5.9 SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES

When the winds of change began to blow through the Soviet Union in the 1980s, few people anticipated the rapidity and depth of the transformations or the social instability that resulted. On the one hand, new freedoms have encouraged self-

Gender: Challenges and Opportunities in the Post-Soviet Era

Soviet policies that encouraged all women to work for wages outside the home have transformed this region. By the 1970s, ninety percent of able-

These special pressures on working women affected diets because there was so little time or space for cooking and there were so few helpful appliances. The everyday cuisine in most of the region was limited during the Communist era; only recently have market forces made a wider range of food available. Traditional recipes are now being revived. Figure 5.24 shows several distinct dishes of the region that are prepared at home or in restaurants. The popularity of hearty soups and stews and the common use of root vegetables and grains (bread is an essential part of every meal) reflect the region’s climate, soil, and agricultural systems.

225

When the first market reforms in the 1980s reduced the number of jobs available to all citizens, President Gorbachev encouraged women to go home and leave the increasingly scarce jobs to men. Many women lost their jobs involuntarily. By the late 1990s, women made up 70 percent of the registered unemployed, despite the fact that because of illness, death, or divorce, many if not most were the sole support of their families. Consequently, many had to find new jobs.

On average, the female labor force in Russia is now more educated than the male labor force. The same pattern is emerging in Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, and parts of Muslim Central Asia. In Russia, the best-

The Trade in Women During the economic boom stimulated by marketization and oil and gas wealth, the “marketing” of women became one of the less savory entrepreneurial activities. One part of this market is the Internet-

Sex work has also increased in recent years. Precise numbers are hard to come by, but a 2010 UN report estimates that 140,000 women have been smuggled into Europe, where they become part of a sex trade that generates $3 billion annually. The post-

trafficking the recruiting, transporting, and harboring of people through coercion for the purpose of exploiting them

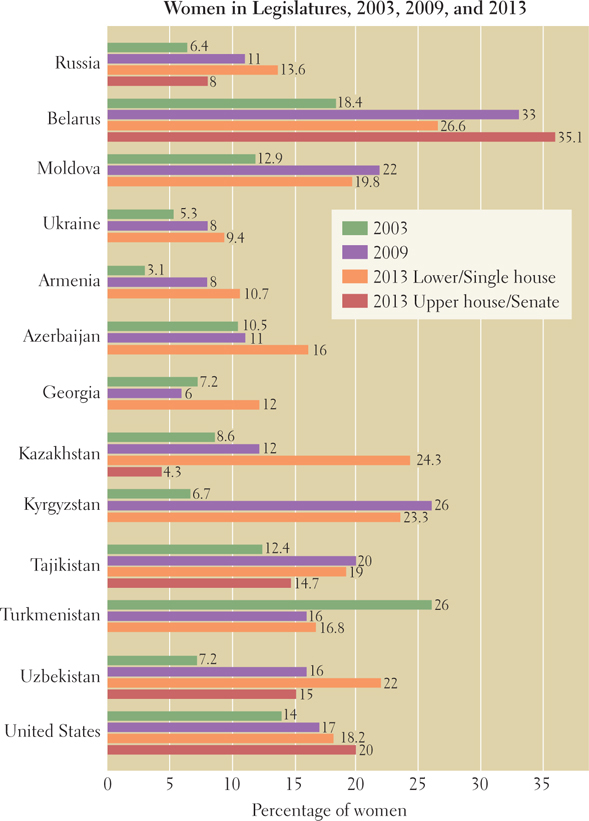

The Political Status of Women One way for women to address institutionalized discrimination is to increase their political power. Although women were granted equal rights in the Soviet constitution, they never held much power. In 1990, women accounted for 30 percent of Communist Party membership but just 6 percent of the governing Central Committee. The very few in party leadership often held these positions at the behest of male relatives.

226

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the political empowerment of women has grown somewhat, but long-

Religious Revival in the Post-Soviet Era

The official Soviet ideology was atheism, and religious practice and beliefs were seen as obstacles to revolutionary change. Orthodox Christianity, which was the official religion of the Russian Empire, was tolerated, but few people went to church, in part because the open practice of religion could be harmful to one’s career. Now, religion is a major component of the general cultural revival across the former Soviet Union.

The overall level of religiosity is moderate in Russia by global standards but a number of people, especially those from indigenous ethnic minority groups, are turning back to ancient religious traditions. For example, the Buryats from east of Lake Baikal in Siberia, who are related to the Mongols, are relearning the prayers and healing ceremonies of the Buryat version of Tibetan Buddhism, which they adopted in the eighteenth century. The shamans who lead them have organized into a guild to give official legitimacy to their spiritual work. They now pay taxes on their clergy income.

In Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Georgia, and Armenia, most people have some ancestral connection to Orthodox Christianity. Those with Jewish heritage form an ancient minority, mostly in the western parts of Russia and Caucasia, where they trace their heritage back to 600 b.c.e. Religious observance by both groups increased markedly in the 1990s, and many sanctuaries that had been destroyed or used for nonreligious purposes by the Soviets were rebuilt and restored.

A countertrend to the robust revival of Orthodox Christianity is the spread of evangelical Christian sects from the United States (Southern Baptists, Adventists, and Pentecostals). Evangelical Christianity first came to Russia in the eighteenth century, but after 1991, American missionary activity increased markedly. The notion often promoted by this movement—

In Central Asia, Islam was repressed by the Soviets, who feared Islamic fundamentalist movements would cause rebellion against the dominance of Russia. Today, Islam is openly practiced and is increasingly important politically across Central Asia, Azerbaijan, and some of the Russian Federation’s internal ethnic republics, such as Chechnya and Tatarstan. Especially in the Central Asian states, however, the return to religious practices is often a subject of contention. Some local leaders still view traditional Muslim religious practices as obstacles to social and economic reform.

227

Militant Islamic movements have often been violently repressed by Central Asian governments, in part out of fear of influences from nearby countries where Islam plays a greater role in politics. In some cases, these influences are clear—

THINGS TO REMEMBER

By the 1970s, ninety percent of able-

bodied women of working age had full- time jobs, giving the Soviet Union the highest rate of female paid employment in the world. By the late 1990s, women made up 70 percent of the registered unemployed, despite the fact that because of illness, death, or divorce, many if not most were the sole support of their families.

The official Soviet ideology was atheism, and religious practice and beliefs were seen as obstacles to revolutionary change. Now, religion is a major component of the general cultural revival across the former Soviet Union.

In Central Asia, Islam was repressed by the Soviets, who feared Islamic fundamentalist movements would cause rebellion against the dominance of Russia. Today, Islam is openly practiced and increasingly important politically across Central Asia, Azerbaijan, and some of the Russian Federation’s internal ethnic republics, such as Chechnya and Tatarstan.