The Old Economic Core

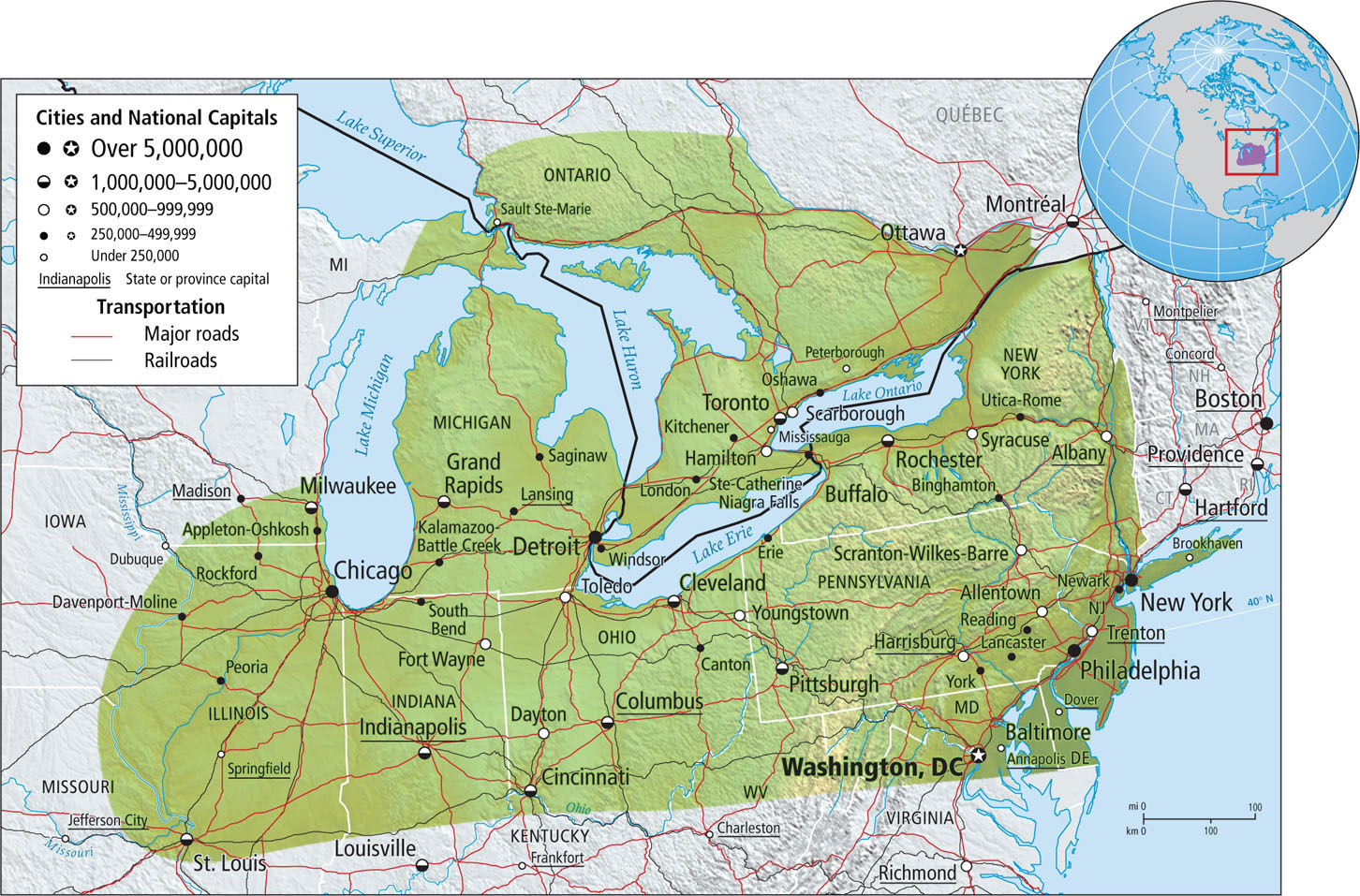

The area that includes southern Ontario and the north-central part of the United States, from Illinois to New York (Figure 2.42), represents less than 5 percent of the total land area of the United States and Canada, but it was once the economic core of North America. As recently as 1975, its industries produced more than 70 percent of the continent’s steel and a similar percentage of its motor vehicles and parts, an output made possible by the availability of energy and mineral resources in the region or just beyond its boundaries. Today, the industrial economy of this region has gone into severe decline, and large cities dependent on manufacturing, such as Detroit and Cleveland, and hundreds of smaller cities and towns, have suffered near economic collapse. Meanwhile, some of the region’s largest cities, such as New York, Toronto, and Chicago, continue to prosper, largely because of their strong service industries, which connect them to regional and global economies.

110

Loss of Economic Dominance

Plants started closing in the 1970s, and by the 1990s, most manufacturing jobs had moved outside the old industrial heartland to the South, Middle West, Pacific Northwest, and abroad. Industrial resources for factories now come from elsewhere: coal is mined in Wyoming, British Columbia, Alberta, and Appalachia; steel, the mainstay of the automotive and construction industries, can be more cheaply derived from scrap metal or purchased abroad from Brazil, Japan, or Europe.

The trend of industrial shutdowns worsened with the closing of auto plants in Detroit in 2009; between 2000 and 2010, Detroit’s population plunged 25 percent. Large, outdated factories and some public buildings (Figure 2.43) now sit empty or underused throughout much of the economic core, which some people refer to as the Rust Belt.

The Impact of the Economic Decline on People

After World War II, industrial jobs drew millions of rural men and women, both black and white, from the South to the industrial core. Many of their sons and daughters, now without work and without funds to retrain or relocate, constitute some of the more than 46.7 million U.S. citizens living in poverty as of 2010. Consider the case of one inner-city neighborhood on the west side of Chicago, called North Lawndale, which has had repeated massive job losses.

In 1960, there were 125,000 people living in North Lawndale, with two large factories employing 57,000 workers, and a large retail chain’s corporate headquarters supporting thousands of secretaries and office workers. One by one, the employers closed their doors, and by the 1980s North Lawndale was disintegrating. The housing stock deteriorated as families and businesses left to look for opportunities elsewhere. By 2003, North Lawndale had shrunk to just 50,000 people, and over 50 percent of the adults were unemployed. The North Lawndale Industrial Development Team, with the help of a family foundation and local civic groups, still actively recruits industry and offers to provide a custom-trained labor force.

Despite the importance of industry in this region, it would be wrong to think of the economic core as solely grounded on factories and mines. In between the great industrial cities of this region are thousands of acres of some of the best temperate-climate farmland in North America. And as during its industrial heyday, the thousands of miles of shoreland around the Great Lakes and oceanfront along the Eastern Seaboard provide both winter and summer recreational landscapes, as do the mountains of New York State and Pennsylvania. These ancillary economic activities constitute an important source of supplementary employment for families devastated by factory closings.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The old economic core was once the heart of industrial production in North America.

The old economic core was once the heart of industrial production in North America. The loss of millions of manufacturing jobs in this subregion has had serious social consequences.

The loss of millions of manufacturing jobs in this subregion has had serious social consequences. Changes in the production of steel and in energy costs, plus the loss of industry to foreign sites, brought on a major decline in the old economic core.

Changes in the production of steel and in energy costs, plus the loss of industry to foreign sites, brought on a major decline in the old economic core.