Chapter 7. A Day at the Beach

Introduction Part 1

A Day at the Beach

By Justin Hines, Lafayette College and Marcy Osgood, University of New Mexico

Popup content goes in this box

Instructor's Notes

Topic Pre-requisites: Students should have exposure to the topics of Chapters 14-21 and 24-27 of Tymoczko Biochemistry: A Short Course, 3rd ed.

Overview

This case is designed to help students understand the importance of fatty acid transport into mitochondria, the role of carnitine in this process, and the interconnections between carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in humans. The case also explores the roles of the hormones insulin and glucagon in regulating energy metabolism in humans. As such, we have anticipated that students will have been exposed to material in the textbook through Chapter 27 of Tymoczko Biochemistry: A Short Course, 3rd ed. before beginning the case (coverage of chapters 22 & 23 are not necessary). Students may work individually or in groups to complete this case study. Students are constantly encouraged to refer to their textbook throughout the case, and internet access is permitted, although it is not necessary for the completion of the case. Students are required to iteratively acquire, analyze, and integrate data as they progress through the case and answer assessment questions found throughout the case. All assessment questions are automatically scored.

The case will also keep track of the number of investigations that students conduct and report this number to the instructor; students are made aware of this fact as a means to encourage careful consideration of investigation options and discourage guessing. It is entirely up to the instructor what to do with this information; we suggest potentially rewarding students who efficiently solve the case and/or penalizing students who obviously relied on blanket guessing (evident by the use of all or nearly all investigative options). For reference: there are 32 total investigative options within the case and 13 are minimally required to complete the case. We anticipate that careful students will typically make use of 15-20 options in solving this case.

Learning Objectives

This case is intended for remediating or extending student capabilities in these difficult topics:

1) The real-world application of the study of human metabolism. Students will:

- Utilize real biochemical tests to evaluate and ‘solve’ a metabolic disorder case

- Consider the importance of factors like personal and family history, diet, medications taken, and symptoms in solving a biochemical case

2) Connections between carbohydrate and fat metabolism in humans. Students should be able to:

- Outline and explain the importance of carnitine-mediated fatty acid transport into mitochondria

- Review fatty acid metabolism pathways and regulation

- Explain the importance of ketone body formation in human metabolism

3) Practice critical thinking skills involving data. Students will:

- Evaluate data provided by metabolite and enzyme tests

- Integrate multiple pieces of biochemical data

Some questions are designed to address areas of difficulty for students

- Students often struggle with predicting the changes in flux through various metabolic pathways as a result of different nutritional states (and resultant hormone levels). This is particularly challenging when multiple tissues are considered. This issue is addressed in numerous assessment questions throughout the case.

- Students often harbor misconceptions about ketone body formation, specifically about its purpose and cause(s). This issue is addressed in multiple assessment questions throughout the case.

- Author note: A common error is to jump immediately into testing a ‘pet’ hypothesis by conducting laboratory tests (metabolite assays or enzyme assays) before exploring ‘data gathering’ options like visual inspections, or simply interviewing the person. This is an excellent and intentionally designed opportunity to point out a common mistake about the scientific method--that is, it begins with making careful observations, rather than by immediately testing quickly formed hypotheses.

Suggested implementation

Below we describe two options for course implementation. The hybrid Online/In-class approach is recommended. Time required for students to complete the online case will vary by group depending on their level of discussion between each investigation. The case study can be started and stopped, and so it is recommended to give students a window of 3 to 5 days in which to complete the assignment.

Hybrid: Online/In-class: (recommended approach; ~30 minutes of class-time expected)

- Share the case study link with your students to work online outside of class, preferably in pairs or groups of three. Assign the case study to be due before your next class meeting. Students should be instructed to bring copies of notes and answers to assessment questions to the following class period.

- Review the online answers before the following class for difficult areas for students (see expected areas of difficulty above).

- Lead students in a discussion in pairs, groups, or as a class (depending upon class size and instructor preference) to address unresolved difficulties (~30 minutes in-class time).

- We recommend using the supplied assessment questions on exams or as homework assignments to reinforce the difficult concepts covered. Please see the document “Exam Questions Case 3- Lipid Metabolism”

Online only approach: (minimal in-class time required)

- Share the case study link with your students to work online, preferably in pairs or groups of three. Assign the case study to be due before your next class meeting.

- Review the online answers for difficult areas for students (see expected areas of difficulty above).

- Mention or remediate tough points during a portion of lecture.

- After using the case, we recommend that you select questions from the supplied assessment questions to use on exams or as homework assignments to reinforce the difficult concepts covered. Please see the document “Exam Questions for Case 4: Integration of Metabolism.”

Suggestions for in-class discussions (these questions may also be used in summative assessments-- i.e., exams, scored quizzes, etc.):

- What were some of the most important facts of Jessie’s case that were revealed as a result of your investigations and why were they important?

- Students could be directed to brainstorm in groups or as a whole class.

- Does Jessie suffer from an inborn error of metabolism? Explain your answers. How was she able to be a successful athlete in her past?

- This question could be easily used as a think-pair-share exercise.

- Alternatively, this question could first be answered in writing by individual students and then those responses collected or discussed in groups and revised.

- What was the relevance of Jessie’s diet in this case?

- Why did Jessie’s liver show increased fat deposition?

- Why was Jessie unable to make ketone bodies during a fasting study and why was she suddenly able to create ketone bodies when given short-chain fatty acids?

- This question could be easily used as a think-pair-share exercise.

- Why did Jessie have abnormally low blood glucose during a fasting study?

- Students could be directed to brainstorm in groups or as a whole class.

You are missing vital information

You may be missing vital information needed to sufficiently explain this incident. You must complete all investigations before proceeding to the final assessment questions.

You are missing vital information

You may be missing vital information needed to sufficiently explain this incident. You must complete all investigations before proceeding to the final assessment questions.

This activity has already been completed, however feel free to review the information contained within.

I am finished gathering information for this investigation and feel I am able to fully explain the reason(s) for Jesse’s incident in biochemical and physiological terms, and I can fully justify and completely explain my reasoning based on the evidence I have gathered.

Jessie knew she was late for the family reunion, probably too late for the big picnic lunch at Forest Lake Beach, but too early for the barbecue dinner. “Too bad” she thought, because she had skipped breakfast as well, trying to get out of the city and on the road to the lake. Perhaps there would be some leftovers; she hoped so, because she was beginning to get that slightly dizzy feeling that meant she was pushing her limits.

No leftovers, but the whole extended family was there: sitting and talking on the beach, playing Frisbee golf, and throwing a football. Some of the younger cousins were having swimming contests out to the floating platform at the edge of the swimming area. Jessie watched the kids swimming, and smiled sadly. She had been a competitive swimmer as a teenager and still missed it. As she watched the group of splashing children, Jessie began to think that something wasn’t right about a little boy off to the right of all the others. She put her hand up to shade her eyes from the sun and squinted; the kid was in trouble! He was throwing his arms around randomly, and thrashing the water into froth. None of the other children were close enough to notice, and there didn’t seem to be any other adults near enough to raise the alarm.

