9.11: Males and females are vulnerable at different stages of the reproductive exchange.

Suppose you are on your college campus and a person of the opposite sex comes up to you and says, “Hi. I have been noticing you around campus. I find you very attractive. Would you go out with me tonight?” What percentage of men would answer yes? And women? In a study conducted at Florida State University in 1978 and 1982, the percentage answering yes was 50% for both males and females.

Now imagine the question was “Would you have sex with me tonight?” Among the men, 75% said yes; among the women, not a single one said yes. It is tempting to interpret such results as a consequence solely of the culture of Western society, characterized by significant differences in the expectations and tolerances of male and female sexual conduct. However, cultural expectations don’t adequately explain the consistency of the pattern found across Western and non-

385

Studies of male-

Humans, like nearly all mammals, are characterized by a greater initial reproductive investment by females. For females, the cost of a poor mating choice can have significant consequences—

Two differences in the sexual behavior of males and females across the animal kingdom have evolved:

- 1. The sex with the greater energetic investment in reproduction is more discriminating about mating.

- 2. Members of the sex with the lower energetic investment in reproduction compete among themselves for access to the higher-

investing sex.

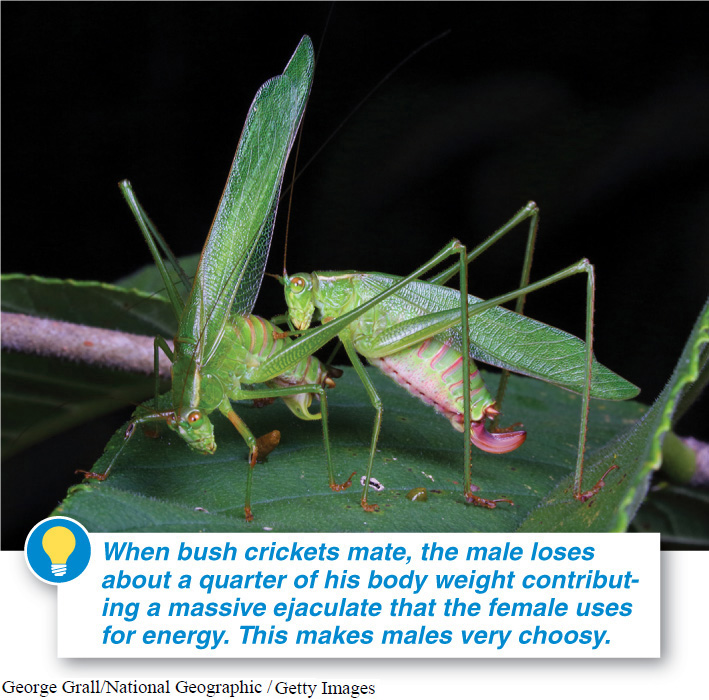

A dramatic illustration of how a high reproductive investment leads to the evolution of choosiness in mating behavior comes from the insect world. When bush crickets mate, the male loses about a quarter of its body weight in contributing a massive ejaculate (the equivalent of nearly 50 pounds of semen in a human), which the female then uses for energy (FIGURE 9-20). It can represent up to one-

386

Not surprisingly, male crickets are very choosy when selecting a mate. They reject small females that would produce relatively few offspring. Females, you won’t be surprised to learn, spend a great deal of effort courting males.

The sex with the greater reproductive investment must be choosy: a poor choice of mate could be disastrous. The sex with the lower initial reproductive investment (usually males), on the other hand, is not made vulnerable through its mating choices, because the matings are of little energetic consequence.

The point of greatest vulnerability for males comes when they provide parental care to offspring. Due to paternity uncertainty, there is some chance that the male may be investing in offspring that are not his own. This has significant evolutionary costs: rather than increasing his own fitness, he is increasing the fitness of another male. Females, conversely, are less vulnerable at the point of providing parental care, because a female can be completely certain that the offspring she gives birth to are her own.

In the next two sections, we explore the evolution of reproductive behaviors that help males and females reduce their vulnerability and maximize their reproductive success. As we explore some general patterns of reproductive behavior among males and females, it is important to keep two critical points in mind.

1. There is tremendous variability across species in male and female behaviors. For example, the use of DNA fingerprinting to identify the parents of bird offspring has led to some surprising revelations. In significantly more cases than researchers originally predicted, offspring have different fathers than observers assumed. It seems that things are not always as they appear to observing biologists. As a consequence, much of the new research calls into question some long-

2. Throughout history, there have been many cases of people using observations and scientific findings to justify a wide variety of discriminatory thoughts and behaviors—

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 9.11

Differing patterns of investment in reproduction make males and females vulnerable at different stages of the reproductive process. This has contributed to the evolution of differences in their sexual behavior. The sex with greater energetic investment in reproduction is more discriminating about mates, and members of the sex with a lower energetic investment in reproduction compete among themselves for access to the higher-

Briefly describe the two differences that have evolved in the sexual behavior of males and females.