Economic and Political Issues

At the end of World War II, European leaders concluded that the best way to prevent the kind of hostilities that had led to two world wars would be to forge closer economic ties among the European nation-states. Over the next 50 years, a series of steps were taken that gradually united Europe economically and socially. More recently, tentative attempts at political unification have also been made, primarily for foreign affairs purposes.

Steps in Creating the European Union

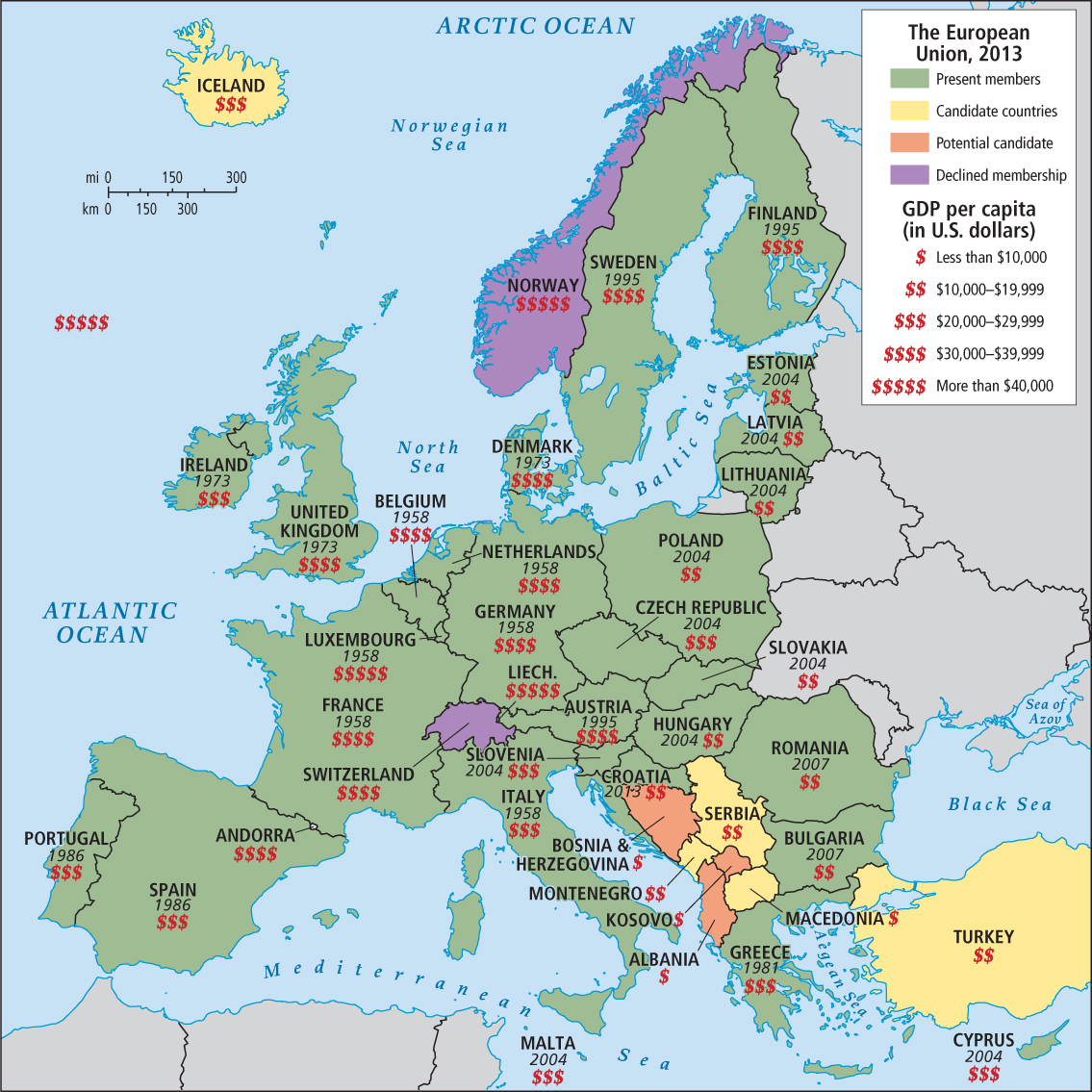

The first step toward developing an economic union in Europe began in 1951 with the creation of a common market for coal and steel (two resources essential for war industries) that, in the rebuilding of Europe, enabled the monitoring of Germany’s industrial rehabilitation. The next major step took place in 1958, when Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, France, Italy, and West Germany formed the European Economic Community (EEC). The members of the EEC agreed to eliminate certain tariffs against one another and to promote mutual trade and cooperation. Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom joined in 1973; Greece, Spain, and Portugal in the 1980s; and Austria, Finland, and Sweden in 1995, bringing the total number of member countries to 15. In 1992, the EEC became the European Union, with the intent to work toward a level of economic and social integration that would make possible the free flow of goods and people across national borders. The goal of eventually having sufficient social integration to make the borders truly open clarified the EU’s ambitions as broader than merely achieving an economic union.

