9.6 POWER AND POLITICS

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

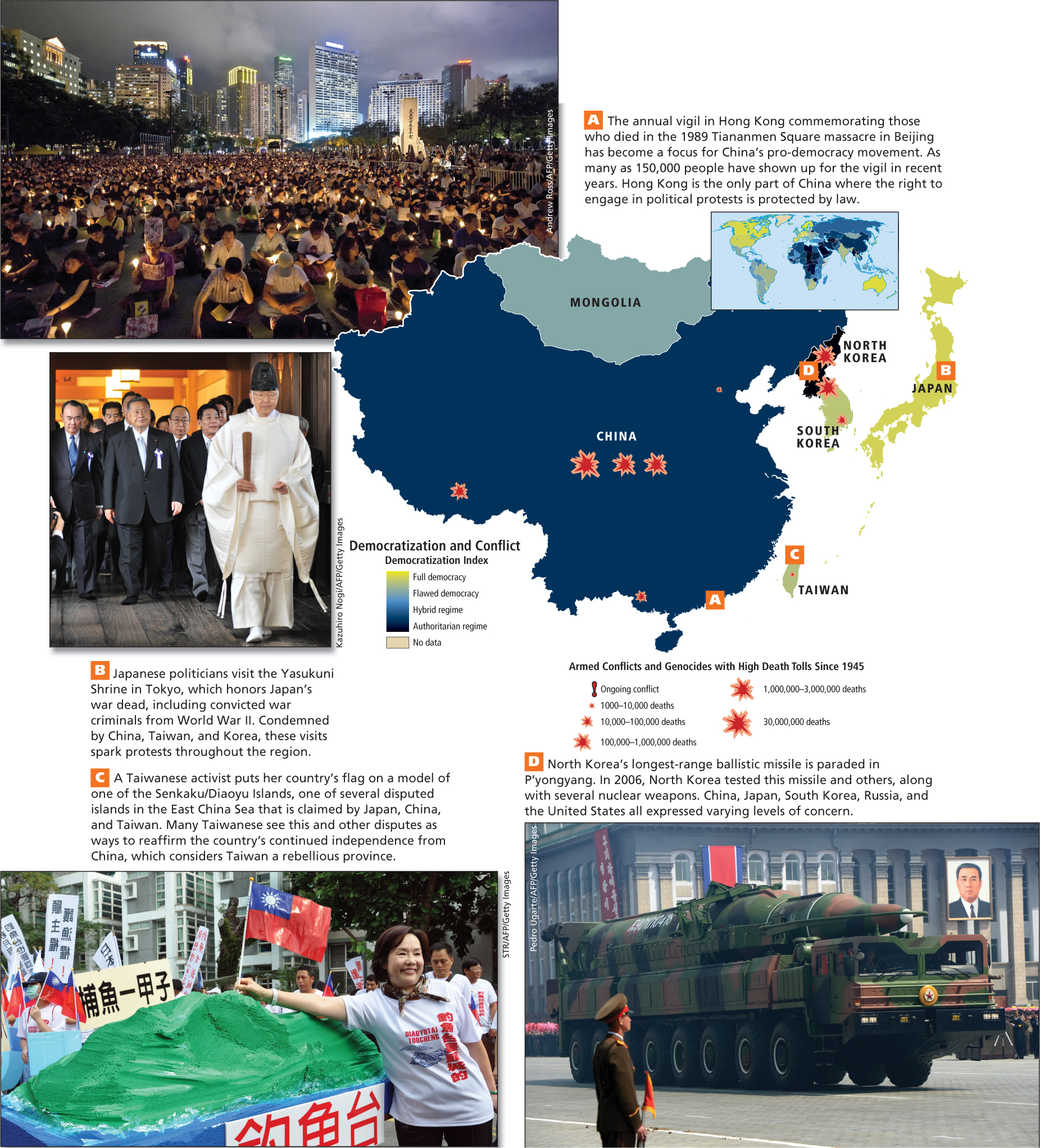

Power and Politics: As East Asia has developed economically, the pressure for more political freedoms has grown. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are now among the more politically free places in the world, and demands for political change in China are increasing, especially in urban areas.

