6.3 HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

Often heralded as a “cradle of civilization” and the birthplace of three major world religions, the North Africa and Southwest Asia regions have more recently struggled with the impacts of outsiders. In the current era, social and political change has lagged behind economic development, which itself varies widely around the region. Why has the wealth generated by oil not resulted in a spreading of opportunities, such as broad public education, an opening up of public discourse, and an expansion of educational and political opportunities for women? As indicated in the opening vignette, change is now underway across this region and is gaining momentum, but there are countervailing forces that could inhibit political reform, social change, and economic development.

6.3.1 HUMAN PATTERNS OVER TIME

Important developments in agriculture, societal organization, and urbanization took place long ago in this part of the world. Also, three of the world’s great religions were born here: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Agriculture and the Development of Civilization

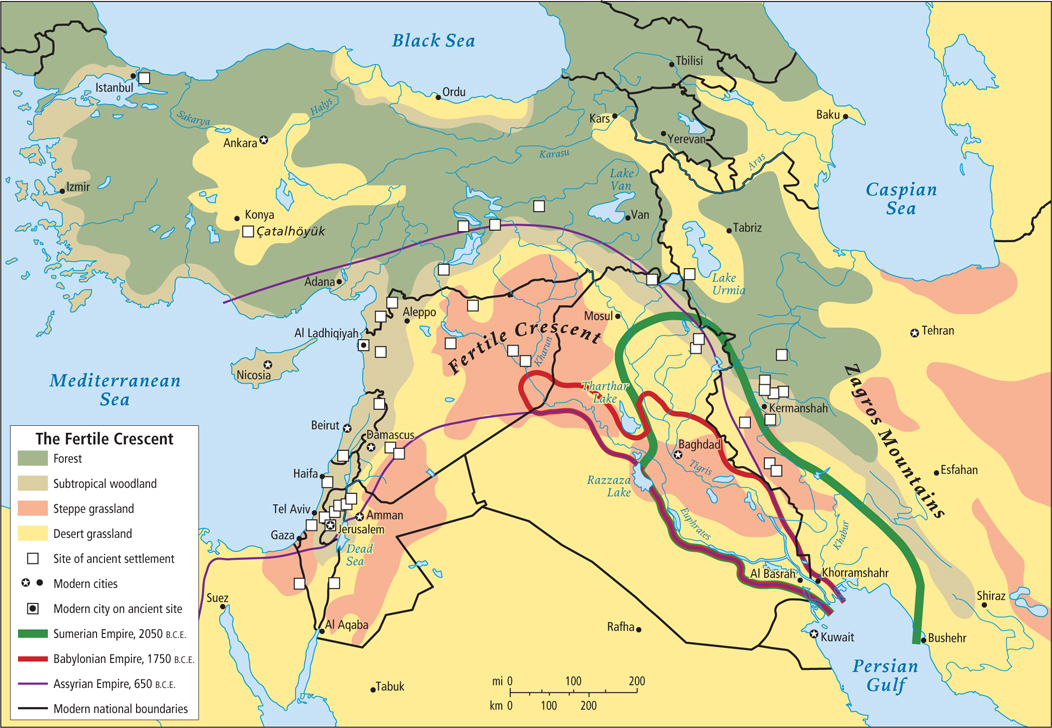

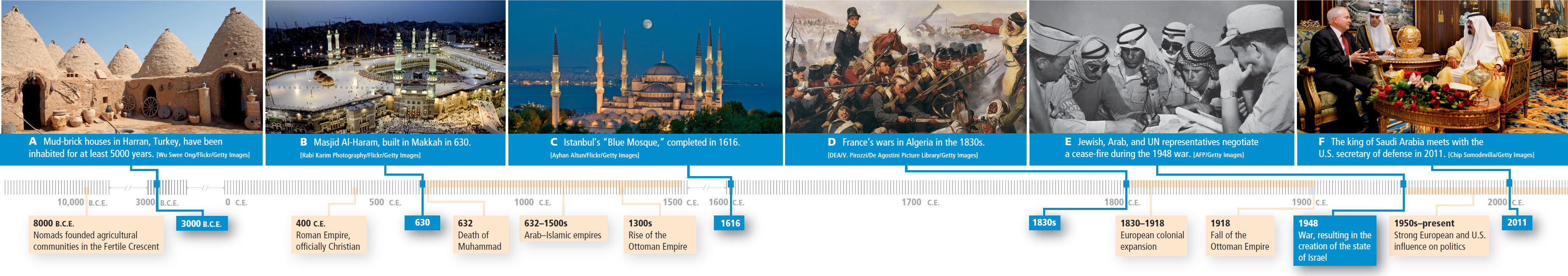

Between 8000 and 10,000 years ago, formerly nomadic peoples founded some of the earliest known agricultural communities in the world. These communities were located in an arc formed by the uplands of the Tigris and Euphrates river systems (in modern Turkey and Iraq) and the Zagros Mountains of modern Iran (see Figure 6.16). This zone is often called the Fertile Crescent because of its once-

Fertile Crescent an arc of lush, fertile land formed by the uplands of the Tigris and Euphrates river systems and the Zagros Mountains, where nomadic peoples began the earliest known agricultural communities

244

The skills of these early people in domesticating plants and animals allowed them to build ever more elaborate settlements. The settlements eventually grew into societies based on widespread irrigated agriculture along the foot of the mountains and in river basins, especially along the Tigris and Euphrates. Nomadic herders living in adjacent grasslands traded animal products for the grain and other goods produced in the settled areas.

Over several thousand years, agriculture spread to the Nile Valley, west across North Africa, north and west into Europe, and east to the mountains of Persia (modern Iran). Ultimately, other cultivation systems across the world were influenced by developments in the Fertile Crescent. Eventually, small settlements associated with agriculture took on urban qualities: dense populations, specialized occupations, concentrations of wealth, and centralized government and bureaucracies. For example, the agricultural villages of Sumer (in modern southern Iraq), which existed 5000 years ago, gradually turned into city-

From time to time, nomadic tribes who had adopted the horse as a means of conquest banded together and, with devastating cavalry raids, swept over agricultural settlements. They then set themselves up as a ruling class, but soon these former nomads adopted the settled ways and cultures of the peoples they conquered and thus themselves became vulnerable to attack.

