3.1 Chapter 3 MIDDLE AND SOUTH AMERICA

108

109

chapter 3

MIDDLE AND SOUTH AMERICA▶

110

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHTS

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following issues as they relate to the five thematic concepts:

|

1. |

Environment: |

Deforestation in this region contributes significantly to global climate change through the removal of trees, which as living plants naturally absorb carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. Once the trees are cut or burned, they release large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Additionally, despite the region’s overall abundant water resources, some areas are experiencing a water crisis related to climate change, inadequate water infrastructure, and intensified use of water. |

|

2. |

Globalization and Development: |

The integration of this region with the global economy has left it with the widest gap between rich and poor in the world. Long- |

|

3. |

Power and Politics: |

After decades of rule by elites and the military, punctuated by disruptive foreign military interventions, political freedoms in Middle and South America are expanding. Almost all countries now have multiparty political systems and democratically elected governments. However, the international illegal drug trade continues to be a source of violence and corruption in the region. |

|

4. |

Urbanization: |

Since the early 1970s, Middle and South America has experienced rapid urban growth as rural people migrate to cities and towns. A lack of planning to accommodate the massive rush to the cities has created densely occupied urban landscapes that often lack adequate support services and infrastructure. |

|

5. |

Population and Gender: |

During the early twentieth century, the combination of cultural and economic factors and improvements in health care created a population explosion. By the late twentieth century, improved living conditions, expanded access to education and medical care, urbanization, and changing gender roles were all working together to reduce population growth. |

The Middle and South American Region

Middle and South America (Figure 3.1), like North America, is a region of great physical and cultural diversity; but here the cultural mix is richer and there are wider dispar i ties of wealth than in any other world region. In spite of the many similarities between the two regions, modern history in Middle and South America has been very different from that of North America.

The five thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues. Vignettes—

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

VIGNETTE

The boat trip down the Aguarico River in Ecuador took me into a world of magnificent trees, river canoes, and houses built high up on stilts to avoid floods. I was there to visit the Secoya, a group of 350 indigenous people locked in negotiations with the U.S. oil company Occidental Petroleum over Occidental’s plans to drill for oil on Secoya lands. Oil revenues supply 40 percent of the Ecuadorian government’s budget and are essential to paying off its national debt. The government had threatened to use military force to compel the Secoya to allow drilling.

The Secoya wanted to protect themselves from pollution and cultural disruption. As Colon Piaguaje, chief of the Secoya, put it to me, “A slow death will occur. Water will be poorer. Trees will be cut. We will lose our culture and our language, alcoholism will increase, as will marriages to outsiders, and eventually we will disperse to other areas.” Given all the impending changes, Chief Piaguaje asked Occidental to use the highest environmental standards in the industry. He also asked the company to establish a fund to pay for the educational and health needs of the Secoya people.

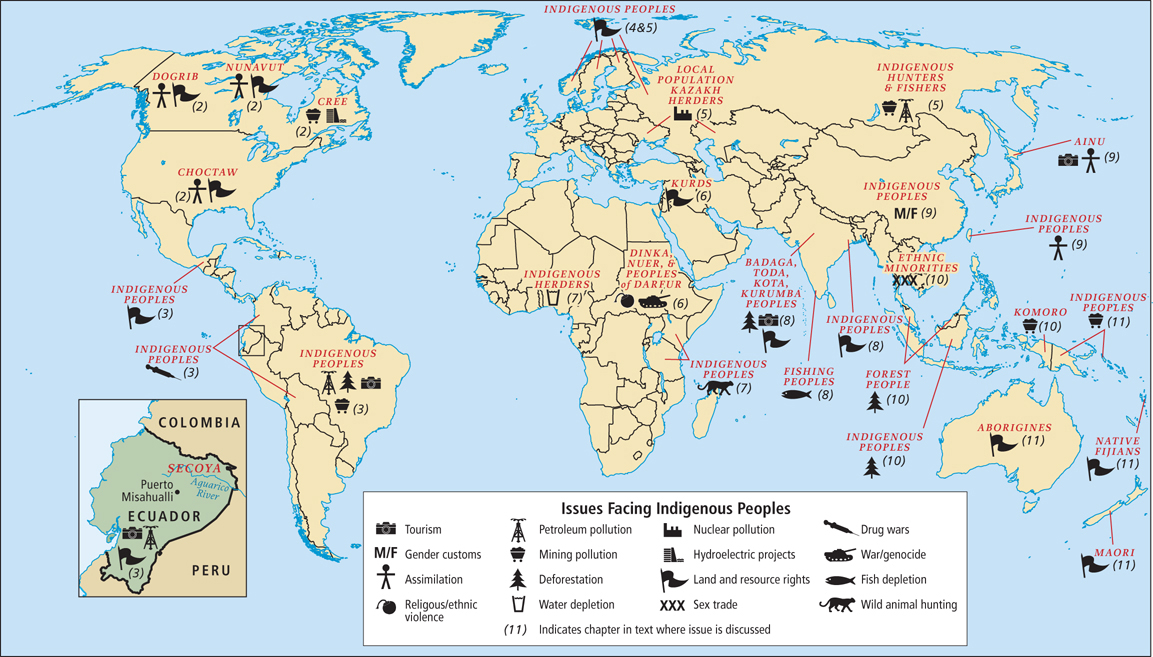

Like the Secoya, indigenous peoples around the world are facing environmental and cultural disruption arising from economic development efforts. Chief Piaguaje based his predictions for the future on what has happened in other parts of the Ecuadorian Amazon that have already had several decades of oil development.

