OVERVIEW OF MECHANICAL AND CHEMICAL DIGESTION

MECHANICAL DIGESTION physical breakdown of food by mastication (chewing) and mixing with digestive fluids

CHEMICAL DIGESTION digestion that involves enzymes and other chemical substances released from salivary glands, stomach, pancreas, and gallbladder

Digestion is comprised of two processes: mechanical and chemical digestion. Working together, these two processes break down the nutrients in food into manageable pieces so that they can be processed by our bodies, but each has its own unique spin on the process. Mechanical digestion is the physical fragmentation of foods into small particles, while chemical digestion breaks chemical bonds to cleave large molecules into smaller ones.

Mechanical digestion begins in the mouth, where teeth crush and tear food into small bits. It continues in the stomach, as forceful contractions vigorously churn food. This churning action disperses the small food fragments and exposes large molecules to the digestive fluids that will dismantle them. In many cases, mechanical digestion is all that is required to release many vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals from foods that are then taken up by mucosal cells lining the small intestine.

Gastrointestinal Motility

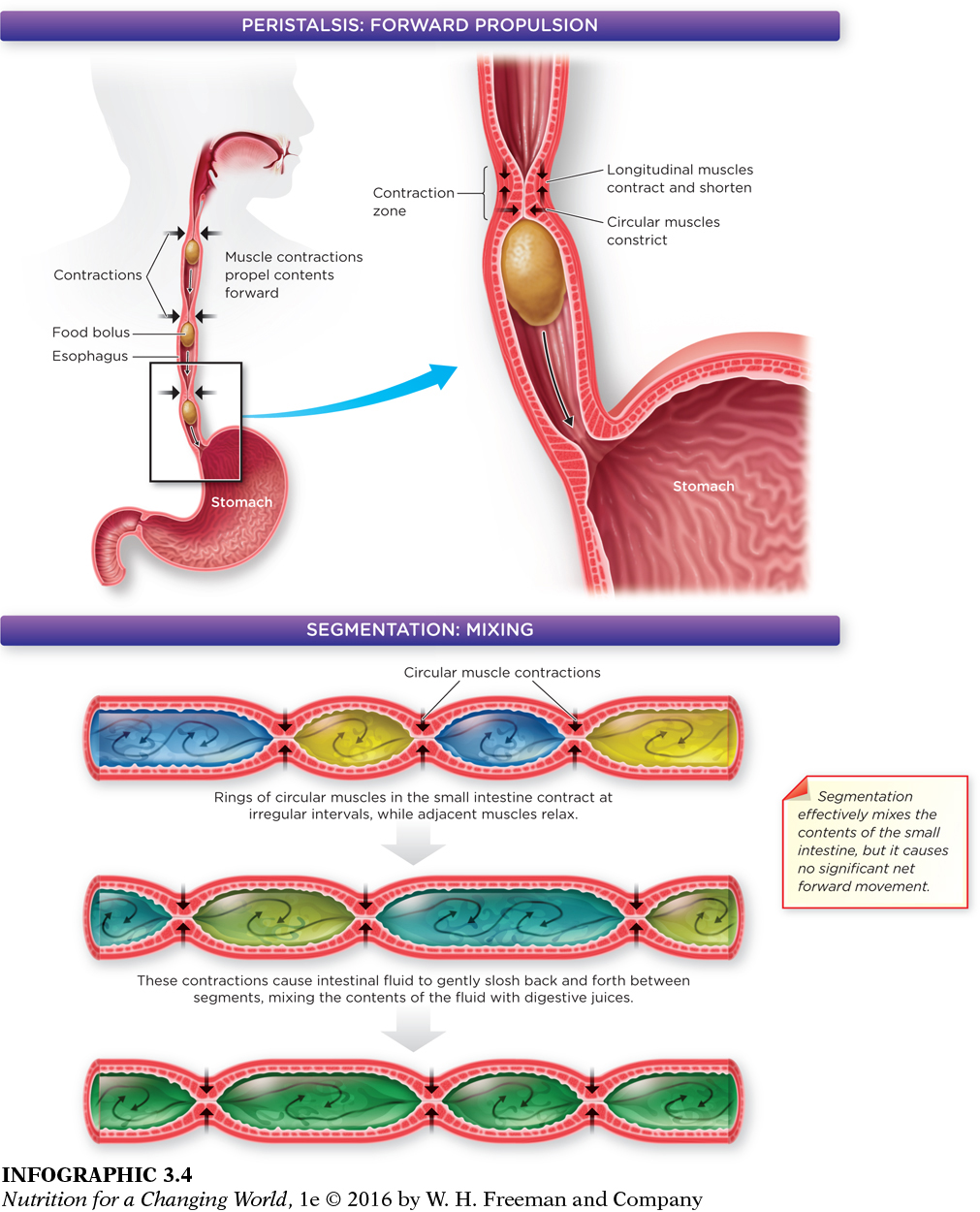

PERISTALSIS rhythmic, wavelike contractions of the smooth muscle of the GI tract

SEGMENTATION circular muscles in the small intestine contract to mix intestinal contents with digestive fluids and bring nutrients in the intestinal fluid in contact with the intestine’s absorptive surface

Motility is a term used to describe the contractions of the GI tract’s smooth muscles that mix food with digestive fluids and propel food along the length of the tract. There are two fundamental patterns of these muscle contractions: peristalsis and segmentation. Peristalsis creates propulsive muscle contractions to move food forward through the complete length of the GI tract, from the esophagus to the anus. Segmentation, in contrast, occurs when circular muscles in the small intestine contract in an uncoordinated fashion so that fluid contents gently slosh back and forth between the segments. These contractions serve to mix intestinal contents with digestive fluids and bring nutrients in the intestinal fluid in contact with the intestine’s absorptive surface. Similar segmentation contractions also occur in the colon. (INFOGRAPHIC 3.4)

54

55

Question 3.4

Identify which type of contraction (segmentation or peristalsis) is responsible for the elimination of feces.

