Construct Sound Arguments

Printed Page 195

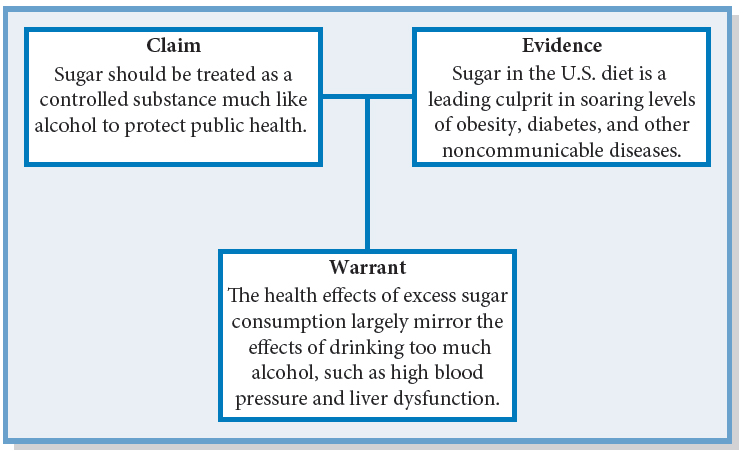

The persuasive power of any speech is based on the quality of the arguments within it. Arguments themselves are comprised of three elements: claims, evidence, and warrants.

- The claim (also called a proposition) states the speaker’s conclusion, based on evidence. The claim answers the question, “What are you trying to prove?”8

- The evidence substantiates the claim. Every key claim you make in a speech must be supported with evidence that provides grounds for belief (see Chapter 8).

- The warrant provides reasons that the evidence is valid or supports the claim. Warrants are lines of reasoning that substantiate in the audience’s mind the link between the claim and the evidence (see Figure 24.2).

Source: Robert H. Lustig, Laura A. Schmidt, and Claire D. Brindis, “Public Health: The Toxic Truth About Sugar.” Nature 482 (February 2, 2012), doi:10.1038/482027a.

Identify the Nature of Your Claims

Depending on the nature of the issue, an argument may address three different kinds of claims: of fact, of value, and of policy. Each type requires evidence to support it. A persuasive speech may contain only one type of claim or, very often, consist of several arguments addressing different kinds of claims. In a persuasive speech, a claim can serve as a main point or it can be the speech thesis (if using only one claim).

- Claims of fact focus on whether something is or is not true or whether something will or will not happen. They usually address issues for which two or more competing answers exist, or those for which an answer does not yet exist (called a speculative claim). An example of the first is, “Does affirmative action discriminate against nonminority job applicants?” An example of the second is, “Will a woman president be elected in the next U.S. presidential election?”

- Claims of value address issues of judgment. Rather than attempting to prove the truth of something, as in claims of fact, speakers arguing claims of value try to show that something is right or wrong, good or bad, worthy or unworthy. Examples include “Is assisted suicide ethical?” and “Should late-term abortions be permitted when a woman’s health is at stake?” The evidence in support of a value claim tends to be more subjective than for a fact claim.

- Claims of policy recommend that a specific course of action be taken or approved. Examples include “Full-time students who commute to campus should be granted reduced parking fees” and “Property taxes should be increased to fund classroom expansions in city elementary schools.” Notice that in each claim the word “should” appears. A claim of policy speaks to an “ought” condition, proposing that certain better outcomes would be realized if the proposed condition were met.

Checklist: Structure the Claims in Your Persuasive Speech

Checklist: Structure the Claims in Your Persuasive Speech

![]() When addressing whether something is or is not true, or whether something will or will not happen, frame your argument as a claim of fact.

When addressing whether something is or is not true, or whether something will or will not happen, frame your argument as a claim of fact.

![]() When addressing issues that rely upon individual judgment of right and wrong for their resolution, frame your argument as a claim of value.

When addressing issues that rely upon individual judgment of right and wrong for their resolution, frame your argument as a claim of value.

![]() When proposing a specific outcome or solution to an issue, frame your argument as a claim of policy.

When proposing a specific outcome or solution to an issue, frame your argument as a claim of policy.

Use Convincing Evidence

Every key claim must be supported with convincing evidence, supporting material that provides grounds for belief. Chapter 8 describes several forms of evidence: examples, narratives, testimony, facts, and statistics. These most common forms of evidence—called “external evidence” because the knowledge does not generate from the speaker’s own experience—are most powerful when they impart new information that the audience has not previously used in forming an opinion.9

You can also use the audience’s preexisting knowledge and opinions—what listeners already think and believe—as evidence for your claims. Nothing is more persuasive to listeners than a reaffirmation of their own attitudes, beliefs, and values, especially for claims of value and policy. To use this form of evidence, however, you must first identify what the audience knows and believes about the topic, and then present information that confirms these beliefs.

