Physical Patterns

Landforms and climates are particularly closely related in this region. The climate is dry and hot in the vast stretches of the relatively low, flat land; it is somewhat more moist where mountains capture orographic rainfall. The lack of vegetation perpetuates aridity. Without plants to absorb and hold moisture, the rare but occasionally copious rainfall simply runs off, evaporates, or sinks rapidly into underground aquifers, of which there are many across the region.

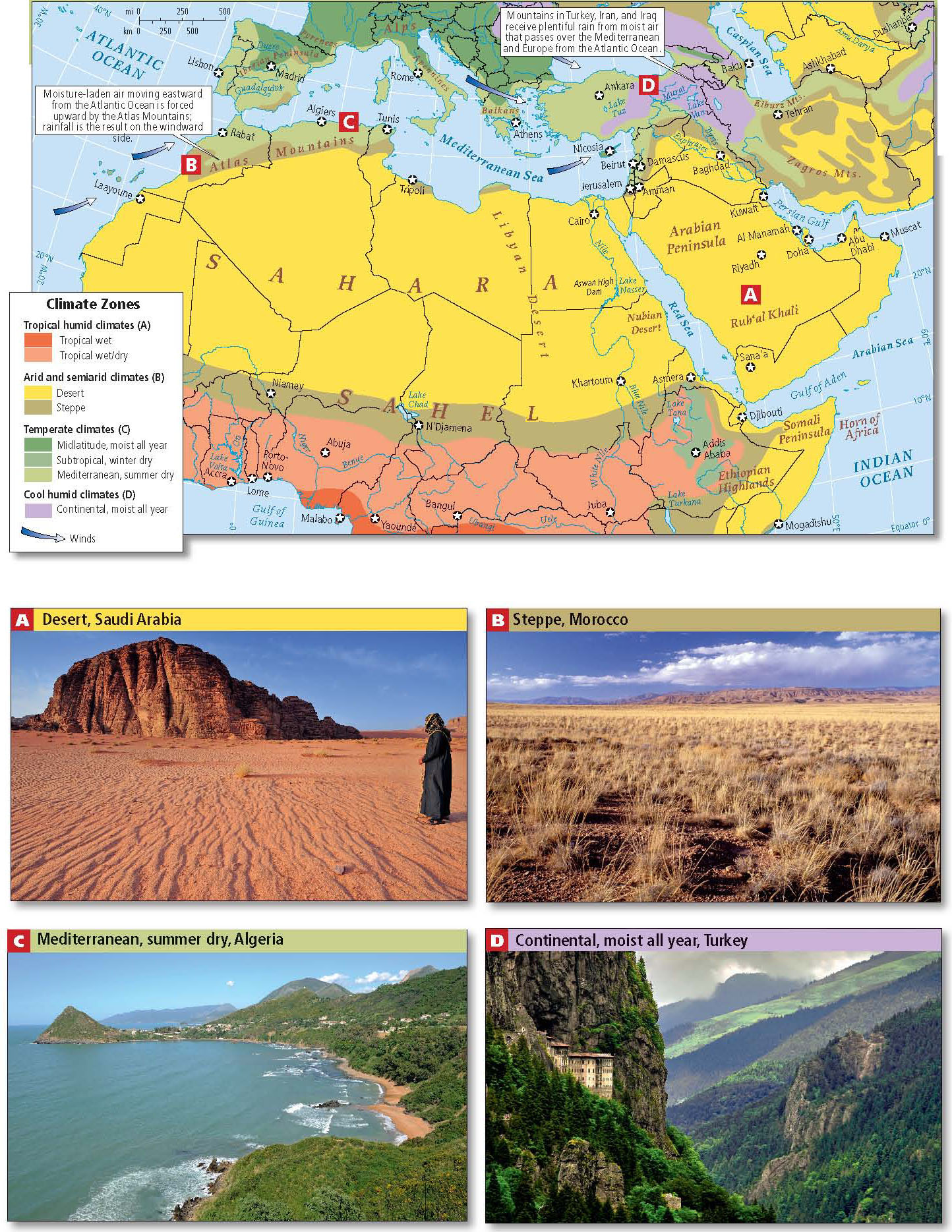

Climate

No other region in the world is as dry as North Africa and Southwest Asia (see Figure 6.5A). A belt of dry air that circles the planet between roughly 20° N and 30° N creates desert climates in the Sahara of North Africa, the eastern Mediterranean, the Arabian Peninsula, Kuwait, Iraq, and Iran.

