Human Patterns over Time

VIGNETTE

“With courage, you can travel anywhere in the world and never be lost. Because I have faith in the words of my ancestors, I’m a navigator.”

MAU PIAILUG

In 1976, Mau Piailug made history by sailing a traditional Pacific island voyaging canoe across the 2400 miles (3860 kilometers) of deep ocean between Hawaii and Tahiti. He did so without a compass, charts, or other modern instruments, using only methods passed down through his family. To find his way, he relied mainly on observations of the stars, the sun, and the moon. When clouds covered the sky, he used the patterns of ocean waves and swells, as well as the presence of seabirds, to tell him of distant islands over the horizon.

Piailug reached Tahiti 33 days after leaving Hawaii and made the return trip in 22 days. His voyage resolved a major scholarly debate over how people settled the many remote islands of the Pacific without navigational instruments, thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. Some thought that navigation without instruments was impossible and argued that would-be settlers simply drifted about on their canoes at the mercy of the winds, most of them starving to death on the seas, with a few happening upon new islands by chance. It was hard to refute this argument because local navigational methods had died out almost everywhere. However, in isolated Micronesia, where Piailug lives, indigenous navigational traditions survive.

After the successful 1976 voyage, Piailug trained several students in traditional navigational techniques. His efforts have become a symbol of cultural rebirth and a source of pride throughout the Pacific. In 2007, the protégés of Mau Piailug sailed from Hawaii through the Marshall Islands to Yokohama, Japan, to celebrate peace and the human need to stay connected with nature. [Source: Facts on File, 2007. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

