7.8 SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES

To the casual observer, it may appear that a majority of sub-

310

Gender Issues

Long-

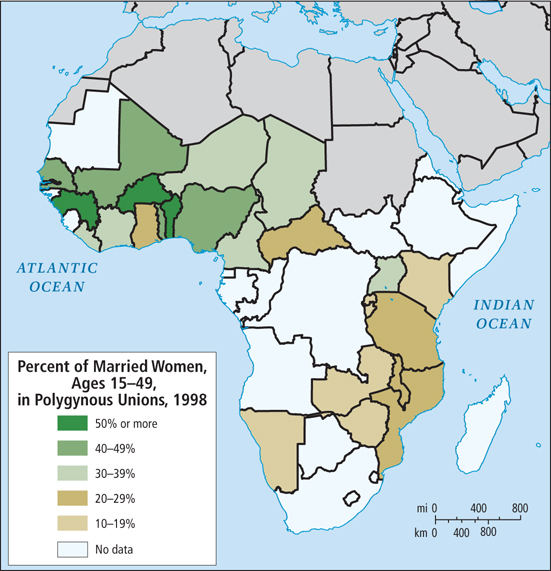

Ideas in Africa about how males and females should relate to each other come from a variety of sources. Even in the ancient past, social controls tempered gender relationships. Most marriages were social alliances between families; therefore, husbands and wives spent most of their time doing their tasks with family members of their own sex rather than with each other. Then as today, women primarily influenced other women and men influenced men. It is important to note that having multiple wives—

polygyny the practice of having multiple wives

Women face significant sexual and physical abuse in the home and during civil unrest, when rape and beatings are more common. Many of the female politicians who have come to power in the last decade are now addressing these issues. Most have emphasized the need for more women to be in the position to influence and enforce policies to reduce violence against women. In Liberia, for instance, President Ellen Johnson-

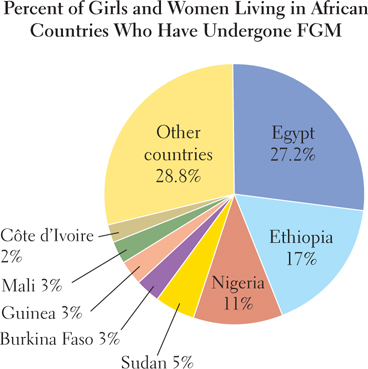

A practice known as female genital mutilation (FGM) (formerly called female circumcision) has been documented in 27 countries in the central portion of the African continent (Figure 7.28). It also is known in Yemen, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Israel, Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates, and, in some cases, in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The practice predates Islam and Christianity, and is performed today among all social classes and in Christian, Muslim, and animist (see the definition later in this chapter) religious traditions. In the procedure, which is usually performed without anesthesia, a young girl’s entire clitoris and parts of her labia are removed. In the most extreme cases (called infibulation), her vulva is stitched nearly shut. This mutilation far exceeds that of male circumcision, eliminating any possibility of sexual stimulation for the female and making urination and menstruation difficult. Intercourse is painful and childbirth is particularly devastating because the flesh scarred by the mutilation is inelastic. A 2006 medical study conducted with the help of 28,000 women in six African countries showed that women who had undergone FGM were 50 percent more likely to die during childbirth, and their babies were at similarly high risk. The practice also leaves women exceptionally susceptible to infection, especially HIV infection.  171. FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION STILL COMMON IN SOMALILAND

171. FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION STILL COMMON IN SOMALILAND

female genital mutilation (FGM) removing the labia and the clitoris and sometimes stitching the vulva nearly shut

The practice is probably intended to ensure that a female is a virgin at marriage and that she has a low interest in intercourse other than for procreation thereafter. While in decline today, FGM is still widespread among some groups. Among the Kikuyu of Kenya, nearly all females would have had FGM 40 years ago, but today only about 40 percent do. Kikuyu women’s rights leaders have had some success in curbing FGM by replacing it with right-

311

Many African and world leaders have concluded that the practice is an extreme human rights abuse, and it is now against the law in 16 countries. The most successful eradication campaigns are those that emphasize the threat FGM poses to a woman’s health, thus making it socially acceptable to not undergo this ritual. The World Health Organization in 2008 took a strong stand against FGM, saying:

Female genital mutilation has been recognized as discrimination based on sex because it is rooted in gender inequalities and power imbalances between men and women and inhibits women’s full and equal enjoyment of their human rights. It is a form of violence against girls and women, with physical and psychological consequences.