After the demise and fall of the Soviet Union, the European Union expanded into Central Europe. As early as the 1980s, Soviet control over Central Europe began to falter in the face of a workers’ rebellion in Poland, known as Solidarity. By 1990, East Germany was reuniting with West Germany. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought on the collapse of many economic and political relationships in Central Europe. Thousands of workers lost their jobs. In some of the poorest countries, such as Romania, Bulgaria, and Serbia, social turmoil and organized crime threatened stability. Membership in the European Union became especially attractive to Central European political leaders and citizens who thought it would spur economic development for them that would be a result of investment by wealthier EU member countries from West and North Europe.  90. POLES CELEBRATE THE 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF SOLIDARITY

90. POLES CELEBRATE THE 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF SOLIDARITY

Standards for EU membership, however, are rather demanding and specific. A country must have both political stability and a democratically elected government. Each country has to adjust its constitution to EU standards that guarantee the rule of law, human rights, and respect for minorities. Each must also have a functioning market economy that is open to investment by foreign-owned companies and that has well-controlled banks. Finally, farms and industries must comply with strict regulations governing the finest details of their products and the health of environments. Meeting these requirements has been a challenge for members such as Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary.

Two very wealthy countries have chosen not to join the European Union: Switzerland and Norway. They, plus Iceland, have long treasured their neutral role in world politics. Moreover, they have been concerned about losing control over their domestic economic affairs. Iceland has now applied to join the European Union, primarily for financial security. During the recession that in Europe began in 2008–2009, Iceland lost enormous wealth due in large part to banking speculation in foreign markets; it also became highly indebted to the International Monetary Fund. Iceland is currently what is called a “candidate” EU country (Figure 4.14).

Croatia, in southeastern Europe, is likely to be the next country to join the European Union. Several countries on the perimeter of Europe are candidate EU countries. In addition to Iceland, they include Turkey, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia. The likelihood of Turkey joining vacillates. Turkey has strained relations with the island country of Cyprus (which was admitted to the European Union in 2004, but due to financial problems may not remain), and Turkey has a history of human rights violations against minorities (especially against its large Kurdish population). There are also some issues regarding the separation of religion and the state; Turkey would be the first majority Muslim country to join the European Union. Turkey itself has some reservations. Its political advantage may lie not in Europe but as a leader in the Middle East, where, since the revolutions collectively referred to as the Arab Spring and during the crisis in Syria (see Chapter 6, page 298), Turkey has been a voice of calm and reason. A few other countries—Ukraine, Moldova, and perhaps even the Caucasian republics (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia)—may at some time be invited to join. However, there is strong opposition to this within Europe, and Europe’s huge and potentially powerful neighbor, Russia, opposes the expansion of the European Union into what it regards as its sphere of influence.  93. EU TELLS TURKEY TO DEEPEN REFORMS

93. EU TELLS TURKEY TO DEEPEN REFORMS

EU Governing InstitutionsSomewhat similar to the United States, the European Union has one executive branch and two legislative bodies. The European Commission acts like an executive branch of government, proposing new laws and implementing decisions. Each of the 28 member states gets one commissioner, who is appointed for a 5-year term, subject to the approval of the European Parliament; but after 2014, the size of the Commission will be reduced to 18, with the right to appoint rotating commissioners. Commissioners are expected to uphold common interests and not those of their own countries. The entire Commission must resign if censured by Parliament. The European Commission also includes about 25,000 civil servants who work in Brussels to administer the European Union on a day-to-day basis.

211

EU citizens directly elect the European Parliament, with each country electing a proportion of seats based on its population, much like the U.S. House of Representatives. The Parliament elects the president of the European Commission, who serves for 2½ years as a head of state and head of foreign policy. Laws must be passed in Parliament by 55 percent of the member states, which must contain 65 percent of the EU total population. In other words, a simple majority does not rule. The Council of the European Union is similar to the U.S. Senate in that it is the more powerful of the two legislative bodies. However, its members are not elected but consist of one minister of government from each EU country.

Economic Integration and a Common Currency

economies of scale reductions in the unit cost of production that occur when goods or services are efficiently mass produced, resulting in increased profits per unit

Economic integration has solved a number of problems in Europe. Individual European countries have far smaller populations than their competitors in North America and Asia. This means that they have smaller internal markets for their products, so their companies earn lower profits than those in large countries. The European Union solved this problem by joining European national economies into a common market. Companies in any EU country now have access to a much larger market and can potentially make larger profits through economies of scale (reductions in the unit costs of production that occur when goods or services are efficiently mass produced, resulting in increased profits per unit). Before the European Union, when businesses sold their products to neighboring countries, their earnings were diminished by tariffs and other regulations, as well as by fees for currency exchanges.

