NUTRITIONAL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CHILDREN

Just as adults do, children have specific nutrient requirements set through the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) and Accepted Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDRs), as well as recommendations for food choice through the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans and MyPlate.

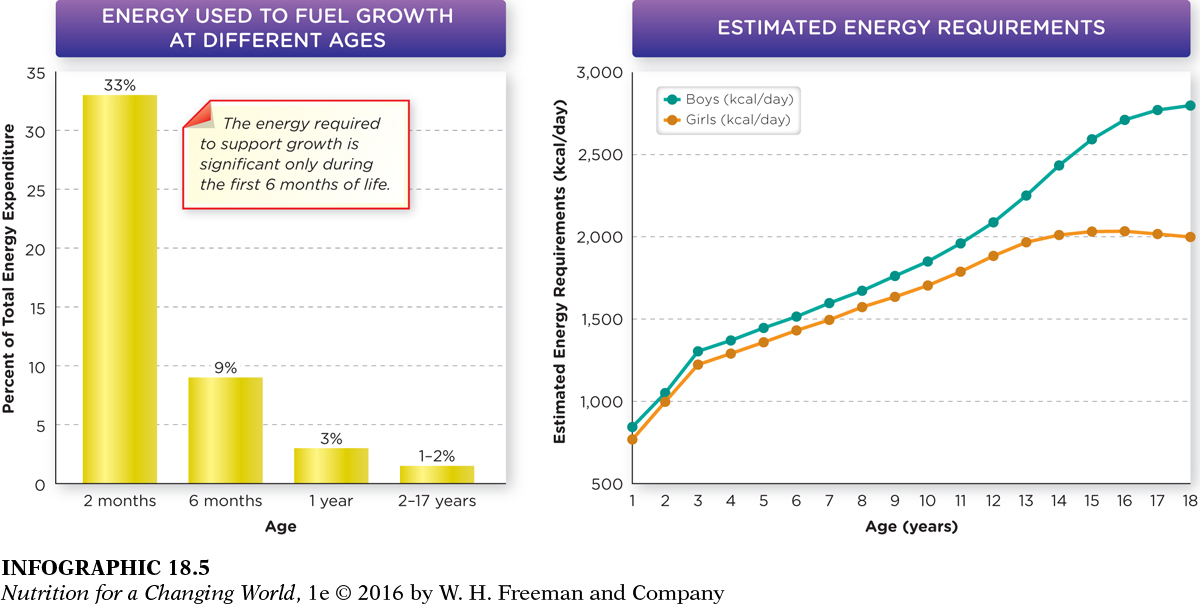

After one year of age, children learn to feed themselves and consume new and different foods. Although their growth is slower than it was during infancy, it continues steadily through the toddler and preschool years and in periodic “spurts” during the elementary school years and early adolescence. Some parents get concerned because their children’s interest in food declines during periods of slower growth, but the trend usually reverses itself during accelerated growth periods. Energy requirements in children, as in adults, are based on age, sex, and activity level. (INFOGRAPHIC 18.5)

Question 18.3

At what ages are the energy requirements for boys and girls very similar? At age 18, how many more kcals do boys require than girls?

At what ages are the energy requirements for boys and girls very similar? At age 18, how many more kcals do boys require than girls?

The energy requirements for boys and girls are similar for ages 1 through 9. They begin to diverge at approximately age 10. Boys require 700 more kcal per day at than girls at age 18.

Children of all ages need adequate amounts of all essential vitamins and minerals, so it’s important that they eat varied and balanced diets that emphasize nutrient-

