26.8 Clonal selection helps in fighting infection now and later.

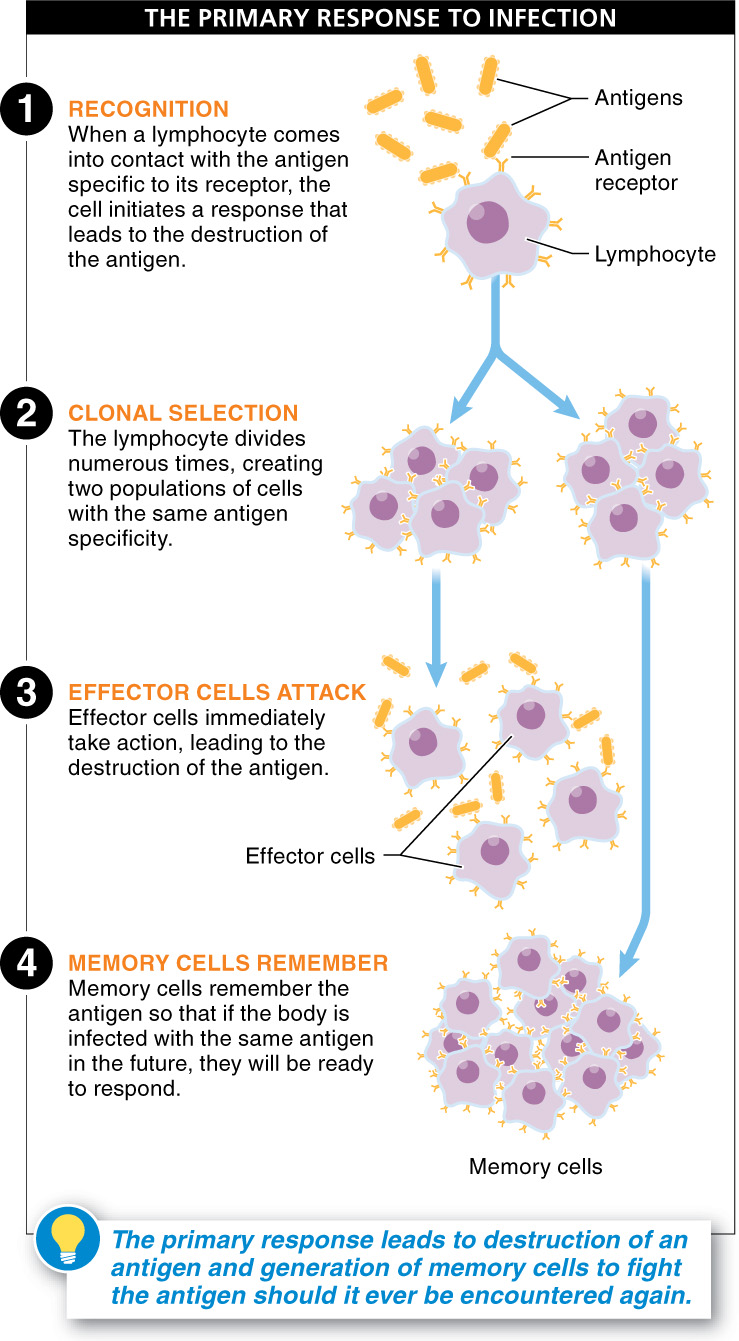

Just about every lymphocyte in an individual is unique, because of its specific antigen receptor. Although the immune system is ready to encounter any antigen, many lymphocytes will never meet the antigen they are capable of recognizing. But when a lymphocyte does come into contact with the antigen specific to its receptor, a sequence of events begins—

When a B or T cell binds to an antigen, the lymphocyte and its descendants rapidly divide numerous times to create a population of genetically identical cells (clones), all with the same antigen specificity. This process, known as clonal selection, ensures that there are enough B and T cells to recognize and respond to all of the specific pathogen that has invaded the body.

Recognizing a new pathogen is an important first step, but the specific immune system has two additional challenges: to respond to and remember the invader. Clonal selection generates many lymphocytes that can recognize the same pathogen, and these lymphocytes then function in one of two ways. Some attack the antigen (these are called the effector cells), and others are involved in creating a memory of the invasion (the memory cells). We discuss the immune system’s initial interaction with a pathogen, called the primary response, first.