Agriculture and Gender Roles

Increasing research evidence suggests that the dawning of agriculture may have marked the transition to markedly distinct roles for men and women. Archaeologist Ian Hodder reports that at the 9000-

Scholars think that after the development of agriculture, as the accumulation of wealth and property became more important in human society, concerns about family lines of descent and inheritance emerged. This led in turn to the idea that women’s bodies needed to be controlled so that a woman could not become pregnant by a man other than her mate and thus confuse lines of inheritance. From this core concern about secure lines of descent grew many practices aimed at reinforcing the idea that the mating of women had to be controlled and, by extension, that women’s daily spatial freedom, interaction with men, and sexuality needed to be curtailed.

The Coming of Monotheism: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

The very early religions of this region were founded on a belief in many gods who controlled natural phenomena; such was the case through the Greek era and into the Roman period. Then, several thousand years ago, monotheism—the belief system based on the idea that there is only one god—

monotheism the belief system based on the idea that there is only one god

245

Judaism was founded approximately 4000 years ago. According to tradition, the patriarch Abraham led his followers from Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) to the shores of the eastern Mediterranean (modern Israel and the occupied Palestinian Territories), where he founded Judaism. Judaism is characterized by the belief in one God, a strong ethical code summarized in the Ten Commandments, and an enduring ethnic identity reinforced by dietary and religious laws.

Judaism a monotheistic religion characterized by the belief in one god (Yahweh), a strong ethical code summarized in the Ten Commandments, and an enduring ethnic identity

After rebelling against the Roman Empire, which culminated in their expulsion in 73 c.e. from the eastern Mediterranean, some Jews were enslaved by the Romans and most migrated to other lands in a movement known as the diaspora (the dispersion of an originally localized people). Many Jews migrated across North Africa and Europe, and others went to various parts of Asia. After 1500, Jews were among the earliest European settlers in all parts of the Americas.

diaspora the dispersion of Jews around the globe after they were expelled from the eastern Mediterranean by the Roman Empire beginning in 73 c.e.; the term can now refer to other dispersed culture groups

Christianity is based on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, a Jew who, claiming to be the son of God, gathered followers in the area of Palestine about 2000 years ago. Jesus, who became known as Christ (meaning anointed one or Messiah), taught that there is one God, who primarily loves and supports humans but who will judge those who do evil. This philosophy grew popular, and both Jewish religious authorities and Roman imperial authorities of the time saw Jesus as a dangerous challenge to their power.

