1.4 Food and Urbanization

Over time, food production has undergone many changes. It started with hunting and gathering and over the millennia evolved into more labor-intensive, small-scale, subsistence agriculture. For the vast majority of people, subsistence remained the mode of food production for many thousands of years until a series of innovations and ideas that changed the way goods were manufactured. The Industrial Revolution, broadly from 1750 to 1850, opened the door to the development of what has become modern and mechanized commercial agriculture, involving an intensive use of machinery, fuel, and chemicals. Modern processes of food production, distribution, and consumption have greatly increased the supply and, to some extent, the security of food systems. However, this has come at the cost of environmental pollution that may strain future food production and food security.

Industrial Revolution a series of innovations and ideas that occurred broadly between 1750 and 1850, which changed the way goods were manufactured

Agriculture: Early Human Impacts on the Physical Environment

Agriculture includes animal husbandry, or the raising of animals, as well as the cultivation of plants. The ability to produce food, as opposed to being dependent on hunting and gathering, led to a host of long-term changes. Human population began to grow more quickly, rates of natural resource use increased, permanent settlements eventually developed into towns and cities, and ultimately, human relationships became more formalized. Some would say these are the steps that led to civilization.

agriculture the practice of producing food through animal husbandry, or the raising of animals, and the cultivation of plants

Very early humans hunted animals and gathered plants and plant products (seeds, fruits, roots, and fibers) for their food, shelter, and clothing. To successfully use these wild resources, humans developed an extensive folk knowledge of the needs of the plants and animals they favored. The transition from hunting in the wild to tending animals in pens and pastures and from gathering wild plant products to sowing seeds and tending plants in gardens, orchards, and fields probably took place gradually over thousands of years.

Where and when did plant cultivation and animal husbandry first develop? Genetic studies support the view that at varying times between 8000 and 20,000 years ago, people in many different places around the globe independently learned to develop especially useful plants and animals through selective breeding, a process known as domestication.

domestication the process of developing plants and animals through selective breeding to live with and be of use to humans

Why did agriculture and animal husbandry develop in the first place? Certainly the desire for more secure food resources played a role, but the opportunity to trade may have been just as important. It is probably not a coincidence that many of the known locations of agricultural innovation lie along early trade routes—for example, along the Silk Road that runs through Central Asia from the eastern Mediterranean to China. In such locales, people would have had access to new information and new plants and animals brought by traders.

Agriculture and Its Consequences

Agriculture made possible the amassing of surplus stores of food for lean times, and allowed some people to specialize in activities other than food procurement. It also may have led to several developments now regarded as problems: rapid population growth, concentrated settlements where diseases could easily spread, environmental degradation, and paradoxically, malnutrition or even famine.

Through the study of human remains, archaeologists have learned that it was not uncommon for the nutritional quality of human diets to decline as people stopped eating diverse wild food species and began to eat primarily one or two species of domesticated plants and animals. Evidence of nutritional stress (shorter stature, malnourished bones and teeth) has been found repeatedly in human skeletons excavated in sites around the world where agriculture was practiced.

24

Whereas agriculture could support more people on a given piece of land than hunting and gathering, as populations expanded and as more land was turned over to agriculture, natural habitats were destroyed, reducing opportunities for hunting and gathering. Furthermore, the storage of food surpluses not only made it possible to trade food, but also made it possible for people to live together in larger concentrations, which marked the beginning of urban societies and, coincidentally, facilitated the spread of disease. Moreover, land clearing increased vulnerability to drought and other natural disasters that could wipe out an entire harvest. Thus, as ever-larger populations depended solely on cultivated food crops, episodic famine may have become more common and affected more people.

Modern Food Production and Food Security

For most of human history, people lived in subsistence economies. However, over the past five centuries of increasing global interaction and trade, people have become ever more removed from their sources of food. Today, occupational specialization means that food is increasingly mass-produced. Far fewer people work in agriculture than in the past, and now most humans work for cash to buy food and other necessities.