World Health Organizations, Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation—

(Geneva: World Health Organization Press, 2008), p. 10.

Religion

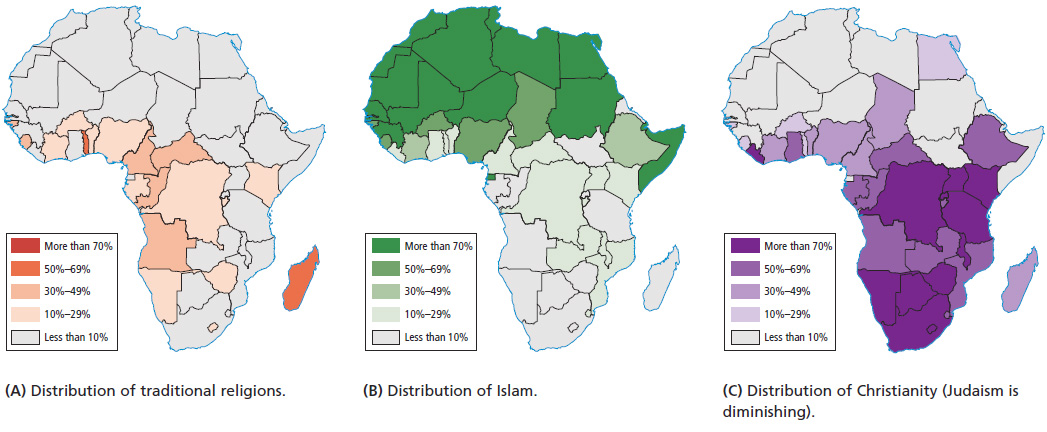

Africa’s rich and complex religious traditions derive from three main sources: indigenous African belief systems (many of them animist), Islam, and Christianity.

Indigenous Belief Systems Traditional African religions, found in every part of the continent, may be the most ancient on Earth, since this is where human beings first evolved. Figure 7.29 highlights the countries in which traditional beliefs remain particularly strong. Traditional beliefs and rituals often are used to bring departed ancestors into contact with living people, who in turn are the connecting links in a timeless spiritual community that stretches into the future. The future is reached only if family members procreate and perpetuate the family heritage through storytelling.

312

Most traditional African beliefs can be considered animist in that spirits, including those of the deceased, are thought to exist everywhere—

animism a belief system in which spirits, including those of the deceased, are thought to exist everywhere and to offer protection to those who pay their respects

Religious beliefs in Africa, as elsewhere, continually evolve as new influences are encountered. If Africans convert to Islam or Christianity, they commonly retain aspects of their indigenous religious heritage. The three maps in Figure 7.29 show a spatial overlap of belief systems, but they do not convey the philosophical blending of two or more faiths, which is widespread. In the Americas, the African diaspora has influenced the creation of new belief systems developed from the fusion of Roman Catholicism and African beliefs. Voodoo in Haiti, Santería in Cuba, and Candomblé in Brazil (see Chapter 3) are examples of this fusion.

Islam and Christianity Islam began to extend south of the Sahara in the first centuries after Muhammad’s death in 632 c.e., and today, about one-

Today, about half of Africans are Christian. Christianity first came to the region via Egypt and Ethiopia shortly after the time of Christ, well before it spread throughout Europe (see Figure 7.29C). Christianity did not come to the rest of Africa until nineteenth-