212

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The Nobel Peace Prize

Europe’s long history of democracy has facilitated the healing of wounds. After both world wars, high levels of social and economic development have helped the countries of the region work cooperatively with each other to create and maintain the European Union. This accomplishment was recognized in October of 2012 with the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to the whole of the European Union, a prize that normally goes to an individual.

euro the official (but not required) currency of the European Union as of January 1999

The official currency of the European Union is the euro (€). Seventeen EU countries now use the euro: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. Countries that use the euro have a greater voice in the creation of EU economic policies, and the use of a common currency greatly facilitates trade, travel, and migration within the European Union. All non-euro member states, except Sweden and the United Kingdom, have currencies whose value is determined by that of the euro. Depending on global financial conditions, either the euro or the U.S. dollar is the preferred currency of international trade and finance.

Economic Comparisons of the European Union and the United StatesThe EU economy now encompasses over 500 million people (out of a total of 540 million in the whole of Europe)—roughly 200 million more than live in the United States. Collectively, the EU countries are wealthy. In 2011, their joint economy was $15.65 trillion (PPP), about 2 percent larger than that of the United States, making the European Union the largest economy in the world. Furthermore, trade within the European Union amounts to about twice the monetary value of trade with the outside world.

In contrast to the United States, which usually imports far more than it exports—resulting in a trade deficit—the European Union often has maintained a trade balance in which the values of imports and exports are roughly equal. In terms of income, according to the World Bank, the average 2011 GNI per capita (PPP) for the European Union ($33,982) was significantly less than that of the United States ($48,450), although the disparity of wealth in the European Union was also lower by about one-third than in the United States, resulting in lower levels of poverty in the EU.

Careful regulation of EU economies results in generally slower economic growth than in the United States. Until the recent debt crises, these regulations made the European Union more resilient to global financial crises, such as the crisis beginning in 2008, largely due to stronger control (than in the United States) of the banking industry and financial markets.

Some Europeans believe that the European Union, which is already a global economic power, should become a global counterforce to the United States in political and military affairs. For this to happen, European countries would have to give up some political and financial sovereignty so that foreign policy could be initiated at the supranational or federal level.

The Euro and Debt Crises

In recent years, there have been major challenges to the euro, most significantly in the form of a debt crisis that has tested the traditional mechanisms that governments use to maintain economic stability. The debt crisis first emerged in Greece, where the fact that government spending was greatly outpacing tax revenues was disguised in official reports to the European Union. Also, Greece’s trade deficit grew to unsustainable levels in part because of the global economic slowdown starting (in Europe) in 2008, which affected tourism and reduced demand for Greece’s exports. Normally, governments respond to high levels of debt by borrowing from other countries and then reducing the value of their currency, relative to that of the lenders, which makes these debts easier to pay. However, this was not an option for any member of the Euro zone because no country could, by itself, manipulate the value of the euro. The EU’s main lenders included Germany, France, banks across Europe and Asia, and the International Money Fund (IMF), as well as many Greek banks. Hindsight shows that none of these banks was thorough enough in researching the Greek financial situation. The fact that there is no European central bank with regulatory authority made it difficult to control the crisis. When Greece was revealed to be unable to repay its loans, the economies of other Euro zone countries in similar debt circumstances (such as Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Slovenia) also began to falter as international investors started to pull their funding out.

In response to these crises, the European Union developed mechanisms to limit government debt in all countries that use the euro. However, as of 2013, the potential for currency and debt crises remains. Among the possible solutions are increasing the political and financial ties between EU countries so that economic policies could be hammered out and enforced at the federal level, and the creation of a central bank. However, many Euro zone countries, even those in financial difficulty—such as Greece, Cyprus, and Slovenia—strenuously object to giving EU institutions more control over their financial affairs.

The European Union, Globalization, and DevelopmentThe European Union pursues a number of economic development strategies designed to ensure its ability to compete with the United States, Japan, and the developing economies of Asia, Africa, and South America. To increase Europe’s export potential, the EU has focused on lowering the cost of producing goods in Europe. One strategy is to shift labor-intensive industries from the wealthiest EU countries in western Europe, where wages are high, to the relatively poorer, lower-wage member states of Central Europe (see Figure 4.14). This strategy has generally worked well, helping poorer European countries prosper while keeping the costs of doing business low enough to restrain European companies from moving away from Europe to places where costs are lower still. However, while the economies of Central Europe have grown, in Europe’s wealthiest countries the resultant reduction of industrial capacity (deindustrialization) has led to higher unemployment. And despite these efforts, some EU firms have moved abroad to cut costs.

