UNDERSTANDING THE NUTRIENT DENSITY AND ENERGY DENSITY OF FOODS

NUTRIENT DENSITY the amount of nutrients supplied by a food in relation to the number of calories in that food; black beans, for example, provide much protein, fiber, vitamins and minerals relative to their calories

ENERGY DENSITY the amount of energy or calories in a given weight of food; generally presented as the number of calories in a gram (kcal/g)

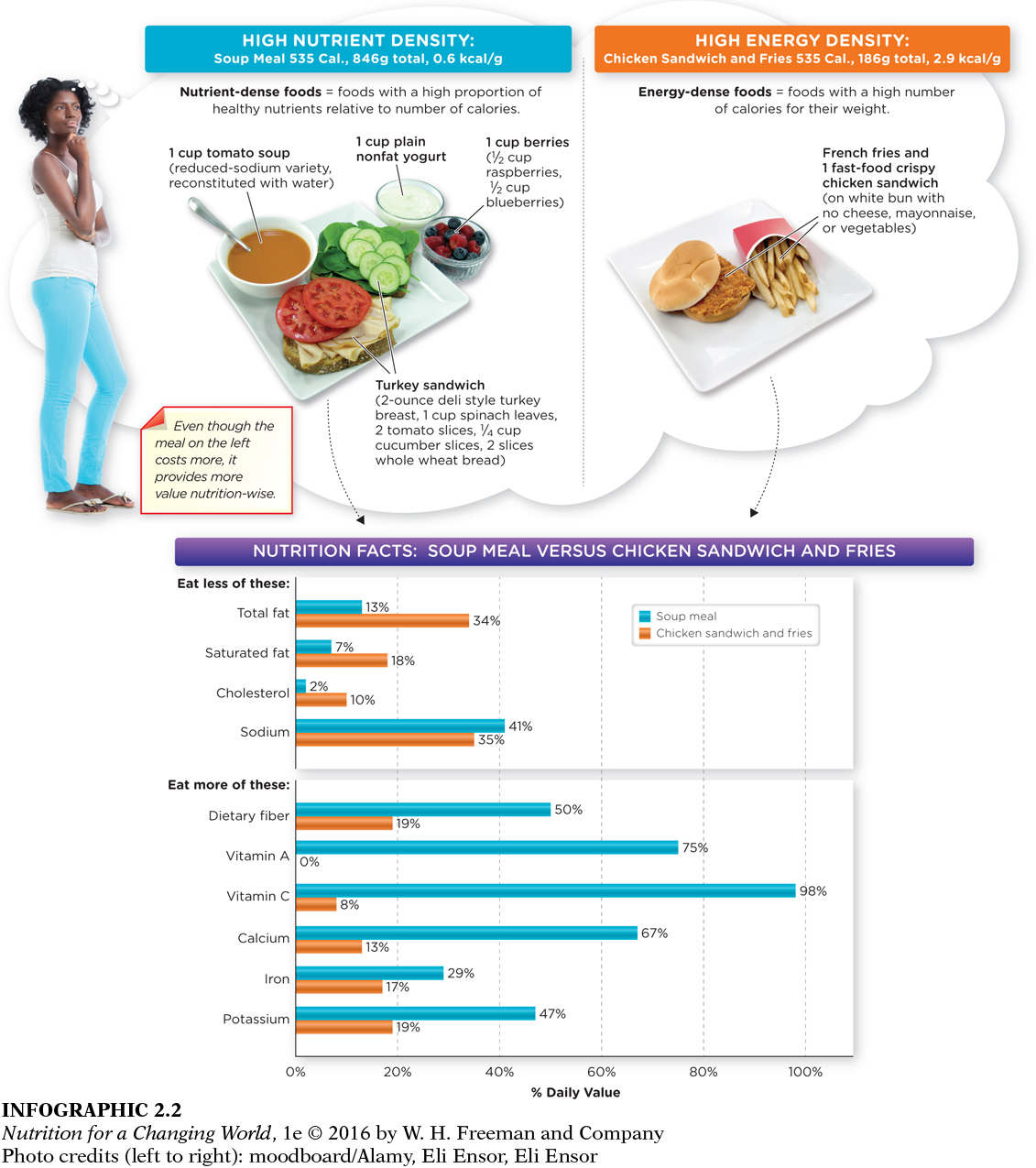

Healthy diets are full of foods with high nutrient density; these foods contain many beneficial nutrients relative to calorie content. Nutrient-dense foods are a “good deal” nutritionally in that they provide many nutrients at a low calorie “cost.” Healthy diets also take into consideration the energy density of foods. (INFOGRAPHIC 2.2) Foods that are rich in calories relative to weight are considered energy dense. Nutrient-rich nuts fit this bill, but many foods are dense in calories and low in nutrients, such as cookies and chips. Unfortunately, food deserts are generally well-supplied with energy-dense, convenience-store foods, whereas nutrient-dense fruits and vegetables are harder to find.

26

Question 2.2

Which meal will delay the return of hunger the longest? Why?

Which meal will delay the return of hunger the longest? Why?

The soup meal will delay the return of hunger the longest because it has more volume (846 grams compared with 186 grams in the chicken meal) and also contains more dietary fiber (50% DV compared with 19% DV in the chicken meal).