603

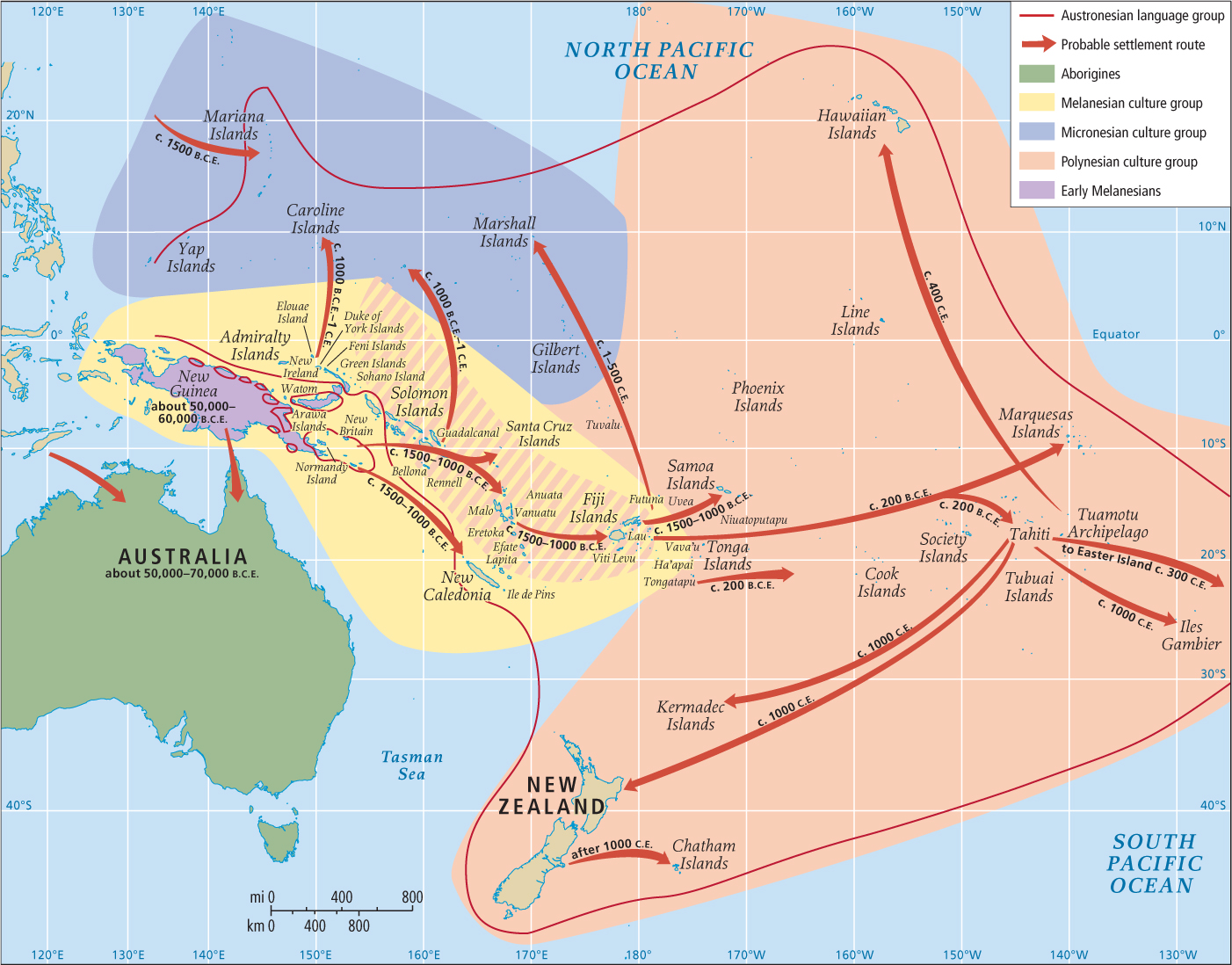

The Peopling of Oceania

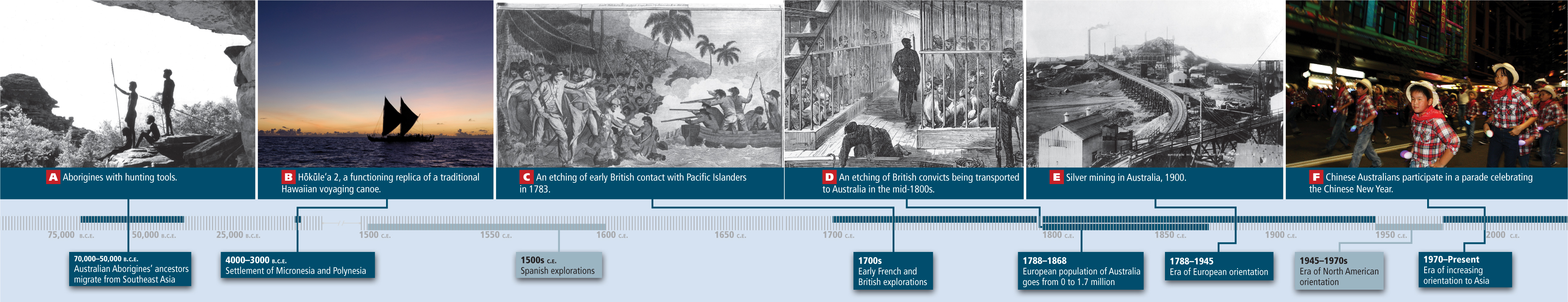

The longest-surviving inhabitants of Oceania are Australia’s Aborigines, whose ancestors (the Australoids) migrated from Southeast Asia 50,000 to 70,000 years ago (Figure 11.13; see also Figure 11.14A), at a time when sea level was somewhat lower. Amazingly, some memory of this ancient journey may be preserved in Aboriginal oral traditions, which recall mountains and other geographic features that are now submerged under water. At about the same time that the Aborigines were settling Australia and Tasmania, related groups were settling nearby areas.

Aborigines the longest-surviving inhabitants of Oceania, whose ancestors, the Australoids, migrated from Southeast Asia 50,000 to 70,000 years ago over the Sundaland landmass that was exposed during the ice ages

Melanesians, so named for their relatively dark skin tones, a result of high levels of the protective pigment melanin, migrated throughout New Guinea and other nearby islands, giving this area its name, Melanesia. Archaeological evidence indicates that they first arrived more than 50,000 to 60,000 years ago from Sundaland (see Figure 10.5), a now-submerged shelf exposed during the Pleistocene epoch. They lived in isolated pockets, which resulted in the evolution of hundreds of distinct yet related languages. Like the Aborigines, the early Melanesians survived mostly by hunting, gathering, and fishing, although some groups—especially those inhabiting the New Guinea highlands—eventually practiced agriculture.

