4.1 Chapter 4 EUROPE

150

151

chapter 4

EUROPE▶

152

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHTS

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following issues as they relate to the five thematic concepts:

|

1. |

Environment: |

The European Union (EU) is a world leader in responding to climate change. Its goals for cutting greenhouse gas emissions are complemented by its many other strategies for saving energy and resources. However, much of Europe’s air and many of its seas and rivers are very polluted, and consumption patterns in the region impact environments across the globe. |

|

2. |

Globalization and Development: |

In order to better compete in the global economy, the EU has shifted labor- |

|

3. |

Power and Politics: |

Following World War II, political freedoms have grown and strong welfare states have been established in this region. Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, international politics within Europe have centered on the expansion of the EU into Central Europe and the development of EU political institutions. Having grown so much in the past several decades, the European Union, which is already a global economic power, could become a global counterforce to the United States in political and military affairs. |

|

4. |

Urbanization: |

Europe’s cities are both ancient and modern, with old town centers now surrounded by modern high- |

|

5. |

Population and Gender: |

Europe’s population is aging as its fertility rates decline, which they are doing for a number of reasons, including the fact that career- |

The European Region

Over the last 500 years, the region of Europe (shown in Figure 4.1) has had a central role in world history and geography as a colonizer of distant territories and as a major player in the development of capitalism. In the twentieth century, Europe brought the world to the edge of disaster with two massive wars. Since then it has revived, prospered, and designed a model for regional economic and political integration that has been copied in other regions. Europe is now at another important juncture: Can it perfect its union and extend it, or will the union dissolve in the face of growing subregional financial and social disparities? The five thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of these regional issues. Scattered throughout the chapter, vignettes illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

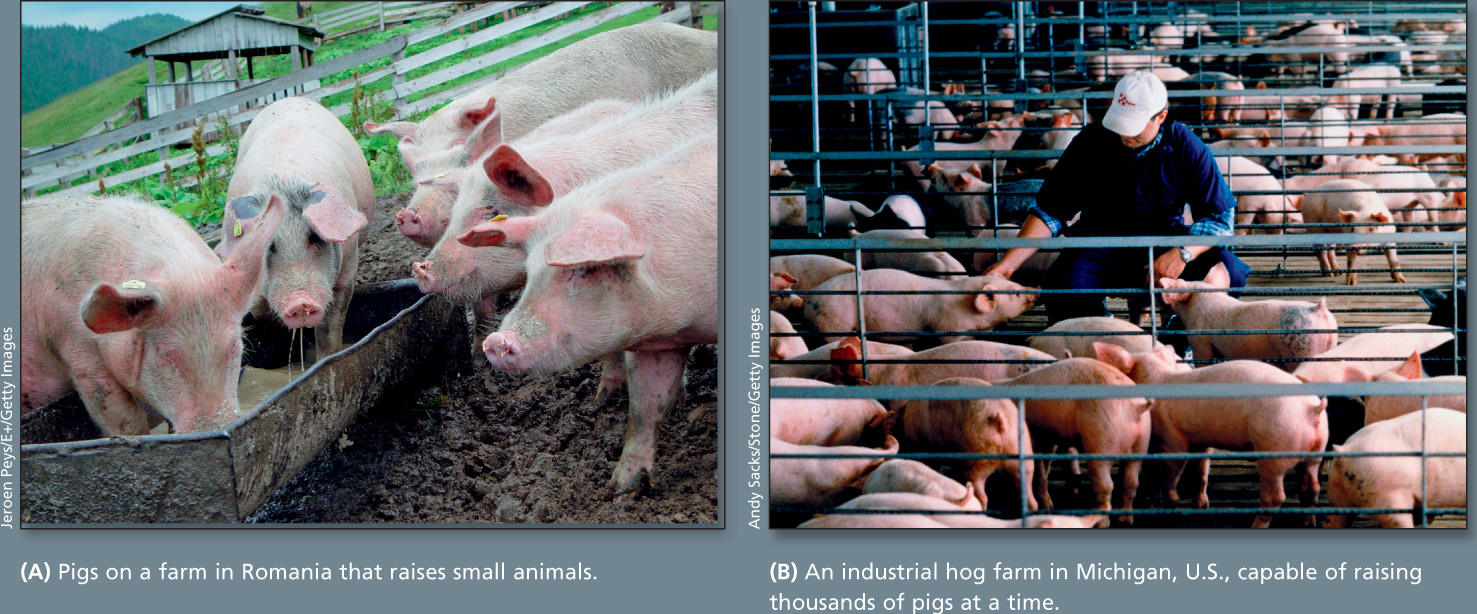

Grigore Chivu (a pseudonym) wanders through the empty pig pens on his farm near Lugoj in western Romania. For generations, his family has made a meager but rewarding living by raising hogs and then processing and selling the meat. A few years ago, just before Romania joined the European Union (EU), he had more than 250 pigs. At Christmas, he and thousands of pig farmers across the country would slaughter a certain number of their pigs and preserve the meat using time-

When Romania entered the European Union in 2007, all farmers were required to conform to EU standards for processing meat. The old methods were no longer allowed and for some the new standards were prohibitively expensive.