Demands for more political freedom are growing throughout East Asia. Japan’s current political structure was established after World War II, South Korea’s in the late 1980s, and Taiwan’s in the mid-

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 9.14

WeFOBiD8wYP0sI0y/kDGqbzzl1GCD97Uw4PNp6kzseJRiuQP1SC4Ii5KiK6xwd/HpEsbu/JhxSq/OzbT3KKVJY+UPAE=Question 9.15

VbUsJ8hSG1dgre3LBa58ZrrGNKoo20K3YaPVm9bwADQ0HZsj9JURx/XRXXz0jBK63Iyobxhr7VIRTW/SM2IMCA==Question 9.16

A/BdJ9sC3Tf7xV0QiWHCpCJhdg9OjEr8cUkXJKp4xpxy72GXfzbxlwFf7fYJX2y1RCjM2VI5GCBPglmNxLZI4MG1TmMUDac03nVjMAWWVdRviO825KI88rLORnHD3RjV+bp45hK9OJ0XNXDQL9+l7GxJiq418x8a385

Pressures for Political Change in China

With China now a globalized economy, many wonder how much longer the Communist Party can remain in control without allowing a significant expansion of political freedom throughout the entire country. The Communist Party officially says that China is a democracy, and indeed some elections have long been held at the village level and within the Communist Party. However, representatives of the National People’s Congress, the country’s highest legislative body, are appointed by the Communist Party elite, who maintain tight control throughout all levels of government. Most experts on China agree that while radical change is unlikely in the near future, a slow but steady shift toward more political freedom is underway. Change might be inevitable as the population becomes more prosperous, educated, and widely traveled, thereby becoming exposed to places that have more political freedoms. However, the Communist Party remains determined to repress any major reform movements that arise from outside the party’s senior leadership.

386

Less than a decade after market reforms began, demands for political change culminated in a series of pro-

International Pressures Informed consumers and environmentalists in developed countries have criticized China for its “no holds barred” pursuit of economic growth. Much of China’s growth has been built on environmentally destructive activities and harsh conditions for workers, both of which effectively reduce production costs so that the prices of Chinese goods are low on world markets.

The 2008 Olympics in Beijing highlighted a number of issues that have also created an impetus for increasing democracy. Before the games, the international media drew attention to the human rights abuses of workers, protesters, prisoners, ethnic minorities such as Tibetans and Uygurs, and spiritual groups. The most prominent of such groups is Falun Gong, a Buddhist-

