2.8 URBANIZATION

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 4

Urbanization: A dramatic change in the spatial patterns of cities and suburbs has profoundly affected life in this very urbanized region. Since World War II, North America’s urban populations have increased by about 150 percent, but the amount of land they occupy has increased by almost 300 percent. This is primarily because of suburbanization and urban sprawl, which are companion processes to urbanization.

Today, close to 80 percent of North Americans live in metropolitan areas—cities of 50,000 or more, plus their surrounding suburbs and towns. Most of these people live in car-dependent suburbs built since World War II, where urban life bears little resemblance to that in the central cities of the past.

metropolitan areas cities of 50,000 or more and their surrounding suburbs and towns

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, cities in Canada and the United States consisted of dense inner cores and less-dense urban peripheries that graded quickly into farmland. Starting in the early 1900s, central cities began losing population and investment, while urban peripheries—the suburbs—began growing (Figure 2.21). Workers were drawn by the opportunity to raise their families in single-family homes in secure and pleasant surroundings on lots large enough for vegetable gardens and recreation. Most continued to work in the city, traveling to and from on streetcars.

suburbs populated areas along the peripheries of cities

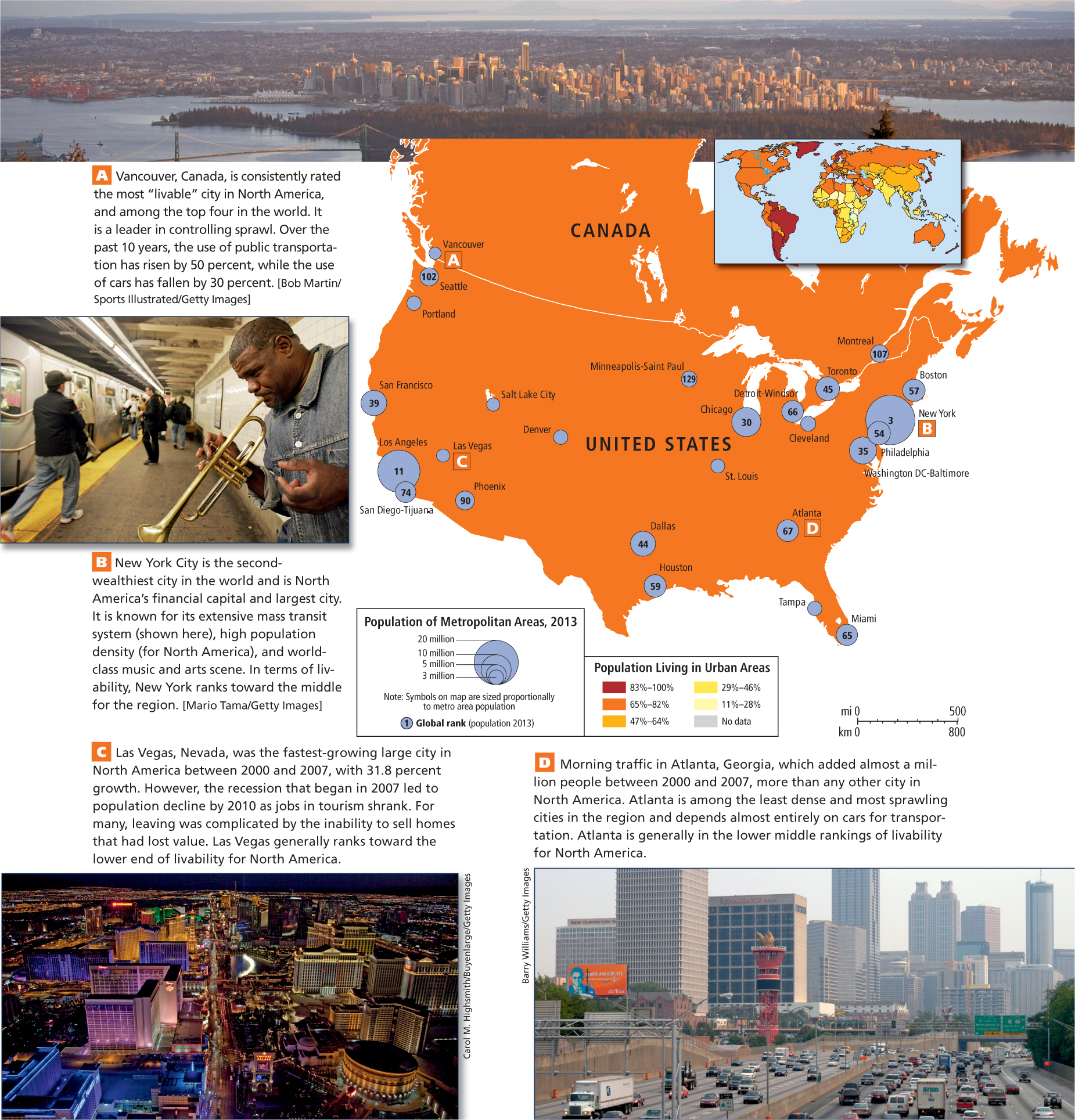

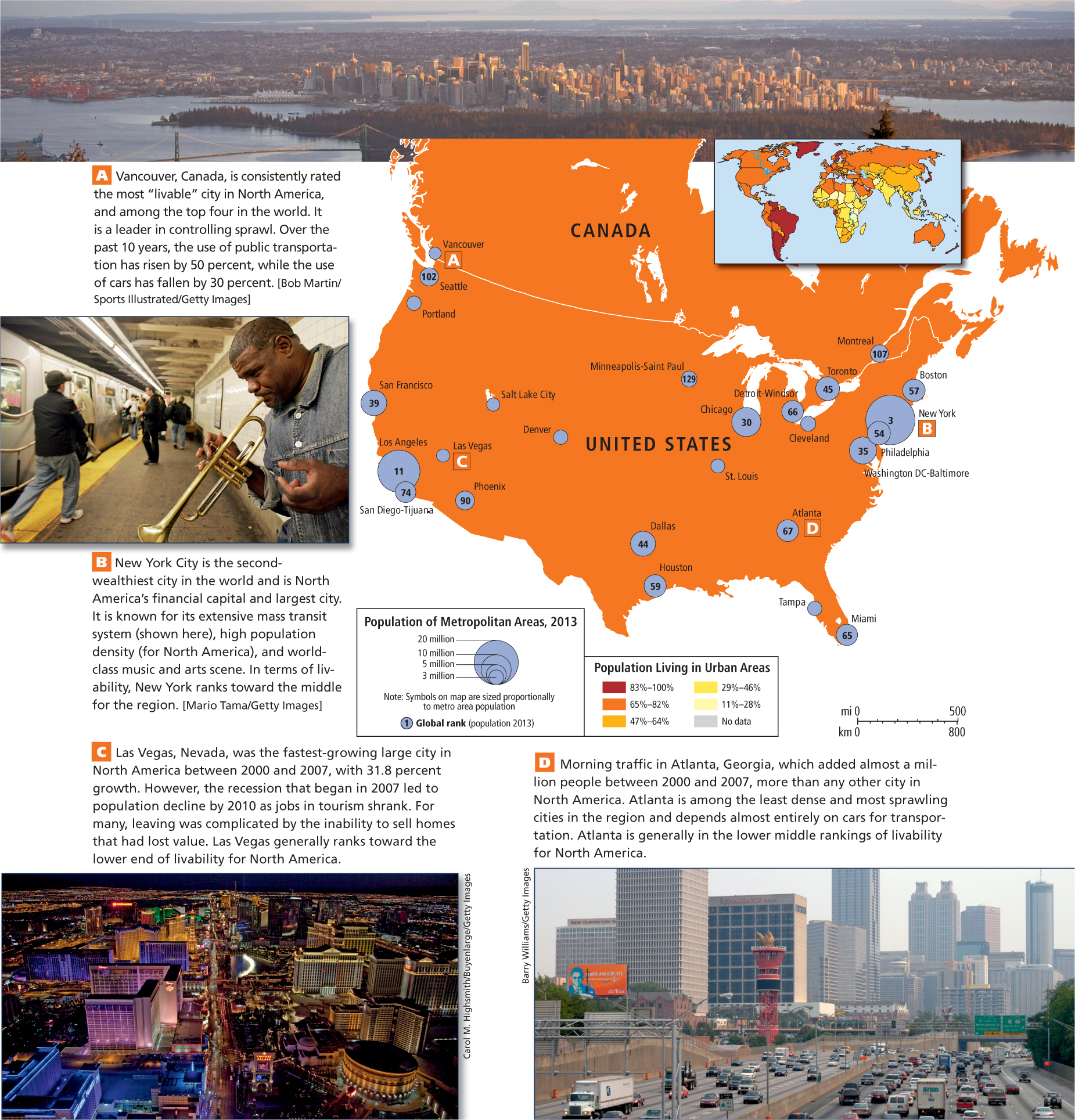

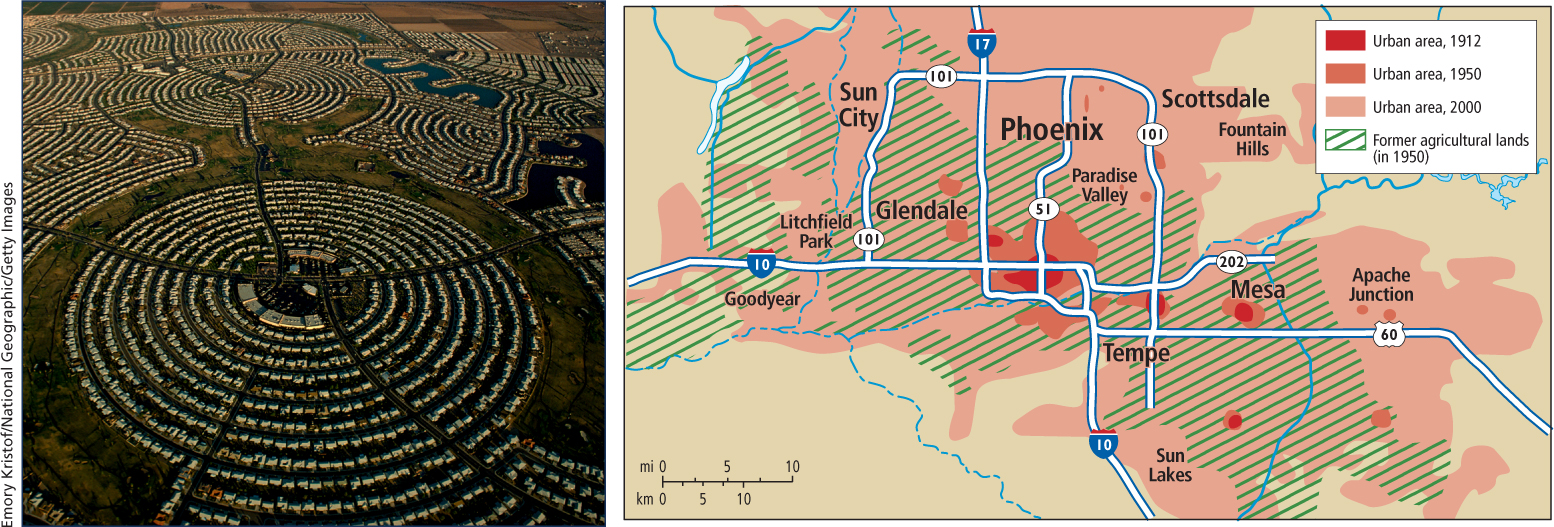

Figure 2.21: FIGURE 2.21 PHOTO ESSAY: Urbanization in North AmericaNorth America is very urbanized, with 79 percent of the population living in cities. Some of the wealthiest cities in the world are located here, though only a few have high levels of “livability.” Many cities, especially those in the United States, are characterized by sprawling development patterns that make people dependent on their automobiles.