A side effect of this dependence on money is that the food security—the ability of a state to consistently supply a sufficient amount of basic food to the entire population—of individuals and families can be threatened by economic disruptions, even in distant places. As countries become more involved with the global economy, either they may import more food or their own food production can become vulnerable to price swings. For example, a crisis in food security began to develop in 2007 when the world price of corn spiked. Speculators in alternative energy, thinking that corn would be an ideal raw material with which to make ethanol—a substitute for gasoline—invested heavily in this commodity, creating a shortage. As a result, global corn prices rose beyond the reach of those who depended on corn as a dietary staple. Then, between the sharp price rise in oil in 2008 and the recession of 2007–2009, the global cost of basic foods rose 17 percent. When oil prices rise, all foods produced and transported with machines get more expensive.

food security the ability of a state to consistently supply a sufficient amount of basic food to the entire population

25

26

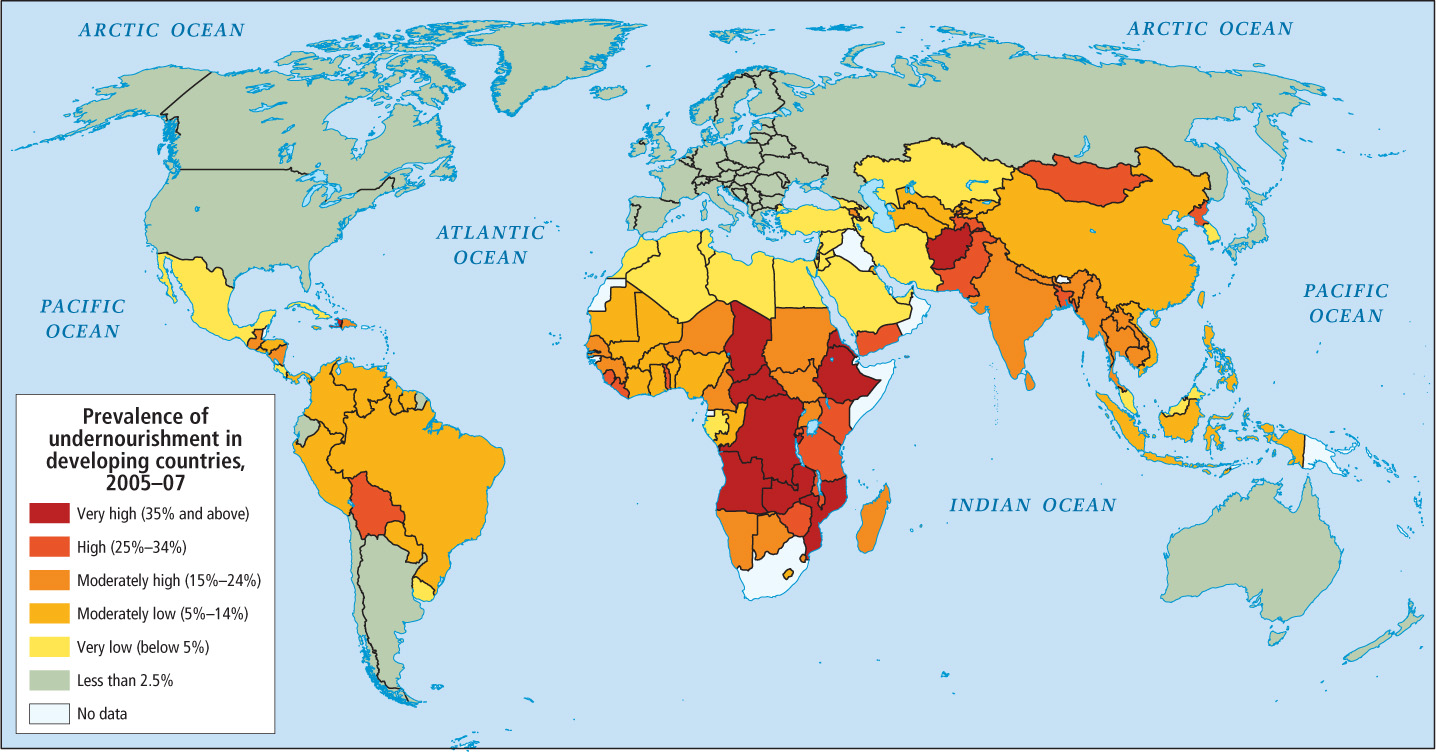

There were other contributing causes to food insecurity. When the global recession—partially caused by rising oil prices—eliminated jobs in many world locations, migrant workers could no longer send remittances to their families who then no longer had money with which to buy food. These episodes called into question the sustainability of current food production and acquisition systems. In developing countries, household economies were so ruined that parents sold important assets; went without food, to the detriment of their long-term health; and stopped sending children to school. UN statistics show real reversals of progress in human well-being in 2007–2008. Figure 1.14 identifies countries in which undernourishment is an ongoing problem and periodic food insecurity is especially intense. The situation had improved somewhat by 2012 for a few countries. See www.fao.org/hunger/en.