213

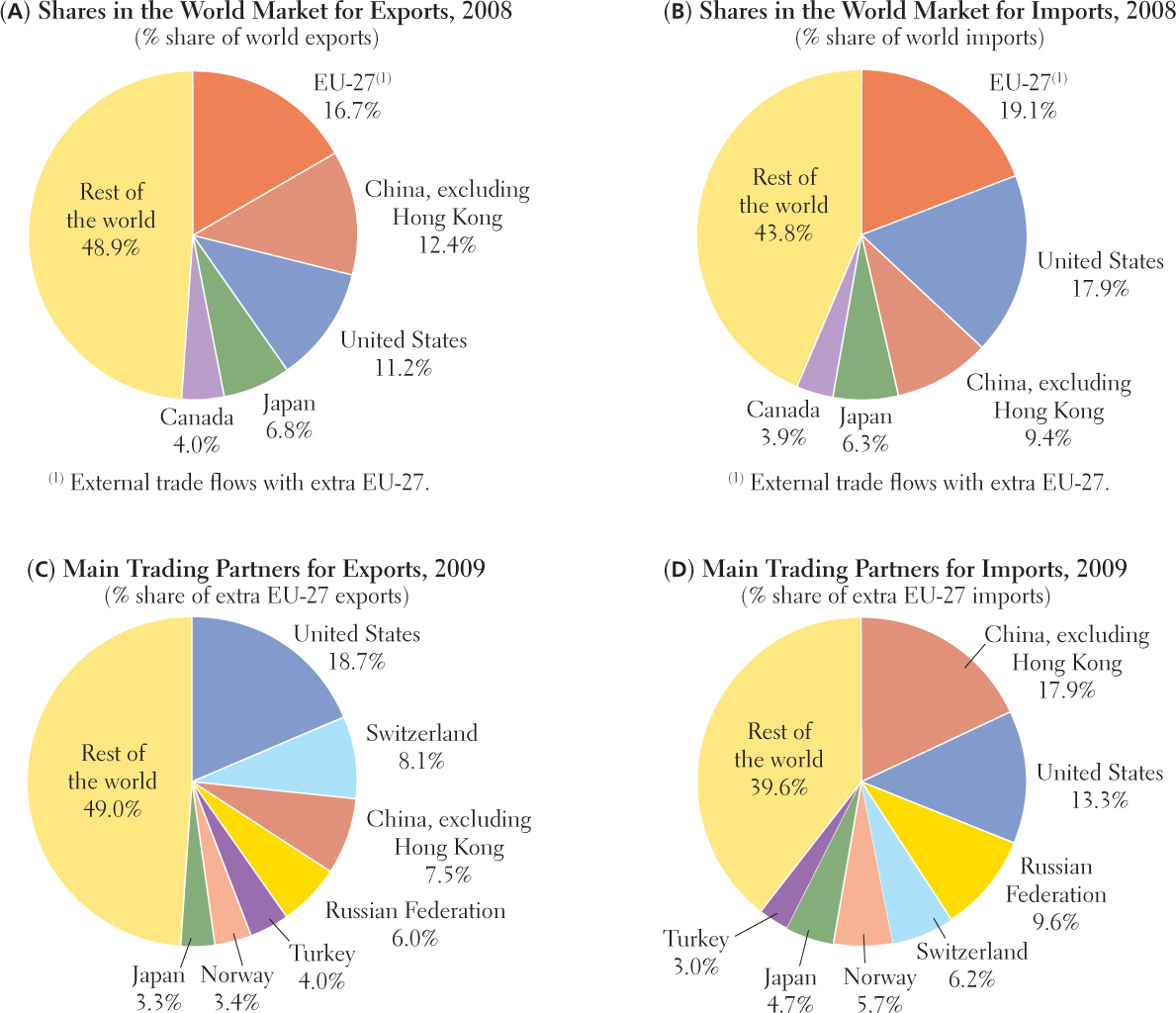

Like the United States, the European Union currently has a large share of world trade (Figure 4.15); it therefore exerts a powerful influence on the global trading system. The European Union often negotiates privileged access to world markets using preferential trade agreements, or PTAs, for European firms and farmers. The European Union also employs protectionist measures (tariffs) that favor European producers by making goods from outside the European Union more expensive. These higher-priced goods create added expense for European consumers but help ensure EU jobs and control over supplies. Of course, non-European producers shut out of EU markets are unhappy, and increasingly they have united to protest the EU’s failure to open its economies to foreign competition. So far, such protests have met with little success.