211. OLYMPIC RELAY CUT SHORT BY PARIS PROTESTS

211. OLYMPIC RELAY CUT SHORT BY PARIS PROTESTS

213. BEIJING OLYMPICS: POLITICAL BATTLEGROUND?

213. BEIJING OLYMPICS: POLITICAL BATTLEGROUND?

221. REPORTS OF SALE OF EXECUTED FALUN GONG PRISONERS’ ORGANS IN CHINA CALLED “SHOCKING”

221. REPORTS OF SALE OF EXECUTED FALUN GONG PRISONERS’ ORGANS IN CHINA CALLED “SHOCKING”

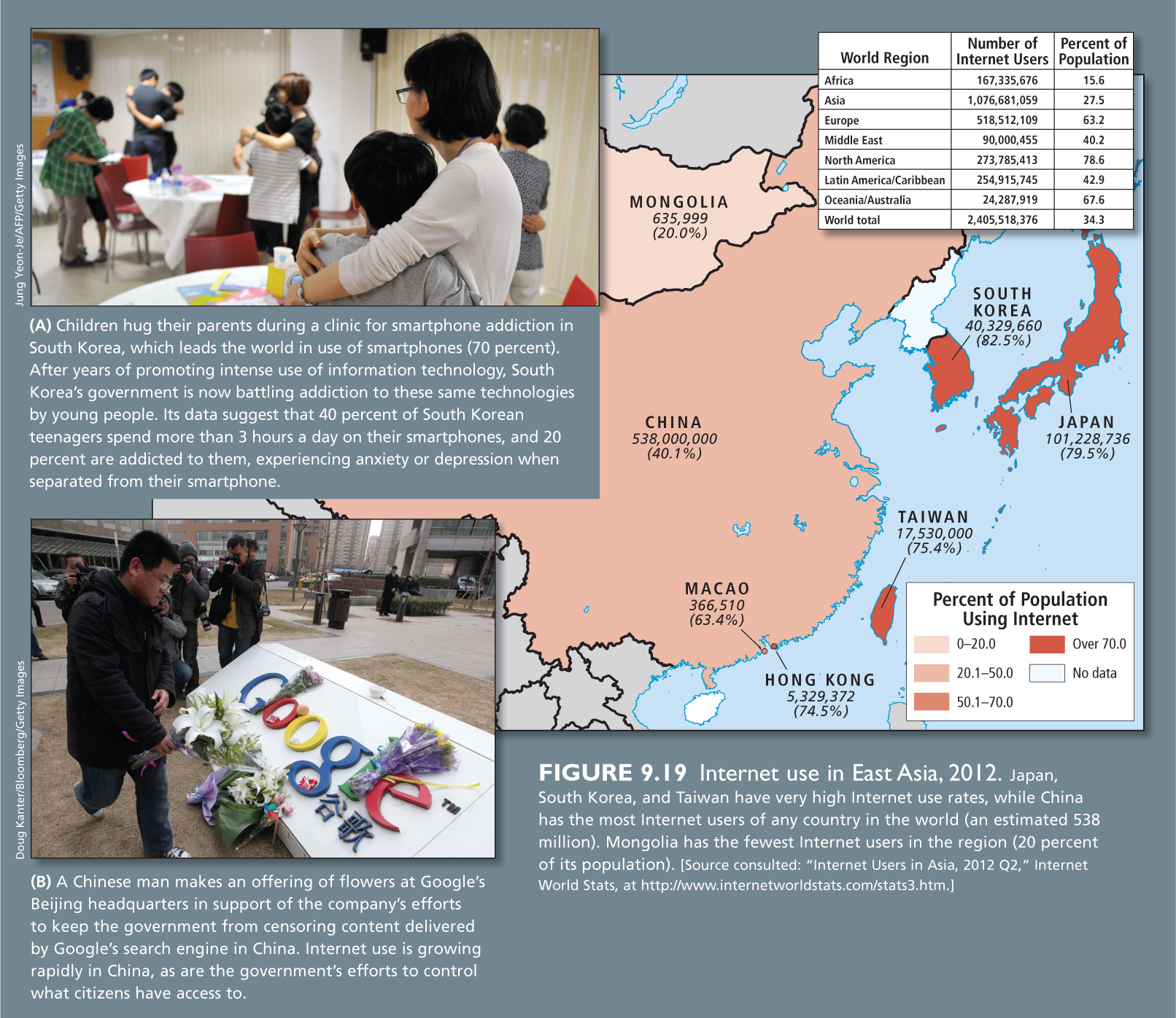

Information Technology and Political Freedom The spread of information via the Internet has increased the push for political freedom from within China. Since the revolution in 1949, China’s central government has controlled the news media in the country. By the late 1990s, though, the expanding use of electronic communication devices was loosening central control over information. By 2001, twenty-

387

388

Not too long ago, telephones were very rare and people had to obtain permission to use them, but now millions of Chinese people have access to an international network of information. It is much more difficult for the government to give inaccurate explanations for problems caused by inefficiency and corruption. Journalists can now check the accuracy of government explanations by phoning witnesses or the principal actors directly and then posting their findings on the Internet. Analysts, both inside and outside China, see the availability of the Internet to ordinary Chinese citizens as a watershed event that supports the expansion of political freedom.