At first the farmers were uncertain just how to respond. Before they could organize a butchering cooperative that conformed to EU standards and for which development funds were available, an American company (based in Virginia) stepped into the breach. Smithfield, the world’s largest pork producer, was expanding operations into Central Europe, where it planned to produce pork and pork products on an industrial scale and market them globally. Eager to enter the EU market, Smithfield enlisted the help of Romanian politicians and got permission (and even EU subsidies) to establish a conglomerate that included feed production, pig breeding, modernized sanitary barns for fattening thousands of hogs in small cages, and slaughterhouses.

153

In September of 2013, Smithfield was bought by a Chinese company, Shuanghui, which planned to redirect much of the company’s global production toward supplying China’s growing demand for pork. Shortly after Shuanghui purchased Smithfield, Romanian officials signed agreements with their Chinese counterparts to export more than 3 million pigs to China each year. With Romania already importing half of its own pork, the recently established Smithfield facilities are now seen as key to boosting production to keep up with the Chinese demand.

As the old, picturesque Romanian agricultural landscape is transformed into huge factory farms, the number of independent pig farmers is dropping; it has been reduced by more than 90 percent (Figure 4.2). Unable to compete with the lower prices Smithfield can charge, Grigore Chivu, like thousands of his fellow pig farmers, was considering migrating to western Europe, where stronger economies meant better-

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Question 4.1

BmL4YzwaUzvd7qkHlxGjMrWcHMwMXF7J7/TKkzvLmTelizN9WwPq79/cV99wp8Kg+xQoF9wggZWyMeiItC+2QKt7nmBHZQZgiiMRkzT9e0syLuP9XZpU6ihWyAfCw+53ZIgP+jAdHQUMUihDazxH4G+NsV4zzeFAGrigore Chivu is faced with disruptive change as his country adjusts to new circumstances in the European Union and the global economy, but he is also part of a global revolution in food production and marketing that is changing food patterns across the world. For example, Smithfield pork, produced and processed at low cost in Romania, is now marketed in China, a country whose reliance on imported food and factory farming is growing. Most small-