7.1 Introduction Part 2

Without any further thought, Jessie ran into the lake, and after the first few lunges through the water, dove shallowly and began swimming towards the now sinking child. Her muscle memory kicked in and her strokes became fast, efficient, and powerful. With each stroke she raised her head enough to keep the small head in sight; she was making progress, but he was going down! She pushed harder, picked up speed, and then she saw him, underwater, sinking quickly despite his frenzied paddling. Jessie took a breath and dove; she grabbed the little guy’s surfer swim shorts, and kicked hard back toward the surface. She began the one-sided stroke that allowed her to keep his head above the water, and swam toward the beach, which seemed, strangely, to be disappearing into a haze. Jessie felt exhausted, but kept swimming, breathing in short gasps. Her vision narrowed, and she barely felt the sand under her knees as she reached the shallow water. As the little boy was taken from her arms, Jessie lost consciousness.

7.2 Introduction Part 3

Jessie woke up in the hospital emergency room, very weak and confused. She tried to sit up, but her arms and legs felt heavy, completely without strength. She was dizzy, disoriented, and exhausted. A gray-haired woman in a short white coat came into view, as well as a younger person dressed in scrubs.

“Hello, Jessie. Glad to see you’re finally awake. You were out for a pretty long time. I understand you are a hero; saved the day and your little cousin. Can you tell me what happened to make you faint? Did you hit your head, or swallow too much water? Everyone said that you were a really good swimmer, and so no one understood why you fainted.”

Jessie took a deep and unsteady breath. “I haven’t tried to swim that hard since I had a head injury, 5 years ago." When the ER doctor asked Jessie if anything like this had happened to her before, she looked sheepish and said “yes”. She recalled similar episodes, all under similar circumstances—"pushing herself too hard".

7.3 Gathering Information

You are a biochemistry student who is shadowing the ER doctor. With the assistance of the physician, you may conduct additional investigations to determine the cause of Jessie’s incident. The goal of this exercise is to correctly solve the biochemical case without carrying out completely unnecessary investigations; hence, you are encouraged to carefully consider the information you receive with each investigation and avoid haphazard guessing. You will be scored on this exercise based on your answers to assessment questions found throughout the case so you are STRONGLY encouraged to use your textbook to complete this exercise; you may also use the internet as necessary.

Please note that there is a minimum set of investigations that must be conducted in order to have all the necessary information to fully understand the case. The number of investigations you select will be recorded and reported to your instructor, so randomly guessing could adversely affect your score. You should be both thorough and thoughtful in conducting your investigation. Hint: we recommend that you first thoroughly exhaust the use of broader initial investigation options, like interviewing someone, before proceeding to test specific hypotheses by doing more specific tests for particular enzyme activities, for example. After completing these initial investigations, ask yourself, what further investigations or lab tests would you like to conduct based on the information gathered so far? For starters, you might also consider what, metabolically, might make a person lose consciousness…

7.4 Investigation Options

RECOMMENDED INITIAL INVESTIGATIONS

Evaluate overall physical appearance including the presence of insect bites or other injuries

Results: Subject is a young, adult female with a slim, athletic frame but otherwise appears normal.

Fecal analysis – Look for blood, intestinal parasites, high levels of fat in stool

Results: No blood or intestinal parasites were found. Levels of fat in the stool were normal considering the subject’s recent food intake.

Interview patient to determine dietary habits and look for neurological problems

Results: No abnormalities in cognitive function were found. Jessie reported being a strict vegan for many years; however, she claims to get a large amount of protein from plant sources. She also reports eating a high calorie diet and occasional, moderate alcohol consumption. She says that she is a non-smoker, does not use illegal drugs, and does not recall eating anything unusual recently; in fact, she had not eaten anything yet on the day of the fainting episode because she was in a rush. You ask whether she knows whether she might be diabetic or has had any trouble in the past controlling her blood sugar levels and she responds by saying “I really don’t know.”

Investigate past medical history

Results: Jessie explained that she was on the verge of gaining a swimming scholarship to college when she injured her head in a rock climbing accident. Her head injury led to epileptic episodes that were now controlled by regularly taking anticonvulsant drugs. Swimming was one of the activities she gave up because of the fear of seizures. She reports that, since the accident, she has had less endurance, which she had always ascribed to the fact that she was no longer working out regularly. She sighed and said longingly, “I don’t swim anymore… don’t really do much of anything in terms of hard exercise. I am just miserably out of shape, I guess.” You ask whether she has had a blood test to look at her blood lipid profile recently and she responds that she has not had a full physical since she was dismissed from the hospital five years ago.

SECONDARY INVESTIGATIONS

Determine Blood Serum Concentrations

Common electrolytes: Ca2+, K+, Na+, Cl-, PO43-

Results: All values are in normal ranges. (normal ranges: [Ca2+] = 8.5-10.5 gm/dL; [K+] = 3.5-5.0 meq/L; [Na+] = 135-145 meq/L; [Cl-] = 100-106 meq/L; total phosphorus = 2.6 – 4.5 mg/dL)

Common lipids: free fatty acids (FFAs), triacylglycerides (TAGs), total cholesterol, and ketone bodies (acetoacetate as a marker)

Results: [FFAs] = 500 mg/dL (normal range: 190-420 mg/dL); [TAGs] = 175mg/dL (normal range: 40-150 mg/dL); [Total cholesterol] = 140 mg/dL (normal range: 120-200 mg/dL); acetoacetate was undetectable

