Albinism in the Hopis

1

Rising a thousand feet above the desert floor, Black Mesa dominates the horizon of the Enchanted Desert and provides a familiar landmark for travelers passing through northeastern Arizona. Not only is Black Mesa a prominent geological feature, but, more significantly, it is the ancestral home of the Hopi Native Americans. Fingers of the mesa reach out into the desert, and alongside or on top of each finger is a Hopi village. Most of the villages are quite small, having only a few dozen inhabitants, but they are incredibly old. One village, Oraibi, has existed on Black Mesa since 1150 a.d. and is the oldest continuously occupied settlement in North America.

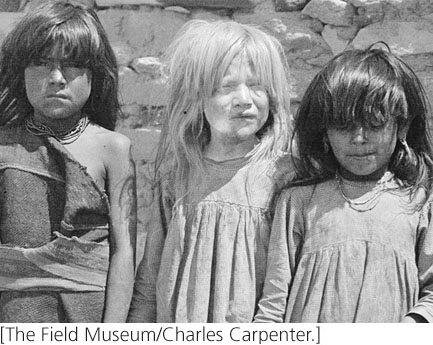

In 1900, Alěs Hrdliěka, an anthropologist and physician working for the American Museum of Natural History, visited the Hopi villages of Black Mesa and reported a startling discovery. Among the Hopis were 11 white persons—not Caucasians, but actually white Hopi Native Americans. These persons had a genetic condition known as albinism (Figure 1.1).

Albinism is caused by a defect in one of the enzymes required to produce melanin, the pigment that darkens our skin, hair, and eyes. People with albinism either don’t produce melanin or produce only small amounts of it and, consequently, have white hair, light skin, and no pigment in the irises of their eyes. Melanin normally protects the DNA of skin cells from the damaging effects of ultraviolet radiation in sunlight, and melanin’s presence in the developing eye is essential for proper eyesight.

The genetic basis of albinism was first described by the English physician Archibald Garrod, who recognized in 1908 that the condition was inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, meaning that a person must receive two copies of an albino mutation—one from each parent—to have albinism. In recent years, the molecular natures of the mutations that lead to albinism have been elucidated. Albinism in humans is caused by defects in any one of several different genes that control the synthesis and storage of melanin; many different types of mutations can occur at each gene, any one of which may lead to albinism. The form of albinism found in the Hopis is most likely oculocutaneous albinism (albinism affecting the eyes and skin) type II, due to a defect in the OCA2 gene on chromosome 15.

The Hopis are not unique in having albinos among the members of their tribe. Albinism is found in almost all human ethnic groups and is described in ancient writings; it has probably been present since humankind’s beginnings. What is unique about the Hopis is the high frequency of albinism in their population. In most human groups, albinism is rare, present in only about 1 in 20,000 persons. In the villages on Black Mesa, it reaches a frequency of 1 in 200, a hundred times as frequent as in most other populations.

2

Why is albinism so frequent among the Hopis? The answer to this question is not completely known, but geneticists who have studied albinism in the Hopis speculate that the high frequency of the albino gene is related to the special place that albinism occupied in the Hopi culture. For much of their history, the Hopis considered members of their tribe with albinism to be important and special. People with albinism were considered pretty, clean, and intelligent. Having a number of people with albinism in one’s village was considered a good sign, a symbol that the people of the village contained particularly pure Hopi blood. Albinos performed in Hopi ceremonies and held positions of leadership within the tribe, often as chiefs, healers, and religious leaders.

Hopi albinos were also given special treatment in everyday activities. The Hopis have farmed small garden plots at the foot of Black Mesa for centuries. Every day throughout the growing season, the men of the tribe trekked to the base of Black Mesa and spent much of the day in the bright southwestern sunlight tending their corn and vegetables. With little or no melanin pigment in their skin, people with albinism are extremely susceptible to sunburn and have increased incidences of skin cancer when exposed to the sun. Furthermore, many don’t see well in bright sunlight. Therefore, the male Hopis with albinism were excused from this normal male labor and allowed to remain behind in the village with the women of the tribe, performing other duties.

Throughout the growing season, the albino men were the only male members of the tribe in the village with the women during the day and, thus, they enjoyed a mating advantage, which helped to spread their albino genes. In addition, the special considerations given to albino Hopis allowed them to avoid the detrimental effects of albinism—increased skin cancer and poor eyesight. The small size of the Hopi tribe probably also played a role by allowing chance to increase the frequency of the albino gene. Regardless of the factors that led to the high frequency of albinism, the Hopis clearly respected and valued the members of their tribe who possessed this particular trait. Unfortunately, people with genetic conditions in many societies are often subject to discrimination and prejudice.  TRY PROBLEMS 1 AND 25

TRY PROBLEMS 1 AND 25

Genetics is one of the most rapidly advancing fields of science, with important new discoveries reported every month. Look at almost any major newspaper or news magazine and chances are that you will see articles related to genetics: the completion of another genome, such as that of the Monarch butterfly; the discovery of genes that affect major diseases, including multiple sclerosis, depression, and cancer; a report of DNA analyzed from long-extinct animals such as the woolly mammoth; and the identification of genes that affect skin pigmentation, height, and learning ability in humans. Even among advertisements, you are likely to see ads for genetic testing to determine a person’s ancestry, paternity, and susceptibility to diseases and disorders. These new findings and applications of genetics often have significant economic and ethical implications, making the study of genetics relevant, timely, and interesting.

This chapter introduces you to genetics and reviews some concepts that you may have encountered briefly in a biology course. We begin by considering the importance of genetics to each of us, to society at large, and to students of biology. We then turn to the history of genetics, how the field as a whole developed. The final part of the chapter presents some fundamental terms and principles of genetics that are used throughout the book.