Another way that modernized agriculture impacts food security is through its reliance on machines, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides. Paradoxically, when the shift to this kind of agriculture was introduced in the 1970s into developing countries like India and Brazil, it was called the green revolution. In fact, the green revolution is not “green” in the modern sense of being environmentally savvy. When successfully implemented, the results of green revolution agriculture were at first spectacular: soaring production levels and high profits for those farmers who could afford the additional investment. In the early years of this movement, it seemed to scientists and developers that the world was literally getting greener. But often, poorer farmers couldn’t afford the machinery and chemicals. Also, since greatly increased production leads to lower crop prices on the market, these poorer farmers lost money. To survive, they often were forced to sell their land and move to crowded cities. Here they joined masses of urban poor whose food security was chronically precarious.

green revolution increases in food production brought about through the use of new seeds, fertilizers, mechanized equipment, irrigation, pesticides, and herbicides

Green revolution agriculture can also impact food security by damaging the environment. As rains wash fertilizers and pesticides into streams, rivers, and lakes, these bodies of water become polluted. Over time, the pollution destroys fish and other aquatic animals vital to food security. Hormones fed to farm animals to hasten growth may enter the human food chain. Soil degradation can also increase as green revolution techniques (such as mechanical plowing, tilling, and harvesting) leave soils exposed to rains that wash away natural nutrients and the soil itself. Indeed, many of the most agriculturally productive parts of North America, Europe, and Asia have already suffered moderate to serious loss of soil through erosion. Globally, soil erosion and other problems related to food production affect about 7 million square miles (2000 million hectares), putting at risk the livelihoods of a billion people.

At least in the short term, green revolution agriculture raised the maximum number of people that could be supported on a given piece of land, or its carrying capacity. However, it is unclear how sustainable these green revolution gains in food production are. In the 25 years between 1965 and 1990, total global food production rose between 70 and 135 percent (varying from region to region). In response, populations also rose quickly during this period. These successes in improving agricultural production and carrying capacities led the general public to assume that technological advances would perpetuate these increases; indeed, it is now estimated that to feed the population projected for 2050, global food output must increase by another 70 percent. Yet scientists from many disciplines estimate that within the next 50 years, environmental problems such as water scarcity and global climate change will limit, halt, or even reverse increases in food production. How can these discrepancies between expectations and realities be resolved?

27

carrying capacity the maximum number of people that a given territory can support sustainably with food, water, and other essential resources

The technological advances that could make present agricultural systems more productive are increasingly controversial. In North America, genetic modification (GM), the practice of splicing together the genes from widely divergent species to achieve particular characteristics, is increasingly being used to boost productivity. However, outside of North America, many worry about the side effects of such agricultural manipulation. Europeans have tried (unsuccessfully) to keep GM food products entirely out of Europe, fearing that they could lead to unforeseen ecological consequences or catastrophic crop failures. They point out that the main advance in GM agriculture has been the production of seeds that can tolerate high levels of environmentally damaging herbicides, such as Roundup. The use of GM crops thus could lead to more, not less, environmental degradation. Even if GM crops prove safe, in developing countries where farmers’ budgets are tiny, genetically modified seeds are much more expensive than traditional seeds. They must be purchased anew each year because GM plants do not produce viable seeds, as do plants from traditional seeds.

genetic modification (GM) in agriculture, the practice of splicing together the genes from widely divergent species to achieve particular desirable characteristics

As a result of the uncertainties of GM crops and the potential negative side effects of new agricultural technologies, many are returning to the much older idea of sustainable agriculture—farming that meets human needs without poisoning the environment or using up water and soil resources. Often these systems avoid chemical inputs entirely, as in the case of increasingly popular methods of organic agriculture. However, while these systems can be productive, they are less so than conventional green revolution systems and often require significantly more human labor, resulting in higher food prices. Increased dependence on sustainable and organic systems could therefore lead to food insecurity for some poor people, especially in cities.

sustainable agriculture farming that meets human needs without poisoning the environment or using up water and soil resources

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, one-fifth of humanity subsists on a diet too low in total calories and vital nutrients to sustain adequate health and normal physical and mental development (see Figure 1.14). As we will see in later chapters, this massive hunger problem is partly due to political instability, corruption, and inadequate distribution systems. When, for whatever reason, food is scarce, it tends to go to those who have the money to pay for it.  3. DEFORESTATION: WORLDWIDE CONCERNS

3. DEFORESTATION: WORLDWIDE CONCERNS

THINGS TO REMEMBER

While modern processes of food production and distribution have greatly increased the supply of food, environmental damage and market disruptions could strain future food production and compromise food security.