Question 7.1

+EksqVu9lki0znFZ7WisUvBGUwOu4RQNXpgn8tb15JAHgHg2oSHlnX0KNV6L88tGYnsIbZWVcYLUKh3uABQz0qIkzm6+ed13YyQGUjZCOQ19FtvhFqqF7mG+3mmbaoOIVr9R0TW7oSj8oB4WTvXlKyxm9oJ9LEU5y4KHOmUhi44o7QFDmJY9wj5vBsNIG90Y10Z5H/RhvLQ/MjH83mToR1DicWaEUDjZpYPghQXbqwhMnSMvt4duAxFDsEEEuPCQoEC3dUYPfyxynRobNmjnSJH9j6os/ur51bahp2AmqggsDSYUo3wJyc96Ts70M1k8cHNVYvTQOWaOyYeRKW9osQ2DE34u8TsruI61eeLmwj49HXPdTAK8Eiz5NYKgsZ6YoxuC9z8yYeL36865Cybap+6IcmzA17p3zR+61SDwKFdJXAM3EDsAT8GH3OGxrwZeXKWqVO55t0DwyyyaSBZ0C31+OnRnKWzqlgKfoheStv5obhCZEN2UiGiftWM0H7gjHVo9brZgJ2Gq3GHjVgcy7uNZWmp/f/2+7F7+FkNpUa5oD6d540GZ4SVt1+PvHvZYC2SEAGDVrJQYDBHUZEcHbAK26u5IqEIP3vav3W21mvptp8s45qjoZVNaFlZGnE87PhetrW2MbByedVJCqy8Ubcen/LMz1HmsjU+NrJG+2+Z7LOH+oY8zhqayYEo5Q249LN0EcAs/nbpbNa5HE7YvL3HMhk3SNClZsMqMQz0dG7vF3jlR2FQcV/R5n1eNaU8TlkMKk/fMp/vaN0JwD7MTS6vIiITxKC0+UkRNcxlJOl6+QDEC1TXxSLdpISmptk8hqgqhhL/BXfY4UZ7oGGnPYkoSBSVAJYNkOwhXUZLhVHzYGj7+Hm1xG5WyeBwHlwrLUPJPe32bJFb9/jshcdTqCgLHM2lZunjl8eHQGRv4nSNp6p4JMtrfggEd0Ub7ZVkTCESzR+xFa6s6O6zPF6gwig1DLe3W41Nv+ytHmiZB6gbBNoQvBzStlqqF4v6e6Pa3tliSJLaB65fFz0bTWNUScHTyHHo5DuayQ+ada6r4mTr/maB1IdWTTTCalDNGgYzyMDs/mmXPKjCUOz6lFRxm3QCjdFhqc5GC/Xtys0mdmxaDKQ3Ds2PcX+OyHvcGPEdWu0IwWtSR1DwAie+8r0E5qPVKtpGZzprUeXVgonWCHdDFI2lN2f6QNRMnfmcy14vfURyLu7afFV5ZLYzdpCGO3mgUac3yP97vu8sPGLD/f0Mg8sz+3DhsMHXNhO6AbdUWcNX6PebKwuNxSDWKY6qEWJSUfyqeHk2MbNuyteT7g9QXyCFXIBb4Sg42PviI+Wo2jgH7vI+/gQjgdl1KP7XrBMfpV+h2aIbOkS33DDZXWZHg3PQKSsgNQ6Myj5Lgarb2z3RloxXMN3uJkcp97rAjHjC6vjc4a5M3eInx5WyfgsLZo6aTknz3mkfmLCqzLuRFVNpgKWEHcKYLOD8KhtjeIykve3Qt8gyVB/PD0xxI+Lg01Nev2FaGQDkbTIFAVyDgWC8JjYgb5Y+FHQRamZzWlvh42VEr+Y5T9lNlSI0Xxowsa4w3h5Nfh5vYlYLGUclLUO0ce+ZDAT+rpIkSlPKtT2TQBhSuQan01B4l1SD2tVGvxH0Ys075yC3n9ix+DN8HiVWmmYXTky6/SlHchvMwhIMLMhKEky3N51KKHrK5/Ro=Question 7.2

VyV68LXC9amVy+h5acpBtnGovzlPqJLW82X7QJofQqTnXEI7iJUv7MM/GP+d5YaOp1KA7WnMpRu8hwz+ZpwXWQiErJjsFFaE/MyFI+It7rqYbQ2oBhemQvoZrzEpFM71IUAZZgDpjkgqxklnGA6Vdpz3BkYbDZJuwYk8Dtgv3X61wLmPRxdhaNAj4WOh453xFzrkSRI+TBkVnWXdjKbogOlOr3+51XIov9gR4yT1QYyNF/0p5qtHzvxUkrV5tF6Dh+gCcuD0PqDO0fI3tA2GxuJDLeOK5Wh81uqQpp3YS/KdnvpC8+Cdhu6mRv79XsQbAkvDsyHIcXTZsQY3SQEUX/iAe0fDSNmxiLSd06n0Roj/bWV/tdDiGdcc3K9hVs3qWxjJTXZCDL7KkTlUnuPNHUKW//r2rP4qzoS0eFlyNzD2pb7Nn1PwYVUuJIY1cOTubtakm53m0ASgogGBWsfgjoA/+9sQSadUeik+9bmnsx7dX9dkA9Bt/DbuhwAUNs48kaMO+hbzQACV6VUqIhaYzt/ltRAeMK20loJjKTv0a3abC30QgiyZdPR4FUuNPJh90XbHWb9XTed2gh6UPT1Cqanlb1w2/xilu7oigB/bu5tsCiBhlmX8oIMSJeXcdnHtpvQkPZOXf4FWirAI3vpc2JsARo8i3hBnhaD6luyN9qOdsq8tYe0sHJjh605CXZQOEZrHVxtcfjg3ot2HhaQQ408TvCcvNeqrkTSzT+ma2S5W5vbV8Q0VkMntAA7qGgRJGZYahpCUbT4VI6fe8UfZgZCTxvbL9kkAX917OZZmF6DCJruW7ybj6WySb//EtHQkTS6pGBILcTnAsUPPkKQhklsOBsKIdxE4ABO76pn3UJNPddBVD9hST92xC+BNwHc30O360kULN8m6N+0BVla9iqLk9mv6tlXLPebSqnFt5Gnwoc38TS2R1ZE4dfwReRlU5Xv7EO9TsbqL4Ecg0E7WTG5hR1Cnz1B8d2RrXDAzNPB/mUHKZMvNGf3WT0O9BZLjzegTSsBHt0MxH7hTgcdfYYgcdzRy1DtMVsnbZznPQRmD6+F5Thnc4Yn+yM2kI/ifMXVwtTdMHYH1t8RsPx3nvcb3bEjtaAX+z4cC8N//j1SD56Zt4UR/li5fNKiRoVQM9NXrBtp+dJSSnrvKw2gaWwaBbFoV3p92KvEq4825iSvlnD4Gpn7rKR+QtMfOdhpD3HM3/ZPsJEIe3dDoMOY9YtrbBnB3Oi2gIBQCjnDTM8fYH07eHEc0PSfM3yfPKNB3eaVmmisURqq6QMy4NZPqo2XyRv768fJQlrwKCylH8gFry/90tR8ZybWmWu5bDEk+SuqH25IE1Aj31bXDmPq33WYO2iuxEuOflOsxgzffIFzgLB2kgKpr4U8xLf5tFteR/J9cjcoc1ii304ySeF+jqTK2PIOY6+tXaDsEiIlSv5XVQWRJMvrFNFzofPtfe4P5nK0sNIrTXA+ieQyzQB3sWIwhsk9dm8HIY0qJkBpe36MGxQm1ef9cmya1OaPRDog6piyB9AThvbADndYJUpUzHQwSAFUvgdpCDenR1+eVMD9v0TdPyxsRbdeWAtXt5YEWZLoyw8NKU8dudav4KZ0LHVQPsMxg6hNd/qeSI08EKyMdRwhKQuestion 7.3

