9.3 ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 1

Environment: East Asia’s most serious environmental problems result from its high population density combined with its rapid urbanization and environmentally unsustainable economic development. Climate change may intensify the droughts and floods that have long plagued this region.

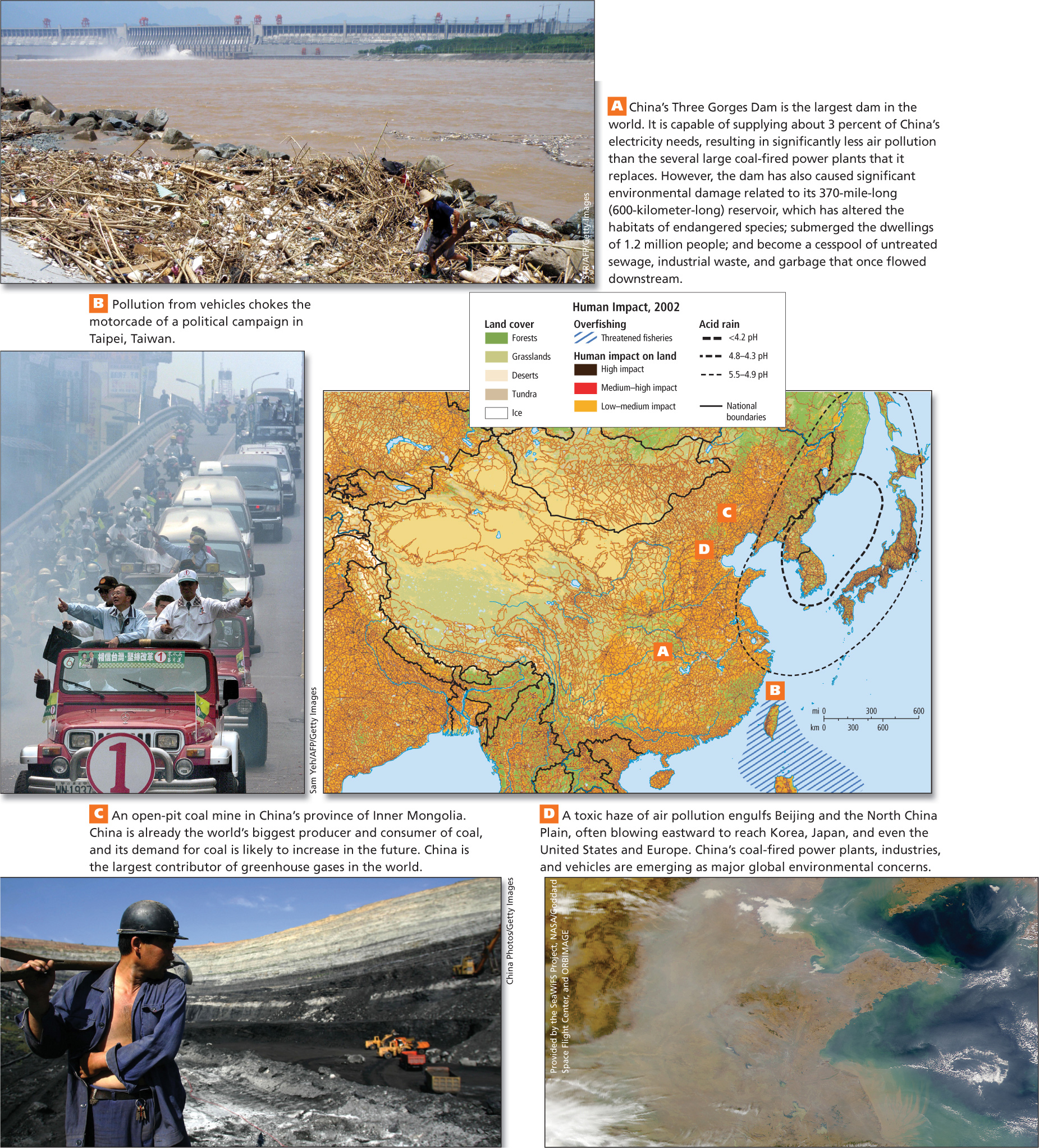

Climate change, especially global warming, is a growing concern in East Asia. China is the world’s largest overall producer of greenhouse gases (but still produces less than a third of U.S. emissions on a per capita basis; see Chapter 1). China has recently been working to limit its emissions for a variety of reasons, but even though it has significantly increased its efficiency through the use of new technologies, its emissions still make up almost a quarter of the world’s total. This amount may double by 2030 as China’s urban households use more cars, air conditioning, appliances, and computers. Japan, Korea, and Taiwan are also major greenhouse gas emitters.

China’s Vulnerability to Glacial Melting Glaciers on the Plateau of Tibet capture monsoon moisture and store it as frozen ice, which is then slowly released as meltwater. Two of China’s largest rivers, the Huang He and the Chang Jiang, are partially fed by these glaciers, which are now melting so rapidly that scientists predict they will eventually disappear. One effect could be significantly lower flows in these two great rivers during the winter, when little rain falls. Both have already begun to run low during winter, and trade has been affected because riverboats and barges have become stranded on sandbars. Another effect could be a reduction in the amount of irrigation water available for dry-

Water Shortages Nearly every year, abnormally low rainfall or abnormally high temperatures create a drought somewhere in China. These droughts often cause more suffering and damage than any other natural hazard.

Droughts can be worsened by human activity on a local or regional scale. When people begin to live or farm in dry environments, as many millions have done in China and Mongolia during the twentieth century, desertification (see Chapter 6) can result. People clear vegetation to grow crops, which require more water than the natural vegetation, so the crops must be irrigated with water pumped to the surface from underground aquifers (Figure 9.5A). Many dry areas in China are subject to strong winds that can blow away topsoil once the vegetation is removed. Furthermore, irrigated crops are often less able than natural vegetation to hold the soil. This has resulted in