While modern processes of food production and distribution have greatly increased the supply of food, environmental damage and market disruptions could strain future food production and compromise food security. Many farmers are unable to afford the chemicals and machinery required for commercial agriculture or new, genetically modified seeds. Because their production is low, they cannot compete on price and may be forced to give up farming, often migrating to cities.

Many farmers are unable to afford the chemicals and machinery required for commercial agriculture or new, genetically modified seeds. Because their production is low, they cannot compete on price and may be forced to give up farming, often migrating to cities. Sustainable agriculture is farming that meets human needs without harming the environment or depleting water and soil resources.

Sustainable agriculture is farming that meets human needs without harming the environment or depleting water and soil resources.

1.4.1 Urbanization

In 1700, fewer than 7 million people, or just 10 percent of the world’s total population, lived in cities, and only 5 cities had populations of several hundred thousand people or more. The world we live in today has been transformed by urbanization, the process whereby cities, towns, and suburbs grow as populations shift from rural to urban livelihoods. Now a little over half of the world’s population lives in cities, and there are more than 400 cities of more than 1 million.

urbanization the process whereby cities, towns, and suburbs grow as populations shift from rural to urban livelihoods

Why Are Cities Growing?

Geographic Insight 4

Food and Urbanization: Modernization in food production is pushing agricultural workers out of rural areas toward urban areas where jobs are more plentiful but where food must be purchased. This circumstance often leads to dependency on imported food.