m8oE80ttb0flK+tIo33gvNwJwB5sO/hL+mmdphHFN/GBVsfR4ZA3HZuoj/y3nZYyVjt/5DEF9+IffgTri04PkYK4Nhv0AgAtoeAyiLMdNQxOkKoxH9+cTD+Cl266nRqc7R2XBF8dbpyG3sRbpadH/KvWjLqJAdi/zcZ9r4mENfXqO8gbgJHgX8w/3untV4Cktlf/Z8y/R0XIE4dODiYMA3sV54Uc5uaj+vYlA0I+aWq4FWOq09lHGVc6GllBPsBEC6pE1aYuS9hOlYSP62FTej1/bK/ue4SJyEsOgVJgjTDNmOFXzuXcK//y/MQQ+MSl03GhpBA4+qoFte5L5xfE85xUOtt/3zpFUEzFGwqrPa4qcbcwXD/ywvD0eWfh9E9JSulIIZtqMy2oxlRxwRaq8iLSU31GeUMsY5zf+7+TxY+II1qQzHjb5k9kd1r88bjvzA5KecSv3tE4NVFV9A6hNrE7SeAOlA25xHH7JJ5PHgUAtdt31pkPVxUcZppuxc08nEfAoD4zMhX62ywLkOtrx121yPQI3u5SAdIBFtDfRD8/iDvTVZFNdUWIvGmrYTj69j4qnC9C/UnEr9bN+7mKfjmEvDd/IiuWMN60s0paaS21DW3W4vWYeWYF0PB+GJII+uzX8JrRyTbr3Uf692PVrKV3OM6DMd2YsEJ3Ik06X9eSHF+pr4RRjexDEzv+CpJG6WVMXoa59L5tCzhnPRp4cE1JdujGnKYBX3WaOFbPLyWzPCK0dZrRZyVJpJbNt9m9ks8KExyLEa62N3xG1QHqRRCg12RHumH6ExJ6ZffHV5h8MrMHzRJqXQp4kvw7mP7VPpT/QMAb0N3dcljhBlgA7DJIGt9FIjpn52ihck0XFz7TATJqc3a71MFu22ZkhzlpIiRONDnBFz4zyJLgA2sob+tF5cn298I7tbmJiYErDhb+OIO7TJl0P3QfwN71a6bj72NYwktOnxTcVXNNNu4Z1HLf3EQa2OKrcY2kjOKrm/YmbKoP8yrMoAGs3vYyyLwIMtqfTxjiwSkCLbWX3odb36GvoFDDFDwY8hhFyePE8fF8XAovQertJ5eXSA8sKf2ORPivgZiw4O5rkHanElskZtkB28X+hD6fRfD8HSL7uwHb/xMuyssgpuYijAoeEP0yW6AjE1rHPlSUwgfVRtwZEkIVFB0D1Gxaj107LW8Z+T9+m6NvoNau5khC7mf+Zc8DYGax4xxCvclJsJcI/jzhi5dFvAgOBX8kwCl1QfpVAoLe5fdZiU5D7Ot9iUoQ0UisGlRLS7Nf7Zec/dDdW47+2j7MtRM3yPG58wso3RwLqqiTL8sJAoFjl/x+eaCshqNb7ntDve+kkhSpIklKF28NehXAIZcXQ4FzlNGKzrAhljbRYX2l42fPFFhDE2l1PATje8Ry7lR9MxgnOivjHmCNwkcRfOybkDmWYtG6Km7pJzWY4GD8xboeZNG9yqxOoc0Ekn6oajcZcb2YVvfzH3WeNiLtRT11/qk2BD7potzz3RYqePnSB8Z1CzSSBgiSnRIwPNcLGnIWhHBUgeBjD28vY+vGmaV8xDP7NO3lGbAtBfs17KBfqSanpTuQTx85NPBEylJSDutiqD4uxjlCwKmDNFq1oUnGhZA3NQvVCzLLcimYHHDEUpNBmU4481UrD7ny63C2dy6/iH8yeikgsA6aMhBQWVBJ6iSRvgUTVDzTvnUuhEhnxuHnrNSp1NTVJ6SQDvKhiHHLNKCH+G07zpN71r0zAtFyZ7Lx8nQLUy45pMVI7ZP/eYmHxdKcnqLJcywucYDiElTmUpFd3G0od4dxZ+LCF18fNN1hD0AL7kupExzk0dPoquyA9jH6i84wAk65rK4uwde9Xi7WdUKo5ZCGflItanNZt+/5Jy96LNv/6uukgeT4f9nIV3V1cDaZXrKwQQ4duQzvzuXtLJ5rbF+FJdPJTbP0hf38D7NQNQ7SBOfsHdjNh7ux6/8yEVlC3u9dgYmxPGvn/qOXAf1M3VBoRF7Mp3dsgEVBd0jACQEHydAl5uiU3SdqXT1teRQddUPuVr8zlJ+BdAjL2LjBrRhVRfMGAU3K63e/ma48da8qAAQaikbVU2FsoEwF0B8c6j6FwAtSjgsu9gMPuLdvwTsMN7joGneJor129fY8kD1ATKiW+BHfoYcaU++271hlgCT5WCsa7/XgV8uQWoZW7NVFUKM40lBhGRZFnAvA0kieHP4Oun10rx6+9AsZcjZ6568Nn2poPV7anDMM3kZ4X9EzjyBYrVNLX/dCuPZzp63i60BQxWUGUHwG99laD3uAhvCHme8nScHWXLWFVnus8de2WevfB+UyVLLhSHzETxt46B4Re8nIJuFk0vStzvTE6Welcz+jJTxjTjdgQJz624uA0gfcCoVxtTIqSPdl63aZUM3RLksu7PNRHB+oToF9xVvLIAElYW5msUahYei4x8bq4o/wShT6KtEF2kTZUCKp3+QuVai9N+9Eh+07PwP9ZLsuCbQr8NdEdBM63xUrkvxkoePhJpcZyEQrEmuth9PhJdvICJULaYw3CYB6iOMaWNJ7HABXZ8D1/LYobRYpekX4KiynTwiNnc/HDmXl2BSkM5j3PEOvCjlTGjJFmKGbb3os5PyXHGVEp1o1kzkZkfV30HcsMpadFxrAtsNcT9DmBND2rjJuz6CkeX0B9T9G8EkfAUWAKxDluPdYXFlp/Lyx8DIfrDNm4gPStPy1NX26j1vJ7wVKL4Ha127ndU4n2kCe68ZYFHCe2qTwiaS3+Eax47Ilx+5+cJtimuq6ox7Kh7N1BDcwI4rSbVFDPmQHwpQ5KiXD0ltisOzz+UgfixS3uqiA9uLu9vllAiR8G3THxfS25ZSlKsdgjFXbf1hx9xEq1aBJ1yFqvOSVF6QqBA9YM2dhew1Sc8Ygny6fFyXJPsTB4L3kmHcqmN2QvJJcYi7TTshZPvsicBIefu+k8UILMynABT1GlQOPwAJCELwoG47BAJ8hpYpddxbKhlBIDmDWMV7NpG+UxGaLd9NLmWs8qvpqbEp6OjBnNzXK+8jerrGYlraxW2nqCX8LKuNCPeVuPzb4P0mIqhw52cMlrsN2YgIxoszyShvUAt4rsYon6gg5ZpLMBN0r0JOYQlCFgO1+BYXQIoNyYNoysf59X/oE828G4XzbPjN4z6ikpsJNhiB+eFnZL3OYFuBwXczelEEmS7zRK5fcyFBn+2pEy4YFD39NL3TDgTYY/9kyek+Q7GWb80+jZJjdr2l66NW/pz+4CooICHReNElsNPpEULrntyvNtixYiy0XDd2nleUxnHoknuaBXZtrUnRSYKKowRhfWs7X6/Wr16fWBtT4YSBZZl3yXhXCN0zswHJr0WASjLbfB2kgF50AmODOAcE+eSslkqWyLA+KTZ6WfO/eGm4VyhlpnpLIO3joHNvg83JiirWlagSHcjGPICe20++iu7c9ggwLq8SLPpo1AiA4q+RT8k3+SgTINd/5suaYw+r9f8051XXftncMv0wY8P1m1y54NY6/jeb7mfqdHz8iV/spr3QJS3Lx6pOCPxSQuCSPJ+cGpDW/BJIkc8rkFdVeeuXI+FxPEb8t76iHKqJhCe54ikhUacNFNLsiPCcBkOSmG9B4QAdDCLPIfeRHYXkLJ7F+e3I5HOofut9x2hxU57hZg1bga0RpbUN8P7z/1YkHQPYs2pTeGzc+NXemlLmVVjcjoghXJ6mh9xAGsncR1np5utEgBAYdz2QM1Wl/6w4m9Uw2OvDcBI/TEOBxplWN7u30JsWc/MqU7IK6dLvB9O+wKmbQ4HiBuHNImZBmRSi4zk3UWImSY6k4FBylj8+V75+Dnvtk9A9T//8N987b8tYXoZEap5pKb+xb0LbouU+IS19s0+c6zfFDATOZTb5Fj8BTrRy9qA1CMjIMaqsnihJ2/2GjvuU75oLpF7/HVn6I710Wpe+7vph7syjKgEhLl0RhcIwAOObR1ljDzQOhK6V999CSqz1x/99Jrt34cdrifiS0M9PLOMVOkpbi9RAV2x0NC3qUB+Lf8KzX4JUmuus4oZJMlY+IN8MVupbwLnHEBEN92xHicqKaOO5nMKORQTAeui8fk2LU9ajRv4CNYCBa/P9WrQKIbIQv2/cLz9I0mziEMGbAc/hS+qcfJRhRuOhPJgvEqrTMikG31lP9HWYtAgJGQ4Qkmh8TjUSzrx+Tn4Z98Zc9R/xihDHrQu7H8ufkIs5u86mCh1NJwk8VGjReP7wWM3rPvP9Zskx6gpTNtpIIBUGNLUsN4WIWvoWev4hs8afm9ao8GKU=Question 7.4

