ENERGY AND NUTRIENT NEEDS DURING PREGNANCY

Typically, a pregnant woman only needs to start consuming more calories after the first trimester, because early in pregnancy, the developing fetus is comparatively small in relation to the mother’s body mass. In general, in the second and third trimesters, pregnant women need between 2,200 and 2,900 total calories a day; the exact number depends on prepregnancy weight and the mother’s activity level. Women should increase their caloric intake gradually using nutrient-

397

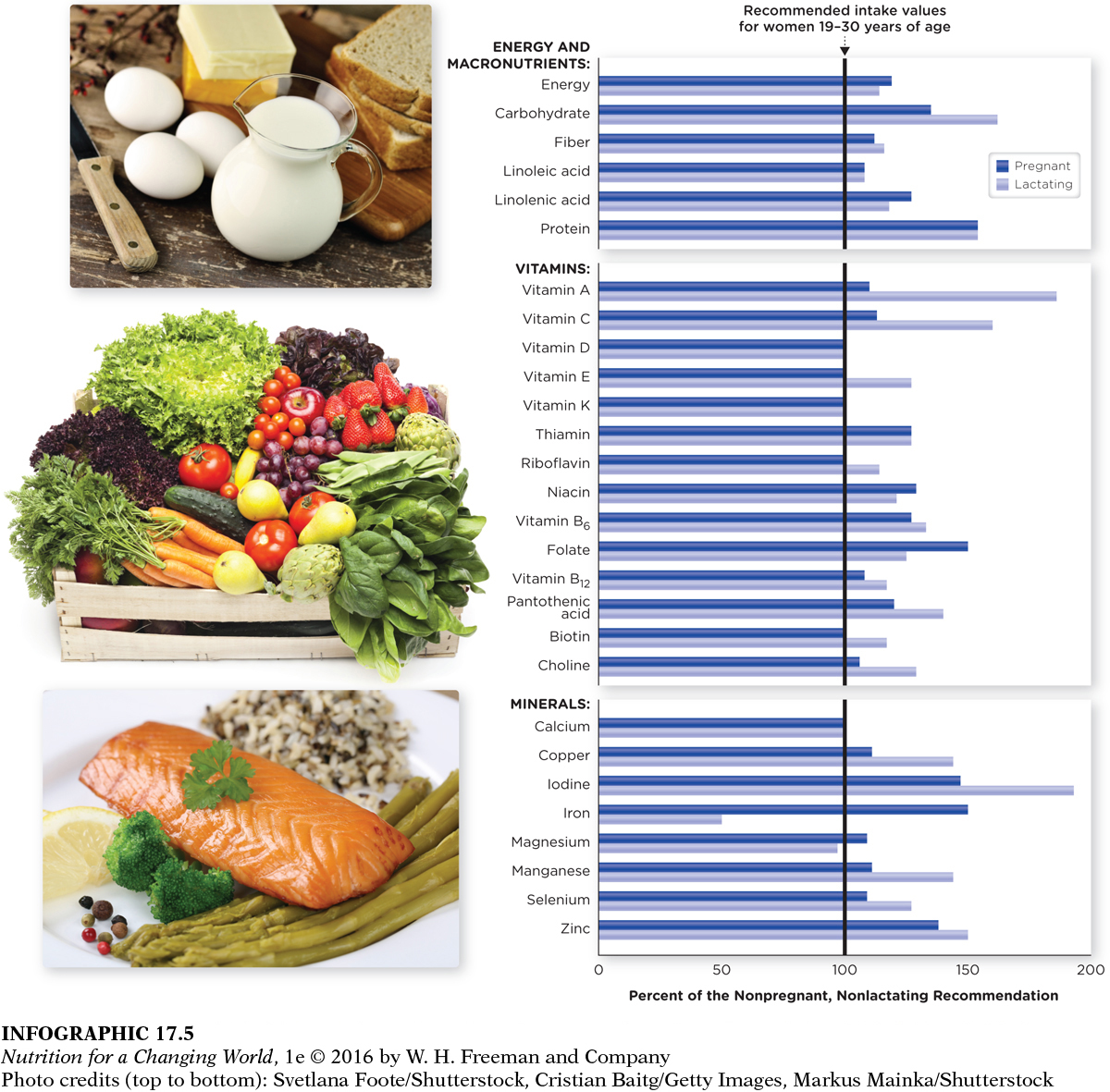

One excellent resource for pregnancy meal planning is the Health & Nutrition Information for Pregnant & Breastfeeding Women on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) ChooseMyPlate.org website, which provides a personalized daily food plan based on age, height, weight, physical activity level, and stage of pregnancy or breastfeeding status. That all said, a better gauge of appropriate intake is to monitor weight gain during pregnancy than to count daily calories. (INFOGRAPHIC 17.5)

Question 17.2

What nutrients have higher recommendations during lactation than during pregnancy?

What nutrients have higher recommendations during lactation than during pregnancy?

The nutrients that have a higher recommendation during lactation than during pregnancy are carbohydrate, fiber, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, riboflavin, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, choline, copper, iodine, manganese, selenium, and zinc.

CRITICAL PERIODS developmental events occurring during the first trimester of pregnancy in which cells differentiate and organs and vital systems begin to develop

Pregnant women need more calories to support their growing baby and they need more nutrients for themselves, too, all of which are best supplied through a wide variety of nutrient-

Nutrients needed in increased amounts

Ultimately, pregnant women need only 15% more total calories than nonpregnant women, but about 50% more of some nutrients such as protein, folate, zinc, iodine, and iron. Pregnant women can meet most of their nutritional requirements through food; in fact, the only nutrient for which a supplement is universally recommended is iron. However, prenatal multivitamin-

Folate

NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS malformation of the spine during early development

Folate (the synthetic form of which is called folic acid), a water-

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all women between the ages of 15 and 45 years—