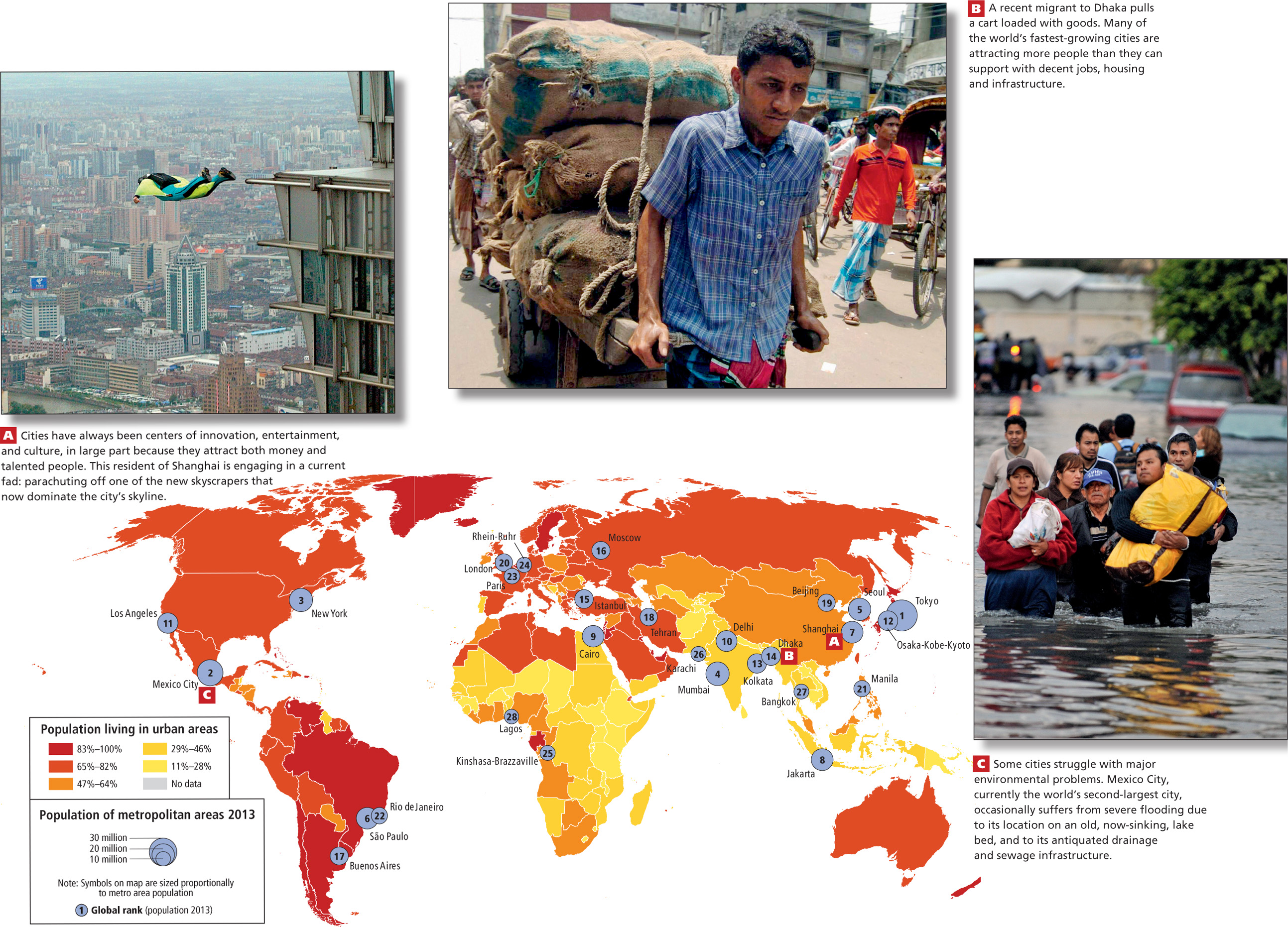

For some time, economic changes, such as the mechanization of food production that has drastically reduced the need for labor while greatly increasing the food supply, have been pushing people out of rural areas, while the development of manufacturing and service economies and the possibility of earning cash incomes have been pulling them into cities. This process is called the push/pull phenomenon of urbanization. Numerous cities, especially in poorer parts of the world, have been unprepared for the massive inflow of rural migrants, many of whom now live in polluted slum areas plagued by natural and human-made hazards, poor housing, and inadequate access to food, clean water, education, and social services (see Figure 1.15C). Often a substantial portion of the migrants’ cash income goes to support their still-rural families (see Figure 1.15B).

push/pull phenomenon of urbanization conditions, such as political instability or economic changes, that encourage (push) people to leave rural areas, and urban factors, such as job opportunities, that encourage (pull) people to move to urban areas

slum densely populated area characterized by crowding, run-down housing, and inadequate access to food, clean water, education, and social services

Thinking Geographically

After you have read about urbanization, you will be able to answer the following questions:

Question

XM7a98oCAZN0lDgtMPd0C0BdpbbAB1jKcVD1J0KxEKwiSx+FU/8LEEBzTz3ZxGNEb3rL5P1PKw4vw1qqJrchSTRFamwO2VR4kD0QycNo9cAcCNqXUY2ZfHTrkjOLNjhrKKNAuOBaQLUdkCzGRhhszI40Y6uCIGjkX2NQkiOI7v96ecQOgeI4vWnCOK7ocX65+inm8DUhPzpGdbnwT/ZxxfpX3OPMdV7/tRmq9PWCZUS0CWDuQNKbqR8rcVC0GKGVBrYYkM9PUcFAzQaxmp19BBwBNRJUeg6z4Nlasmk7jcgjx6xqGEnjx9nItEAwnhtzt3tmlFQJeFcSvg2SB73ax3yLUpROP+wS7M/jYjphkUEJLo23XAjKO8VVBJkWeBaYMpw+1HImfn5r3xpSA0y+gdZyfPItx6WT1uQp9tBLeMZvOR715Aon5QI/27KbcMt0JylnldbOEz6YoNvk8dZd4A==

Question

p51JUeNVRu1PcAPWX+KOIdTP/NiWJ9JF+C3otJc+zHTFqi6xCXyIS22+zGIuuQw9PpcF7mM+P9ktdJ1mdMsM0FV6f0jA9xB+q+zEq/DGNxgfoJDlYdfhtvDKpJUriFFx/kUTXHz5i3hpz7ACZKVbItye8cb5jLgby19yYiR0sIslCxSF0O+7JcUP0tzp0TWRghKacF72L3XOskbidyaVuBKG6lm05wPAySNEshQ0JfRz7X0agLpSNXw36fw5N1SJUJkXzI2PPPH+assad26I7VaWNCRDIMw1jrIpE/dasKwmm4IuGw8vj65Y51SSXcOUO4su+NUhZfBQNIw7ebSBYcYIziBXj0h/