KR7GhthhOH64FyeoyZDtpaA9AI0b+qRHYOJ6p+E6AfKvO5bBrYuhWH9ArqLRy6OOFCZYgD0l96XU5NCo07htq/fMQyC/FYEDu658SCRGmoMZknlui/F+9/JyxgTJSk9hoWnV5Kmr4vRuPr5zPrhzbfNRGIrhqHl4lrpLkMnOXyB+l8rgwT4s4Ci3fA+rdJcOvk0BOqD55kqAHBPRMtssMFBWD1UhyTx3nXxRU8++TboAm86asAAt4jlr1SIM96xOcWLTQDNj3IMxSFBuEynPDvzBmJP0nC9VMklXkTF+ALAN7nPSlFjpfWMKhGX+PjiFwjH4D09xOfIOWqaBDfJF+Xr6mxF53vsZKtNzgaokiBadBzu65J9lNxFOuxOL6/S8TLumZf3WGY/NCrgYb+10ZnuKmvF6zYLqmyM6YOpY63b4XJMq1PCoSRo6SLQ0VpF5gunTm4hT8sHRLOLWkj/yC7PN4WNtvupn8zkYltxsL8YQnqOI4T1kuMF+jreqxqzzlAPxyzGd7+Id1mLE1JIav5MFOm00kuXmWSbY550twcAY4yiQcz51x0794ZGZQPmfOejajU25xQvPOU7UP1Q+m1tXs2SrS36QUg3UgBh+ZZhRhJY6DVTksXOn1nf9cVgs/0XV+4bO2BEirkE0pJSR5FrCq/TzOE5mKhtSAKHSNpdOgWbH7lbvepuCw0Fjj3EVJWqWKShAYAsDUNypE4Nxe7CMTgKOfoxyy3+Z2bxa1BEx08HI9JsqC0lDUJ8alzug483zOkL4PNxXySHsAcPiUSW7f+h34i0fYfShb/9Rp57vt/PuPhyq52inVVM280bVcPqG0ayiKRD+0uwvJtWnSfit4fUtK38IVjYalS1WCwcvhfbGFMEmL2sas6KZtIV68QDr1aEBawGnkkCnUDrIyURXVbo3P6nqFKxpTax+muHQMUjXb1AKK+/4vh/T6AUj6Nj0DPxQ6oEh8iDWFhzRMvsWO53b/TRoSDQVV/QXU9tOLDIaMnptTGSFvxQaO0C7XOv4ngZgd11suhxvtxKFJ1Ne8yCG9U6AeRsEgpsSZIqT4SQboPcuROU9cIpsbLZ7V5gxrn2otVKMvJjFKoS34TyDYA2o+VymKAfHpv0r6AWHVFKxlrtYU11GIbXpIJyqqIIGWOqazxAW3ERqJguajINZXjp21n2kJv8wXQekU2QHJnHy9gdonUkNsVhtDIydzI77G/Pcz5nC3+SC+fsnKDRLcw1PvOkX3SqC1BdiS332SYsyWjgcdgjQcsYer4dcsq2rgs9fLxvXnClxeXOngx1bgJRwWUrhrD6x4q/D312Sr7aCuFRHtMJG5yGAfLEi7TlYl1jWf+Bpl20ZLJLxBekD5apPR6qCpvMQBqdZ7VgL3mGPJKd+QQP8NxC8zsqTp0x0vbNpovDfJbsweE5dB7wxHeRzMdmzVqD6ofyZdmlZXiYE3QA+6wpggYW6/gKqzLxX3BUqLOzUIjY+aW4PlEJ6bwB7TWXQUSk5SK9TQmsP9RpNOkMyKl1FakzbSks/fk6TKMWH+yDhb6cnoaWtOSRa3I5/so9LlwfFddeYU+FYHJBqMrrQ9a8bH+KjgxUrt/A7HneUkIp8CFvcQRL4s5KfwGdE/1AJlcpTxhZR+sbMbhw1gydN/mWeCdSbu2Ext/JHiZ7oLox1sVNGixZxn22q7CuLyQ0mdijJ3KhV4qzIvPHBQLXNsKX6Jcy/k2IlUBKUjVtStYIzK+g7KrXwDtE1gOCIgrMtlX1ZCuZJgJS+sQEEUySNaCjRagJtgxU4tYCT5CXDwidRdBfLmb1v3mIa5ox8zBK57zEaNUydFZaTI+xd+cbby6UF+rMele9kdBs22WZI2OXKquJUGgn8n5BrnuVKsjad1sNKOW3T39spyNdZo98OSamzqOaEGusq3YErYhPPWfgwiUIh2PwNNwB9J8YKgaWJPdfAt1Nv5k+PFne3JMhsCXXJ+2GnCL4KidACZ0HBcYzPOfF1IO2y1Vuly0vPvwElwgF+kQj5+BRkXVg8GFYhExLbRBvqARM3Gg7WK4TcUwaBSLPLtwidFYngfOZ1pmoVEgfcuwmCZUuJHsMZEgZNbl7yJ9thFxo9i7DVCUgt+AmBiwVwOFjCKzKIZX2KnYB+pWC+bWhQmJp2a9yi/wVv3/0OynALOBad7GlM4BEag99PUuVBU5IEdihPbKBdvOMfKuEeuv1OInpJ2BFgWPiwC/gaZcVGSW7pBoekXrKLqrblfuqDdy46ZWtNfNxvnxGeOMVq6nkSvPqTujOh6MdExTUgoTv8CFeFp3tnFNQXHbRchJJ4nJARMZy65EtwRC63OgtZkT9RGYNwICgFHkPX+1Ywc9RgDsHjU7PHGWO8Yld4wOW7ugw0yd9UtFslAMuFecuzGq7TI+U=Glucose