NATO and the Rise of the European Union as a Global Peacemaker

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) a military alliance between European and North American countries that was developed during the Cold War to counter the influence of the Soviet Union; since the breakup of the Soviet Union, NATO has expanded membership to include much of eastern Europe and Turkey, and is now focused mainly on providing the international security and cooperation needed to expand the European Union

A new role for the European Union as a global peacemaker and peacekeeper is developing through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which is based in Europe. During the Cold War, European and North American countries cooperated militarily through NATO to counter the influence of the Soviet Union. NATO originally included the United States, Canada, the countries of western Europe, and Turkey; it now includes almost all the EU countries as well.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, other nations came to assist the United States in the difficult task of addressing global security issues only after a major failure to avert a bloody ethnic conflict during the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991. NATO has since focused mainly on providing the international security and cooperation needed to expand the European Union. When the United States invaded Iraq in 1993, most EU members opposed the war. As worldwide opposition to the United States built, the global status of the European Union rose. With the United States preoccupied in Iraq, NATO assumed more of a role as a global peacekeeper. It now provides a majority of the troops in Afghanistan, but enthusiasm for this war has waned sharply in Europe.

214

In addition to the major role now played in Afghanistan, NATO and the European Union are also helping patrol the world ocean. In the spring of 2009 during the Somali pirate crisis off the northeast coast of Africa, NATO reported that both French and Portuguese naval vessels foiled attempts by pirates to seize merchant ships. Also in May of 2009, France announced that in accordance with its role in NATO, it had established a base in Abu Dhabi. During the Arab Spring that started in 2011, NATO undertook a number of noncombat operations in the Mediterranean, aimed at monitoring developing situations in Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mali.

94. NATO’S FUTURE ROLE DEBATED

94. NATO’S FUTURE ROLE DEBATED

95. NATO TO PROJECT DIFFERENT PHILOSOPHY

95. NATO TO PROJECT DIFFERENT PHILOSOPHY

96. CONCERN OVER COMMON VALUES AT THE U.S.–EU SUMMIT

96. CONCERN OVER COMMON VALUES AT THE U.S.–EU SUMMIT

97. NATO LEADERS, PUTIN MEET IN BUCHAREST

97. NATO LEADERS, PUTIN MEET IN BUCHAREST

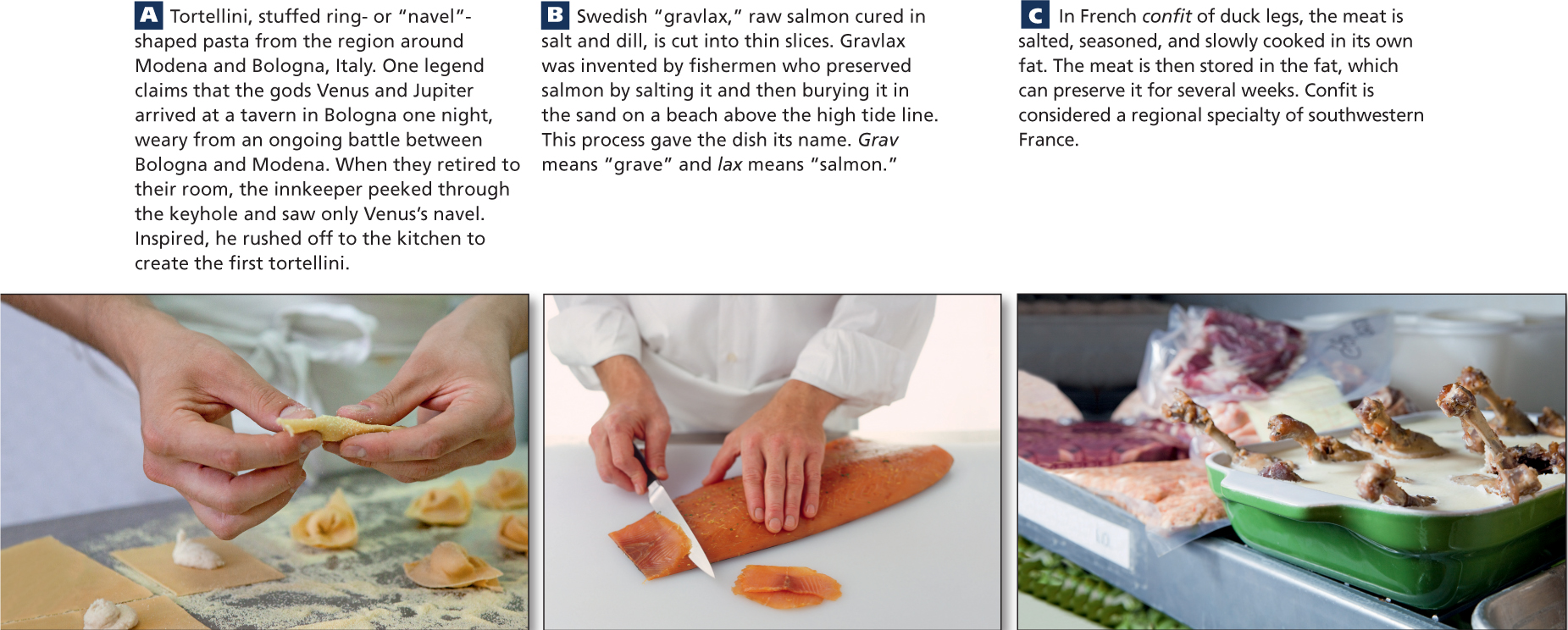

Food Production and the European Union

Geographic Insight 5

Food: Concerns about food security in Europe have led to heavily subsidized and regulated agricultural systems. Subsidies to agricultural enterprises account for nearly 40 percent of the budget of the European Union. Although large-scale food production by agribusiness is now dominant, there is a revival of organic and small-scale sustainable techniques.