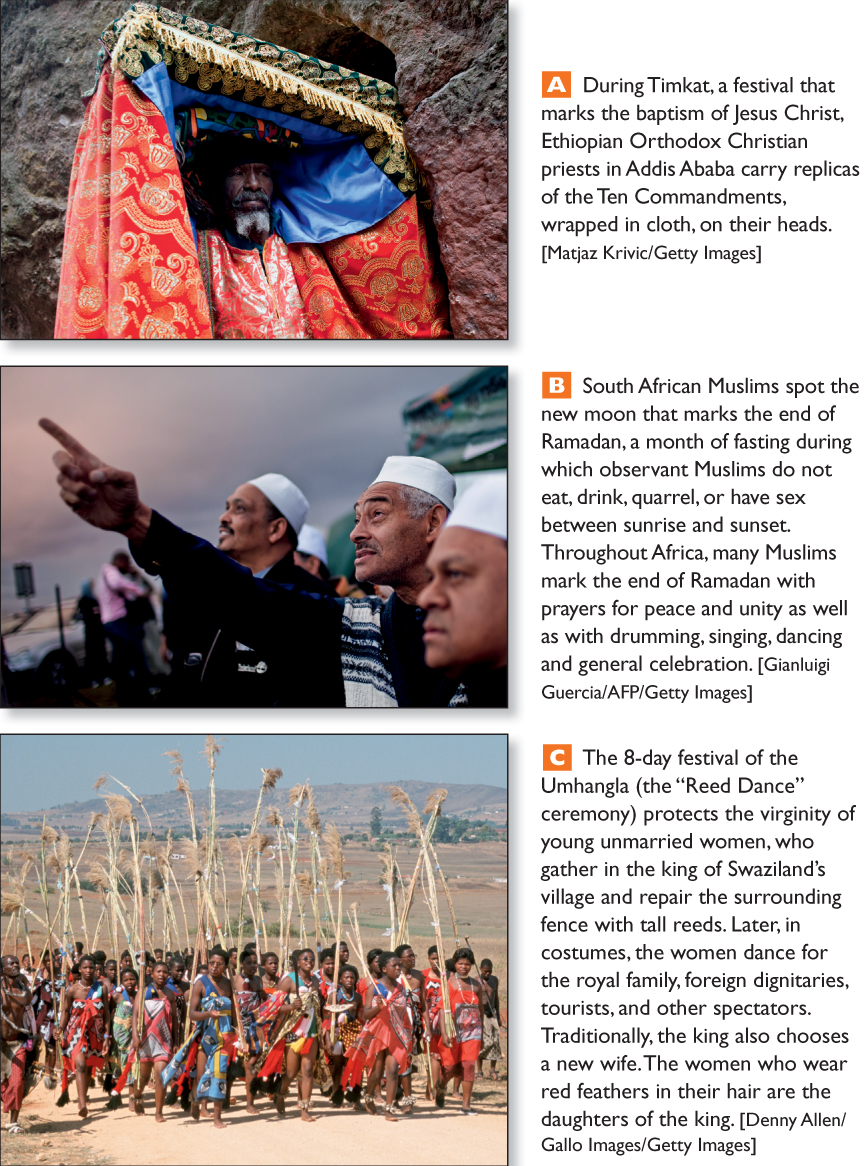

Festivals across the continent celebrate the variety of African religious traditions. As is the case with festivals everywhere, such events offer an opportunity to represent ideal versions of culture, a chance to revel in joy and renewed religious dedication, and a chance to make important social contacts, reinforce identity, and perform community service (Figure 7.30).

Evangelical Christianity and the Gospel of Success In contrast to the Anglican Church, modern evangelical versions of Christianity appeal to the less-