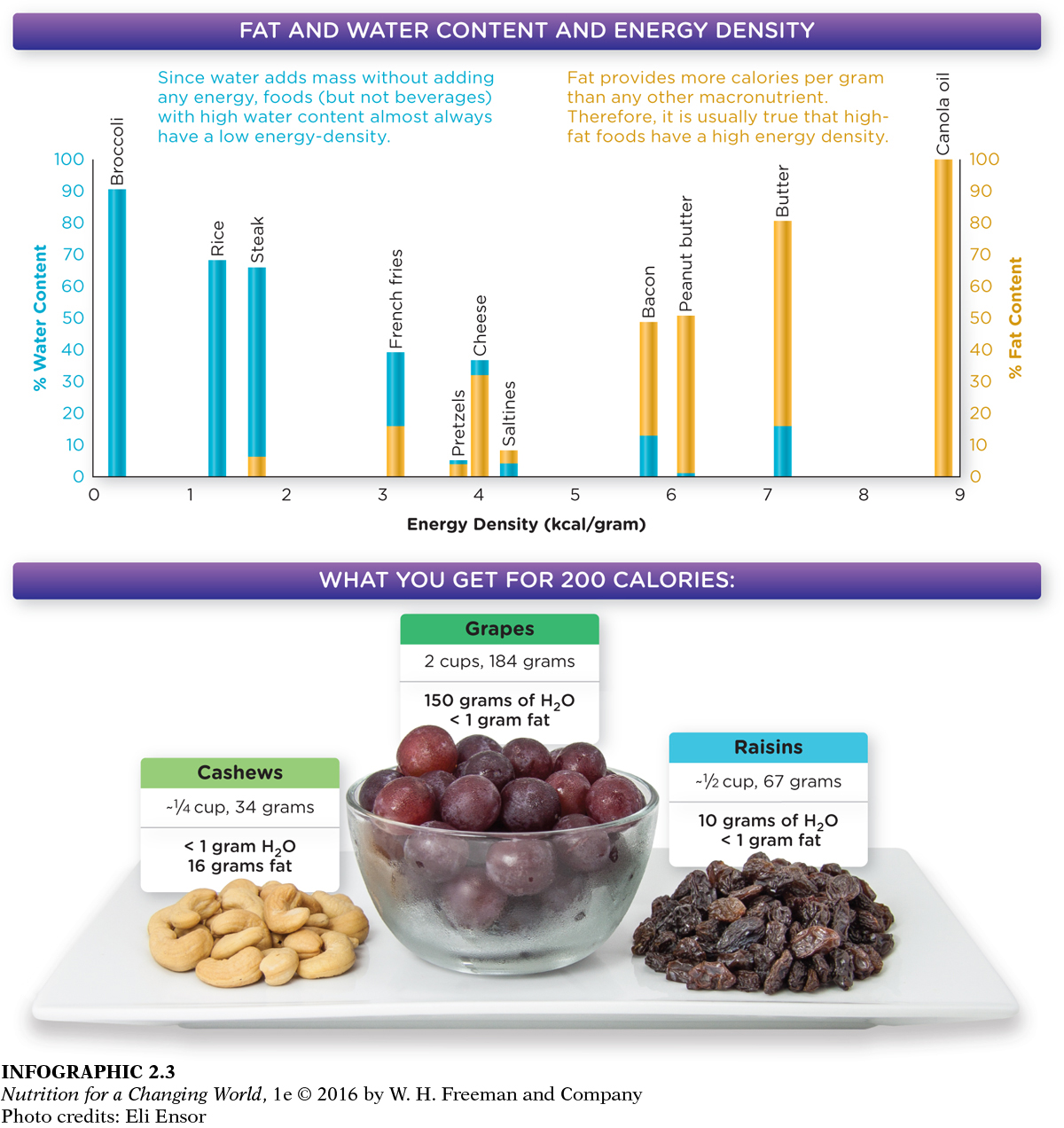

The water, fiber, and fat content of foods is the primary factor that determines energy density. As the water and fiber content of food increases, they generally decrease the energy density of food by adding weight and volume but no (or very few) calories. Fat content has the opposite effect—the more fat is added to food, the more energy dense it becomes, since fat has more than twice as many calories per gram as either protein or carbohydrates. In general, as the energy density of foods increases, the nutrient density decreases. Most vegetables are nutrient dense as they provide lots of essential nutrients relative to their calorie content. (INFOGRAPHIC 2.3)

27

Question 2.3

Why does butter have slightly fewer calories per gram than canola oil?

Why does butter have slightly fewer calories per gram than canola oil?

Butter has slightly fewer calories per gram than canola oil because there is some water in butter that reduces its energy density.

¦ ¦ ¦

Although historically there have always been people with little access to a variety of nutrient-dense foods, the problem of food deserts in many cities started in the 1950s, says Gallagher, when wealthy residents moved away and grocery stores often went with them. Even some rural areas have become at risk of becoming food deserts, since local farms that used to provide a variety of produce have since been consolidated and converted into farms that grow mostly corn or soybeans.

28

One city that Gallagher studied is Chicago, Illinois. Chicago in the 1990s could be a desolate place. Beautiful historic buildings had become decrepit gathering places for drinking and street fights. Gallagher—who has a Master’s degree in urban planning and community development—would pass block after block with no major grocery store. It’s not prejudice that causes grocery stores to shy away from poor communities, she says, it’s likely just a business decision. “If a developer goes around and sees there are no grocery stores, they assume people don’t want or need one; that there is no market for grocery stores.”

But over time, Gallagher participated in projects such as a successful urban community garden, which suggested that people living in neglected areas would eat healthy foods if they became available. She began analyzing block-by-block data on the location of grocery stores in Chicago, trying to identify patterns.

In 2006, over lunch with a representative of a bank headquartered in Chicago, she casually mentioned the project she was working on. Perhaps she could analyze data to determine whether their risk of dying of various diseases is at all related to the types of nearby stores. Intrigued, “he funded it right away,” recalls Gallagher.

Little did either of them know what she would find—and the firestorm it would spark.

¦ ¦ ¦