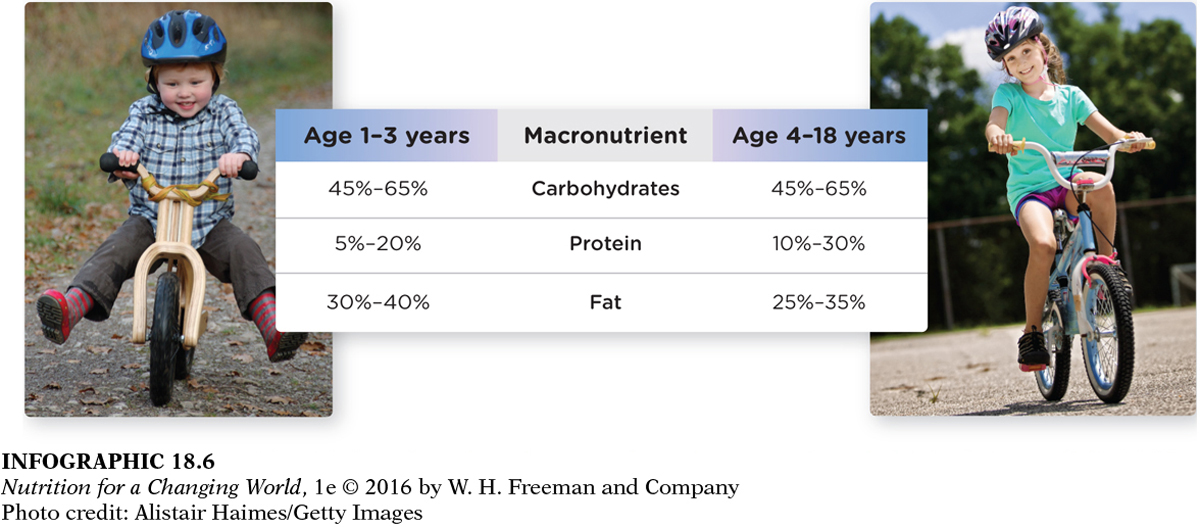

According to the AMDRs set by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), carbohydrates should be children’s primary source of energy, composing 45% to 65% of total calories (the same range recommended for adults). Children need sufficient protein, too—

423

Question 18.4

What AMDRs for children have an upper or lower cut-

What AMDRs for children have an upper or lower cut-

The AMDR for carbohydrates is the same for children and adults: 45%-65%.

The AMDR for protein is lower for children aged 1 to 3 years (5%-20%) and children aged 4 to 18 years (10%-30%) than for adults (10%-35%). The AMDR for fat is higher for children than adults. The AMDR for fat in children aged 1 to 3 years is 30%-40% and for those aged 4 to 18 years is 25%-35%. The AMDR for adults is 20%-35% fat.