Melanesians a group of Australoids named for their relatively dark skin tones, a result of high levels of the protective pigment melanin; they settled throughout New Guinea and other nearby islands

Melanesia New Guinea and the islands south of the equator and west of Tonga (the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Fiji, and Vanuatu)

Much later, between 5000 to 6000 years ago and as recently as 1000 years ago, linguistically related Austronesians (a group of skilled farmers and seafarers from southern China who migrated to Southeast Asia; see Chapter 10) settled Micronesia and Polynesia, sometimes mixing with the Melanesian peoples they encountered. Micronesia consists of the small islands that lie east of the Philippines and north of the equator (see the Figure 11.1 map). Polynesia is made up of numerous islands situated inside a large irregular triangle formed by New Zealand, Hawaii, and Easter Island. (Easter Island, also called Rapa Nui, is a tiny speck of land in the far eastern Pacific, at 109° W 27° S, not shown in the figures in this chapter.) Recent experiments run by Polynesians (see the voyaging vignette) have provided evidence that ancient sailors could navigate over vast distances, using seasonal winds, astronomic calculations, bird and aquatic life, and wave patterns to reach the most far-flung islands of the Pacific. The Polynesians were fishers, hunter-gatherers, and cultivators who developed complex cultures and maintained trading relationships among their widely spaced islands.

Micronesia the small islands that lie east of the Philippines and north of the equator

Polynesia the numerous islands situated inside an irregular triangle formed by New Zealand, Hawaii, and Easter Island

604

In the millennia that have passed since first settlement, humans have continued to circulate throughout Oceania. Some apparently set out because their own space was crowded and full of conflict, or food reserves were declining. It is also likely that Pacific peoples were enticed to new locales by the same lures that later attracted some of the more romantic explorers from Europe and elsewhere: sparkling beaches, magnificent blue skies, scented breezes, and captivating landscapes.

Arrival of the Europeans

The earliest recorded contact between Pacific peoples and Europeans took place in 1521, when the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan (exploring for Spain) landed on the island of Guam in Micronesia. The encounter ended badly. The islanders, intrigued by European vessels, tried to take a small skiff. For this crime, Magellan had his men kill the offenders and burn their village to the ground. A few months later, Magellan was himself killed by islanders in what became the Philippines, which he had claimed for Spain. Nevertheless, by the 1560s, the Spanish had set up a lucrative Pacific trade route between Manila in the Philippines and Acapulco on the west coast of Mexico. Explorers from other European states followed, first taking an interest mainly in the region’s valuable spices. The British and French explored Oceania extensively in the eighteenth century (Figure 11.14C).

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about the human history of Oceania, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

k5EVg++n95mx9fZHbpfpBwO9d3fB5/BDLxvzDuEekTpgcUHK7NdOzZZI71M6mYDYrJ4RtXLR2PUrR8lcmEyvP5DzcsxuxgDoZRyO1XxT1Ex96X/1m2zYfqcjRe4nPkPqqVfStIVz4SaG44SISYo/I+sEjm01gMNgfqCt2hq46HYSZE8unEPRBGwnfG9eeyQvvPLanw4oiM+EYq/hrPrWNjcd7l0w5HIy7fhyXwj3iihZx09R6V8sDZwkix/xiDsdPr4zHHqRH5FGrm6RMj9hOU7UXViu2VJAQuRyn4assrc6PkLmO/7TTWogjdEOQq1qbv2uCidFTZHzRSznUJnscky6yOo2xWB8FYJCdNOHeGVN4Cp2dcuTSQ==Question