Vitamin A

Another nutrient of particular concern during pregnancy is vitamin A, but expectant women need to be careful about how much of it they consume, because although too little vitamin A can cause developmental problems, too much can also cause birth defects such as facial and heart deformities. Women can thus keep the risk of vitamin A toxicity low by meeting their needs through the consumption of bright orange, deep yellow, and light red vegetables and fruits that are rich in the vitamin A precursor, beta carotene. See Chapter 10 for more information on food sources of vitamin A.

400

The Institute of Medicine recommends that pregnant women between the ages of 19 and 50 years consume 770 micrograms of vitamin A per day, not exceed the Tolerable Upper Intake Level of 3,000 micrograms per day, and stop taking medications that contain vitamin A. The precursor to vitamin A, beta-

Iron

Iron deficiency is the most common deficiency in pregnant women. Iron is used to make hemoglobin, the molecule that transports oxygen through blood, and pregnant women vastly increase their production of hemoglobin to supply oxygen to their fetuses and to help build a fetal blood supply. The daily recommended intake of iron for pregnant women is 27 milligrams per day, compared with only 15 to 18 milligrams for nonpregnant women, yet national surveys have reported that pregnant women generally consume only 15 milligrams per day—

It is difficult for women to meet their increased iron needs from food alone, so supplements of 30 milligrams of iron are typically recommended during the second and third trimesters. Women who don’t take supplements are at an increased risk of suffering from iron-

Other nutrients of importance

Many other nutrients are important for a healthy pregnancy. There’s calcium, which is crucial for the formation of healthy bones, and although absorption is enhanced during pregnancy, the recommendation for pregnant women is still 1,000 milligrams daily. Vitamin D helps to incorporate calcium into bones and also appears to play a role in programming genes in ways that could reduce the risk of chronic diseases; pregnant women should consume 600 IUs (15 micrograms) daily. Iodine is required for normal brain development and growth and recent studies indicate that approximately one-third of pregnant women in the United States are marginally deficient in iodine. The Institute of Medicine recommends 220 micrograms per day for pregnant women.

Omega-3 fatty acids

The omega-