Question

KFj4JrEv/Vcg63+ty4JsX6cxGLTg7Rr4FTXuiRyeNeBW4X7wimWuCc+wCerUgpFX2EyHXqTCGx+SIe4UsLNqJIceG2fXWg7Br6//5OGdDuXdQQmv/Jevs/xopvbQtmgCWjGP8LkWXvjH4CitZ4wuRV+gWLk24cV/Zhq8SwCBX1GdO2XxL8uJdwW4BDooM2QpC9DpNPtjW5BEmrs9HHfNyiOCz1yRaEfLcxgOoMNFAW17gKUrFrJc5MC6WhuQIzb4LbwaWVwQ+mQmhsg9I9Mc/08j5el5yu9XxBGv6AT6VORURl6qdSmOY+wM5G0ZunqsYiig9nfHQ9RMUB2ExNNweHQNjW/CGWtPEgsuKU+02TUkU5DKm9E8XP4jsjhmZQQVLwQa2X9sfLc0YBnsV3tRf0kMJIH9h4dMTzuZF6A9iTThWL6m2/eEacjnHTX9pqCnq38XbMjLC+0=

28

Patterns of Urban Growth

The most rapidly growing cities are in developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Middle and South America. The settlement pattern of these cities bears witness to their rapid and often unplanned growth, fueled in part by the steady arrival of masses of poor rural people looking for work. Cities like Mumbai (in India), Cairo (in Egypt), Nairobi (in Kenya), and Rio de Janeiro (in Brazil) sprawl out from a small affluent core, often the oldest part, where there are upscale businesses, fine old buildings, banks, shopping centers, and residences for wealthy people. Surrounding these elite landscapes are sprawling mixed commercial, industrial, and middle-class residential areas, interspersed with pockets of extremely dense slums. Also known as barrios, favelas, hutments, shantytowns, ghettos, and tent villages, these settlements provide housing for the poorest of the poor, who provide low-wage labor for the city (see Figure 1.15B). Housing is often self-built out of any materials the residents can find: cardboard, corrugated metal, masonry, and scraps of wood and plastic. There are usually no building codes, no toilets with sewer connections, and no clean water; electricity is often obtained from illegal and dangerous connections to nearby power lines. Schools are few and overcrowded, and transportation is provided only by informal, nonscheduled van-based services. Because these slums can pop up on scraps of vacant land virtually overnight, an overflow of people, often unflatteringly called squatters, may soon be living in unhealthy conditions. The workers who labor to build soaring modern skyscrapers in one part of a city may find that they have to sleep on the street or in a hovel with no water or plumbing just a few blocks away.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Urban Migrant Success Stories

Slums are only part of the story of urbanization today. Those who are financially able to come to urban areas for education and complete their studies tend to find employment in modern industries and business services. They constitute the new middle class and leave their imprint on urban landscapes via the high-rise apartments they occupy and the shops and entertainment facilities they frequent (see Figure 1.15 map, A). Cities such as Mumbai in India, São Paulo in Brazil, Cape Town in South Africa, and Shanghai in China are now home to this more educated group of new urban residents, many of whom may have started life on farms and in villages.

In the past, most migrants in cities were young males, but increasingly they are young females. Cities offer women more than better-paying jobs. They also provide access to education, better health care, and more personal freedom.

The UN estimates that currently over a billion people live in urban slums, with that number to increase to 2 billion by 2030. Life in these areas can be insecure and chaotic as criminal gangs often assert control through violence and looting—all actions that are especially likely during periods of economic recession and political instability.

29

30

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Today about half of the world’s population live in cities; there are over 400 cities with more than 1 million people and about 28 cities of more than 10 million people.

Today about half of the world’s population live in cities; there are over 400 cities with more than 1 million people and about 28 cities of more than 10 million people. _div_Geographic Insight 4_enddiv_Food and Urbanization Changes in agriculture and food production are pushing people out of rural areas, while the development of manufacturing and service economies is pulling them into cities.

_div_Geographic Insight 4_enddiv_Food and Urbanization Changes in agriculture and food production are pushing people out of rural areas, while the development of manufacturing and service economies is pulling them into cities. For some, urbanization means improved living standards, while for others it means being forced into slums with inadequate food, water, and social services.

For some, urbanization means improved living standards, while for others it means being forced into slums with inadequate food, water, and social services.