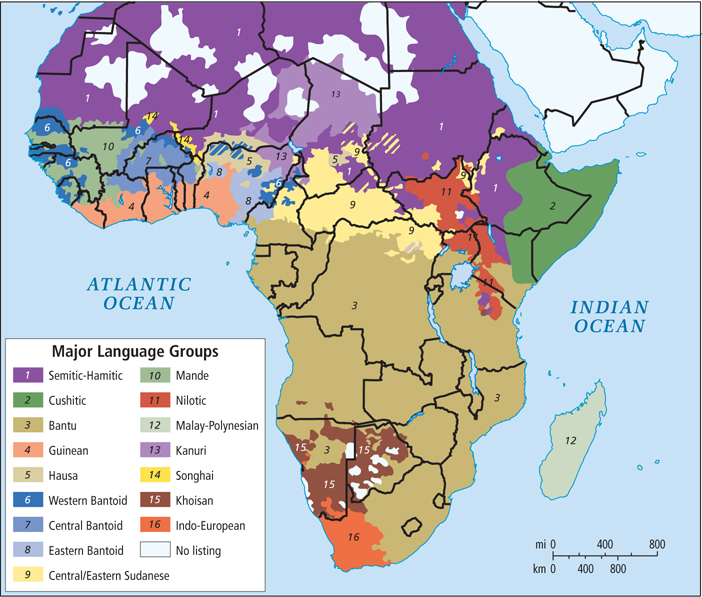

Ethnicity and Language Ethnicity, as we have seen throughout this book, refers to the shared language, cultural traditions, and political and economic institutions of a group. The map of Africa in Figure 7.31 shows a rich and complex mosaic of languages. Yet despite its complexity, this map does not adequately depict Africa’s cultural diversity (compare it with Figure 7.20 of Nigeria).

Most ethnic groups have a core territory in which they have traditionally lived, but very rarely do groups occupy discrete and exclusive spaces. Often several groups share a space, practicing different but complementary ways of life and using different resources. For example, one ethnic group might be subsistence cultivators, another might herd animals on adjacent grasslands, and a third might be craft specialists working as weavers or metalsmiths.

313

People may also be very similar culturally and occupy overlapping spaces but identify themselves as being from different ethnic groups. Hutu farmers and Tutsi cattle raisers in Rwanda share similar occupations, languages, and ways of life. However, European colonial policies purposely exaggerated ethnic differences as a method of control, assigning a higher status to the Tutsis. Hutu and Tutsi now think of themselves as having very different ethnicities and abilities. In the 1990s and again in 2004, the Hutu-

VIGNETTE

Preachers at the Miracle Center in Kinshasa describe the Gospel of Success forcefully: “The Bible says that God will materially aid those who give to Him. . . We are not only a church, we are an enterprise. In our traditional culture you have to make a sacrifice to powerful forces if you want to get results. It is the same here.”

Generous gifts to churches are promoted as a way to bring divine intervention to alleviate miseries, whether physical or spiritual. Practitioners donate food, television sets, clothing, and money. One woman gave 3 months’ salary in the hope that God would find her a new husband.

Like all religious belief systems, the Gospel of Success is best understood within its cultural context. Many of the believers new to the city feel isolated and are looking for a supportive community to replace the one they left behind. In return for material contributions to the church and volunteer services, members receive social acceptance and community assistance in times of need.

Some African countries have only a few ethnic groups; others have hundreds. Cameroon, sometimes referred to as a microcosm of Africa because of its ethnic complexity, has 250 different ethnic groups. Different groups often have extremely different values and practices, making the development of cohesive national policies difficult. Nonetheless, the vast majority of African ethnic groups have peaceful and supportive relationships with one another.

To a large extent, language correlates with ethnicity. More than a thousand languages, falling into more than a hundred language groups, are spoken in Africa; Bantu is the largest such group (see Figure 7.31). Most Africans speak their native tongue and a lingua franca (language of trade). Some languages are spoken by only a few dozen people, while other languages, such as Hausa, are spoken by millions of people from Côte d’Ivoire to Cameroon. Lingua francas—

lingua franca a language of trade

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Gender relationships in sub-

Saharan Africa are complex and variable, but in this region as in others, women are generally subordinate and are often physically abused. Nevertheless, change is underway. Female genital mutilation has terrible consequences for women’s health. It has been recognized as sexual discrimination because it is rooted in gender inequalities and power imbalances between men and women.

Traditional African religions are among the most ancient on Earth and are found in every part of the continent. Today, however, about one-

third of sub- Saharan Africans are Muslim and about half are Christian. Many in the evangelical movement, a subset of Christianity, promote the Gospel of Success as a way of life. Sub-

Saharan Africa is a mosaic of more than 1000 languages that are roughly similar to the mosaic of ethnic groups. Hausa, Arabic, and Swahili are now the most commonly used languages of trade. 3

314