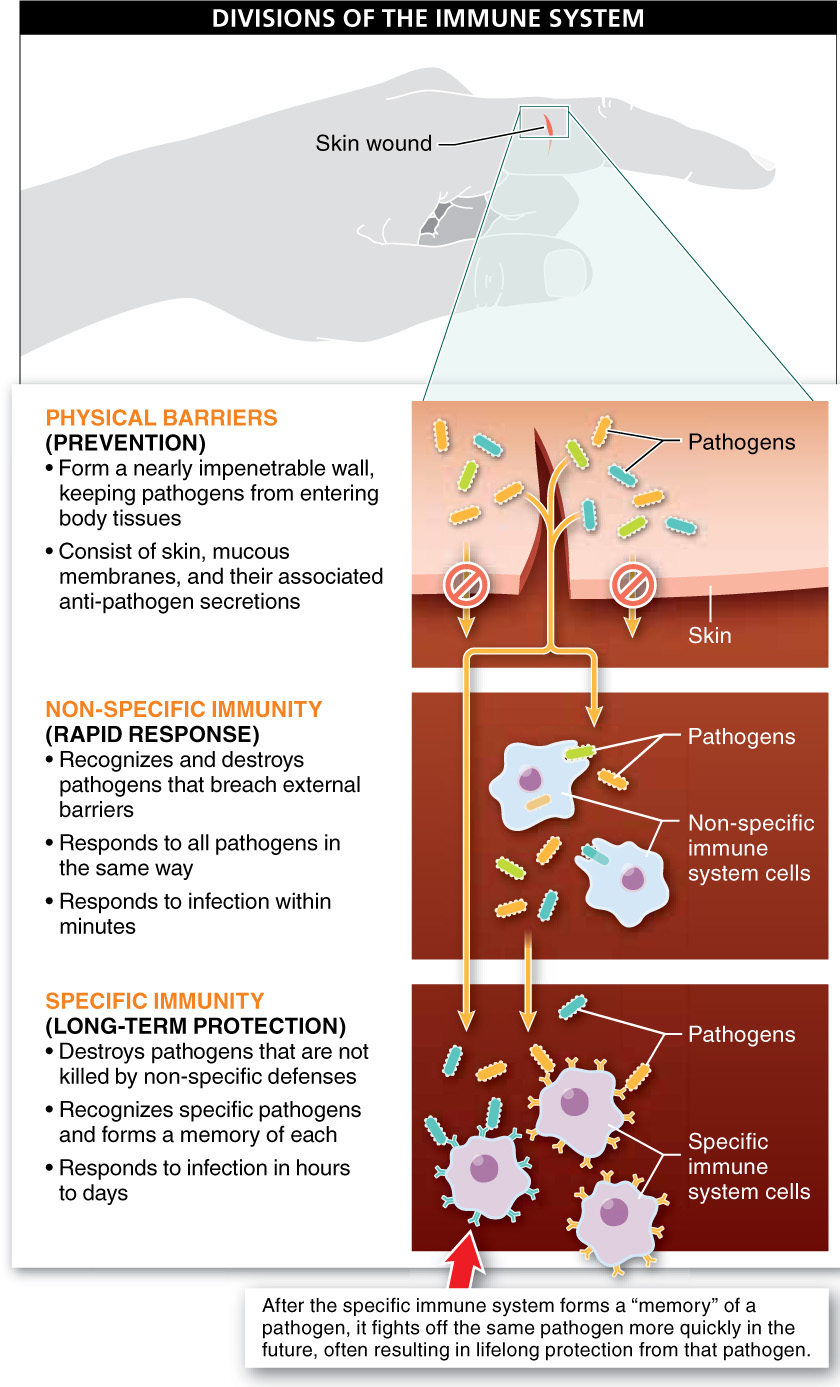

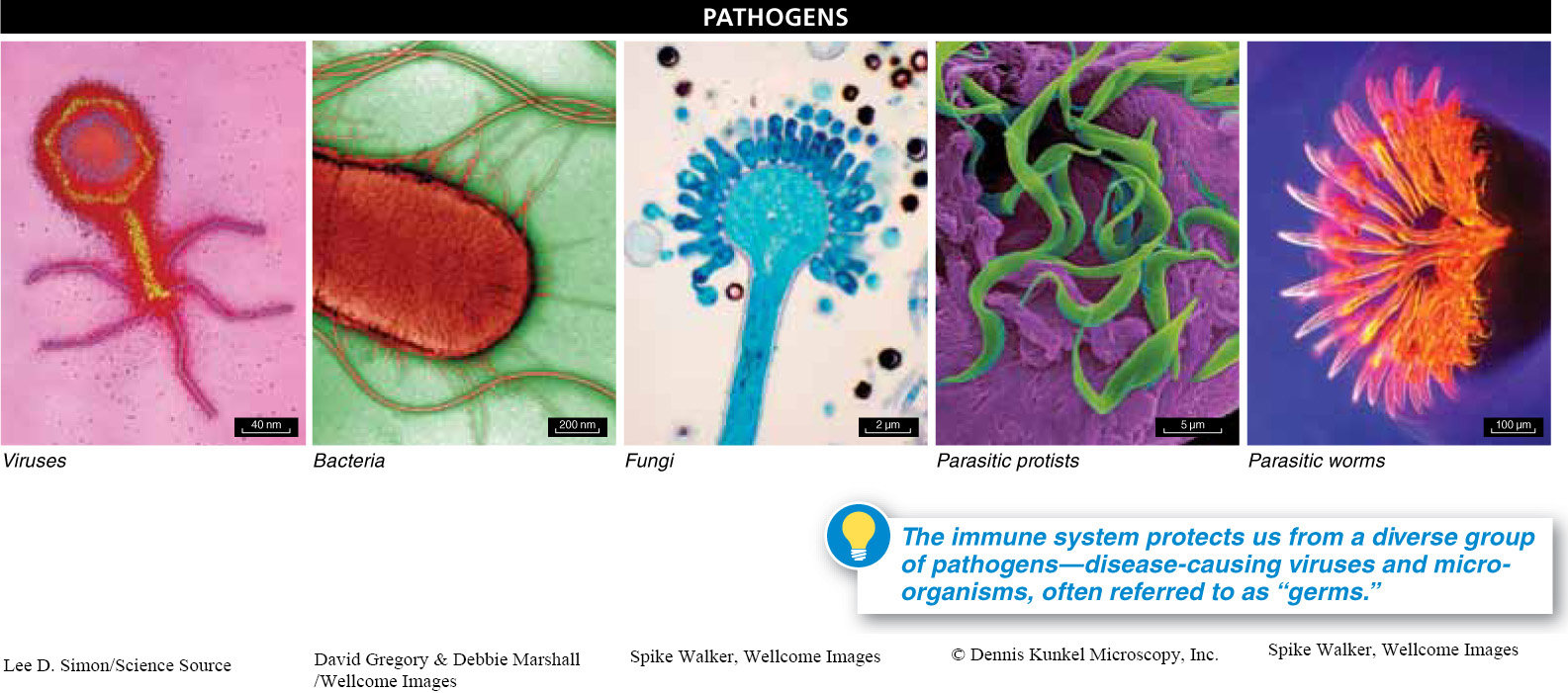

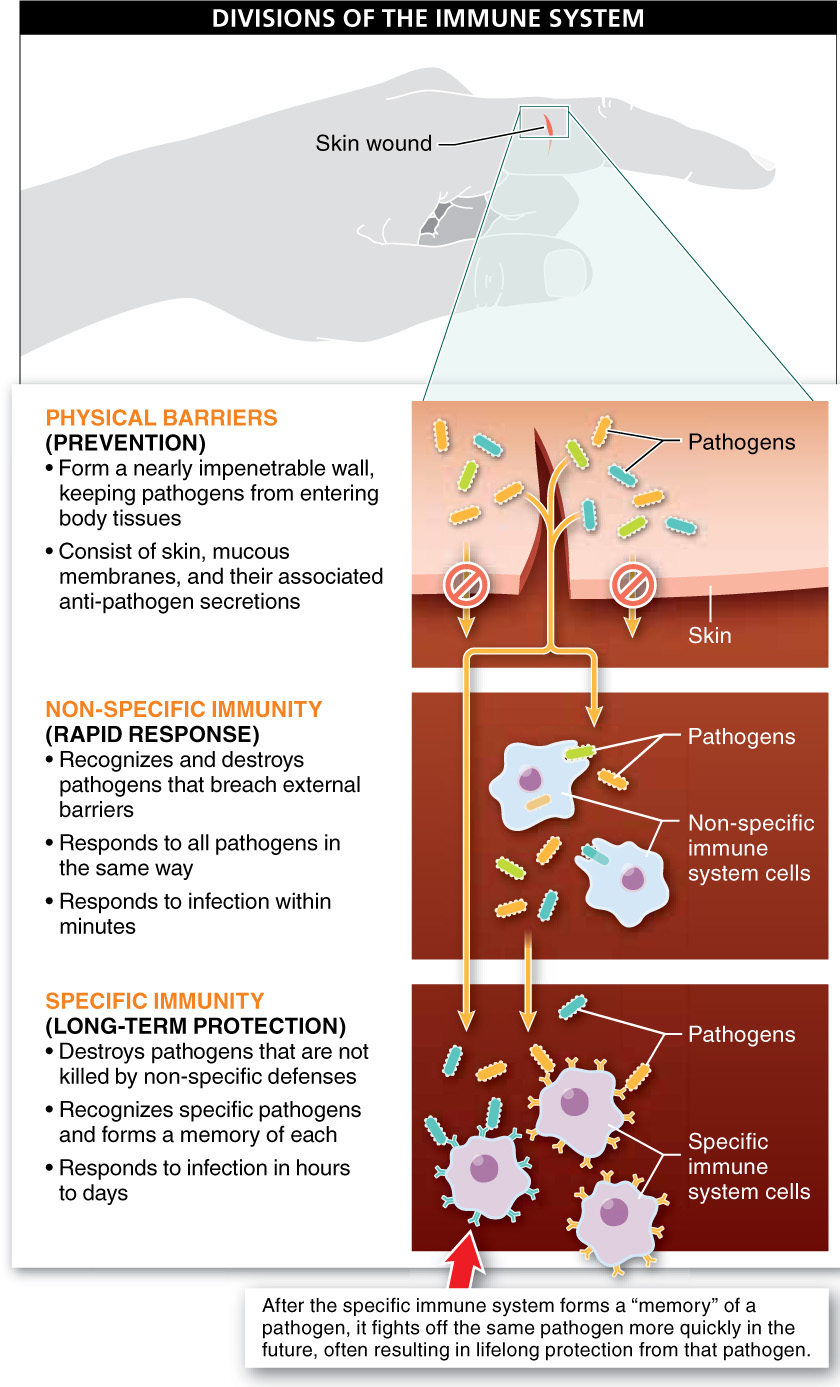

The vast majority of microscopic organisms found on everyday items will not cause disease, but some will. Our highly effective immune system sorts out benign from disease-causing microorganisms and provides protection against an enormous variety of pathogens, including many bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasitic protists and worms (FIGURE 26-3). To protect the body from pathogens, the immune system must be able to rapidly recognize what belongs in the body and what doesn’t, as well as distinguish among specific disease-causing microbes or viruses. Once a pathogen enters the human body, the immune system works within minutes to begin destroying it. The three major divisions of the immune system undertake this challenging task of protecting us against the diverse threats (FIGURE 26-4).

Figure 26.3: Examples of the foreign, “non-self” microbes and viruses that can harm the body.

Figure 26.4: Layered defenses of the immune system block entry and fight invaders.

1. Physical barriers provide the first defense against pathogens, keeping them out of the body. For example, skin acts as a nearly impenetrable barrier that keeps viruses, bacteria, and other pathogens from entering the body. In addition, skin surfaces and cells within mucous membranes secrete various chemicals that stop the growth of many pathogens.