huge dust storms much like those that plagued the central United States in the 1930s Dust Bowl (see Chapter 2). High dunes of dirt and sand have appeared almost overnight in some parts of China that border the desert, threatening crops, roads, and homes. Dust storms can also move over long distances from western China and affect large cities, such as Beijing, near the coast. Particulate matter from these dust storms even circles the entire globe in the upper atmosphere.

VIGNETTE

In Ningxia Huizu Autonomous Region on the Loess Plateau in northwest China, Wang Youde squints out at what are now sand-

The Loess Plateau was already prone to dust storms during times of drought (loess means “wind-

368

369

Water shortages are particularly intense in the North China Plain, which produces half of China’s wheat and a third of its corn. Here the water table is falling more than 10 feet per year because of the increased use of groundwater for irrigation and urban needs. Meanwhile, withdrawals of water from the Huang He often make the river’s lower sections run completely dry during the winter and spring. A gigantic development called the South–

China is also trying to avoid water shortages, focusing on water conservation to stretch existing supplies. Already, 30 percent of China’s urban water is recycled, and many cities are trying to raise this percentage. China is also making a major effort to remove pollutants from wastewater discharged by industry and farming, which together account for 85 percent of water use.

Japan, the Koreas, and Taiwan have monsoon rainfall patterns, which give them a generally wetter climate and make them less vulnerable to drought than China and Mongolia.

Flooding in Central China The same shifting patterns of rainfall that may worsen droughts can also worsen flooding. Under usual conditions, the huge amounts of rain deposited on eastern China during the summer monsoon periodically can cause catastrophic floods along the major rivers. If global warming leads to even slight changes in rainfall patterns, flooding could be much more severe (see Figure 9.5C). Engineers have constructed elaborate systems of dikes, dams, reservoirs, and artificial lakes to help control flooding. However, these systems failed in 1998, when heavy rains in the Chang Jiang basin caused some of the worst flooding in decades, resulting in the death of approximately 4000 people. The pattern is now repeating frequently on the Chiang Jiang and other rivers in central and southern China (significant floods happened in 2010, 2011, and 2012). Every year there are large numbers of casualties from drowning and mudslides.