The U.S. company Texaco was the first major oil developer to establish operations in Ecuador. From 1964 to 1992, its pipelines and waste ponds leaked almost 17 million gallons of oil into the Amazon Basin, enough to fill about 1900 fully loaded oil tanker trucks, or 35 Olympic-

In 1993, some 30,000 people sued Texaco in New York State, where the company (now owned by and called Chevron) is headquartered, for damages from the pollution. Those suing were both indigenous people and settlers who had established farms along Texaco/Chevron’s service roads. Several epidemiological studies concluded that contamination from oil has contributed to higher rates of childhood leukemia, cancer, and spontaneous abortions among people who live near the pollution created by Texaco/Chevron. Oil extraction has had many other negative effects on the environment. Air and water pollution have increased the rates of illness. The wildlife that the Secoya used to depend on, such as tapirs, has disappeared almost entirely because of overhunting by new settlers from the highlands who are working in the oil industry.

111

In 2002, the Ecuadorian suit against Chevron was dismissed by the U.S. Court of Appeals, which argued that it had no jurisdiction in Ecuador. The case was refiled in Ecuador in 2003, and 8 years later an Ecuadorian court ruled against Chevron, assessing damages of U.S.$18 billion. Chevron appealed to the Ecuadorian Supreme Court, which cut this amount in half. However, because Chevron no longer has any assets in Ecuador, the plaintiffs are preparing to file another lawsuit to collect the U.S.$9 billion in a country where Chevron does have assets, such as Canada. [Sources: Alex Pulsipher’s field notes; Amazon Watch, 2006; Oxfam America, 2005; National Public Radio. For detailed source information, see Text Sources and Credits.]

The rich resources of Middle and South America have attracted outsiders since the first voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Europe’s encounter with this region marked a major expansion of the global economy. However, during most of the period of expansion, Middle and South America occupied a disadvantaged position in global trade, supplying cheap raw materials that aided the Industrial Revolution in Europe and then North America but reaping few of the profits. These extractive industries did little to advance economic development within the region, as most profits went to foreign investors, and the negative environmental effects were largely ignored. In recent years, countries such as Ecuador, Mexico, Bolivia, Brazil, and Venezuela have worked to control their own resources, develop local manufacturing and service-

The Ecuadorians’ efforts to secure a damage settlement against a powerful multinational corporation is indicative of changing attitudes in this region and others (Figure 3.3) toward outside developers. Governments are now somewhat more wary when they lure investors to develop new extractive, manufacturing, and service industries. Local people are more aware that they must be vigilant to ensure that development serves their interests.

What Makes Middle and South America a Region?

Physically, the Middle and South America region consists of Mexico, which geologically is part of the North American continent; the isthmus (land bridge) of Central America; and the continent of South America. For the last 500 years, the region of Middle and South America has been defined by a colonial past very different from that of Canada and the United States. Most of the countries in Middle and South America were at one time colonies of Spain. The exceptions are Brazil, which was a colony of Portugal, and a few small countries that were possessions of Britain, France, the Netherlands, Germany, or Denmark (see Figure 3.12).

isthmus a narrow strip of land that joins two larger land areas

Today, Middle and South America is a region of contrasts and disparities. Culturally, this region has large indigenous populations that have contributed to every aspect of life, blending with and changing the European, African, and Asian cultures introduced by the colonists. Social stratification based on class, race, and gender is notable; economically, the gap between rich and poor is the widest of any world region. Politically, the region’s more than three dozen countries exhibit a range of governing ideologies, from the socialism of Cuba to the capitalism of Chile. Yet despite these contrasts and disparities, there are significant commonalities across the region, such as the Spanish language, Catholicism, and increasing development trajectories connected to the global economy.

indigenous native to a particular place or region

Terms in This Chapter

In this book, Middle America refers to Mexico, Central America (the narrow ribbon of land, or isthmus, that extends south of Mexico to South America), and the islands of the Caribbean (Figure 3.4). South America refers to the continent south of Central America. The term Latin America is not used in this book because it describes the region only in terms of the Roman (Latin-

Middle America in this book, a region that includes Mexico, Central America, and the islands of the Caribbean

South America the continent south of Central America

112

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The region of Middle and South America, heavily impacted by European colonialism, is making a shift away from raw materials–

based industries to more profitable manufacturing and service- based industries. As people in this region gain more control over their own resources, some are searching for more sustainable ways to develop economically.