Results: [Glc] = 60 mg/dL (normal range: 70-110 mg/dL)

Question 7.5

1w20jwoU+/TN3N9oDCiXRgrHcvUdLrIrKR3XbJHzCnkk/HieZ/AjoUeA6YUfhk2k2dDyq0eJA6/UPDtbSB5G4zufWyareYBaoNImVoWiIh6T5yzBCwRV4ldi8fOkPaTVfQyj+QVZESC5fIS45T03l974DlHQSKTFVoBkapylypaySkljcVOYidu8kCzZCiRx5/zF7DH/dThKlZgMsCOwaswuOYoG+rm22sQRk8wzvxyloJg+OqCJokYK/oApmTpZuyQ8JYw0c1U7uG2IbtGHzxYehQqhE2GlOMXBzO3cqcsXiT8SF34yrCCLxS79hHSpQ+rnQXq6QdvtJPzDg8XqHUQdtMLShL8EUCxumQoV0vbxILG/0BOGueGcdKR8WoQK/vnKpRN7o+HwIroBKiT+4WeB7PBG8VD8OLPR5drjp8PEsphxoWuR5q9bdCEwUQri/BheCMeEO81Vr3THndWzwoq/jX3BBcs8w+GCaRvoR1Z486i0CEyW2L4EWCFlRh0T79CDMcgRSXOe5YchJF0P4RJBHh0tN3eobj7Iun01rGqIS7fyWIfonqqXlLsoCIoZbp4WpxrsW8F4Dvpk0Whjn8vNpbkIkKMX734qzkLm9yqC8rKsjp3oQKME8I++hlUdt89DiuYsFjz24l4oHGYhxcLBeeSSD8gM67MNneEfBHAJfBLuin6PqqlTvZWUTuKb/YMtdBDj4C2GcujW02bs7i/Thsvq/ZJz5qIjelLszFHURIZzi6c+kA15mWqBYrBLfW/OWiMy/g69JlGrp1wLT2OPSpleBlTUMrYDMI0x1p1ht3+UN8n+frOwDt2faC/12zcGW/y/h2ht8y02oSL9jfKsiAFgnEdGhQRmSvPUq85K+9JYveHpesYlDQv8OeUbkqwyMIBQxFc3eZXQqCl5/CUrjM2Saurt4TQ7OlUA78KDgyvqFDo685AZkTE5GhZQmIVsFZgmgJSjnDIEVitfJ2Z6nv9JEQ0JzniLstv7yIFq3zFPizmPge9fwJ1P7ftDL113ex/I27GQ6NbEYd+A7dOKeX1UC93BiG1F6UA2gRhkiAdDfkF6clnEvUuypFGH+TSrJKBj0ic0ux6PuPSf24eHwJ2KSdJAuXg17Wb6/EN95kwCa8OaeHs5VB1xv+ZCSs6PFRDc4miSgmajJ6P7kxGononowptq+XpwqhBDa8bCtIXLC1Y7/L3QHoEnAK/tQxbV3ZtgMOCA0HryTFWauq1f0ewfhBTCQMtlZ9NRGUyvD9Kr1GAnQOPEL3K7Q2h4zyFo2SUjBJEzzHZyLfIe5FI70TJwKm/7ki0e/5GlmL1glpHnNpkJO2MiXQRz0RaK+oOsWtigysuEtHY/pNYbRQmO0v7+e4iX7brrLsDgrCpbir3FdhT0I2ynNIzwdSBQOSmXChwEwxrlF4I1TWv77XAcvC147XOWVQEb6eF/kNny875+rhZRR60LAFobJWZiKEkBzTMqLiR6ryOu3LHKUFN5GBY3RlGz7H79e9ocMnVsik8DxnI+MFG8bx9gGcFvZ1xAN50KdjQxQFdllKPzdAnkdj8/gZH55HSZ0KqRS21D6a6yCSB/hEbWj1hE9G8AWDwVUBegGc3SRDL/aHi6jLJ4pifwfOcVub7AeMZH3bO5227ShteG3DEXwEJGM5kuI4Fj9NpIaQ0+JPRRmNqU2GoRjHb6ODDkZG2LfLC11OKpxTPjUihkiIsbUNfFaYnVUkhtUgUIgDfsqUhzUBiZCC/E4YYQlQRXqCNjXzlgaCt0Oi78VG3btuD7VjtT2u26o0IuXa7gsKJGn76f9wz7nAO99C5sst2nTUVc/uLar0gMVV5beTOgZVgyi2PE1uqLQskvbi5CXdGXDQfEDBymqPvb2bbWmT55h3kCmLjEZp1lFpKLbhu95g5GiKixgyPdskQGUn/ICIxNr/yfCDb6xlTpM30/+SsfQlVkcwXBzAJuFxFCODd+iqFJrsoqLyaFQ/sH9axdMxAzziKv45QGqUvhc1KI3W6+eZA9unKvtVDebhcKz9YcruiPFXCrf2bb5RvuGK4xZgpMXhR0pgZ+ygXpknQtPS4McBrvE/h9sue2XZnyBPhdk2X8yLBeiwPNwqAt9K3G0TDDJAzoQaxDyeuWE0Ut7lId94Y1r7vZeOeeUDF6Hn+OFfH6DC6XRU7t3XZquanrNuzzf7uhBt4PKlL9keQChsrCTXh2CmAVOmj3pknlUYR5M8dk1xRpkR4FUjjmOkti9GOAgWQp4/e0eGm9xXZ2RGpEJfX9MroC2JaAKnlDz6s5q7pTfJr28vtTzpOFrP7263/uwWwxvnwCVTLGNIRCjMe1asixkibWRBrlFy/+EaUPjPfL2O9k4sBynXB6KfrxqwZawfS+fx1x99+jjPT608ds8i6iLLMotyrx4XLViWwoRKr6JJEgMJrzdL4HzBooSikwG4eoRrWg8uYrXoXyPjEP3UgDjZOb/37CcNvjS5ZvTCdCyDoI613NWcVWtcjOdRTU2h+FQsk5GTJ+loCKBYiJb9stYJs1YnUXi6UTKxDtBcxFJXxpTZuk4nAEPFYzLUqQP0dR/PjyaWyzbLQS7brKy4pMxgqWEsySFz/YjHuFMx2YGZ7V6FSY+MAKLVOLlXVRybiSHu+jGmIXFn0CRs6t4vwMpk1pRt5HUc+Fvu6uJQ+oq6otjvDRjubsoWdk9xIFf64k3oBvHlnqlD7ngcCx7x5rmZ+PRmjFk/oIsMFn8A==H3O+ ions: blood pH

