9.1 Chapter 9 EAST ASIA

360

361

chapter 9

EAST ASIA▶

362

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHTS: EAST ASIA

After you read this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following geographic insights as they relate to the five thematic concepts:

|

1. |

Environment: |

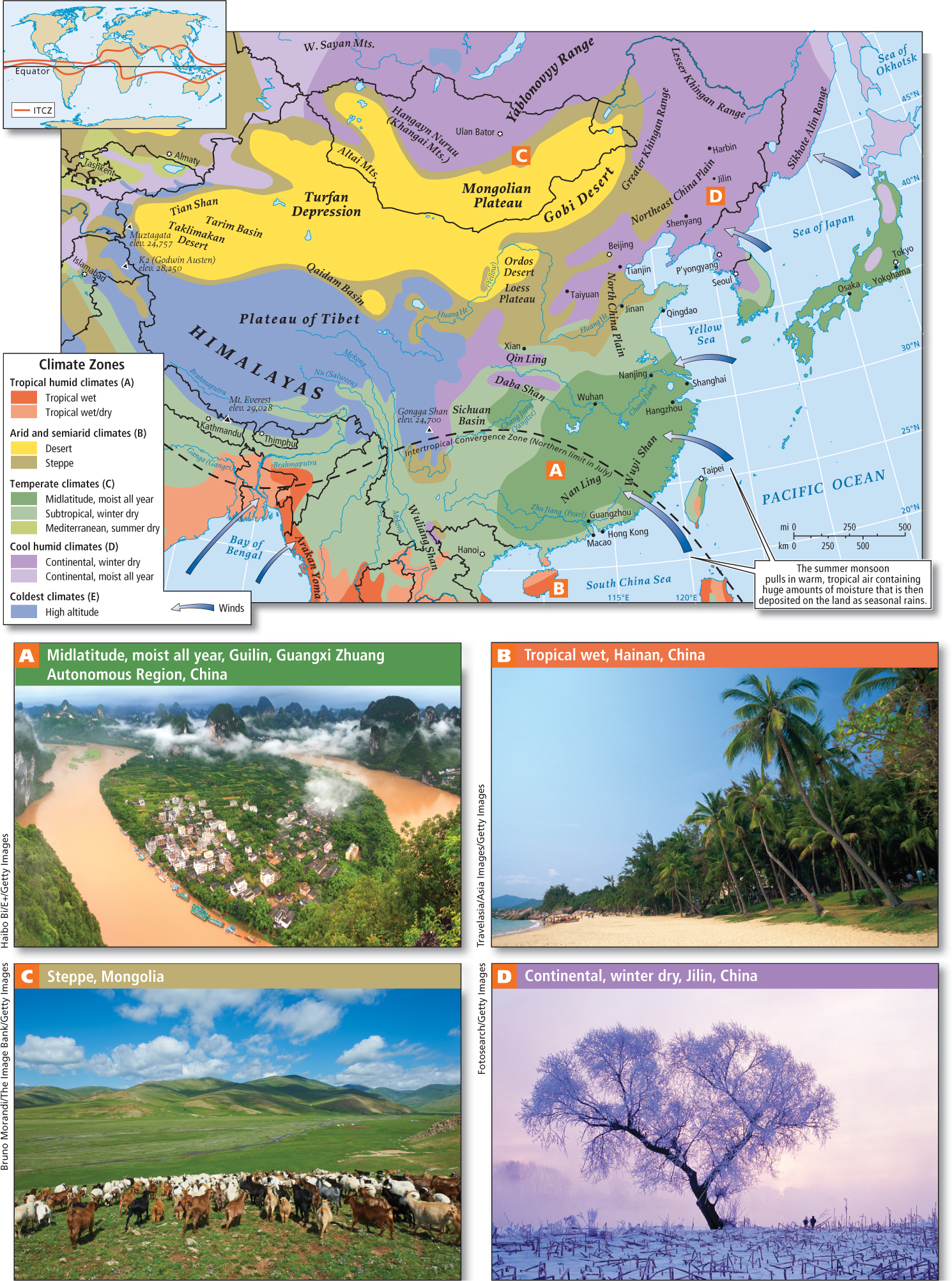

East Asia’s most serious environmental problems result from its high population density combined with its rapid urbanization and environmentally unsustainable economic development. Climate change may intensify the droughts and floods that have long plagued this region. |

|

2. |

Globalization and Development: |

East Asia pioneered a spectacularly successful economic development strategy that has transformed economies across the globe. Governments in Japan and then Taiwan, South Korea, and eventually China intervened strategically in the economy to encourage the production of manufactured goods destined for sale abroad, primarily to the large economies of North America and Europe. |