Christianity a monotheistic religion based on the belief in the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, a Jew, who described God’s relationship to humans as primarily one of love and support, as exemplified by the Ten Commandments

After Jesus’ execution in Jerusalem in about 32 c.e., his teachings were written down (the Gospels) by those who followed him, and his ideas as interpreted by these writers spread and became known as Christianity. Centuries of persecution ensued, but by 400 c.e., Christianity had become the official religion of the Roman Empire. However, following the spread of Islam after 622 c.e., only remnants of Christianity remained in Southwest Asia and North Africa.

Islam, now the overwhelmingly dominant religion in the region, emerged in the seventh century c.e., after the Prophet Muhammad transmitted the Qur’an to his followers by writing down what was conveyed to him by Allah (“God” in Arabic). Born in about 570 c.e., Muhammad was a merchant and caravan manager in the small trading town of Makkah (Mecca) on the Arabian Peninsula near the Red Sea (see Figure 6.16B). Followers of Islam, called Muslims, believe that Muhammad was the final and most important in a long series of revered prophets, which includes Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.

Muslims followers of Islam

Unlike the many versions of Christianity, Islam has virtually no central administration and only an informal religious hierarchy (this is somewhat less true of the Shi‘ite version of Islam; see the discussion later in this chapter). The world’s one billion Muslims may communicate directly with God (Allah). A clerical intermediary is not necessary, though there are numerous clerical leaders who help their followers interpret the Qur’an. An important effect of the lack of a central authority is that the interpretation of Islam varies widely within and among countries, from group to group, and from individual to individual.

Today, 93 percent of the people in the region are followers of Islam; for them, the Five Pillars of Islamic Practice embody the central teachings of Islam. Not all Muslims are fully observant, but the Pillars have had an enormous impact on daily life, including on festivals and religious holidays, since the time of Muhammad (Figure 6.14).

The Pillars of Muslim Practice

A testimony of belief in Allah as the only God and in Muhammad as his messenger (prophet).

Daily prayer at five designated times (daybreak, noon, midafternoon, sunset, and evening). Although prayer is an individual activity, Muslims are encouraged to pray in groups and in mosques. The call to prayer, broadcast five times a day in all parts of the region, is a constant reminder to all people to reflect on their beliefs.

Obligatory fasting (no food, drink, or smoking) during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan, followed by a light celebratory family meal after sundown. Ramadan falls in the ninth month of the Islamic (lunar) calendar.

Obligatory almsgiving (zakat) in the form of a “tax” of at least 2.5 percent. The alms are given to Muslims in need. Zakat is based on the recognition of the injustice of economic inequity. Although it is usually an individual act, the practice of government-

enforced zakat is returning in certain Islamic republics. Pilgrimage (hajj) at least once in a lifetime to the Islamic holy places, especially the Masjid Al-

Haram and the Kaaba in Makkah (Mecca), during the twelfth month of the Islamic calendar. hajj the pilgrimage to the city of Makkah (Mecca) that all Muslims are encouraged to undertake at least once in a lifetime

Saudi Arabia occupies a prestigious position in Islam, as it is the site of two of Islam’s three holy shrines: Makkah, the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad and of Islam, and Al Madinah (Medina), the site of the Prophet’s mosque and his burial place. (The third holy shrine is in Jerusalem.) The fifth pillar of Islam has placed Makkah and Al Madinah at the heart of Muslim religious geography for more than 1400 years. Today, a large private sector service industry, owned and managed by members of the huge Saud family that rules Saudi Arabia, organizes and oversees the 5-

246

Islamic Religious Law and Variable Interpretations Beyond the Five Pillars, Islamic religious law, called shari‘a, or “the correct path,” guides daily life according to the principles of the Qur’an. But there are many interpretations of the Qur’an, several renderings of shari‘a, and a wide variety of versions of observant Muslim life. Some Muslims believe that no other legal code is necessary in an Islamic society, because shari‘a provides guidance in all matters of life, including worship, finance, politics, marriage, sex, diet, hygiene, war, and crime. Other Muslims think that secular law is more useful in modern societies that are increasingly multicultural because secular law makes allowances for different religious sensibilities. The debate about whether shari‘a or secular law is best has raged for hundreds of years, and recently flared up again as part of the Arab Spring.