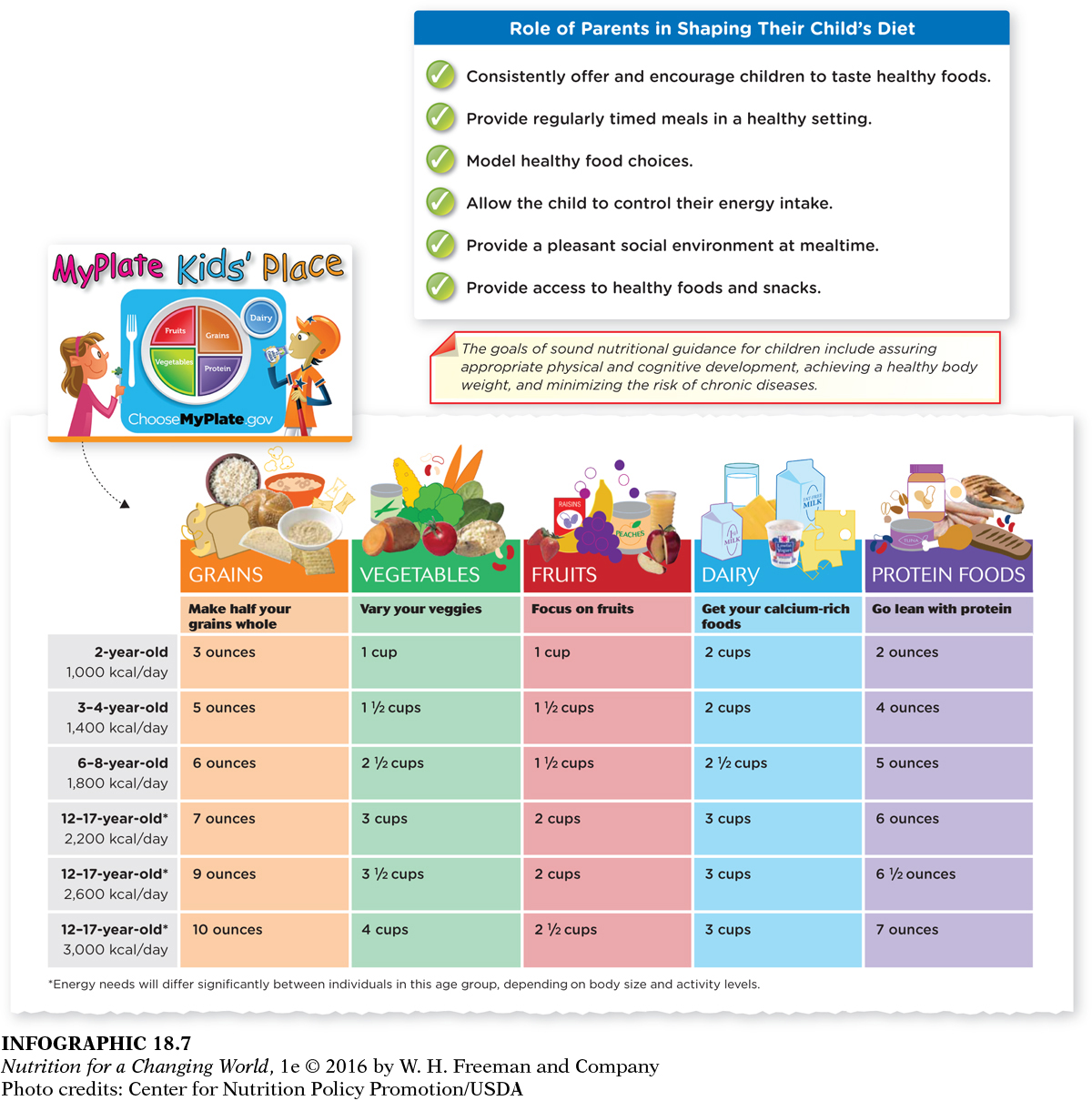

The U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans also provide dietary recommendations for the general public 2 years and older, focusing on three main areas of emphasis. The first is the importance of balancing calories with physical activity to manage weight. The second is that individuals should eat more vegetables, whole grains, fat-

http:/

Question 18.5

What recommendation do you feel children and adolescents typically have the most difficulty achieving?

What recommendation do you feel children and adolescents typically have the most difficulty achieving?

If you look back to Infographic 18.2, you will note that children have particular difficulty meeting recommendations for vegetables and whole grains.

Parents also play an important role in shaping their children’s eating behaviors by establishing the eating environment and modeling food-

424

Young children especially depend on their parents to provide appropriate nourishment, so early parental influences can play an important role in determining a child’s relationship with food later in life. As children grow older, they take more responsibility for feeding themselves and making decisions about food choices, but their tendencies are still strongly shaped by parental influence. For instance, parents can affect children’s dietary practices by determining what foods are offered and when, the timing and location of meals, and the environment in which they are provided. They model food choice and intake and socialization practices surrounding food. Also, how parents interact with their children in relation to eating during mealtimes can influence how children relate to food in general, which can have an impact not only on nutritional choices but also on lifelong food preferences and eating habits. Studies demonstrate that although specific parenting styles are not strongly linked to negative eating behaviors and nutrient-

425

To encourage healthy eating habits, parents should provide their kids with a variety of nutritious foods and encourage—

FOOD JAGS developmentally “normal” habits or rituals formed by children as they strive for more independence and control

Sometimes, children develop particular ways of eating—

426

In addition to a varied and balanced diet, children should also engage in regular physical activity. Yet research suggests that less than half of all U.S. children meet the physical activity guidelines set by the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. These recommend that children and adolescents older than six years participate in 60 minutes or more of developmentally appropriate and enjoyable physical activity per day. Younger children should play actively several times a day. It’s fine for kids to be active for short bursts of time rather than sustained periods, as long as these bursts add up to meet recommendations.

Unfortunately, children who don’t meet the guidelines also tend to have lower diet quality—