[Sources consulted: 2011 World Population Data Sheet, Population Reference Bureau, at http://www.prb.org/pdf11/2011population-data-sheet_eng.pdf; World Gazetteer, at http://world-gazetteer.com/wg.php?x=&men=gcis&lng=en&des=wg&srt=npan&col=abcdefghinoq&msz=1500&pt=a&va=&srt=pnan]

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question

2.20

aHjF+16SijbIrwub195lpqyTcnAYcowpCQxmQeLfZfhLBEukA14/cj0ipjEyHadhbOzbLQOTwKBs/voEhcFBblZ+hAqwskfgg3lZ1PlmZMqOS21W

Question

2.21

WNE50Nw3dQVUvoxVLoMnpek02rvBo4c8uav5MDLDVFRu85LKvRFlQeMB+IN4yunstbRBrzU0+2sPvD3nffwfA96S/6c=

Question

2.22

bjevCxjfN4UCb5+jp5iQwPua9bOio6zwfevZLXDujmkBo8yTvbLryXAJkaA/yhhjQk6F0siFD28Z6usHBumBue8N5hk=

Question

2.23

TFD+PQaK4wDC/C1FuUm6/XbK2K2JxIKBu3rCqJbJJicHgkHY7gXCpi+uydk57REiv7CmOx8SIeRBlDN38YBBGuEcN6E=

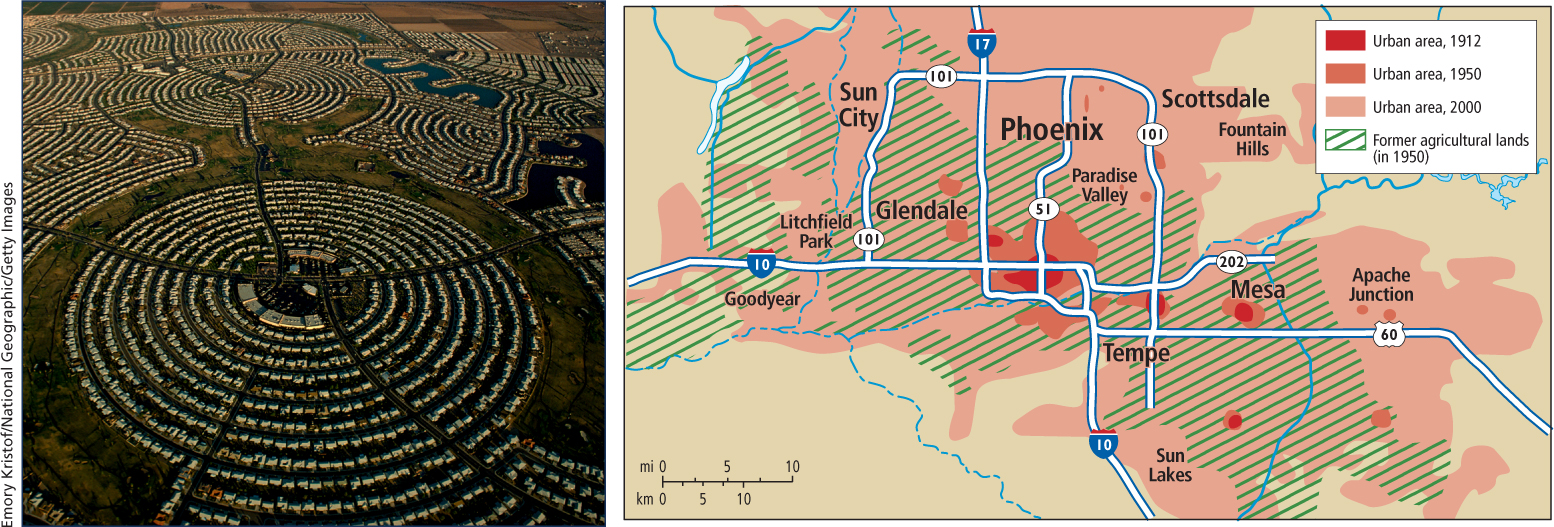

After World War II, suburban growth dramatically accelerated as cars became affordable to more people (Figure 2.22). In the United States, suburban growth was also encouraged by the federally funded Interstate Highway System, a network of free high-speed roads that passed through most cities, providing easy access to surrounding land along the interstate. Canada, with a less extensive interstate highway system and slightly fewer people who could afford cars, had less suburban growth.

