Central America

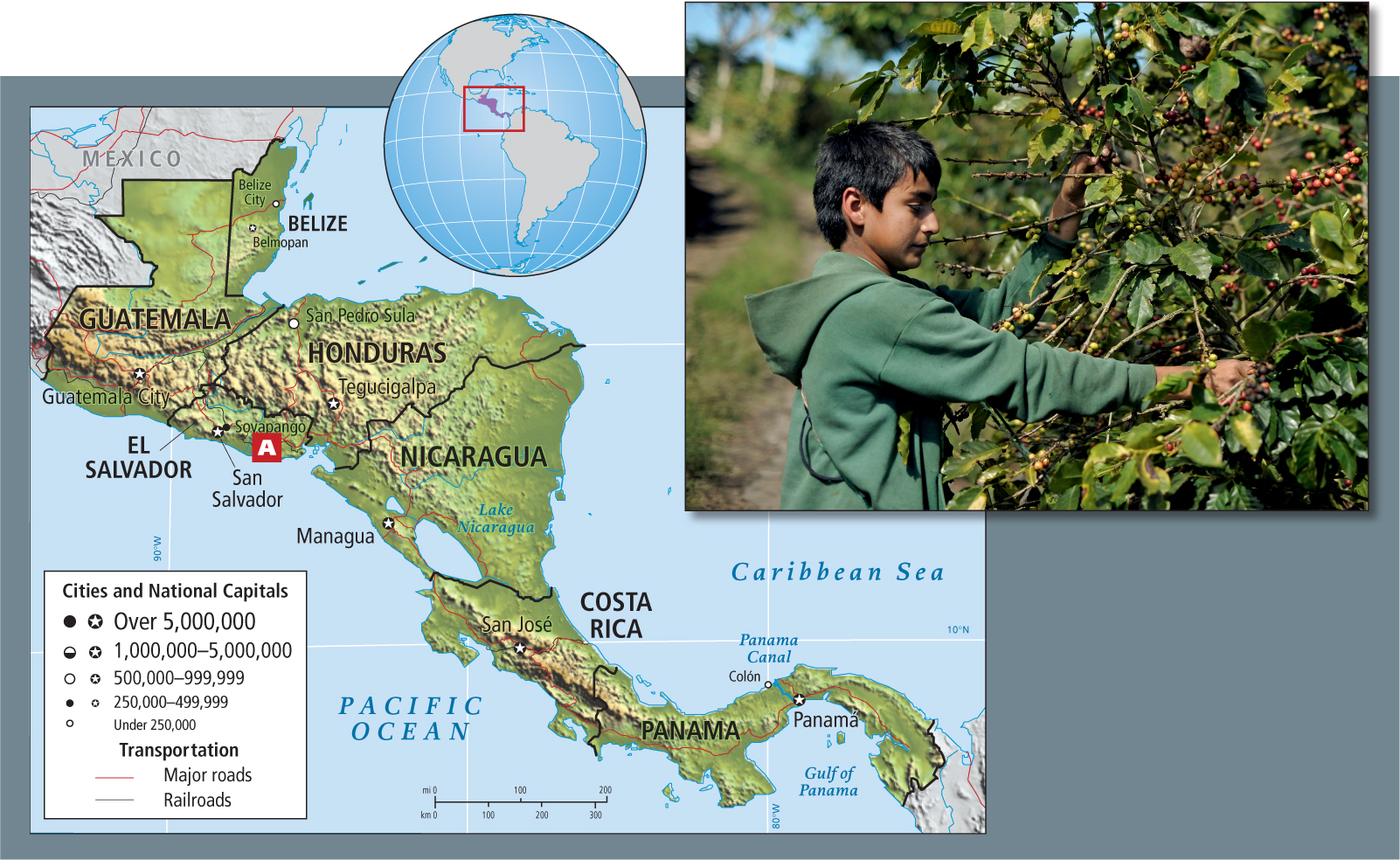

Central America’s wealth is in its soil. Although industry and services account for increasing proportions of the gross domestic product of all countries, fully one-third of the people of the seven countries of Central America (Figure 3.32) remain dependent on the production of their plantations, ranches, and small farms, minifundios (Figure 3.33; see also Figure 3.32A). The income disparity in the region is primarily the result of the fact that most of the land is controlled by a tiny minority of wealthy individuals and companies.