shari‘a literally, “the correct path”; Islamic religious law that guides daily life according to the interpretations of the Qur’an

Insofar as the interpretation of shari‘a is concerned, the Muslim community is split into two major groups that formed after the death of Muhammad, when divisions arose over who should succeed the Prophet and have the right to interpret the Qur’an for all Muslims: Sunni Muslims, who today account for 85 percent of the world community of Islam, and Shi‘ite (or Shi‘a) Muslims, who live primarily in Iran but also in southern Iraq, Syria, and southern Lebanon. While Sunnis have a relatively decentralized religious system for interpreting shari‘a, Shi‘ites recognize an authoritative priestly class whom they call mullahs.

Sunni the larger of two major groups of Muslims who have different interpretations of shari‘a

Shi‘ite (or Shi‘a) the smaller of two major groups of Muslims who have different interpretations of shari‘a; Shi’ites are found primarily in Iran and southern Iraq

This division continues today, with disagreements about the interpretation of shari’a exacerbated by countless local disputes over land, resources, and philosophies. In Iraq, for example, long-

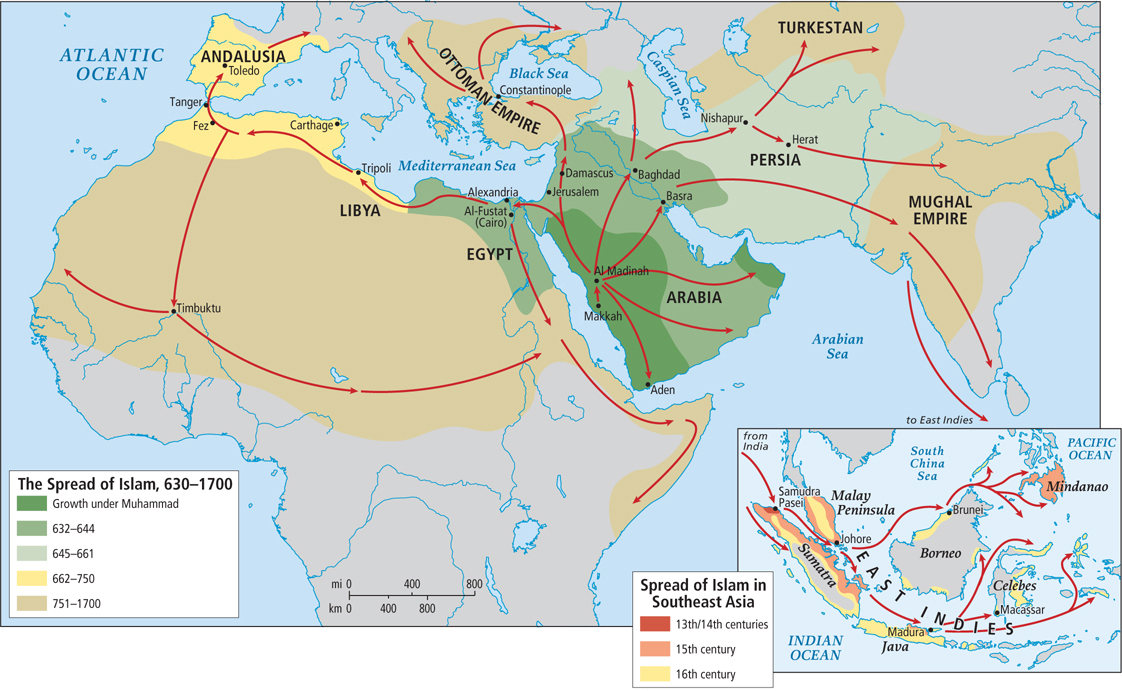

The Spread of Islam

Among the first converts to Islam were the Bedouin—

While most of Europe was stagnating during the medieval period (450–

247

By the end of the tenth century, the Arab–

Ottoman Empire the most influential Islamic empire the world has ever known; begun in the 1200s when nomadic Turkic herders from Central Asia converged in western Anatolia (Turkey)

By the 1300s, the Ottomans had become Muslim and by the 1400s they had defeated the Christian Byzantine Empire centered in Constantinople, which was the successor to the Roman Empire. The Ottomans took over Constantinople, renamed it Istanbul, and soon controlled most of the eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. By the late 1400s, they also controlled much of southeastern and central Europe and by the 1600s had taken over parts of coastal North Africa from the Arabs. Previously, in the 1490s, the Arab Muslims had lost their control of the Iberian Peninsula to Christian kingdoms. Islam currently still dominates in a huge area that stretches from Morocco to western China and includes northern South Asia, as well as Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia in Southeast Asia (see the inset of Figure 6.15).