Food security is especially important to Europeans, probably because stories of post-World War II food shortages are still so vivid. Most food is now produced on large, mechanized farms that are efficient, require less labor, and are more productive per acre than were farms before the 1970s. One result is that only about 2.3 percent of Europeans are now engaged in full-time farming. A second result of the efficiencies of agricultural mechanization is that the percentage of land in crops has declined since the mid-1990s, while forestlands have increased.

The Common Agricultural Program (CAP)

Common Agricultural Program (CAP) an EU program, meant to guarantee secure and safe food supplies at affordable prices, that places tariffs on imported agricultural goods and gives subsidies to EU farmers

The drastic decline of labor and land in farming affects Europeans emotionally, who see it as endangering their cultural heritage and the goal of food self-sufficiency (Figure 4.16). To address these worries, the European Union established its wide-ranging Common Agricultural Program (CAP), meant to guarantee secure and safe food supplies at affordable prices, provide a secure living for farmers, and preserve the quaint, rural landscapes nearly everyone associates with Europe.

subsidies monetary assistance granted by a government to an individual or group in support of an activity, such as farming, that is viewed as being in the public interest

The CAP helps farmers by placing tariffs on imported agricultural goods and by giving subsidies (in this case, payments to farmers) to underwrite the costs of production. Subsidies are expensive—payments to farmers are the largest category in the EU budget, still accounting for 38 percent of expenditures after negotiated reductions in 2013. While these policies do ensure a safe and sufficient food supply and provide a decent living standard for farmers, they also effectively raise food costs for millions of consumers. Moreover, because subsidies are based on the amount of land under cultivation, these payments favor large, often corporate-owned farms. It was this aspect of the CAP that the Smithfield company (with the help of its European partners) took advantage of in setting up its giant pig farms in Romania (recall the opening vignette).

Protective agricultural policies like tariffs and subsidies—also found in the United States, Canada, and Japan—are unpopular in the developing world. Tariffs lock farmers in poorer countries out of major markets. And subsidies encourage overproduction in rich countries (in order to collect more payments). The result is occasional gluts of farm products that are then sold cheaply on the world market, as is the case with Smithfield pork. This practice, called dumping, lowers global prices and thus hurts farmers in developing countries while it aids those in developed countries by reducing their supplies, which keeps their prices high.

215

Growth of Corporate Agriculture and Food MarketingAs small family farms disappear in the European Union—just as they did several decades ago in the United States—smaller farms are being consolidated into larger, more profitable operations run by European and foreign corporations (see Figure 4.5C). These farms tend to employ very few laborers and use more machinery and chemical inputs.

The move toward corporate agriculture is strongest in Central Europe. When communist governments gained power in the mid-twentieth century, they consolidated many small, privately owned farms into large collectives. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, these farms were rented to large corporations, which in turn further mechanized the farms and laid off all but a few laborers. Rural poverty rose. Small towns shrank as farmworkers and young people left for the cities. With EU expansion, the CAP has provided further incentives for large-scale mechanized agriculture, which is now found in Spain, Italy, and France.

A Case Study: Green Food Production in Slovenia

During the Communist era, Slovenia was unlike most of the rest of Central Europe in that the farms were not collectivized. As a result, the average farm size is just 8.75 acres (3.5 hectares). Although Slovenia has plenty of rich farmland, as standards of living have risen, it has become a net importer of food. Nonetheless, Slovenia’s new emphasis on private entrepreneurship, combined with a growing demand throughout Europe for organic foods, has encouraged some Slovene farmers to carve out an organic niche for themselves, first in local markets and eventually as exporters. The case of Vera Kuzmic is illustrative (Figure 4.17).aa

