7.3 Viruses Are Simple Replicating Systems Amenable to Genetic Analysis

All organisms—

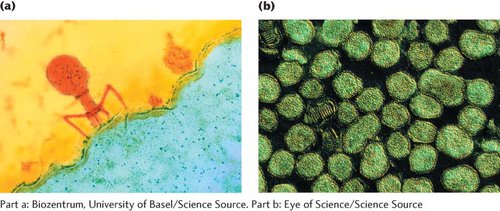

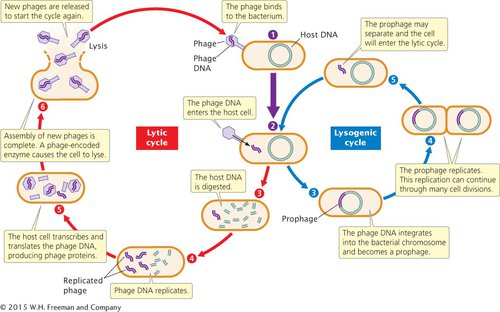

Viruses that infect bacteria (bacteriophages, or phages) have played a central role in genetic research since the late 1940s. They are ideal for many types of genetic research because they have small and easily manageable genomes, reproduce rapidly, and produce large numbers of progeny. Bacteriophages have two alternative life cycles: the lytic and the lysogenic cycles. In the lytic cycle, a phage attaches to a receptor on the bacterial cell wall and injects its DNA into the cell (Figure 7.20). Inside the host cell, the phage DNA is replicated, transcribed, and translated, producing more phage DNA and phage proteins. New phage particles are assembled from these components. The phages then produce an enzyme that breaks open the host cell, releasing the new phages. Virulent phages reproduce strictly through the lytic cycle and kill their host cells.

Temperate phages can undergo either the lytic or the lysogenic cycle. The lysogenic cycle begins like the lytic cycle (see Figure 7.20), but inside the cell, the phage DNA integrates into the bacterial chromosome, where it remains as an inactive prophage. The prophage is replicated along with the bacterial DNA and is passed on when the bacterium divides. Certain stimuli can cause the prophage to dissociate from the bacterial chromosome and enter the lytic cycle, producing new phage particles and lysing the cell.