UpvasBs9Be2yoWHC1O1q4VDuYSnKkIn1QJvuI5YD3BLktAhPJl+gwCQN49eO/CxJO4jwUysUGVwQEwOs0I7tAK3ivxWDvwW7D5wE5c+SmiaKHf0yi0/1itKXpx6orGhKaY8TQlvjOQtaFgF1IlJBNwQ5tecKJB9CmQrx254wYCJW/q2xmXZxOFGyDPGv6tyQnfpSGJ9X+UigkvGzDkyfy1Ypqf1Ed/bJsXzkwnr0Tp20UCC0dVY3KTxun5FMn3/p16DrHd6Ct7IwpkQ2F/PWTG/FhXFGtChre7FyxHcPST4bSuDNb8OK1bkFdHEEjDUqBjAiBK2CncJRgP83Y8tERhEZZ9GxfjMkk5BDVuczqi7sOho57iOUN9tnTeBeNCWiSsCTBVHen44UZKgje/wBdnyU5mw/JiZODal2YqlxbfwhcqJ9RevhUM8/uIaUWOe9woe+qpqnsreV4u+J2Jxwukh8peZuZtp/P3uhMKXkgpKP64nEEcdTe4518HKe5Fi4f+fWLCaXuqTpPwMOwGzpW3UeQL4=Question

QR99n6UlAe9Hgj/GgF1dcohiJxb0CFoX77ExzbvkMuBKqq/FR0ficU/bF815u8wl5m4uTVxikYpwTgNV8Z2GGagFiv1LChACpVFZjK5SPhf/YcAq9RC8uvGjvnoiGWpOf13yMUfnKd3ANcYjZbuF9FIrFN/nxw45H2BEZoxhsGYQ9G1d42RaMA+N8a5TUhrF9W2Baz/UM+2y4V4h5bArADp2D2zzTVCR1YvA14ij5c24ewgrWzXELCCpRqwHCYrkc4soRxA0j1aEK7xLKnbRmKsd88xS6naG+6nHjbHKOmhWuDqnaF5nQ1wmjgL/nkmp/HvUb8D/1qgLFRh2Ex7tp8eYoB2xVjMo0ta4Pb4QkX7O6lUoKilyiUQUE+tDByK7tasVbbQTTajehakKKf702zqyvcue+VC5T47IdBrlSe4ffXcjaJLbvTPFpImlZx2O+YDvqVg85nwa2SvJQuestion

OyJZLQw30dl54Jx4k2xplH8ZYL1p92A7ZCmtIS9P5zbDsJmJnZqcoCD0Q/tUtiCxSYncbcxFKO3h79XVIfxEYeeTj376MIhLCwTnCq8+oqfDiOHZ2pFPzcq2FX5ZF0T+LiiNmXuXVvgI8ehr7vvRV5OTiqfxSnCdujBPb6ACBbx8A5JfJ4ehO2E83v1xiGj7I9cqBT/xDIyPaG8UfiZlErcgYiliezAy4D3XMCsrlY7ANPyJKjPuTid8VjXPoLWt3Gbo4nEw21+Aju3ghNaPLq7dyN9ZYGDEStBI3PLAEr2Y2+MQY+je6pwxx/XxVDC5ii/fRIRj6fQVXhiR6Ivs3xj2XmYhLIdFLT4wm2iONvPtIrvz64FaGkXI1wLiXVEAo9r9bQviF1QGGYYhyTiE7Ds4Ht0xNDqLulUmAkI8r4f+uV6++4WtIZzjSHq63G/WXTpCFB4fDOiAdIPty6ko+y0DDW/RmLGvK56lLLRmunAZ4xYEdKXA9LPZ5sLQPvK5tM7VAgBTzbarvyURdw5SWN6lP201Ca7aoe/V6oc//18jVDN7BG4X4kQJKMfIvFxEA7BscL/CmE0E533vU2OIbJllzpOI4XZzXiKLL9xHhYJhmYfeAsKOGTmg7qQT+6LlFiz6dajvsynszr9f1GlXLigTlzvf/phVrsgCnrLZozKsWhE4JYmoGWsxUPv6y19TF3IX7Ro5MW2VBjZyEJKXNGY16tANJuJEtxkBADpQqMdReFn9E+KUPO7xiEd/ibNVsWmSVe2HnCxwbrrv3jjvu3SRz+yjFLuzWbA9h67FtzyFj2nvhONsj2JUkiaMRO4UBvy5nFJE37+aRm8GUYY2gYQU+pIuBUM9Nzn7sSWPrZ3jV4c4MjLaw+Z3GYvi7GuwgjBjiuW3s0iXEYs8sB67vjDJNMmFoXTCGvGNrWtCtnRyuXefQuestion