Social networking technologies have emerged as a powerful tool for collective action in China. In recent years, the use of cell phone–

389

Nevertheless, the Internet in China is not the open forum that it is in most Western countries. Since 2013, Chinese Internet users have been required to register their real names when using an online account. This is an attempt by the government to monitor free speech and anonymous criticisms against party officials. And if people writing blogs in China use the words “democracy,” “freedom,” or “human rights,” they may receive the following reminder: “The title must not contain prohibited language, such as profanity. Please type a different title.” Such censorship, informally dubbed the “Great Firewall,” has been aided by U.S. technology firms such as Yahoo and Microsoft, which allow the Chinese government to use software that blocks access to certain Web sites for users in China. Google, in dispute with the Chinese government over state-

Protests and Political Freedom Protests by workers for better pay and living conditions, and by farmers and urban dwellers displaced by new real estate developments are becoming increasingly common. China’s government reported that there were 58,000 public protests in the country in 2003. This number rose to 74,000 in 2004 and 87,000 in 2005. Since then, the government has stopped issuing complete statistics on protests. The nonprofit group Human Rights Watch estimates that 100,000 to 200,000 such protests are being held each year.

Many people have joined interest groups that pressure the government to take action on particular problems. One of the most publicized of such groups was formed by parents whose children died after schools collapsed during a massive earthquake (which registered 7.8 on the Richter scale) in Sichuan in May 2008. They demanded changes in policies that allowed schools to be poorly constructed and pushed for compensation for their lost children.

In December 2008, people seeking more political freedoms signed a manifesto called the 08 Charter, which calls for a decentralized federal system of government (that is, more power to the provinces), democratic elections, and the end of the Communist Party’s political monopoly. Liu Xiaobo, coauthor of the 08 Charter, was arrested, and in December 2009 he was sentenced to 11 years in prison, even as prominent international human rights activists lobbied on his behalf. In 2010, Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, though neither he nor his family was allowed to attend the ceremony in Norway.

In an effort to maintain control over China’s increasingly articulate protestors, the government has allowed elections to be held for “urban residents’ committees.” The idea seems to be to provide a peaceful outlet for voicing frustrations and creating limited change at the local level. Many of these elections are hardly democratic, with candidates selected by the Communist Party. However, in cities where unemployment is high and where protests have been particularly intense, elections tend to be more free, open, and truly democratic. It could be that interest group protests are an important first step toward actual participatory democracy, even when some, such as those who signed the 08 Charter, are harshly stifled.

Japan’s Recent Political Shifts

Significantly, the government that played such a central role during the post–

Political Tensions Between East Asian Countries

In recent years, political tensions have been rising between the countries of East Asia even as their economies have become more linked. While these tensions are rooted in contemporary economic conditions and political calculations by governments, they are also fueled by the painful legacies of World War II and its aftermath.

Recently, two major disputes between East Asian countries have arisen over uninhabited islands that lie over oil and natural gas reserves. In the case of the Spratly Islands of the South China Sea (see Chapter 10), both China and Taiwan are pursuing claims to the islands, as are several Southeast Asian countries.

In the East China Sea, the Senkaku Islands (in China, these are known as the Diaoyu Islands) are claimed by China, Japan, Taiwan, and Korea. The conflict over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands has escalated lately, mainly because of competing claims on them by China and Japan. Because China and Japan are the world’s first-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Power and Politics As East Asia has developed economically, the pressure for more political freedoms has grown. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are now among the more politically free places in the world, and demands for political change in China are increasing, especially in urban areas.

390

By 2012, there were 538 million people in China using the Internet, representing 40 percent of the country’s population. China has strict controls on Internet access and use, but social networking is being used to promote the expansion of political freedoms.

Chinese citizens who share a grievance against the government are increasingly cooperating with one another in their protests. In December 2008, a manifesto for change, the 08 Charter, was signed and submitted to the government by 350 protestors.

In Japan, one political party has controlled the government for all but 3 years since 1955, leading to criticism that Japan lacks a vigorous democracy.

Recently, two major disputes between East Asian countries have arisen over islands that may lie over oil and natural gas reserves.