8.1 Chapter 8 SOUTH ASIA

316

317

chapter 8

SOUTH ASIA▶

318

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHTS: SOUTH ASIA

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the five thematic concepts:

|

1. |

Environment: |

Climate change puts more lives at risk in South Asia than in any other region in the world, primarily due to water- |

|

2. |

Globalization and Development: |

Globalization benefits some South Asians more than others. Educated and skilled South Asian workers with jobs in export- |

|

3. |

Power and Politics: |

India, South Asia’s oldest, largest, and strongest democracy, has shown that the expansion of political freedoms can ameliorate conflict. Across the region, when people have been able to participate in policy- |

|

4. |

Urbanization: |

South Asia has two general patterns of urbanization: one for the rich and the middle classes and one for the poor. The areas that the rich and the middle classes occupy include sleek, modern skyscrapers bearing the logos of powerful global companies, universities, upscale shopping districts, and well- |

|

5. |

Population and Gender: |

In this most densely populated of world regions, population growth is slowing as the demographic transition takes hold. Birth rates are falling due to rising incomes, urbanization, better access to health care, and the fact that women are finding more opportunities to study and work outside the home, and thus are delaying childbearing and having fewer children. However, a severe gender imbalance is developing in this region due to age- |

The South Asian Region

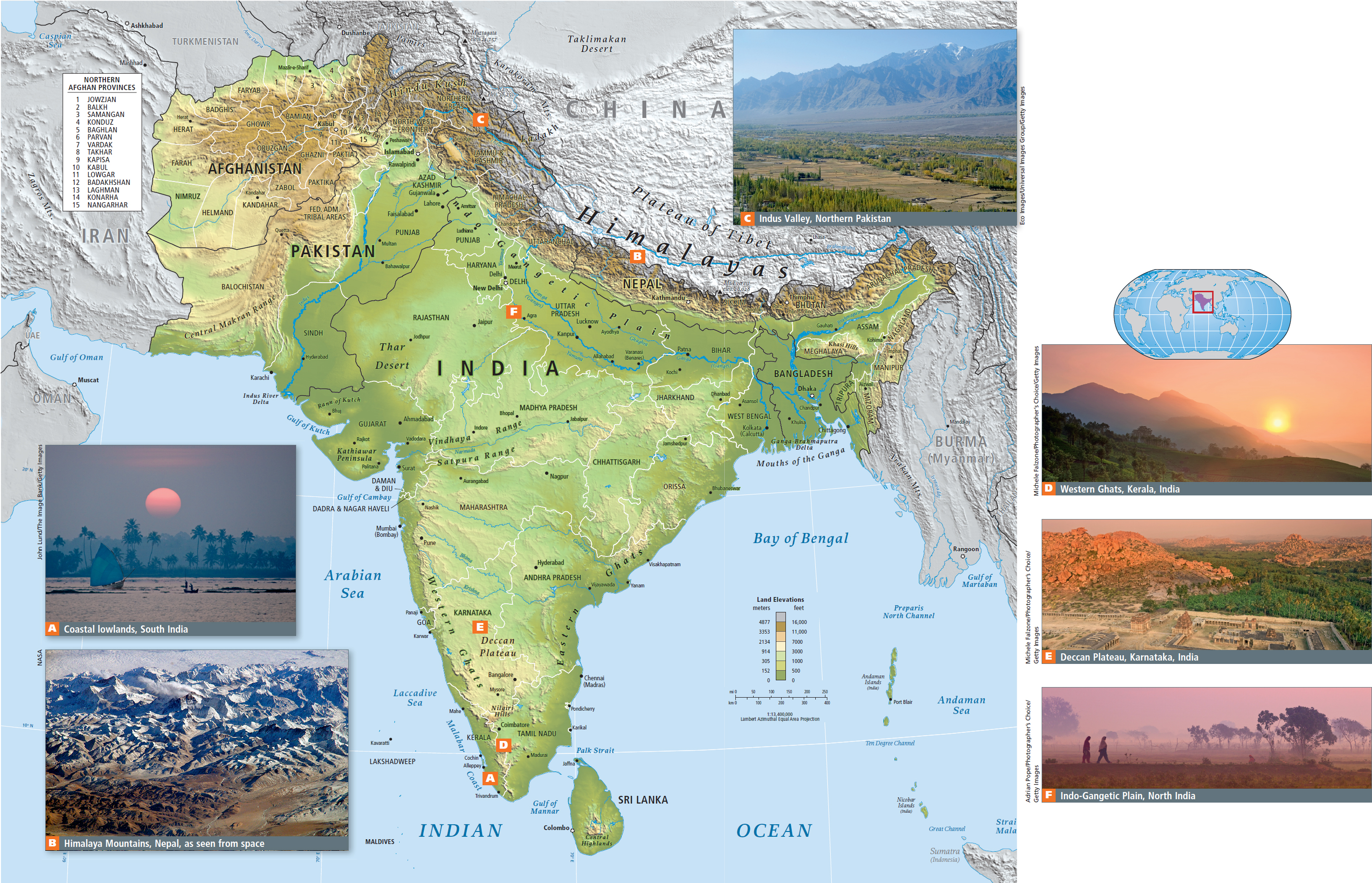

South Asia (Figure 8.1), like so many of today’s world regions, began its modern history as the result of European colonization. During that time, economic, political, and social policies rarely put the needs of South Asian people first. Toward the end of the colonial era, major upheavals precipitated by departing colonists left the region with a legacy of distrust and difficult political borders that still lingers.

The five thematic concepts highlighted in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues, with interactions between two or more themes featured, as in the geographic insights above. Vignettes, like the one that follows, illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

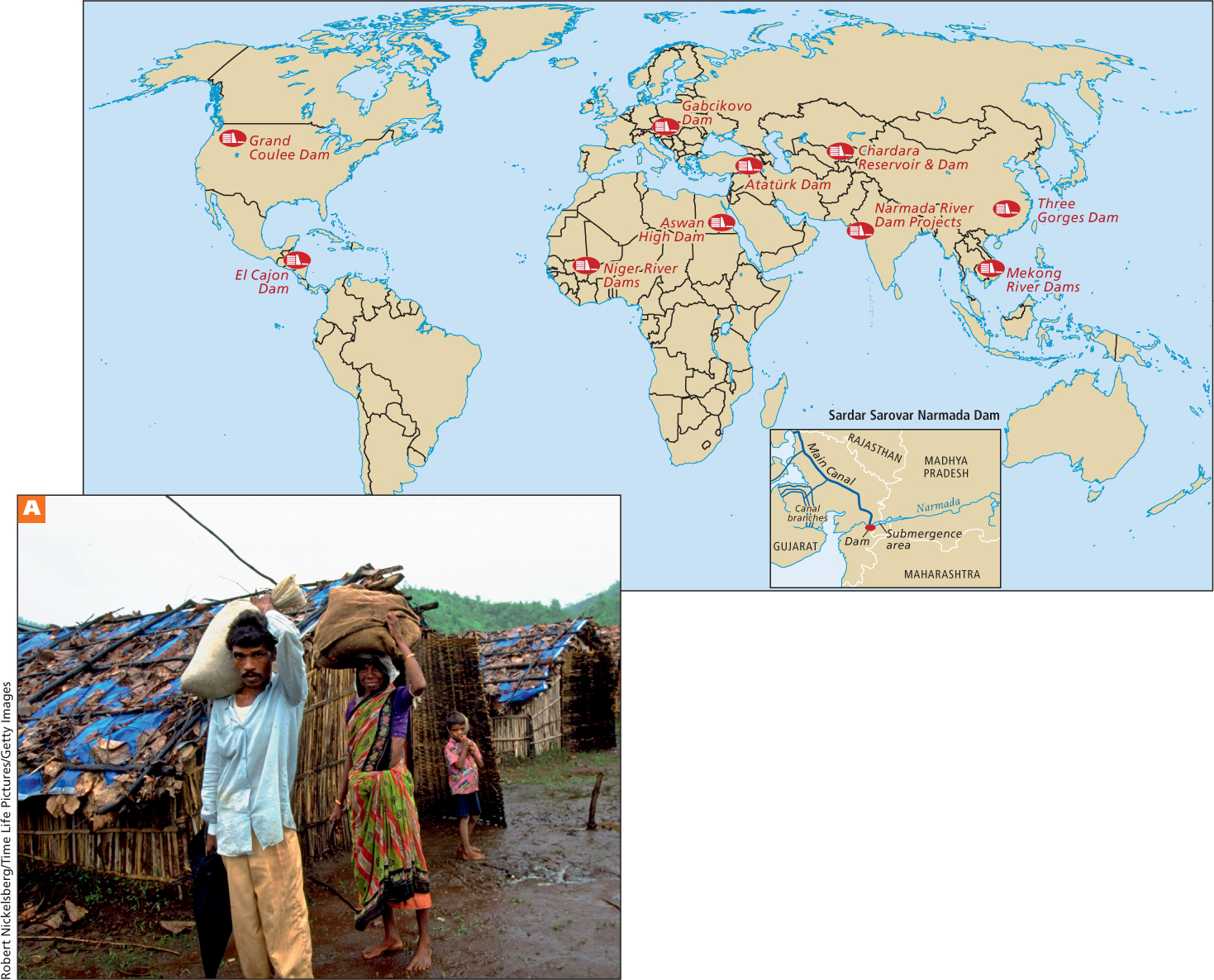

Narendra Modi, the chief minister of the state of Gujarat in western India (see Figure 8.1), is passionate about securing water for his state. In 2006, draped in garlands by well-