Identify which type of contraction (segmentation or peristalsis) is responsible for the elimination of feces.

The elimination of feces is accomplished through peristalsis, which pushes material forward through the digestive track. Segmentation mixes the material without pushing it forward.

Enzymes and Hormones in Digestion

Chemical digestion is the form of digestion that involves enzymes and other substances released from salivary glands, as well as from the stomach, pancreas, and gallbladder. It takes place in the mouth, small intestine, and stomach.

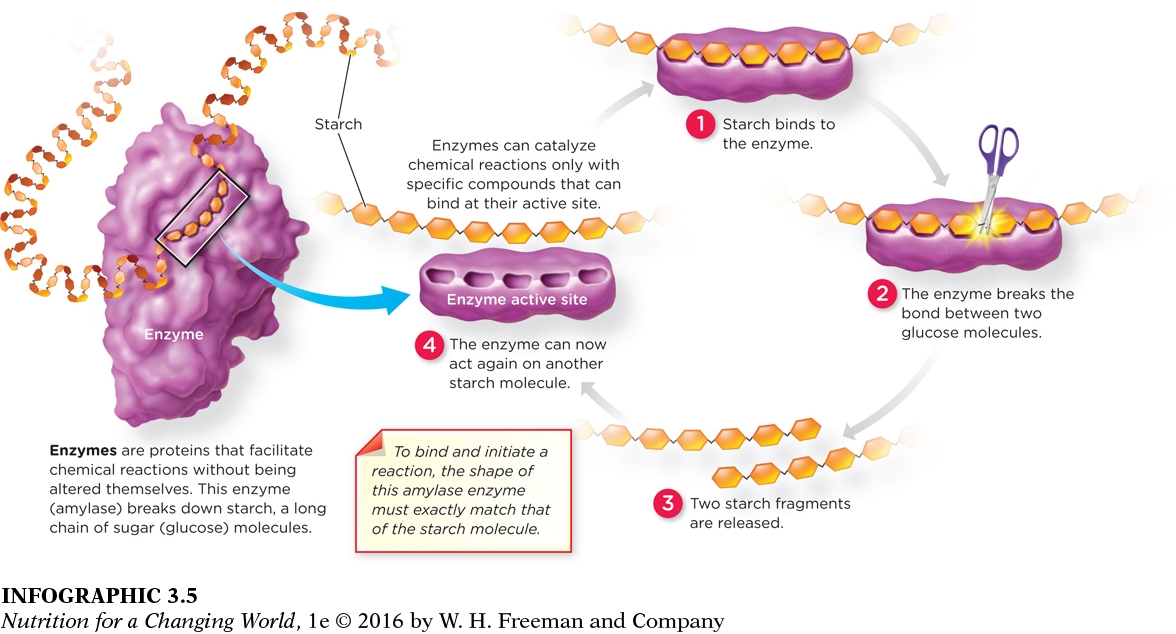

ENZYMES protein molecules that catalyze, or speed up, the rate at which a chemical reaction produces new compounds with altered chemical structures; enzyme names end in the suffix “-ase”

Without the work of enzymes, digestion (and many other body processes) could not occur. An enzyme is a protein molecule that functions to catalyze, or speed up, the rate at which a chemical reaction produces new compounds with altered chemical structures. These reactions may subtly alter the chemical structure, or they may produce dramatically larger or dramatically smaller molecules. Enzymes have a specific shape that will fit only molecules that have a coordinating shape, like matching pieces of a puzzle. As facilitators, the enzymes bind to their coordinating molecule, initiate a chemical reaction, and move on. Thus enzymes can participate in these chemical reactions many times without being altered themselves. The salivary glands, stomach, pancreas, and the small intestine produce enzymes to break down the chemical compounds in food into units that are small enough to be absorbed. You can recognize enzymes by their names: They end in the suffix “-ase,” with the first portion of the enzyme’s name identifying the type of molecule they digest. For example, the enzyme “protease” digests protein. (INFOGRAPHIC 3.5)

Question 3.5

Why won’t this enzyme break down lipids or proteins?

Why won’t this enzyme break down lipids or proteins?

The starch molecule in the illustration can bind to the amylase enzyme because the shape of the enzyme perfectly matches the shape of the starch molecule. Because lipids and proteins have different structures, it is impossible for a lipid or a protein to bind with an amylase enzyme.

HORMONES chemical substances that serve as messengers in the control and regulation of body processes

In addition to enzymes, other chemicals, such as hormones, are produced by the various organs of the digestive system. Hormones are your body’s chemical messengers. Together with the nervous system, these hormones regulate motility, appetite, and the release of secretions into the GI tract.