|

3. |

Power and Politics: |

As East Asia has developed economically, the pressure for more political freedoms has grown. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are now among the more politically free places in the world, and demands for political change in China are increasing, especially in urban areas. |

|

4. |

Urbanization: |

Across East Asia, cities have grown rapidly over the last century, fueled by export- |

|

5. |

Population and Gender: |

Although East Asia remains the most populous world region, families here are having far fewer children than in the past, resulting in populations that are aging. Meanwhile, the legacy of China’s now largely abandoned “one child” policy, combined with an enduring cultural preference in China for male children, has created a shortage of females. |

The East Asia Region

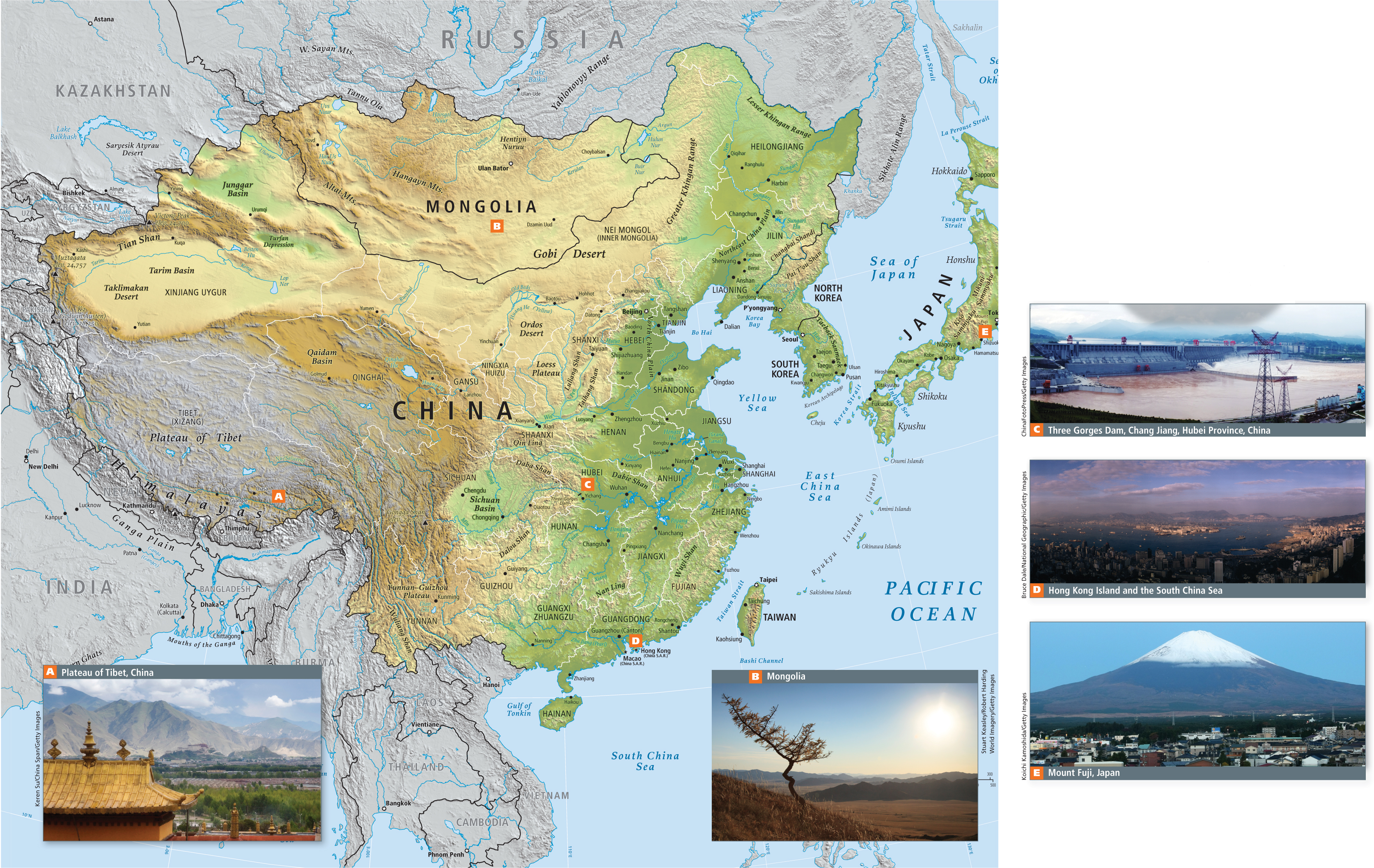

East Asia (Figure 9.1), with 1.6 billion people, is the most populous world region. The region is dominated by China, which has a population of 1.35 billion. China’s dominance is not due only to its population, but also to its physical size and its economic role in the global economy. Just as the striking economic rise of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan has been the model for developing countries over the past 50 years, the opening of China to the global economy will continue to transform East Asia and the world for 50 years or more. The changes underway in this region today are immense. Incomes have risen and cities have boomed, but so have air and water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, there are signs that new, cleaner technologies may mitigate these pollution problems.

The five thematic concepts in this book are explored as they arise in the discussion of regional issues, with interactions between two or more themes featured. Vignettes, like the one that follows about the situation of workers in the East Asian economy, illustrate one or more of the themes as they are experienced in individual lives.

GLOBAL PATTERNS, LOCAL LIVES

In 2000, at age 18, Li Xia (Li is her family name) left her farming village in China’s Sichuan Province (Figure 9.2A) for Dongguan, then a city of 6.4 million, in the Guangdong Province of southern China. She was accompanied by two friends. A few months earlier, the government had taken their families’ farmland for an urban real estate project, paying compensation of only U.S.$2000 per family. The three young women accepted an offer to work in a Dongguan toy factory so they could send money back to their families, who now have to pay cash for food and housing (see Figure 9.2B).

When the young women arrived in the city, they joined 4.3 million other recent internal migrants, who formed 63 percent of Dongguan’s population. Like Li Xia, they had migrated illegally without government-

Xia felt better when she saw that the toy factory was a clean, modern building known locally as the “Palace of Girls” (nearly all 3500 employees were female). Within a day, she had completed her training, signed a 3-

363

After her contract was up, Xia returned home to her village in Sichuan. There, using ideas and assertiveness she had gained from her time in Dongguan, she opened a snack stand. In just 1 month, she made ten times her investment of U.S.$12. But this was still less than she could earn in the city, so after a year Xia returned to Dongguan to try again for a well-