At the same time as Modi’s hunger strike, far away in New Delhi, Medha Patkar, the leader of the “Save the Narmada River” movement, was in day 18 of her hunger strike protesting against the same dam. As water rose in the dam’s reservoir, 320,000 farmers and fishers in Madhya Pradesh, the state in which the reservoir is located, were being forced to move. Although Indian law requires that these “evacuees” be given land or cash to compensate them for what they had lost, only a fraction had received any compensation. Some of the evacuees demonstrated their objection by forfeiting their right to compensation and refusing to move even as the rising waters of the reservoir consumed their homes. Many were forcibly removed by Indian police and have since relocated to crowded urban slums.

Environmental and human rights problems have been at the heart of the Sardar Sarovar Dam controversy since the project began in 1961. The natural cycles of the Narmada River have been severely disturbed. Once a placid, slow-

319

In addition to cost overruns that are more than three times the original cost estimates, the ultimate benefits of the dam have been called into question. A major justification for the dam was that in addition to irrigation water, it would provide drinking water for 18 million people in the greater river basin as well as 1450 megawatts of electricity. But the demand for irrigation waters to serve drought-

Concerned that the economic benefits would be small and easily negated by the environmental costs, the World Bank withdrew its funding of the dam some years ago. Ecologists say that far less costly water-

Minister Modi quickly ended his hunger strike when the Indian Supreme Court ruled that the Sardar Sarovar Dam could be raised higher (it now stands at 121.92 meters, or 400 feet). The following day, Medha Patkar ended her fast as well, because, in the same decision, the Supreme Court ruled that all people displaced by the dam must be adequately relocated. Furthermore, the court decision confirmed that human impact studies are required for all dam projects. Up to then, no such study had been done for the Sardar Sarovar Dam. Nonetheless, by September of 2012, the dam project was 8 years behind schedule and had stalled again in court. Both sides used the Internet to promote their positions. Meanwhile, Narendra Modi achieved national prominence and began an unsuccessful campaign to be elected prime minister of India. [Sources: India eNews; Frontline; Friends of River Narmada (http:/

320

The recent history of water management in the Narmada River valley highlights some key issues now facing South Asia and other regions that have developing economies. Across the world, large, poor populations depend on increasingly overtaxed environments. Improving the standard of living for the poor nearly always requires increases in water and energy use. Often, misplaced efforts to meet these urgent needs make neither economic nor environmental sense, but are driven to completion by political and social pressures. In the case of the Sardar Sarovar Dam, the wealthier, more numerous, and more politically influential farmers of Gujarat have tipped the scale—

The role of water in South Asian life, including the ways water use intersects with other central issues, is a recurring topic in this chapter.

What Makes South Asia a Region?

The countries that make up the South Asia region in this book are Afghanistan and Pakistan in the northwest; the Himalayan states of Nepal and Bhutan; Bangladesh in the northeast; India (including the Indian territories of Lakshadweep, Andaman, and Nicobar Islands); and the island countries of Sri Lanka and the Maldives (Figure 8.3; see also Figure 8.1). Physically, these countries occupy territory known as the Asian subcontinent—the portion of a tectonic plate that joined the Eurasian continent nearly 60 million years ago (discussed below). Historically and culturally, these modern countries have a shared patchwork of religious, social, and political features linked to ancient conquerors from Central Asia, explorers and traders from the Arabian Peninsula and Southeast Asia, and more recent colonizers from Europe. This region can be compared to a patchwork, as its extensive history of internal and external influences has left it with a fragmented and overlapping pattern of religions, languages, ethnicities, economic theories, forms of government, attitudes toward gender and class, and ideas about land and resource use.

Terms in This Chapter

Because its clear physical boundaries set it apart from the rest of the Asian continent, the term subcontinent is often used to refer to the entire Indian peninsula, which includes Nepal, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh (the term usually does not include Afghanistan).

subcontinent a term often used to refer to the entire Indian peninsula, including Nepal, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh

South Asians have recently adopted new place names to replace the names given them during British colonial rule. The city of Bombay, for example, is now officially Mumbai, Madras is Chennai, Calcutta is Kolkata, Benares is Varanasi, and the Ganges River is the Ganga River.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The Sardar Sarovar Dam and similar dams throughout the world are created primarily for irrigation and power generation, but they have side effects that often create more problems than they solve.

The management of water—

where it is apportioned and whether there is too much or too little of it— has been a feature of South Asian life for a long time. Climate change now makes water management more problematic. Improving the standard of living of poor populations in many parts of the world nearly always requires increases in water and energy use.