Once a location was completely conquered, the Ottoman Empire, like the Arab–

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Visual History above to answer these questions.

Scroll to see the full graphic.

Question 6.6

H5E+xeKlAQH2+onGPQb9uZvqzteEleWUNOxZDx+D/qIkLD4U0gJzNxTNvQHm8+bUFwJiWKia1CYmgPDpO0cOBiQ+VRYmDt7/pV5zDooi7u7KPUkxQuestion 6.7

OKLe/dt/gvJiX8xHPUrTI+mncLFUXBoj0yWDPaRmA1l1MZxVzBZu2daWEDocdcufuM9MPaLNoxu9z8776sXCq/aQgKlud3dAiQPLBxzLB0etH0PMjmRUspRgSY+8H7FTk1/27fX7wo5rhwteEK0+WzTFKzGcCZuPgyiGRUWvfwdrn+vm4pLvJDOF0skCK0aeYcP1SqfFcMk=Question 6.8

svx/6VCWP9B746hInn65MMUkNKA74/r8NJ6bQjJ+z/cj4X02ewXigef0epbjm6IEX3ceq5E+1VF2zLey+abjPZ9lW5uhR0BUoW0S44mCSb7SR9NEBCcmBFbRQCuMlk5aLOIpjj4qfiR4+2TOGc3Zj4Y+dVmwTQ4DGPgoXx16WyjkKBZRWdqyBg==Question 6.9

G8jWT4jqwdziLzeaPgNptt79CLncoNOqp/00qrdVnZ81VlpQPJPinlIxih7y73UIHH0vRAVUkQPAOetIz3RjMePDSOjZ8Yt7LabRQZLl04wUdgyOio6j0EaeFMQ9swsamad0JA==Question 6.10

lCTY8kObwoF+gbRNN9ck+iF3DQyxThjGxoT4aKBTewRBg6OHVr+SlIWO5ZeaYVzxXnzK7tqAky7HhiCi9ev9pMsqZROL6KKBbpY2Ljp3LoEQ5CwUbYr7euCFO8mLPIxsDQvq8cJphAvqE+JoQuestion 6.11

P+FvKfJaxpyUWsNbbDTiTrKZKAiCbeynIEBuY5nG1yvFWlbBUfL3cTUBX89GMOFUawxISHNzYDeBDi/ZqgjuTynd/9+uig248JVUgmMITpyEoecwLFB8Y8Hi3OapCtE5ThgOpgLE6/4cZBLqjJbhtNV3qJzWZz7HWestern Domination, State Formation, and Antidemocratic Practices