The Sahara’s size and location under this high-pressure belt of dry air make it a particularly hot desert region. In some places, temperatures can reach 130°F (54°C) in the shade at midday (see Figure 6.1A). With little water or moisture-holding vegetation to retain heat, nighttime temperatures can drop quickly to below freezing. Nevertheless, in even the driest zones, humans survive as traders and nomadic herders at scattered oases, where they maintain groves of drought-resistant plants such as date palms. Desert inhabitants often wear light-colored, loose, flowing robes that reflect the sunlight, retain body moisture during the day, and provide warmth at night.

In the uplands and at the desert margins, enough rain falls to nurture grass, some trees, and limited agriculture. Such is the case in northwestern Morocco; along the Mediterranean coast in Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya; in the highlands of Sudan, Yemen, and Turkey; and in the northern parts of Iraq and Iran (see Figure 6.5B-D). The rest of the region, generally too dry for cultivation, has for generations been the prime herding lands for nomads, such as the Kurds of Southwest Asia, the Berbers and Tuareg (a branch of Berbers) in North Africa, and the Bedouin of the steppes and deserts on the Arabian Peninsula. Recently, most nomads have been required to settle down; some of their lands are now irrigated for commercial agriculture, but the general aridity of the region means that sources of irrigation water (rivers and aquifers) are scarce.

Landforms and Vegetation

The rolling landscapes of rocky and gravelly deserts and steppes cover most of North Africa and Southwest Asia (see the Figure 6.1 map and Figure 6.5). In a few places, mountains capture sufficient moisture to allow plants, animals, and humans to flourish. In northwestern Africa, the Atlas Mountains, which stretch from Morocco on the Atlantic coast to Tunisia on the Mediterranean coast, lift damp winds that originate in the Atlantic Ocean, creating orographic rainfall of more than 50 inches (127 centimeters) per year on windward slopes. In some Atlas Mountain locations, there is enough snowfall to support a ski industry (see Figure 6.1B).

302

303

A rift that formed between two tectonic plates—the African Plate and the Arabian Plate—separates Africa from Southwest Asia (see Figure 1.25). The rift, which began to form about 12 million years ago, is now filled by the Red Sea. The Arabian Peninsula lies to the east of this rift. There, mountains bordering the rift in the southwestern corner rise to 12,000 feet (3658 meters). They capture enough rainfall to sustain local agriculture, which has been practiced there for thousands of years. Irrigation has been used for millennia to increase yields.

Behind these mountains, to the northeast of the Arabian Peninsula, lies the great desert region of the Rub’al Khali. Like the Sahara, it has virtually no vegetation. The sand dunes of the Rub’al Khali, which are constantly moved by strong winds, are among the world’s largest, some as high as 2000 feet (610 meters; see Figure 6.1D).

The landforms of Southwest Asia are more complex than those of North Africa. The Arabian Plate is colliding with the Eurasian Plate and pushing up the mountains and plateaus of Turkey and Iran (see Figure 1.25). Turkey’s mountains lift damp air that passes over Europe and the Mediterranean from the Atlantic, resulting in considerable rainfall (see Figure 6.1E). Only a little rain makes it over the mountains to the interior of Iran, which is very dry. The tectonic movements that create mountains also create earthquakes, a common hazard in Southwest Asia.

There are only three major river systems in the entire region, and all have attracted human settlement for thousands of years. The Nile flows north from the moist central East African highlands (see Figure 6.1F). It crosses arid Sudan and desert Egypt and forms a large delta on the Mediterranean. The Euphrates and Tigris rivers both begin with the rain that falls in the mountains of Turkey; the rivers flow southeast to the Persian Gulf. Another much smaller river, the Jordan, starts as snowmelt in the uplands of southern Lebanon and flows through the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea. Most other streams are for most of the year dry riverbeds, or wadis, carrying water only after the generally light rains that fall between November and April (Figure 6.1G shows a wadi in Morocco).

North Africa and Southwest Asia were home to some of the very earliest agricultural societies. Today, rain-fed agriculture is practiced primarily in the highlands and along parts of the Mediterranean coast, where there is enough precipitation to grow citrus fruits, grapes, olives, and many vegetables, though supplemental irrigation is often needed. While irrigated agriculture is an age-old type of farming, it has become increasingly significant in modern times, both in the valleys of the major rivers, where seasonal flooding fills irrigation channels, and where aquifers are tapped by wells to provide water for cotton, wheat, barley, vegetables, and fruit trees.