Figure 2.22: Urban sprawl in Phoenix, Arizona. (A) Phoenix grew rapidly between 1950 and 2000, resulting in a demand for housing. The photo is of Sun City, a new, car-oriented suburb designed for senior citizens, located about 30 miles from Phoenix’s center. (B) This map shows the original urban settlement and how it has grown from 1912 to the present. A preference for single-family homes means that the city is sprawling into the surrounding desert rather than expanding vertically into high-rise apartments.

With the growing popularity of the family car, interest in publicly funded, non-car-based forms of transportation for these spreading urban areas dwindled. This process was hastened by a consortium of automobile manufacturers, tire companies, and oil companies that purchased, dismantled, and replaced many urban streetcars and light-rail trains with bus systems.

As North American suburbs grew and spread out, nearby cities often coalesced into a single urban mass. The term megalopolis was originally coined to describe the 500-mile (800-kilometer) band of urbanization stretching from Boston through New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, to south of Washington, DC. Other megalopolis formations in North America include the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles and its environs, the region around Chicago, and the stretch of urban development from Seattle–Tacoma to Vancouver, British Columbia.

megalopolis an area formed when several cities expand so that their edges meet and coalesce

VIGNETTE

For Canada’s First Nations people (the preferred term in Canada for Native Americans), the chance to indulge in the extravagance of urban sprawl is viewed positively. The Tsawwassen First Nation is one of 630 native groups that are negotiating with the Canadian government to gain full control over their ancestral territories. The land they recently received by a treaty lies 20 miles south of Vancouver, near the Strait of St. George. Eager to finally enjoy some of the fruits of development, they are planning a 2-million-square-foot “big box” and indoor shopping mall in the midst of what has been rural farmland. The surrounding communities, which had previously been able to shield their village-like settlements against urban sprawl, feel that there are enough shopping opportunities already. The Tsawwassen see the mall as an overdue chance for the prosperity that their neighbors already enjoy.

This pattern of urban sprawl requires residents to drive automobiles to complete most daily activities such as grocery shopping and commuting to work. Two major side effects of the dependence on vehicles that comes with urban sprawl are air pollution and emission of the greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change. Another important environmental consequence is the habitat loss that results when suburban development expands into farmland, forests, grasslands, and deserts.

Farmland and Urban Sprawl Urban sprawl drives farmers from land that is located close to urban areas, because farmland on the urban fringe is very attractive to real estate developers. The land is cheap compared to urban land, and it is easy to build roads and houses on since farms are generally flat and already cleared. As farmland is turned into suburban housing, property taxes go up and surrounding farmers who can no longer afford to keep their land sell it to housing developers. In North America each year, 2 million acres of agricultural and forest lands make way for urban sprawl.

Advocates of farmland preservation argue that beyond food and fiber, farms also provide economic diversity, soul-soothing scenery, and habitat for some wildlife. For example, the town of Pittsford, New York (a suburb of Rochester), decided that farms were a positive influence on the community. Mark Greene’s 400-acre, 200-year-old farm lay at the edge of town. As the population grew, the chances of the farm remaining in business for another generation looked dim. Land prices and property taxes rose, and the Greene family could not meet their tax payments. Residents in the new suburban homes sprouting up on what had been neighboring farms pushed local officials to halt normal farm practices, such as noisy nighttime harvesting or planting, spreading smelly manure, and importing bees to pollinate fruit trees. Pittsford, however, decided to stand by the farmers by issuing $410 million in bonds so that it could pay Greene and six other farmers for promises that they would not sell their 1200 acres to developers, but would instead continue to farm them.