Most of the Central American isthmus consists of three physical zones that are not well connected with each other: the narrow Pacific coast; the highland interior; and the long, sloping, rain-washed Caribbean coastal region. Along the Pacific coast, mestizo (ladino is the local term) laborers work on large plantations that grow sugarcane, cotton, and bananas and other tropical fruits; coffee is grown in the hills behind the coast. In the highland interior of Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, cattle ranching and commercial agriculture have recently displaced indigenous subsistence farmers. Similarly, the humid Caribbean coastal region, long sparsely populated with indigenous and African-Caribbean subsistence farmers, is increasingly dominated by commercial agriculture, forestry, tourism development, and resettlement projects for small farmers displaced from the highlands.

ladino a local term for mestizo, used in Central America

Social and Economic Conditions

In Central America, the majority of people are either indigenous or ladino, and about half still live in small rural villages surrounded by tiny plots of land called minifundios (see Figure 3.33). In these villages most people make a sparse living by cultivating their own food and cash crops on their own minifundios; by working land they rent as sharecroppers; or by working as seasonal laborers on large farms and plantations (see the story of Aguilar Busto Rosalino in the vignette). The people of this region have experienced centuries of hardship, including long hours of labor at low wages and the loss of most of their farmlands to large landholders. In both rural and urban areas, infrastructure development has lagged. Roads are primitive and few. Most people lack clean water, sanitation, health care, protection from poisoning by agricultural chemicals, and basic education. Often they do not have access to enough arable land to meet their basic needs. The majority of the land is held in huge tracts—ranches, plantations, and haciendas—owned by a few families. As a result, on the small bits of farmland available to the poor for growing their own food and cash crops, local densities may be 1000 people or more per square mile. These circumstances all affect the well-being of the people, as reflected in Figure 3.22).

173

The poverty of the majority is largely the result not of overpopulation but rather of the control of land by a few rich landholders. Only tiny El Salvador is truly densely populated, with an average of 767 people per square mile (296 per square kilometer) (Table 3.3). In fact, arable land there is so scarce that people have slipped over the border to cultivate land in Honduras. Today there are more Salvadorans living abroad than in El Salvador!

| Country (ordered by size) | Population | Population density per square mile (kilometer) | Rate of natural increase (percent) | Literacy rate (percent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 114,800,000 | 59 (153) | 1.4 | 93.4 |

| Guatemala | 14,000,000 | 135 (350) | 2.4 | 74.5 |

| Honduras | 7,500,000 | 69 (179) | 2.4 | 83.6 |

| El Salvador | 7,300,000 | 296 (767) | 1.1 | 84.1 |

| Nicaragua | 5,700,000 | 45 (117) | 1.9 | 78 |

| Costa Rica | 4,500,000 | 92 (238) | 1.2 | 96 |

| Panama | 3,500,000 | 47 (122) | 1.4 | 93.6 |

| Belize | 300,000 | 14 (36) | 2.1 | 75.1 (2009) |

| Sources: Population Reference Bureau, 2011 World Population Data Sheet; and United Nations Human Development Report 2011 (New York: United Nations Development Programme), Table 9. | ||||