Results: pH = 7.41 (normal range: 7.35 – 7.45)

Lactate and pyruvate

Results: [lactate] = 1.0 meq/L (normal range: 0.5-2.2 meq/L); [pyruvate] = 0.05 meq/L (normal range: 0 – 0.11 meq/L)

NH4+ (total ammonia)

Results: [NH4+] = 45 mmol/L (normal range: 12-48 mmol/L)

O2 and CO2

Results: pO2 = 88 mmHg (normal range: 75-100 mmHg); pCO2 = 41 mmHg (normal range: 35-45 mmHg)

Specific enzyme tests

Asp amino-transaminases (AST) and Ala amino-transferase (ALT)

Results: Both enzymes are within normal range (normal range: 7-55 U/L)

Carnitine acyltransferases I & II (CAT I & CAT II)

Results: The activity of both transporters was found to be well below normal. Expression levels of both proteins were actually slightly elevated, however.

Test cells for Electron Transport Chain enzyme activities

Results: ETC enzyme activities were normal

Creatine kinase (CK)

Results: [CK] = 100 U/L (normal range: 40-150 U/L)

Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD)

Results: [G6PD] = 8 U/g Hb (normal range: 5-13 U/g Hb)

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

Results: [LDH] = 150 U/L (normal range: 110-210 U/L)

Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH)

Results: PDH complex activity= 2.5 nmol/min*mg (normal range: 2-2.5 nmol/min*mg)

Measure blood levels of glycated Hb (HbA 1c as a marker)

Results: HbA1c = 3.2 % (normal range: 4 - 6.5%)

Question 7.6

e/0+SFxcfUHXtB2yE+4f1OlI5Hu90uSXe404X+KIF0Jq9UA/ABUoE11kRmU9tPbLZLGdRpXcFMj1MWXuuNguKgCTLWU6wAcsKiNdrDsNoOEPD2cbwKfAkdwDRlzFGIXGgJ+b1LX+VH6VbxY/Eiu+gtaTwGcE/d0Dw0jkuIRCiTXs+XxipI9hYe5v4kPrKSn5qKsAbelirlznf8e/RoVBdvTA1pbOdpPXvSo2S/FYizUw6F1fUA50QgQBFDwiRmPJa5hqIDtioisgze9sdcMUn+NORMHeUaZohnQpqWDUTyRhuxP5BBgjr+Kqqhod9Sau+1Hw4QrBnVB0Lmp8kJEAboo5qTC2in33Ul+cOKgJLdbMI/mF9FHucyMy/ewbvdeLXpqJJ6bbwH3DBL9ltnTWL1JLnD78XMK+WgiQyuah2GWCgeVFU+FpY2GeLCpzEjZv3T50NG5ssNDUq7qRjoN3L6qyavpft91bvrHyVeGGEmtUsYr/cgrR5sXQBx5oz6aTXo4MGJJri67VDLYAbsw1gzpXAQ7ZOgEMeO5H7rqCVav10jertE8dxOFb/gwnxHMq0VR3DplJy70qIEOROfq8h/YAxz71Ld9E/wXA0pLzDgupksC8aVX2DMdDCUMGj5WTRtWEbWyAe9qjN4gy9C2NqNwBqrbFH02+naIt+guc2VDsvRA2yG7ipFQ+vw1+5dXQje/88LEr0f2drwEKjXl7ze0u9dGwsEPdn1fGVukyA6kErUczxUkkxfzqWh9g4db5jZm9og4o428i1CwjuA1Z7jJHjKpT7tb4u2gUO0ssJ6J476MJ31hk04LMnpO7ne3wYfit1JGmsjDewntX/Sc5nh7v73+fBm6Gwzvrglvpdhb5mADulEakp2ss+dG5X8bjQCe5QewQQoF1uai7MpeghS9QMmx9ELeJEtur6bsiUTLbJMzPpjUJ9ERQ8i1ISj2NlOUghXC9AaNzfjSwFpinugu6HLfdJz9OdCnXYTV/nBfmCaemB4H6Kl2grMGrC/ThM1/HQ3CKcSt88k/gHJmZxM9UuHNcBcx9Qpm7dKZZrbxAYkSzs7Oh9WYZeUEXR38tG7SgAMX4DL87Vmh+oYp9yYtRIYy5SEkD1ujv+1/4qcqJY6MRd0OsBA8tb5iJwvipgrzz9W2ggxXcH7MCxP2FK052tMEQ60aTs2ex0yJvSyVW1xNw+M1vbePG8E86SMwl1C1Igr48zw5cFI2xUGJNbuyqACgS2mp9AcjaOMqCGjN13KBj3YOepW847caSVUfq7z6jUnKCGaPYyKCHnPO1hk4ZvbY3x14q79qB+J5Y3FLrIctxGKLMntBRvkxB1Nn+q2rqNBCsLXw39StTK9PhiHM+xW9akTDwhuQ1Luqwayvyhtql4wV/+AlTk5PoK4omamEh3JWObEnI3kheXA/IBMm10gs=Question 7.7