The cells of the primary immune response must first be generated through clonal selection. Once generated, these lymphocyte responders, or effector cells, recognize the antigen and immediately take some action that leads to its destruction. For example, plasma cells, derived from B cells, are the effector cells in the humoral response because they secrete antibodies. And T cells that directly kill infected cells are the effector cells in the cell-

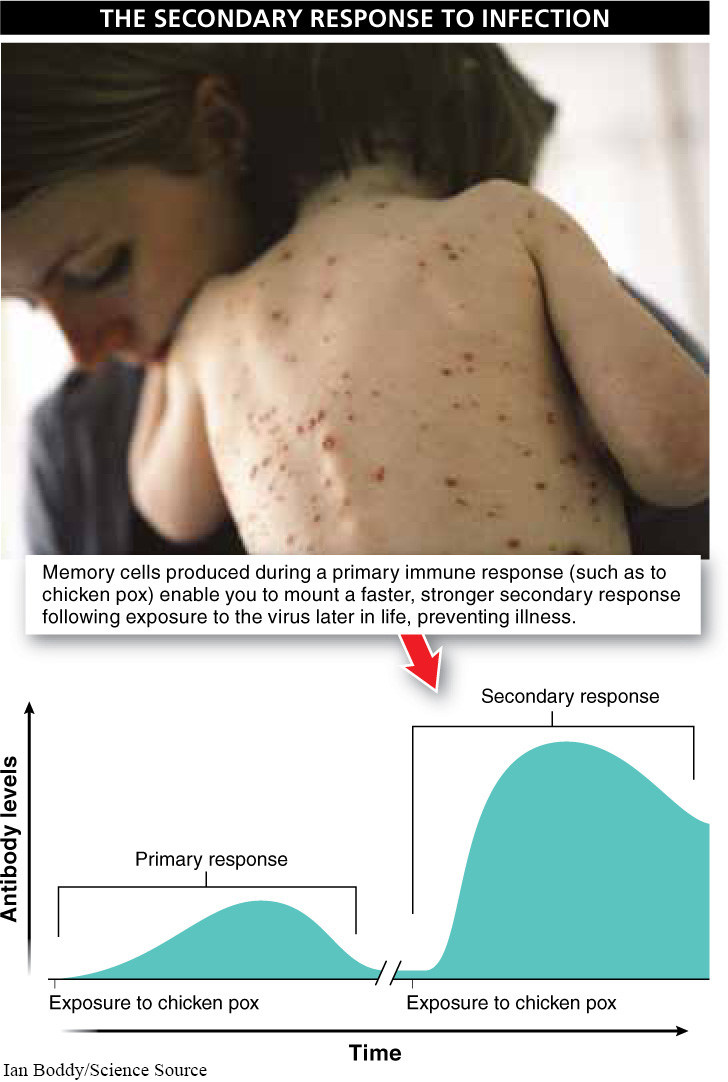

Also produced during the primary response is the second type of lymphocyte, the memory cells. Like effector cells, memory cells are produced through clonal selection. The memory cells’ job is to remember an antigen so that, if the body is infected with the same antigen in the future, it will be ready to attack the invader relatively quickly (in a matter of a couple of days rather than two weeks). Thus, memory cells remain in the lymph and blood and wait for the return of their specific antigen. There are both B and T memory cells, and they have the same antigen specificity as the effector cells produced in the primary response. While effector cells live less than a week, memory cells remain and circulate for a long time. The lifespan of memory cells is variable, but they may exist for years and possibly even for the individual’s lifetime.

1064

With this understanding of how effector cells and memory cells act in the primary immune response, let’s look at what happens when a five-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 26.8

When the body encounters a specific antigen, the lymphocytes recognizing this antigen divide to produce many identical cells through clonal selection. During a primary response, effector cells respond to and attack the antigen. Memory cells produced during the primary response are ready to go through clonal selection if a secondary response is necessary.

How does the body's primary response to a particular pathogen differ from the body's secondary response to the same pathogen?

1065