Since her first arrival, the city had grown by 20 percent and now had 1400 foreign companies trying to hire thousands of workers.

Through connections, Xia and her sister found jobs requiring midlevel skills in a Taiwanese-

[Sources: Washington Post, National Public Radio, and Wall Street Journal. For detailed source information, see Text Sources and Credits.]

The experiences of Li Xia illustrate first how the needs of rural areas are being subverted to the needs of China’s burgeoning cities. Developers are increasingly targeting rural land, and farmers are rarely given a fair price for their land. The reason for this is that the individual Chinese farmer does not own farmland; he or she only leases it from the local government, which may be inclined to sell the land to high-

Urbanization, globalization, and changes in gender roles are transforming East Asia as millions of rural young adults are flocking to East Asia’s coastal cities to work in factories. There they produce goods for sale on global markets, learn new skills, and gain new confidence (see the Figure 9.2 map).

Until 2014, most rural-

hukou system the system in China that ties people to their place of birth; each person’s permanent residence is registered and any person who wants to migrate must obtain permission from authorities to do so

floating population the Chinese term for people who live in a place other than their household registration location; many are jobless or underemployed people who have left economically depressed rural areas for the cities

364

For decades, the Chinese government only weakly enforced the hukou system because urban industries were in need of a growing workforce. The lax enforcement enabled the mobility of the labor force while keeping that labor vulnerable and exploitable. The current reforms to the hukou system are designed both to encourage more migration to cities, which have had labor shortages in recent years, and to control the places that migrants can relocate to, thus keeping the biggest cities from being overwhelmed by new residents. A major benefit for migrants is that they now have better access to housing, schools, and health care.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

The migration of people from rural China to cities includes 160 million workers who have moved without legal papers and who now constitute half of China’s urban labor force.

Most rural workers who have moved to China’s cities without official permission are in low-

paying jobs with little or no access to social services or education. The current reforms to the hukou system are designed to better control the places that migrants can relocate to, thus keeping the biggest cities from being overwhelmed by new residents.

What Makes East Asia a Region?

Part of the region of East Asia is China, home to nearly one-

Terms in This Chapter

East Asian place-

Pinyin (a spelling system based on Chinese sounds) versions of Chinese place-

The region historically known as Manchuria is here referred to as China’s Far Northeast to emphasize its geographical location. Although China refers to Tibet as Xizang, people around the world who support the idea of Tibetan self-