Natural Hazards and Energy Vulnerability Until the Sendai earthquake and tsunami of 2011, Japan, along with many other countries, planned to increase its use of nuclear power as a way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, the tsunami washed over the Fukushima nuclear plant and destroyed its cooling systems, which caused a meltdown of several of the plant’s nuclear reactors. The severity of the nuclear disaster that followed in the wake of the tsunami halted or curtailed many plans for expanding nuclear power in Japan and across the world. The accident forced the evacuation of more than 200,000 people and temporarily contaminated the water supply of Tokyo. For miles around the reactor, the ground, food, and livestock were contaminated and thousands of gallons of water, containing 10,000 times the normal level of iodine-

Food Security and Sustainability

East Asia’s food security—the capacity of the people in a geographic area to consistently provide themselves with adequate food—

food security when people consistently have access to sufficient amounts of food to maintain a healthy life

About 75 percent of the food consumed in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan is imported. In China, on the other hand, self-

Recent dramatic increases in global food prices illustrate the perils of dependence on food imports, especially for the poor. In 2007– 217. FOOD PRICES SKYROCKETING IN CHINA

217. FOOD PRICES SKYROCKETING IN CHINA

Food Production Just over half of East Asia’s vast territory can support agriculture (Figure 9.6). In much of this area, food production has been pushed well beyond what can be sustained over the long term. As a result, East Asia’s fertile zones are shrinking. In China, roughly one-

370

As urban populations become more affluent, they consume more meat and other animal products that require more land and resources than the plant-