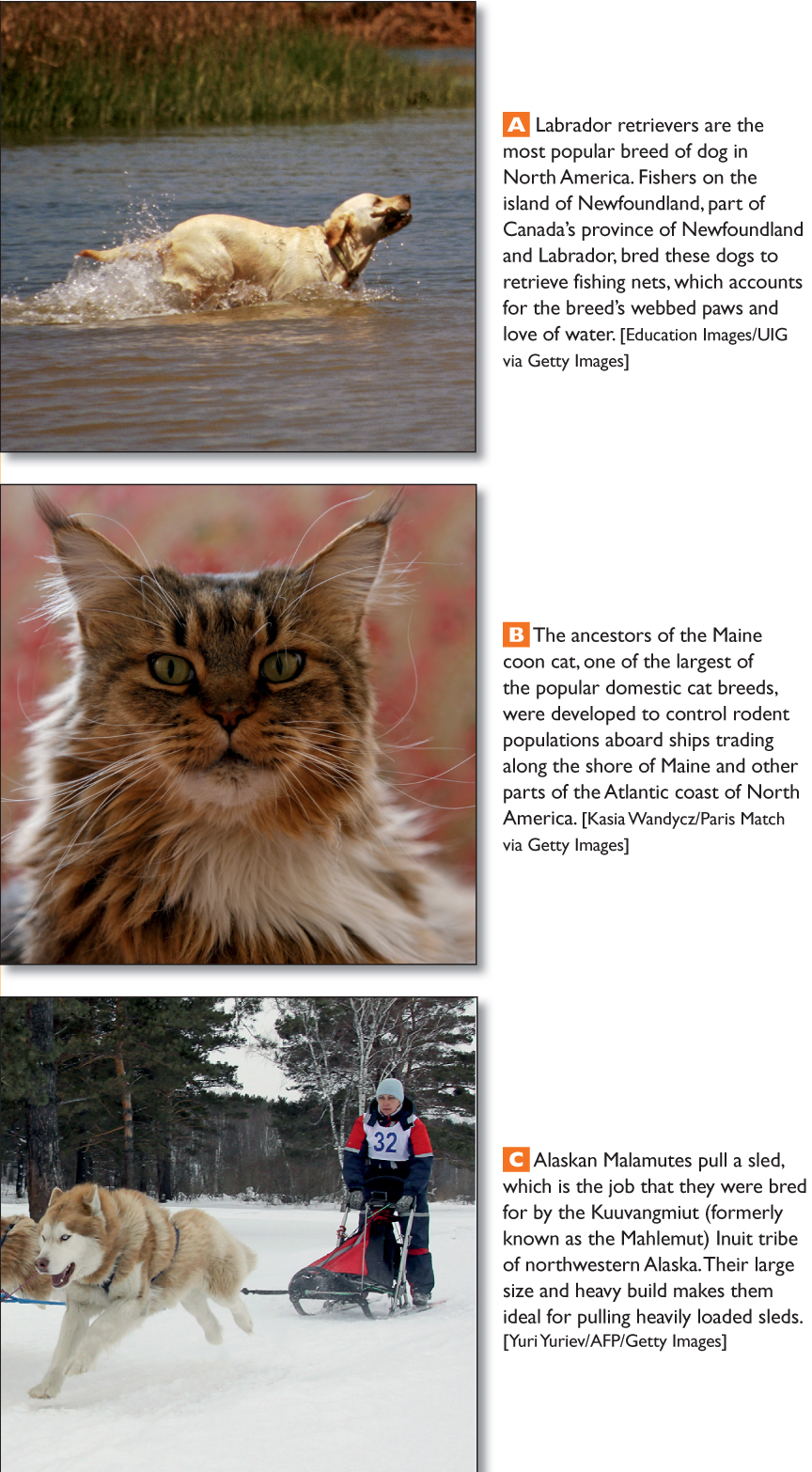

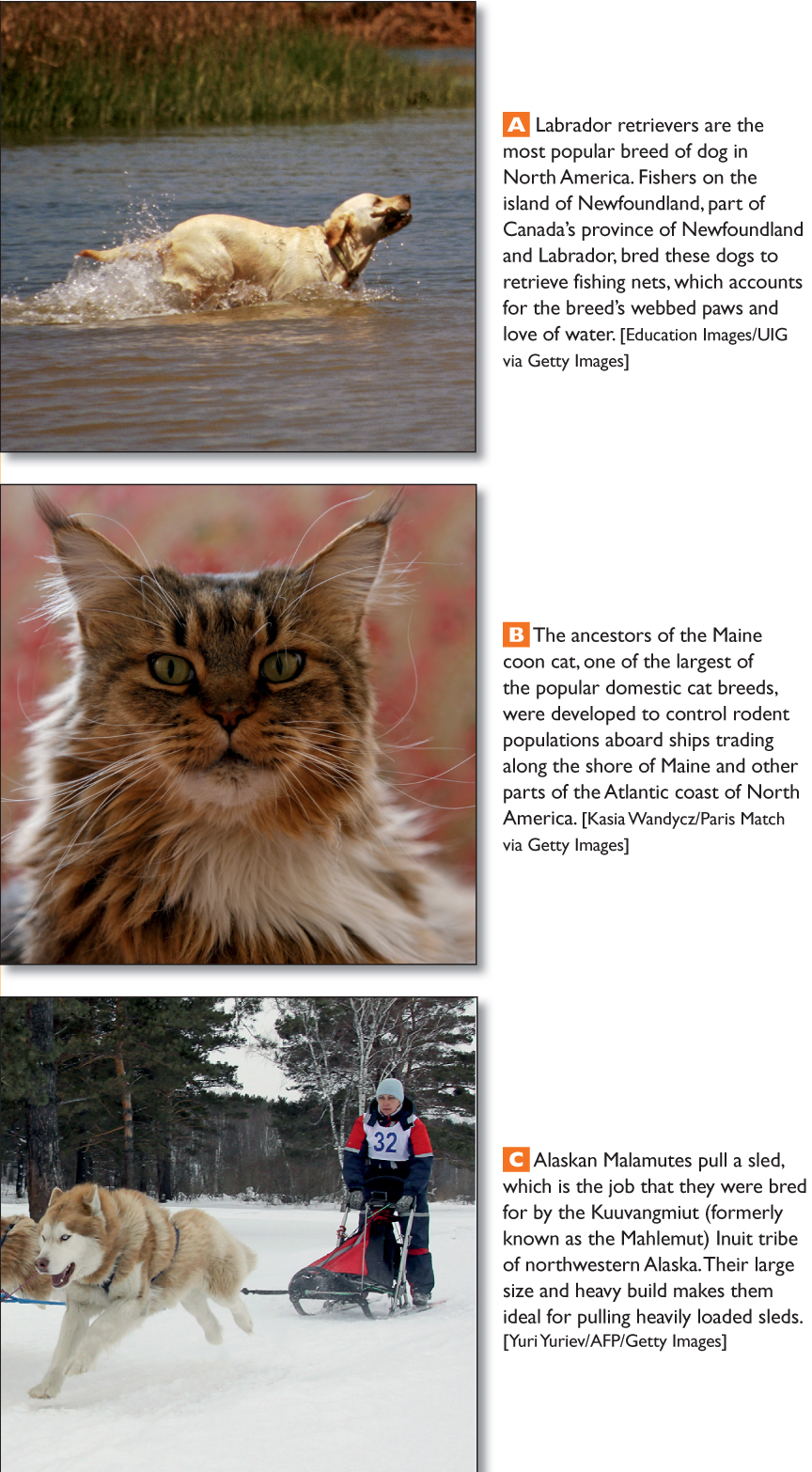

Smart Growth and Livability The term smart growth has been coined for a range of policies aimed at stopping sprawl by making existing urban areas more “livable.” Livability relates to factors that lead to a higher quality of life in urban settings, such as safety, good schools, affordable housing, quality health care, numerous and well-maintained parks that offer recreational opportunities for people and their pets (Figure 2.23), and well-developed public transportation systems. Some indexes of livability for major cities worldwide are put out every year by the Economist magazine and the Mercer Quality of Living Survey.

Figure 2.23: LOCAL LIVES People and Animals in North America

In smart growth planning, environmental benefits are envisioned as well. The focus on life lived locally, where mass transit and walking replace the family car and where gardening for food is a community entertainment, will result in lower energy use, air pollution, and CO2 emissions. While smart growth and the shift toward livability are just starting to take hold throughout North America, there are a few cities, such as Vancouver, British Columbia (see Figure 2.21A), and Portland, Oregon, where these principles are much further along in implementation.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Detroit, once the center of American auto industries, began to decline in the 1970s after a series of poorly made gas-guzzling automobiles tarnished the reputation of the car makers that had once provided the basis of the economy for the “Motor City.” Faced with stiff competition from car makers in Japan, companies like Ford and General Motors cut thousands of jobs and the city’s population shrank.

