ENERGY RECOMMENDATIONS

Two recommendations about energy intake are also included in the DRI. The first is the Estimated Energy Requirement (EER), which is similar to the EAR in that it represents the average amount of calories a healthy person of a particular age, sex, weight, height, and level of physical activity needs in order to maintain his or her weight. This value meets the energy requirements of 50% of the population, and actually exceeds the needs of nearly 50% of individuals.

ESTIMATED ENERGY REQUIREMENT (EER)

estimated number of calories per day required to maintain energy equilibrium in a healthy adult; this value is dependent on age, sex, height, weight, and level of physical activity

11

An imbalance in macronutrient intake (particularly of fat and carbohydrates) can increase the risk of several chronic diseases. For this reason the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDRs), have been established to provide a healthy range of intakes for carbohydrates, protein, and total fat (also some specific types of fat) expressed as a percentage of total calories. Adults can obtain adequate amounts of macronutrients when their carbohydrate intake falls between 45% and 65% of total calories, their protein intake falls between 10% and 35% of total calories, and their fat intake is within 20% and 35% of total calories. Individuals who regularly eat below or above these ranges, put themselves at risk of getting too few essential nutrients or of developing chronic diseases.

ACCEPTABLE MACRONUTRIENT DISTRIBUTION RANGE (AMDR)

the range of energy intakes that should come from each macronutrient to provide a balanced diet

But who knows how to use the DRIs to determine what they should eat day to day? Given how difficult it can be to analyze individual diets, most people who use DRIs as a nutritional tool are researchers and registered dietitians. However, some publicly available computer programs and software applications can track meals and provide dietary information, making DRIs a tool that nonexperts can use, too. We will explore some other useful tools in Chapter 2.

■ ■ ■

The DRIs vary depending on the specific nutritional needs of different groups of people—

This is something Robert Waterland experienced first-

During his time in Stunkard’s lab, Waterland helped set up a research study of infants born to mothers who were either of healthy weight or obese. The moms brought their babies into the laboratory, where Waterland and his team spent the day measuring how much food the babies consumed, checking their body composition, and even observing how they ate—

Since the moms had to spend all day in the lab, including even the babies’ naptimes, they would sometimes sit down with Waterland to chat. Over time, a few of the obese moms asked him if there was anything they could do now, when their babies were very little, to prevent them from becoming obese later in life. “The first time someone asked me, I didn’t think much of it,” recalls Waterland. “But the second time, I got intrigued.”

He went to the library, scanned the scientific literature, and discovered the Dutch famine study. From then on, he was hooked on how early nutrition—

12

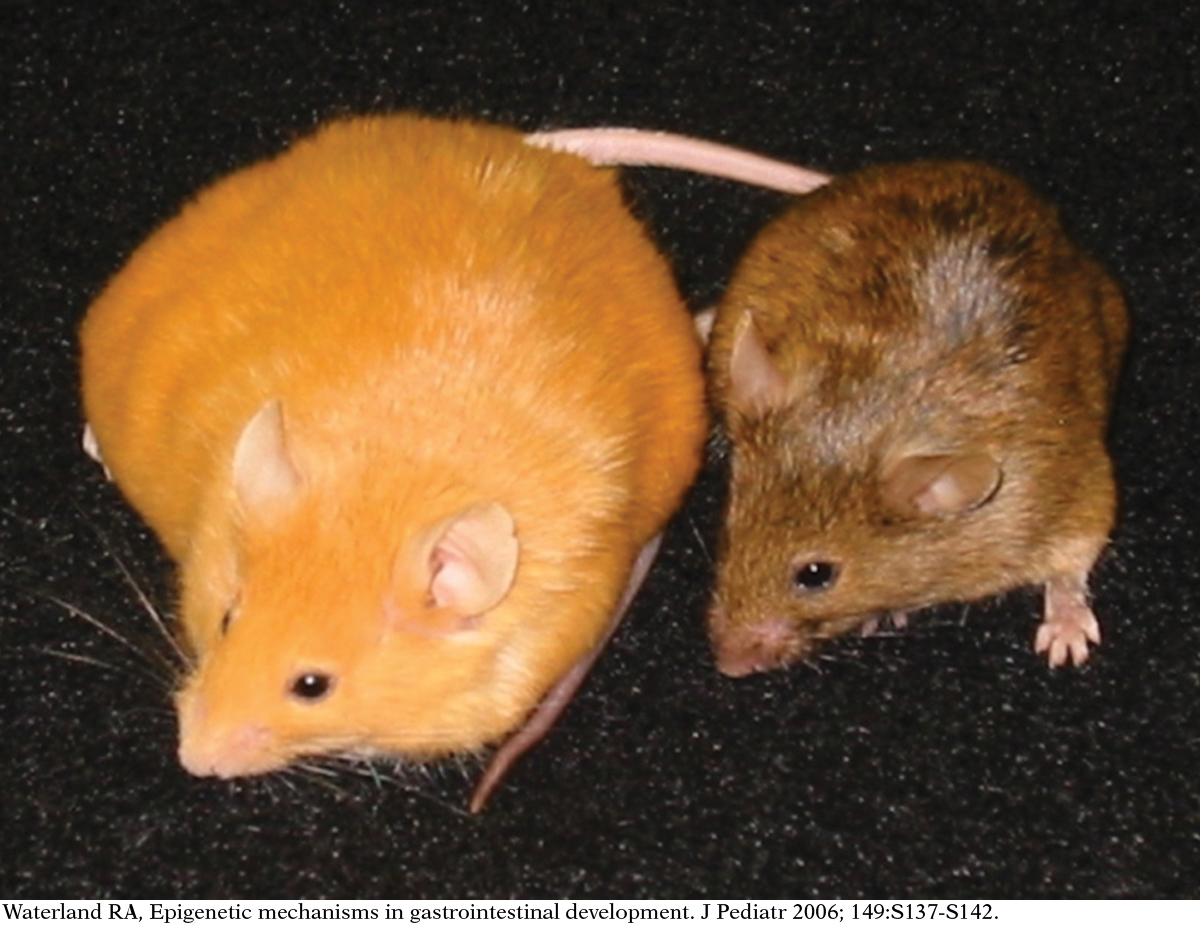

After working in Stunkard’s lab, Waterland entered graduate school to continue studying the multigenerational effects of nutrition. During that time, another study was published that deepened his interest even further. This study showed that the diet of pregnant mice appeared to affect the coat colors of their young. Normally, when this strain of mice gives birth, the litter contains babies with coats in a range of colors—

The field of genetics describes how genes encoded in DNA are passed on between generations (from parents to child), but sometimes the DNA in our genes can become modified after it’s inherited, which can change traits in the current generation (as well as in subsequent ones). This explains why identical twins—

Waterland was interested in epigenetics; he simply had to understand more about why a mother’s diet during pregnancy could affect the future health of her children.