The Exceptions: Costa Rica and Panama

Two exceptions to these extreme patterns of elite monopoly, mass poverty, and rapid population growth are Costa Rica, and to some extent, Panama (see Figure 3.22 and Table 3.3). The huge disparities in wealth between colonists and laborers did not develop in Costa Rica, chiefly because there were no precious metals to extract and the fairly small native population died out soon after the conquest. Without a captive labor supply, the European immigrants to Costa Rica set up small but productive family farms that they worked themselves, not unlike early North American family farms. Costa Rica has democratic traditions that stretch back to the nineteenth century, and it has unusually enlightened elected officials as well as one of the region’s soundest economies. Population growth is low for the region, at 1.3 percent per year, and investment in human capital—in schools, health care, social services, and infrastructure—has been high. With no standing army, the country spends little on nonproductive military installations. As a result, Costa Rica has Central America’s highest literacy rates, and on many scales of comparison, including GDP per capita and HDI, the country stands out for its high living standards (see Figure 3.22). Costa Rica has often been hailed as a beacon for the more troubled nations of Central America.

174

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

A Role Model

Costa Rica is a relatively affluent, healthy, and well-educated society—and an innovator in environmental activism. As a successful democracy, it serves as an important role model for future development in Central America.

Panama is known primarily for the canal that joins the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea with the Pacific, precluding the long sea voyage around the tip of South America. But the canal is no longer large enough to accommodate the huge cargo, tanker, and cruise ships of the modern era, and it has become a bottleneck for world trade. Opened in 1914, the Panama Canal was built primarily with money from the United States and labor from the British Caribbean. Initially, the United States managed the canal and maintained a large military presence there; as a result, Panama remained a virtual colony of the United States. In 1999, the United States turned over the canal to Panama and removed itself as a dominant presence. Interestingly, the turnover of the canal came at a time when it was not only obsolete but facing competition from nearby oil and gas pipelines and potentially from another canal route through Nicaragua. In October of 2006, Panamanians overwhelmingly approved a U.S.$5.25 billion project to widen the canal and make it usable by mega-ships of the future. The new canal lanes and locks are expected to be completed in 2014.  59. VOTERS IN PANAMA APPROVE MAJOR EXPANSION OF CANAL

59. VOTERS IN PANAMA APPROVE MAJOR EXPANSION OF CANAL

Panama became a center for residential tourism investment by North American and European firms in the 1990s, and by 2008, dozens of high- and medium-rise condominium projects were transforming the urban landscapes, nearly all meant for seasonal occupation by outsiders. However, the mortgage crisis that began in late 2008 has left many of these projects halted in mid-construction.

Environmental Concerns in Central America

Farmers often use unwise practices to wrench from their tiny plots of land enough food to feed their families. As a result, the news media often blame them for environmental degradation. However, most environmental problems in Central America are caused not by the practices of small farmers but rather by large-scale agriculture and cattle ranching. In Honduras, the reservoir for a large hydroelectric dam built only a few years ago has been nearly filled with silt eroded from surrounding cleared land. Its electricity output must now be supplemented with generators run on imported oil.

Costa Rica has been a leader in the environmental movement in Central America. In the 1980s, the country established wetland parks along the Caribbean coast and encouraged ecotourism at a number of nature preserves, while at the same time acknowledging the potentially negative environmental side effects of tourism. Costa Rica supports scientific research through several international study centers in its central highlands and lowland rain forests, where students from throughout the hemisphere study tropical environments. Elsewhere in Central America, support for national parks is growing. With the help of the U.S. National Park Service and international NGOs such as the Nature Conservancy and the Audubon Society, 175 small parks have been established in the subregion.

Decades of Civil Conflict

Frustrated with governments unresponsive to their extreme plight, indigenous people and other rural people in Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador began organizing protest movements in the 1970s. In some cases, they had the help of liberation theology advocates and Marxist revolutionaries. Despite reasonable requests for moderate reforms, they were met with stiff resistance from wealthy elites assisted by national military forces. Brutal civil wars have plagued these countries over recent decades.