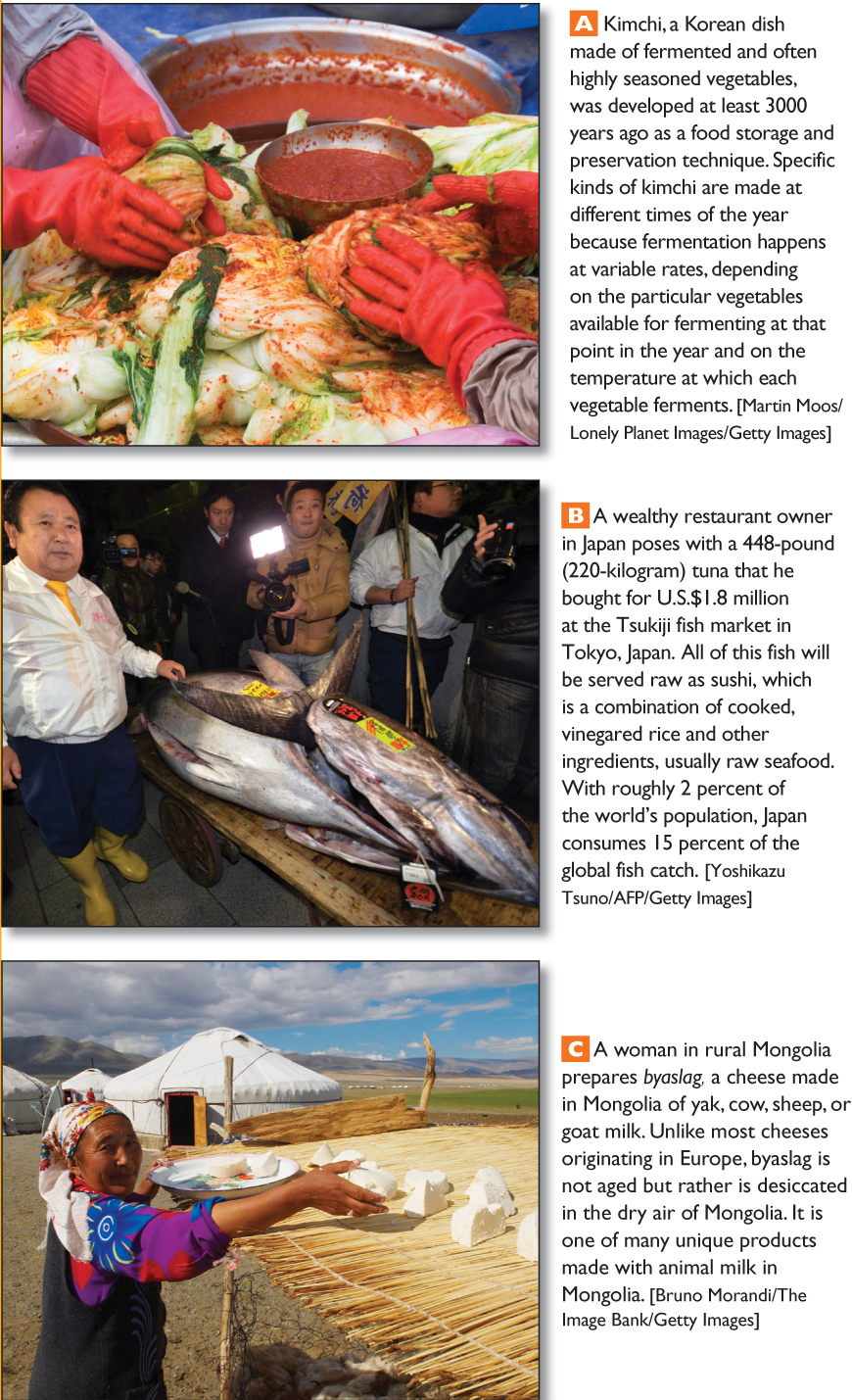

Even with the increase in meat consumption, vegetable dishes with an ancient history remain popular throughout East Asia (Figure 9.7A), and meat and dairy dishes are still prepared in traditional ways in places where raising farm animals has been the norm (see Figure 9.7C).

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Responses to the Climate Crisis

East Asia is increasingly responding to the warming aspect of global climate change. Japan has led these efforts for decades. In 1997, the Japanese city of Kyoto hosted the meeting in which countries first committed to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Japanese automakers such as Toyota were among the first to develop and sell hybrid gas-

Rice Cultivation The region’s most important grain is rice, and over the millennia its cultivation has transformed landscapes throughout central and southern China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. In these areas, rainfall is sufficient to sustain wet rice cultivation, which can be highly productive.

wet rice cultivation a prolific type of rice production that requires the plant roots to be submerged in water for part of the growing season

Wet rice cultivation requires elaborate systems of water management, as the roots of the plants must be submerged in water early in the growing season. Centuries of painstaking human effort have channeled rivers into intricate irrigation systems, and whole mountainsides have been transformed into descending terraces that evenly distribute the water. Writing about wet rice cultivation in Sichuan Province, geographer Chiao-

371

Fisheries and Globalization Many East Asians depend heavily on ocean-

There are also many large Japanese fishing vessels, complete with onboard canneries and freezers, that harvest oceans around the world. They can do so because waters at a certain distance away from land, typically 200 nautical miles (230 miles or 370 kilometers), are considered international waters and outside the jurisdiction of any individual country. Environmentalists have criticized Japan for overfishing. For example, Japanese fishing off western Africa has reduced the catches of local fishers so much that many have been forced to migrate to Europe for work. Today there is little room for Japan to expand its fish imports because the global wild fish catch has been static or in decline since 1990 because of overfishing.

China is today both the largest producer and consumer of fish in the world. Unlike Japan, the world’s second-

People and Animals Animals are used in East Asia not only for food, but also for medicinal, aesthetic, and cultural purposes. For example, traditional Chinese medicine involves, among other things, the capturing of wild animals. Such animals are found in markets around China because they are believed to have healing properties (Figure 9.8A). Unfortunately, due to this practice, some species are now endangered.