Thinking Geographically

Question

OCY1gQ9/6z5iJCSO/XzHWOGHlxIi+8ESPfey8HzP3zJT/Jj7zgjjJkMKUxIZG8cPQPz7Gle8JygdgZPc6XL2OBqWsATAIJ/nOjHrKNH2nqVwEYgyShBMupvYRPBdXQR04jPSf1WW1VYMONNAzz0MiB091KbzjJfybu/K09yejBhJ0SC25zwojRMs3jc6mYXUOWTgoKrMqRrJvsE4Hrn39F3DiGhxcW3yFq9BkDMhdzBZSCTw5xD5HjreKktk0wiGBCbAI1CNZV7TusIFFqCS7ZEagbOWeOeIql2RD0kLWZJR6aSsqSzllQQx5VBIcHBrwKnGVIpCtUhGUibUuiUJhBrRd4g34VaXEAwvW1/iH+mWabg/MfP6HtdqL86ytuZ9EP2rdphotBpoCRUx8a8x9vuxesaIN1oXMoBXYCsOvs2kmbO7PL+r+WvMKCmeKWiPom+l38ICajcrDwCS5GBWKUazgUJDr9Y8/VdhQhaO79m5P7jJeWxmIwYau9aEoUCqbA0wW5YryIsdmHF1gGFTNeJ+Bhxvgg3Ocl3Ig1+ORXp/8N60pkSG+6gG3p5cdcLNN+t98Aa9nZx3tVdCgA/cKLb9T8RAh7G1l4s8FlVX+eP+gR9uVIGNETTE

Vera Kuzmic (a pseudonym) lives 2 hours by car south of Ljubljana, Slovenia’s capital. For generations, her family has farmed 12.5 acres (5 hectares) of fruit trees near the Croatian border. In the economic restructuring that took place after Slovenia became independent in 1991, Vera and her husband lost their government jobs. The Kuzmic family decided to try earning its living in vegetable market gardening because vegetable farming could be more responsive to market changes than fruit tree cultivation. By 2000, the adult children and Mr. Kuzmic were working on the land, and Vera was in charge of marketing their produce and that of neighbors whom she had also convinced to grow vegetables.

Vera secured market space in a suburban shopping center in Ljubljana, where she and one employee maintained a small vegetable and fruit stall (Figure 4.17). Her produce had to compete with less expensive, Italian-grown produce sold in the same shopping center—all of it produced on large corporate farms in northeastern Italy and trucked in daily. But Vera gained market share by bringing her customers special orders and by guaranteeing that only animal manure, and no pesticides or herbicides, were used on the fields. However, when Slovenia joined the European Union in 2004, she had to do more to compete with produce growers and marketers from across Europe who now had access to Slovene customers.

Anticipating the challenges to come, the Kuzmics’ daughter Lili completed a marketing degree and the family incorporated their business. Lili is now its Ljubljana-based director, while Vera manages the farm. Lili’s market research showed the wisdom of diversification. The Kuzmics still focus on Ljubljana’s expanding professional population, who will pay extra for fine organic produce. But now, in a banquet facility on the farm built with CAP funds, Vera also prepares special dinners for bus-excursion groups from across Europe interested in witnessing traditional farm life and in tasting Slovene ethnic dishes made from homegrown organic crops. [Source: Lydia Pulsipher. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]aa

Europe’s Growing Service Economies

As industrial jobs have declined across the region, most Europeans (about 70 percent) have found jobs in the service economy. Services, such as the provision of health care, education, finance, tourism, and information technology, are now the engine of Europe’s integrated economy, drawing hundreds of thousands of new employees to the main European cities. For example, financial corporations that are located in London and serve the entire world play a huge role in the British economy, with many multinational companies headquartered in London.