In the 1980s, protests were particularly strong in Guatemala, which has the largest indigenous population in Central America. During those dying days of the Cold War, the United States backed and armed military dictatorships (General Ríos Montt, in the case of Guatemala) because it was convinced that the revolutionaries posed a Communist-inspired threat to the United States. National army death squads killed many thousands of native protesters with guns and equipment supplied by the United States and drove 150,000 into exile in Mexico. In time, the protesters responded with guerrilla tactics. Rigoberta Menchú, an indigenous Guatemalan woman, won the 1992 Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts to stop government violence against her people. Her autobiographical account attracted public attention to the carnage and was important in awakening worldwide concern. Eventually, after a number of regional peacemakers joined Menchú in bringing international pressure to bear on the Guatemalan government, the Guatemalan Peace Accord was signed in September 1996.

Since 2002, Central American rural grassroots resistance has been directed against the globalization of markets across the region. Central American farmers see both the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), which would extend many of the provisions of NAFTA to the entire hemisphere, and the Central American Free Trade Association (CAFTA) as threats to their survival. For example, Oxfam, an international NGO concerned with issues of hunger and human rights, estimates that under the free market rules of CAFTA, U.S. exports of its mass-produced corn to Central America would increase 1000 percent in just 1 year. Such a volume of corn would lower the market price to the point where local farmers would be squeezed out of corn production and would probably have to migrate to find work. Although CAFTA was finally implemented in January 2009, economists generally agree that it is impossible to assess the effects of CAFTA in the short term because of the general downturn caused by the global recession. Both imports and exports in the CAFTA zone were down during its first year.

175

A Case Study of Civil Conflict: Nicaragua

Until the late twentieth century, Nicaragua showed landownership patterns characteristic of the region: a tiny elite held the usual monopoly on land, while the mass of laborers lived in poverty. By 1910, the American company United Fruit held coffee and fruit plantations in the Nicaraguan Pacific uplands and on the Pacific coastal plain. Between 1912 and 1933, the United States kept marines in Nicaragua to quell labor protests that threatened U.S. interests in Nicaragua’s food export economy. This U.S. military support helped the wealthy Somoza family to establish its members as brutal dictators in Nicaragua in the 1930s.

The Marxist-leaning Sandinista revolution of 1979 finally ousted the Somoza regime. The Sandinistas, who eventually won several national elections, embarked on a program of land and agricultural reform and improved basic education and health services. Soon, however, a debilitating war with the Contras, who were right-wing counterinsurgents backed by local elites, undid most of the social progress achieved by the Sandinistas. Again, the United States was involved. In what became known as the Iran–Contra affair, the Communist-wary Reagan administration secretly supported the Contras (which Congress had explicitly denied funds for) with money from covert arms sales to Iran. A trade embargo imposed by the United States further contributed to the ruin of the Nicaraguan economy. By the end of the 1980s, Nicaragua was one of the poorest nations in the Western Hemisphere.

In national elections in 1990, an electorate weary of violence defeated the Sandinistas. Starting in 1997, several free elections, in which 75 percent of the eligible citizens voted, resulted in moderate governments that continued to find it difficult to bring Nicaragua any measure of prosperity. In 2011, Daniel Ortega, once a Sandinista leader and president in the late 1980s, was elected president for a third term. He takes populist and anti-U.S. positions similar to those once taken by Chávez in Venezuela and the Castros in Cuba, but he also makes overtures to foreign investors.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Behind much of the civil disorder and violence in Central American countries lay persistent disparity of wealth and a long-standing unwillingness to invest in human capital by providing education and social services.

Behind much of the civil disorder and violence in Central American countries lay persistent disparity of wealth and a long-standing unwillingness to invest in human capital by providing education and social services. Costa Rica is an exception to the pattern of civil disorder and control by elites in the subregion.

Costa Rica is an exception to the pattern of civil disorder and control by elites in the subregion. Although participatory democracy is growing, a tiny minority of elites and the military continue to control political and economic power, often in collusion with foreign businesses and governments (including that of the United States). The result has been interminable bloody conflicts that have killed thousands and seriously inhibited development.

Although participatory democracy is growing, a tiny minority of elites and the military continue to control political and economic power, often in collusion with foreign businesses and governments (including that of the United States). The result has been interminable bloody conflicts that have killed thousands and seriously inhibited development.