Particularly in Japan, aquaculture provides living ornamentation to gardens and other carefully tended landscapes. Carp have been domesticated and bred to have a variety of colors and patterns (see Figure 9.8C) and are a central part of many Japanese gardens. As an adaptive species that does well under a wide variety of aquatic conditions, ornamental carp are now found around the world.

Animals are often central to a culture, as is the case in Mongolia, where many species of animals are fundamental to the nomadic culture that historically dominated there. A way of life once common in areas of dry grasslands around the world (see Figure 9.8B), nomadic living is becoming less common than it was in the past as places like Mongolia become more urbanized.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 1

Environment East Asia’s most serious environmental problems result from its high population density combined with its rapid urbanization and environmentally unsustainable economic development. Climate change may intensify the droughts and floods that have long plagued this region.

China’s main river systems are being affected by the melting of its glaciers, which ultimately leads to water shortages.

The region’s most important grain is rice, and over the millennia, rice cultivation has transformed landscapes throughout central and southern China, and Japan, the Koreas, and Taiwan.

372

About three-

quarters of the food consumed in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan is imported. So far, China is self- sufficient with regard to basic necessities such as rice, but it is highly dependent on imports for other foods. People in East Asia consume much fish and seafood. Some of this food is harvested in waters far away from East Asia.

Three Gorges Dam: The Power of Water

The Three Gorges Dam (Figure 9.9A) is at this time the largest dam in the world, at 600 feet (183 meters) high and 1.4 miles (2.3 kilometers) wide. It was designed to improve navigation on the Chang Jiang and control flooding, but it is most lauded for its role in generating hydroelectricity for China, a country that uses considerable amounts of energy and is working to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. But the dam also comes with a social cost. The Chinese environmental activist Dai Qing notes that China has 22,000 large dams, all of which have displaced people—

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 9.4

axluPlY4lalrxeQNSQpukfqGntA1jqkC88UZN4HR08L/4vzuKf5QsifVZYrt3Q8exAWIat0gMnmrXAYAzsWEFX9cJh2cAgr1zuC9ooN1od6FIHGvgKevwzh3zeVJTwXOuW+N5+jRb8xZOdpKrJRuxnWp/7k=Question 9.5

LE6rYTxGFOUrR+zJhM3e/Et670dnP7bcA3+uoJ9N4tlyRSe4JirlYiyEUM4aGsShWFLWol/kV5atOI7x9zWingjRdoM=Question 9.6

mnb3jujjDGSoTlQOjKtVVxMlDvNEyOOTWnP6aOtRA8Lez3QvLafxe0cgbR6UaD2psOzd8wpxBFQK6Vps7PQ8aU7KnN5CiaLw7rb1VwwAYJ8sajP9ehuV0AJEuXf8N7NBibPrJg==Question 9.7

vHawbikapHDMB+a2CV7XPXSouJz17G7F0t05tA1DP5jObsGX3tLDvFH0A5ClBz2Qv3Gy1VrvxRAb+NgPTeQRu3QJsjVUVATQJdddhm0vq5/dh2pMoLcAW4Z007FJfnSllUzV4MW5sA0=Many experts involved with the Three Gorges project see serious design flaws. Of greatest concern is the dam’s position above a seismic fault. The dam was built at the east end of the Three Gorges because the deep canyons provided a prodigious reservoir for water to power turbines, providing electricity for all of central China, from the sea to the Plateau of Tibet. Unfortunately, the enormous weight of the water and its percolation through geological fissures in the 370-

Any failure of the dam would be a financial as well as human disaster. Official construction costs are $25 billion, but the real costs may end up being three times this figure, due in part to unforeseen negative environmental and social impacts and to theft from the project by corrupt officials.