TSvV2fVbuOCUUkwY7fGjDUHCUxHSq3kOyVQEUXfH7LpE3miRm50sG78VFtz5eR6XOyPEUcr/ywEY+7D+0yx8ojHxdL33SmrkH7lJXLHowWapeVzJkHaqfkTfWJU0W1IyDDpbAumQ/8gHf5a3kywIT+TUtjyMFceQJVp5xfc5fRtKR2pZVsjrjAQ7PW6ylJMR0GsUepBUcqoSIQmKPhAg8s3+oFY9WVNR26Z8C1ErVyNoEbMN6mYb45C6JK962mm+Urix+z6mlNKoWrbPt70cPAkcemJsxI0d0b7bmWQrTwEa8zQYHds48yk+lIzfji94ciEoebs68iovLaQ2VFhqRAN5HZYHLlpkRQuwZN6pVQkz67rvCzkF41JNWM79YqSKrMLAIhwngxGAT0yE0XGQ4m/mR7KLaKLs/sjLw2bhQiK+rCNH6WSGHQ==Question

plwxyRRwecpsxq4UZzrlC0kAe2yIwbz/mE7kHYYfQZZ8fUiojwO1g9Bkhcj7sKzVwqQ07DnrgTOoqXKhZuqA0VBRJ2OrC/1nvqRkqT67l52nM08nrD9WfhbFCarc2y/N5a6AP2lNHQucZe7s7vjB7R/ynk0uvOi5iIxYluSWXk31qpcEWBZVzIaeKUWW0VPHIBEZtXgt59kGSCPJ+r5FaQThQD7BI1bCZJ6eoWtqrIj+cJssrFLKIKjv/1wtIQVMcxtC7puQxgtTEX9UnvQst/3lYeSc4JOCptBLg6SogxkSlZR/8uYutwopn1qqH2HRTHJX0sBx8q3vqzk2BOSg1MtCRnYq3E9PBD6djP/b0UQSJabhvhCcRLZjQp99V2RssvcIUOl17QJY7TqT41am/n3feUU=605

The Pacific was not formally divided among the colonial powers until the nineteenth century. By that time, the United States, Germany, and Japan had joined France and Britain in taking control of various island groups. As in other regions, European colonization of Oceania emphasized extractive agriculture and mining. Because native people were often displaced from their lands or exposed to exotic diseases to which they had no immunity, their populations declined sharply.

The Colonization of Australia and New Zealand

Although all of Oceania has been under European or U.S. rule at some point, the most Westernized parts of the region are Australia and New Zealand. The colonization of these two countries by the British has resulted in many parallels with North America. In fact, the American Revolution was a major impetus for “settling” Australia because, once the North American colonies were independent, the British needed somewhere else to send their convicts. In early nineteenth-century Britain, a relatively minor theft—for example, of a piglet—might be punished with 7 years of hard labor in Australia (see Figure 11.14D).

A steady flow of English and Irish convicts arrived in Australia until 1868. Most of the convicts chose to stay in the colony after their sentences were served. They are given credit for Australia’s rustic self-image and egalitarian spirit. They were joined by a much larger group of voluntary immigrants from the British Isles who were attracted by the availability of inexpensive farmland. Waves of these immigrants arrived until World War II. New Zealand was settled somewhat later than Australia, in the mid-1800s. Although its population also derives primarily from British immigrants, New Zealand was never a penal colony.

Another similarity among Australia, New Zealand, and North America was the treatment of indigenous peoples by European settlers. In both Australia and New Zealand, native peoples were killed outright, annihilated by infectious diseases, or shifted to the margins of society. The few who lived on territory the Europeans thought undesirable were able to maintain their traditional ways of life. However, the vast majority of the survivors lived and worked in grinding poverty, either in urban slums or on harsh cattle and sheep ranches. Today, native peoples still suffer from discrimination and maladies such as alcoholism and malnutrition. Even so, some progress is being made toward improving their lives. In 2008, the newly elected prime minister of Australia, Kevin Rudd, officially apologized to Aboriginal people for the treatment they have received since the land was first colonized.