216

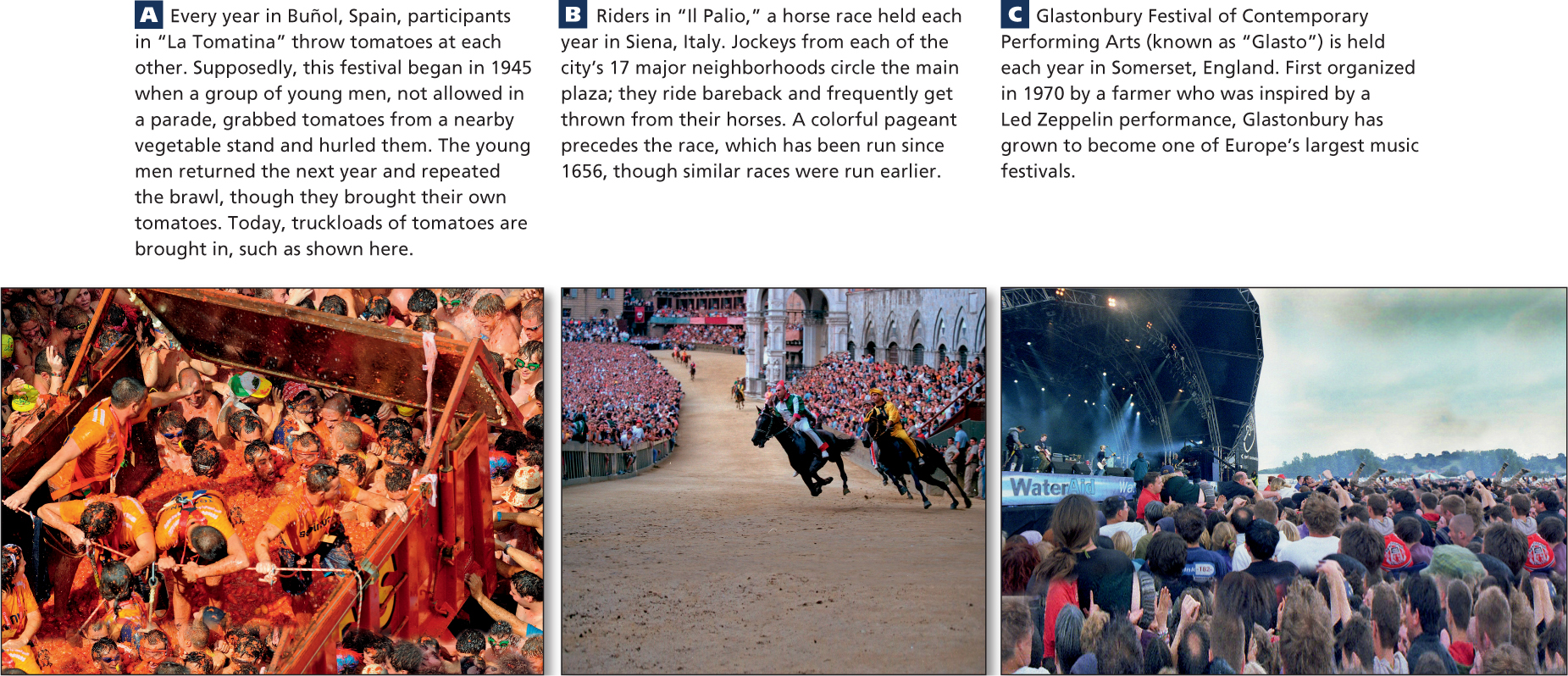

A major component of Europe’s service economy is tourism. Europe is the most popular tourist destination in the world, and one job in eight in the European Union is related to tourism. Tourism generates 13.5 percent of the EU’s gross domestic product and 15 percent of its taxes, although this varies with global economic conditions. Europeans are themselves enthusiastic travelers, frequently visiting one another’s countries to attend local festivals (Figure 4.18) as well as travelling to many distant locations throughout the world. This travel is made possible by the long paid vacations—usually 4 to 6 weeks—that Europeans are granted by employers. Vacation days can be taken a few at a time so that people can take numerous short trips. The most popular holiday destinations among EU members in 2011 were France, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Austria.

Service occupations increasingly involve the use of technology. While Europe has lagged behind North America in the development and use of personal computers and the Internet, it leads the world in cell phone use. The information economy is especially advanced in West Europe, though in South Europe and Central Europe, where personal computer ownership is lowest, public computer facilities in cafés and libraries are common.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The EU’s original plan was to reach a level of economic and social integration that would make possible the free flow of goods and people across national borders; for the most part, those goals have been reached among the current 28 members.

The EU’s original plan was to reach a level of economic and social integration that would make possible the free flow of goods and people across national borders; for the most part, those goals have been reached among the current 28 members. The European Union has one executive branch—the European Commission—and two legislative branches—the European Parliament, directly elected by EU citizens, and the Council of the European Union, whose members consist of one minister from each EU country.

The European Union has one executive branch—the European Commission—and two legislative branches—the European Parliament, directly elected by EU citizens, and the Council of the European Union, whose members consist of one minister from each EU country. The European Union joined the members’ national economies into a common market. By 2011, the EU’s economy was almost $15.65 trillion (PPP), about 2 percent larger than that of the United States, making the European Union the largest economy in the world.

The European Union joined the members’ national economies into a common market. By 2011, the EU’s economy was almost $15.65 trillion (PPP), about 2 percent larger than that of the United States, making the European Union the largest economy in the world. A new role for the European Union as a global peacemaker and peacekeeper is developing through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which is based in Europe.

A new role for the European Union as a global peacemaker and peacekeeper is developing through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which is based in Europe. _div_Geographic Insight 5_enddiv_Food Concerns about food security in Europe have caused EU members to invest tax money to ensure the survival of traditional farming and small-scale sustainable techniques, including the organic production of fruits, vegetables, and meats. The EU also subsidizes agricultural production on large corporate farms where agribusiness is now dominant.

_div_Geographic Insight 5_enddiv_Food Concerns about food security in Europe have caused EU members to invest tax money to ensure the survival of traditional farming and small-scale sustainable techniques, including the organic production of fruits, vegetables, and meats. The EU also subsidizes agricultural production on large corporate farms where agribusiness is now dominant. As industrial jobs have declined across the region, most Europeans (about 70 percent) have found jobs in the service economy.

As industrial jobs have declined across the region, most Europeans (about 70 percent) have found jobs in the service economy.