2. Non-specific immunity is the part of the immune system that provides defense when pathogens make it past the physical barriers and into the body. The term “non-specific” indicates that these immune cells rapidly recognize and attack any and all pathogens that enter the body. The non-specific immune system is ready to function at birth and is sometimes called the innate system (meaning “inborn”). Non-specific immunity is found in virtually all multicellular organisms, including plants, nematode worms, fruit flies, and humans.

3. Specific immunity, also called adaptive immunity, is the division of the immune system that deals with pathogens that have been missed by the non-specific system or cannot be overcome by that system. The specific division recognizes particular infectious agents—the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus that causes common skin infections, for example, or the virus varicella-zoster that causes chicken pox. Because the specific immunity part of your immune system must first recognize a specific threat and then manufacture specific weapons to combat it, there is a time lag of a few hours to a few days between your exposure to the pathogen and the response to it. Once activated, the cells of the specific division “remember” past infections and can then fight off the same infection more quickly in the future. As a result, an individual often has lifelong protection from a pathogen that he or she has previously encountered.

Working together, the three divisions of the immune system protect us against diseases and infections. Physical barriers prevent access to the interior of the body, but if entry does occur, a pathogen encounters an immediate response in the form of the non-specific system. Then, to defeat the pathogen for the long term, chemical signals trigger the cells of the specific immune system to retain information about the infection for an efficient defensive response in the future.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 26.1

The immune system, which protects us from a diverse group of pathogens, has three basic parts: physical barriers, non-specific immunity, and specific immunity. Physical barriers and non-specific immunity are the first lines of defense, serving to distinguish a substance as a pathogen. Cells in the specific immunity line of defense recognize individual pathogens and remember them, so they can fight them more effectively in the future.

Why do some grocery stores offer customers disinfectant wipes for shopping cart handles?