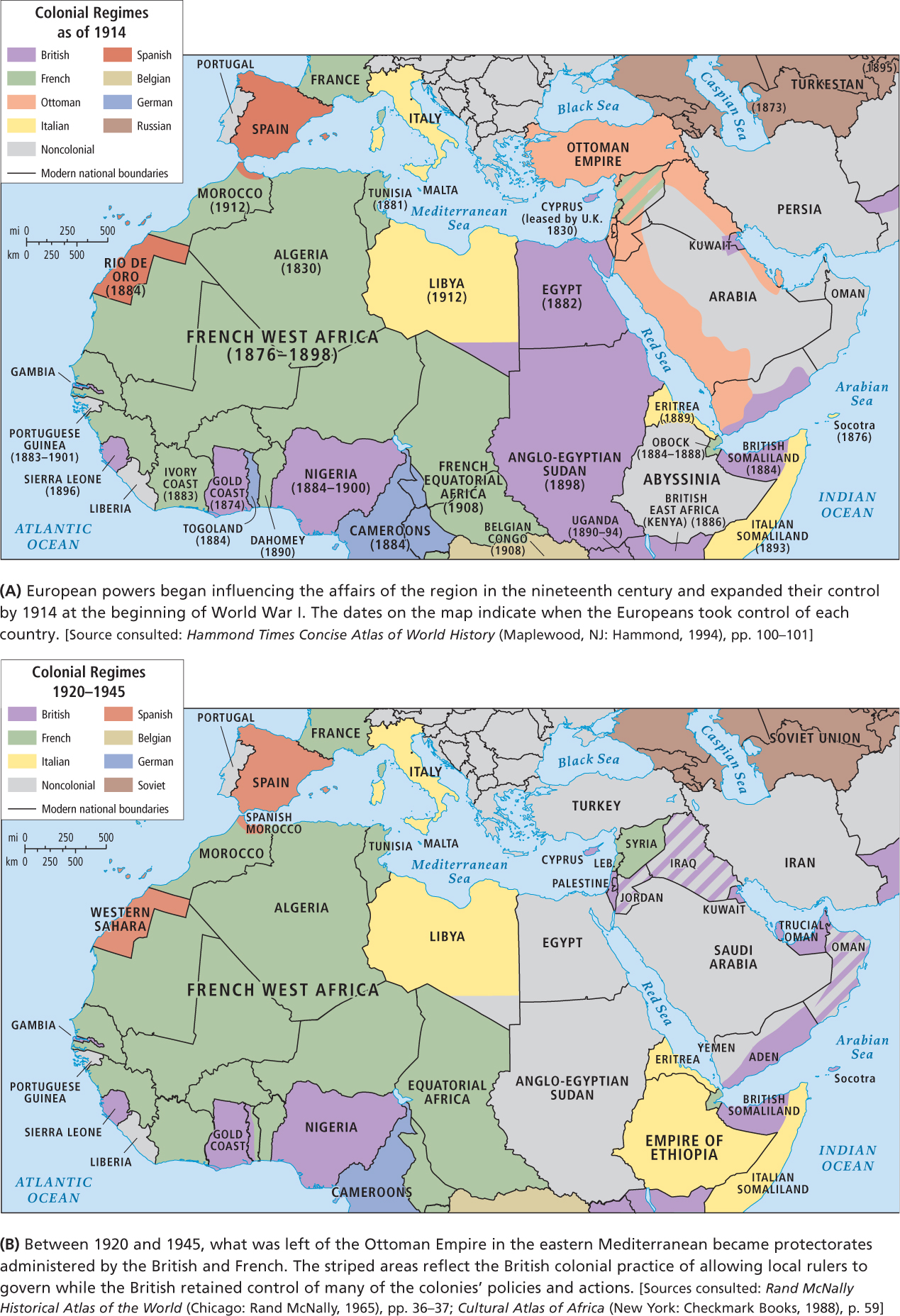

The Ottoman Empire ultimately withered in the face of a Europe made powerful by colonialism and the Industrial Revolution. Throughout the nineteenth century, North Africa provided raw materials for Europe in a trading relationship dominated by European merchants. By 1830, France was exercising direct control over parts of the North African territory of Algeria (see Figure 6.16D). France took control of Tunisia in 1881 and Morocco in 1912 (Spain controlled a bit of the Mediterranean coast and what is now called Western Sahara); Britain gained control of Egypt in 1882 and Sudan in 1898; and Italy took control of Libya in 1912 (Figure 6.17A).

248

World War I (1914–

World War II (1939–

By the 1950s, European and U.S. energy companies played a key role in influencing who ruled Iran and Saudi Arabia—

THINGS TO REMEMBER

About 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent, formerly nomadic peoples founded some of the world’s earliest known agricultural communities. The domestication of plants and animals allowed them to build ever more elaborate settlements that eventually grew into societies that were based on widespread irrigated agriculture.

The three major monotheistic world religions—

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam— all have their origins in this region in the eastern Mediterranean. Islam is by far the largest in numbers of adherents in the region, and it is the principal faith in all of the region’s countries except Israel. For Muslims (93 percent of the population in this region), the Five Pillars of Islamic Practice embody the central teachings of Islam. Some Muslims are fully observant, some are not; but the Pillars have had an impact on daily life for 1400 years.

Beginning in the nineteenth century and continuing through the end of World War II, European colonial powers ruled or controlled most countries in the region.

Following World War II, the state of Israel was created, and in countries with oil deposits and other useful assets, the United States and Western Europe supported those autocratic local leaders who were most likely to maintain a friendly attitude toward U.S. and European business and geopolitical strategic interests.

249