Also of concern is the incalculable cost associated with relocating the 1.2 million people who once lived where the dam now forms a reservoir. Thirteen major cities have been submerged, along with 140 large towns, hundreds of small villages, 1600 factories, and 62,000 acres (25,000 hectares) of farmland. In some cases, communities were rebuilt immediately uphill from the submerged location and people only had to relocate a short distance; others had to migrate to distant parts of the country. The reservoir has also destroyed important archaeological sites, as well as some of China’s most spectacular natural scenery. There are significant environmental costs as well. The giant sturgeon, for example, a fish that can weigh as much as three- 209. THREE GORGES DAM LEAVES SOME CHINESE SWAMPED

209. THREE GORGES DAM LEAVES SOME CHINESE SWAMPED

The plan to build the Three Gorges Dam came just as UN development specialists were deciding that the benefits dams could bring do not sufficiently outweigh the many problems they cause. Decades ago, international funding sources such as the World Bank withdrew their support for the Three Gorges Dam because of concerns over the social and environmental costs and other shortcomings of the project. However, Chinese industrialists who need the energy, construction companies that have prospered from building the dam and its many ancillary projects, and government officials eager to impress the world and leave their mark on China continue not only to support the Da Ba (the Big Dam), but also to look for other locations around the world where China can gain influence and profit by building dams.

373

374

Air Pollution: Choking on Success

Air pollution is often severe throughout East Asia, but the air quality in cities is particularly poor. After South Asia, the pollution in East Asian cities ranks among the worst in the world. China’s pollution problems are particularly important because its demand for energy is growing so fast. Globally, coal burning is a major source of air pollution, and China is the world’s largest consumer and producer of coal, accounting for 46 percent of all the coal burned in the world each year (see Figure 9.9C, D). Between 1980 and 2011, China’s coal consumption grew sixfold. By 2006, China was bringing a new coal-

The combustion of coal releases high levels of pollutants—

VIGNETTE

Every winter, an elderly couple got through the biting Beijing winters by feeding 1200 one-

Sulfur dioxide from coal burning also contributes to acid rain, which is displaced to the northeast by prevailing winds that reach the Koreas, Japan, Taiwan, and beyond. Figure 9.9D and the map above it show the zones of heavy pollution. Japan and Taiwan are particularly afflicted (see Figure 9.9B). Particulates from China’s coal burning are transported globally by high-

Air pollution from vehicles is also severe even though the use of cars for personal transportation in China is in its early stages. For years, China’s vehicles have had very high rates of lead and carbon dioxide emissions. The government has begun to work on the problem. As of 2008, new Chinese cars had to meet EU standards for mileage and emissions— 203. WORLDWATCH INSTITUTE: 16 OF 20 OF WORLD’S MOST POLLUTED CITIES IN CHINA

203. WORLDWATCH INSTITUTE: 16 OF 20 OF WORLD’S MOST POLLUTED CITIES IN CHINA

375

Air Pollution Elsewhere in East Asia Public health risks related to air pollution are also serious in the largest cities of Japan (Tokyo and Osaka), Taiwan (Taipei), Mongolia (Ulan Bator), and South Korea (Seoul), and in adjacent industrial zones. Even with antipollution legislation and increased enforcement, high population densities and rising expectations about better living standards make it difficult to improve environmental quality. Taiwan is a case in point.

Taiwan has some of the dirtiest air in the world. Some of the main causes are the island’s extreme population density of 250 people per square mile (646 per square kilometer), its high rate of industrialization, and its close proximity to industrialized south China. There are now 4 motor vehicles (cars or motorcycles) in Taiwan for every five residents—

Both North and South Korea depend on hydro-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

In an effort to address droughts, floods, and its burgeoning need for electricity, China has built many dams, the largest of which is the Three Gorges Dam, which now poses many potential problems itself.

Rapid urban economic development in East Asia, combined with weak environmental protection, has resulted in some of the most polluted cities on the planet.