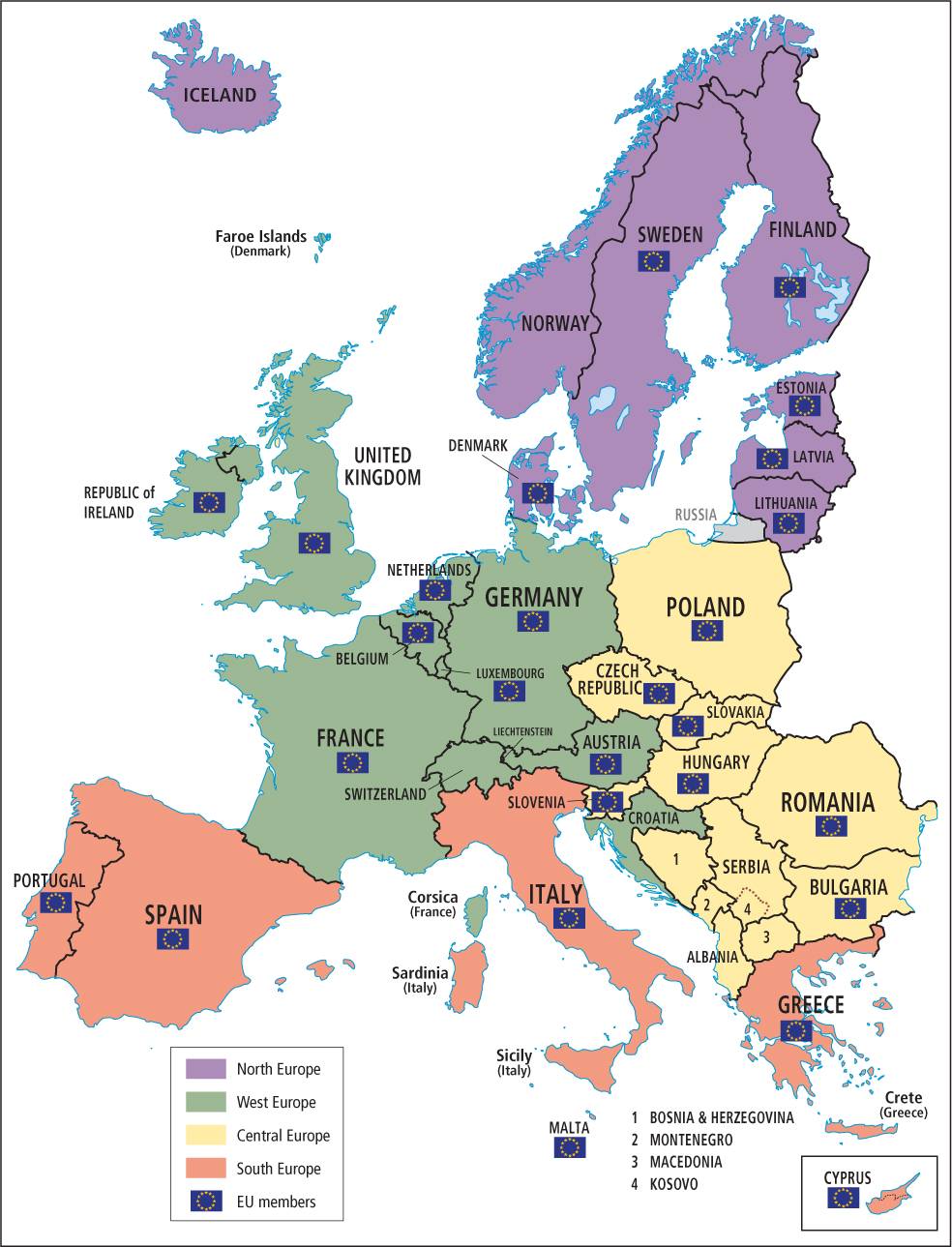

The European Union (EU) is a supranational organization that unites most of the countries of West, South, North, and Central Europe (Figure 4.3). In principle, people, goods, and money can move freely throughout the European Union. Many people, like Grigore Chivu, decide to migrate only reluctantly, and do so only because poorer regions do not have the political power to push for useful reforms.

European Union (EU) a supranational organization that unites most of the countries of West, South, North, and Central Europe

There are now 28 countries in the European Union; Croatia joined in 2013 and a few more hope to join in the next several years. The newest members (with the exceptions of Malta and Cyprus) are formerly Communist countries in Central Europe and generally have lower standards of living. Hundreds of thousands of workers from Central Europe have moved to other EU states to find better jobs. More recently, with rising job losses throughout the EU, many have returned home.

Since 2008, the European Union has been under growing financial stress as a number of the less industrialized and less prosperous countries (Greece, for example) have found it so hard to make loan payments that they face the possibility of national bankruptcy. Residents of the original and more prosperous EU members—

cultural homogenization the tendency toward uniformity of ideas, values, technologies, and institutions among associated culture groups

154

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Throughout the European Union, smaller family-

run farms are giving way to larger farms run by corporations. This change is strongest in those Central Europe countries that have been recently admitted to the European Union and has resulted in many farm family members migrating to other EU countries in search of work.

What Makes Europe a Region?

Physically, Europe is a peninsula extending off the western end of the huge Eurasian continent. There are many peninsular appendages, large and small, on this giant peninsula of Europe. Norway and Sweden share one of the larger appendages. Other large peninsulas are the Iberian Peninsula (occupied by Portugal and Spain), as well as those of Italy and Greece. All extend into either the Atlantic Ocean or into the various seas that are adjacent to the Atlantic (see the Figure 4.1 map).

155

The perimeter of the region of Europe to the north, west, and south is primarily oceanic coastline. This unique access to the world ocean facilitated European exploration and colonization of distant territories. The eastern physical and cultural border of Europe has been difficult to define. Just where Europe ends and Asia begins has been a source of contention for millennia. In this book, at this time, the eastern limit of the European region is taken to be the border of the European Union. Other potential parts of Europe—

Terms in This Chapter

This book divides Europe into four subregions (see Figure 4.3)—North, West, South, and Central Europe. Central Europe refers to all those countries formerly in the Soviet sphere that are now in the European Union, as well as the countries that were formerly in Yugoslavia, plus Albania.

For convenience, we occasionally use the term western Europe to refer to all the countries that were not part of the experiment with communism in the Soviet sphere and in Yugoslavia. That is, western Europe comprises the combined subregions of North Europe (except Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), West Europe (except the former East Germany), and South Europe. When we refer to the countries that were part of the Soviet sphere up to 1989, we use the pre-