Finally, when the audience will find your opinions credible and convincing, consider using your own speaker expertise as evidence. Be aware, however, that few persuasive speeches can be convincingly built solely on speaker experience and knowledge. Offer your expertise in conjunction with other forms of evidence.

Address the Other Side of the Argument

A persuasive speech message can be either one- or two-sided. A one-sided message does not mention opposing claims; a two-sided message mentions opposing points of view and sometimes refutes them. Research suggests that two-sided messages generally are more persuasive than one-sided messages, as long as the speaker adequately refutes opposing claims.10

All attempts at persuasion are subject to counterargument. Listeners may be persuaded to accept your claims, but once they are exposed to opposing claims they may change their minds. If listeners are aware of opposing claims and you ignore them, you risk a loss of credibility. Yet you need not painstakingly acknowledge and refute all opposing claims. Instead, raise and refute the most important counterclaims and evidence that the audience would know about. Ethically, you can ignore counterclaims that don’t significantly weaken your argument.11

Use Effective Reasoning

Reasoning is the process of drawing conclusions from evidence. Arguments can be reasoned inductively, deductively, or causally. Arguments using deductive reasoning begin with a general principle or case, followed by a specific example of the case, which then leads to the speaker’s conclusion.

In a deductive line of argument, if you accept the general principle and the speaker’s specific example of it, you must accept the conclusion:

| GENERAL CASE (“MAJOR PREMISE”): | All men are mortal. |

| SPECIFIC CASE (“MINOR PREMISE”): | Socrates is a man. |

| CONCLUSION: | Therefore Socrates is mortal. |

Reversing direction, an argument using inductive reasoning moves from specific cases (minor premises) to a general conclusion supported by those cases. The speaker offers evidence that points to a conclusion that appears to be, but is not necessarily, true:

| SPECIFIC CASE 1: | In one five-year period, the average daily temperature (ADT) on Continent X rose three degrees. |

| SPECIFIC CASE 2: | In that same period, ADT on Continent Y rose three degrees. |

| SPECIFIC CASE 3: | In that same period, ADT on Continent Z rose three degrees. |

| CONCLUSION: | Globally, average daily temperatures appear to be rising by three degrees. |

Arguments based on inductive reasoning can be strong or weak; that is, listeners may decide the claim is probably true, largely untrue, or somewhere in between.

Reasoning by analogy is a common form of inductive reasoning. Here, the speaker compares two similar cases and implies that what is true in one case is true in the other. The assumption is that the characteristics of Case A and Case B are similar, if not the same, and that what is true for B must also be true for A.

Arguments can also follow lines of causal reasoning, in which the speaker argues that one event, circumstance, or idea (the cause) is the reason (effect) for another. For example, “Smoking causes lung cancer.” Sometimes a speaker can argue that multiple causes lead to a single effect, or that a single cause leads to multiple effects. (For more details on the cause-effect pattern, see Chapter 13.)

Avoid Fallacies in Reasoning

A logical fallacy is either a false or erroneous statement or an invalid or deceptive line of reasoning.12 In either case, you need to be aware of fallacies in order to avoid making them in your own speeches and to be able to identify them in the speeches of others. Many fallacies of reasoning exist; the following are merely a few.

| LOGICAL FALLACY | EXAMPLES |

| Begging the questionAn argument that is stated in such a way that it cannot help but be true, even though no evidence has been presented. |

|

| Bandwagoning An argument that uses (unsubstantiated) general opinion as its (false) basis. |

|

| Either-or fallacy An argument stated in terms of only two alternatives, even though there may be many additional alternatives. |

|

| Ad hominem argument An argument that targets a person instead of the issue at hand in an attempt to incite an audience’s dislike for that person. |

|

| Red herringAn argument that relies on irrelevant premises for its conclusion. |

|

| Hasty generalizationAn argument in which an isolated instance is used to make an unwarranted general conclusion. |

|

| Non sequitur (“does not follow”)An argument in which the conclusion is not connected to the reasoning. |

|

| Slippery slopeA faulty assumption that one case will lead to a series of events or actions. |

|

Appeal to traditionAn argument suggesting that audience members should agree with a claim because that is the way it has always been done. |

|