Closely related to attitudes toward indigenous people were attitudes toward immigrants of any color other than white. By 1901, a whites-only policy governed Australian immigration, with favored migrants coming from the British Isles and (after World War II) southern Europe. This discrimination persisted until the mid-1970s, when the White Australia policy on immigration was ended. In New Zealand, where similar racist attitudes prevailed, there was never an official whites-only policy, and by the 1970s, students and immigrants were arriving from Asia and the Pacific islands. Controversy over immigration in Australia and New Zealand has recently centered on the arrival of refugees by boat from various parts of Asia (see Figure 11.23D).

Oceania’s Shifting Global Relationships

During the twentieth century, Oceania’s relationship with the rest of the world went through three phases: from a predominantly European focus to identification with the United States and Canada to the currently emerging linkage with Asia.

Until roughly World War II, the colonial system gave the region a European orientation. In most places, the economy depended largely on the export of raw materials to Europe (see Figure 11.14E). Thus, even when a colony gained independence from Britain, as Australia did in 1901 and New Zealand in 1907, people remained strongly tied to their mother countries. Even today, the Queen of England remains the titular head of state in both countries. During World War II, however, the European powers provided only token resistance to Japan’s invasion of much of the Pacific and its bombing of northern Australia. This European impotence began a change in the region’s political and economic orientation.  244. VETERANS REMEMBER TRAGEDY OF WAR IN PACIFIC

244. VETERANS REMEMBER TRAGEDY OF WAR IN PACIFIC

After the war, the United States, which already had a strong foothold in the Philippines, became the dominant power in the Pacific, and U.S. investment became increasingly important to the economies of Oceania. Australia and New Zealand joined the United States in a Cold War military alliance, and both fought alongside the United States in Korea and Vietnam, suffering considerable casualties and experiencing significant antiwar activity at home. U.S. cultural influences were strong, too, as North American products, technologies, movies, and pop music penetrated much of Oceania.

By the 1970s, another shift was taking place as many of the island groups were granted self-rule by their European colonizers, and Oceania became steadily drawn into the growing economies of Asia. Since the 1960s, Australia’s thriving mineral export sector has become increasingly geared toward supplying raw materials to Asian manufacturing industries (first Japan in the 1960s, and increasingly China since the 1990s). Similarly, since the 1970s, New Zealand’s wool and dairy exports have gone mostly to Asian markets. Despite occasional backlashes against “Asianization,” Australia, New Zealand, and the rest of Oceania are becoming increasingly transformed by Asian influences. Many Pacific islands have significant Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Indian minorities, and the small Asian minorities of Australia and New Zealand are increasing (see Figure 11.14F). On some Pacific islands, such as Hawaii, Asians now constitute the largest portion (42 percent in Hawaii) of the population.

606

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Oceania can be divided into four distinct indigenous cultural regions: Australia and Tasmania, settled originally by Aborigines; Melanesia, settled by Melanesians, so identified because of their skin tone derived from melanin; and Micronesia and Polynesia, settled by a variety of Austronesian peoples.

Oceania can be divided into four distinct indigenous cultural regions: Australia and Tasmania, settled originally by Aborigines; Melanesia, settled by Melanesians, so identified because of their skin tone derived from melanin; and Micronesia and Polynesia, settled by a variety of Austronesian peoples. Through colonization, Europeans were active in Oceania from the early sixteenth century until the end of World War II. During the 50 years after the war, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand were the principal powers in the Pacific.

Through colonization, Europeans were active in Oceania from the early sixteenth century until the end of World War II. During the 50 years after the war, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand were the principal powers in the Pacific. Beginning in the 1970s, Asian countries have had increasing influence throughout Oceania.

Beginning in the 1970s, Asian countries have had increasing influence throughout Oceania.