Forty years later, the depressing decay of a now much smaller Detroit is beginning to sprout with greenery and flowers as inner-city dwellers discover the joys of gardening on urban plots once occupied by houses that have since burned down. These green oases draw neighbors together and reconnect people with natural cycles. Children learn that food is something one can grow, not just buy.

Some older cities are enjoying a renaissance as people move back to them in search of greater livability. Places like New York City are arguably the furthest along in crucial aspects of smart growth, given their high density and widespread use of mass transit (see Figure 2.21B). However, the high cost of living in these places can reduce their livability.

It may be a while before smart growth and livability make much of an impact in some of North America’s fastest-growing large cities, such as Dallas, Atlanta, and Phoenix, where in recent years vast, car-dependent suburbs have spread out over enormous areas. Not surprisingly, none of these cities ranks high on livability indexes. Car dependence and rapid growth have brought Atlanta massive traffic jams and some of the worst air quality in the United States (see Figure 2.21D). Livability in the Las Vegas metro area is reduced by poor air and water quality as well as high crime rates (see Figure 2.21C).

Inner-city decay is another impact of sprawl on livability. This is especially true in the United States, where many inner cities are dotted with large tracts of abandoned former industrial land and neighborhoods debilitated by persistent poverty and loss of jobs. Old industrial sites that once held factories or rail yards are called brownfields. Because they are often contaminated with chemicals and covered with obsolete structures, blacktop, and concrete, they can be very expensive to redevelop for other uses. Also left behind in the inner cities are the least-skilled and least-educated citizens, many of whom were drawn in generations ago by the promise of jobs that have since moved out to the suburbs or overseas. Often the majority population in these inner cities is a mixture of African Americans, Asians, Latinos, and new immigrants. Some are relatively affluent and are leading efforts to renew old city centers. Others are in great need of the very services—health care, schools, and social support (including churches, synagogues, and mosques)—that have moved to the suburbs.

brownfields old industrial sites whose degraded conditions pose obstacles to redevelopment

The new emphasis on smart growth and livability has also reinforced the gentrification of old, urban residential districts. As affluent people invest substantial sums of money in renovating old houses and apartments, poor inner-city residents can be displaced in the process. The effect of gentrification on the displaced poor appears to be somewhat less harsh in Canada than in the United States, primarily because Canada’s stronger social safety net better ensures social services, housing, and help with housing maintenance. Some U.S. cities (such as Knoxville, Tennessee; Portland, Oregon; and Charlotte, North Carolina) have initiated New Urbanism projects to rehouse inner-city residents in pleasant, newly built, walkable urban neighborhoods with conveniently located services (Figure 2.24).

gentrification the renovation of old urban districts by affluent investment, a process that often displaces poorer residents

Figure 2.24: New Urbanism. Celebration, Florida, built in the 1990s, was designed to resemble older cities such as Charleston, South Carolina; New Orleans, Louisiana; Alexandria, Virginia; and Vicksburg, Mississippi.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Urbanization A dramatic change in the spatial patterns of cities and suburbs has profoundly affected life in this very urbanized region. Since World War II, North America’s urban populations have increased by about 150 percent, but the amount of land they occupy has increased by almost 300 percent. This is primarily because of suburbanization and urban sprawl, which are companion processes to urbanization.

After World War II, suburban growth dramatically accelerated as cars became affordable to more people.

Urban sprawl drives farmers from land that is located close to urban areas, because farmland on the urban fringe is very attractive to real estate developers.

The term smart growth has been coined for a range of policies aimed at stopping sprawl by making existing urban areas more “livable.”

One of the major impacts of urban sprawl, especially in the United States, is inner-city decay. Many inner cities are dotted with large tracts of abandoned former industrial land and have neighborhoods that are debilitated by persistent poverty and job loss.