TlHy9n/b7x9OitYubksHnkkZ4jd64PKCSHWM8K8tMLfh8f3fohxwyTg+TebtnIFnEEBs5oMjoDQV79E5qiQX9dhyJtMwuaUw78LzVBQzByyTbnzQ2Quo7rXIf5yYMmsWmXqwGPqaxW5fScsV8ak3O6muI6ZLTlOrs1Cxi8jlum4FfjAlpdayOMKE3+MztkADRWOkozQwRvyWV6Ve7QFVNn2AV0Ri/xveKZ/2JWmzgcQbNqTmxe9heGXI56hb6QT3rwuJv5yT4ydx1nBlYpl1UZJNpyrHhO1Nsjrc11sk/KXxKpNDAnrjP9yoRj8UpCySJig/wY7+jJpNz7B/M+SiKPejK3ELopBQU+FO5XVz0RFQ6MH0elkXIR9VQwMGqmIv81Om4SLvWNQhIjCFRejRYZylV7xwijl4rNxH4bH1TNfYYwdXiKhrB2PP7VN2wih2IlGSIWOPLtF1hDKIhyJTq75n4VaRvkZbD/BaVvMuY2D6cZqrWdajEYQKr1C/QoXLZGAM4pvYdMjkd/DAckEglpChyx7X0+ENSBg2ysWEZyEY6cgvNJNeT3y7VVzFpDx6FY08lT6p632f3xpkRzmvnibe1huD9+bkuWIYSvIIiue3+n9faQrmpPAEpbZg4rNkGSYeDnYJ2QS8D9OxO6rHuHjDIWBAsvQ1KrXnvQMNKNrI7ikIrmFZaa9qgnYM+9Hh/5+wshBK1Sa/e1e4I4a0fF2D/6lQFZub3lhifgP2gDRRu3svfxrxdU4Mn/FU6vRMl06ORGs1FtySTAY5ahh3FME2ALs7Xp8cb4UKE84+CTp8BWlalKSzrgKoncBJ/Ak6ArNS8rRnLJC9nNbuJ47fb/ZbTkwk3Bjt5OHKErbSwI/o3R6I1z65uEwDzZQbRSaJw3bnXzWTC7YtRahUksO37bScdN6RC6op5bFUGV1IHheUi7w5iuJSU3O0/qmqWqYi87LzOCfAlh24v21510a+AcPe7IpeS45hrNkIlWOiLtkS870eO2u+Cdd8QbS4kNysDhi6WOAUbbl0IAtEGE/dNmkiHmFSZxaHlEvklM5eOFixgPwMDeNblKmDk61k/V1+ibViHFO+pswLVmfW3Gi96UV40eStqsH1MzFdOpnGaqNu0sBh2QNAbWgvcbk2TJnoatCdyCnPCniy7Yp63+CzHEFVD90r8auyCbHTR2FjI/o+jFWR+2KPQQAIW/TJjUXjf2pSA3h67fa/52QC5eCDOriXoTx+OCXpQwiUOi3jrcahU1plxJUyCxHrzIz+NwfW6+b6Dimi6yC2pNm9QaqkHgOfGpJdV9b+TFA5idXZ6ekkzbgUY6LRJR50S1jCCSCMh3/U9phInmpqmR2KoWpnQo4HTkvsanBe1d52hWViLBvHg6snf9bhhBVCikEYBC96cCV/6FEXYRT9bK50+jTm2sLjvZQJEa0WN0+vpeZZFWtohOtDbRwuVKFPzuKJQJ+/HrI2Yp/ekECHyQVu2REclTLb5wDB6juUoC1jLHpY/gFFg3jhkOyaGUtixDNhAAtC1qzRXtPXTH9KEFgPDs94oIXtoGfv3YKnoqKI2HuB5oiV664Ua99vocMNvejCdl0WjFi6jz/1BU8TwTnIcXAH1RlNDKcoPGIEPngWyv6ErB/nXHt76ZWoOqIAyJJROTr8szwDRWs0lp1KhMt3jSG1GUN/w4gIWmTQjf5+LFInZTXtyq6H0yIdNbTUUrunN7QV3jA36KnZqmhIsPvGzjJbzuj0ifgbweo1XdhcH0VzSS37b2GlOVZrzXFpeZDTfjtu7QGv576AgxZd44++rNSANypQoiWoWpk97XsKqN1SZnyk6UICtSAL45eJnlbwPQ0NuRTg/AJWmGknwm/1wt6Yqp2srESFXNEUhfR7rI+C6Rc22UExVK/qgL7lOSexBz4JdVx0WEoNzHqFbiEpF18j1kyiomZtrCYx1WSDGJnxdJxSKdTL42TYv8zcq2YDTBkW1o+vF7bfAvG4zl7PFferdHIwhn0gqyafttLdTFfY84Owx5Zs/UoDVQryUnXJBRDQMsKhuTNOVbqrmSgIvIbZ55yqLzRVBnpTuI2H59LECvqMmvmX3/qvTCbr0MLY4t+CIttYoqEF2UjcXu7z/GOlt1oey44+wtTlrcx03894T7iJQcR+kjJ/u0WB+VScOI2ijA27C8n8zWInVwDfl5s3dZe2i1quWasAq50d11W3lN37wnCV5Xq5SdtWUWF09WKBvNXuBjeqeV+ZulmAdSobvgWH6mymeNO1GF15OmZtOtpuAjap+E3Bi4iMqre6Amehen2yR/h7eV1+FWaqnao3cQuWTeEdXQjJFoAAijN35WsyAUeg8uil9nWMbDNIEe1qUy3F1Lt0yfxqImb36SA/Awsv9Deje+qKASmghUE+Ee7cG1CiiOV+adCZonOJeyoe0X/e9nnf90HWkoFBQkPdu4GtxlpCb4EIScSfxk0L5iThhnNpf+vkqWj+TTEnmaxF8OlD+5hjFpmhp1u77/1Vdf0QkyyX6RUPybJBzj8RXlNhUVdAei2lanF1/3zC9OEOMTBK7X4z8c4tONkp6ouvpIi0J8hHImbDPG2iXfSPl282n4aayPpR8VIPDiVIP6pF+O4TKvxMtP3pY5voYs+zFE2JSrQV/5iMRki8tnGUEuwaDQVx7zCQfb4GtIuHAMoYVCwvA2oq4A7TkKgR7PM17/u3LI+tB/lX5eC1mJlZo9HCiWNi1+zpkmGvR0cC7aVK/tvOS+xCX3U=

Conduct an oral glucose tolerance test to measure changes in insulin, glucagon, and blood glucose when oral glucose is administered.

Results: Jessie fasted for 12 hours prior to the test, and her glucose, glucagon, and insulin levels were measured just before the test began. She was then given 75 grams of glucose in water to drink, and her blood was drawn and tested every 60 minutes for 5 hours. Results were as follows: She was hypoglycemic when the test began but otherwise showed completely normal responses to the glucose challenge (to be explained in greater detail in the following assessment questions!). In the very last hour, her blood glucose slowly decreased to below normal levels (hypoglycemia).

Question 7.8

MPFCQ28YyMz/OTpS+3IZHDIHWttYJc0ZPquDrdhU/fUAwB1I9S13DwGGWMzMznEhgMFZweq6caUp+ObHH6GUm6n8aoRcLSsiQNkz4YOFyqUi7vs3bU9jbJWdgURp/6X35YF7Q4ue0OFLX7IFHDVPSYxnFKVXjU4Asni2nc4slVm3s5T+jjm+BP2QIfk7QK+Q4IQNBAsSEWmTsRuGtbv1jLQBf+SpUJw7FMOecE2GfBJWYS1eX6XTNriHgAzh1T8nxpyhq52ZSK/fK7atWKsDq/g3v8HEmjJvsBJENTASSbBi2weNTyTKRxfYPAHXWjuITYvhYEfznw2fue+HB4PqfBIMOI6WeXs4kYxtBPvVYics6KIdqqbxAYPP16CpsEsFGTwSGQegHLBMwZCbrMVGoXrtNwTNPA1btsN5oPzI0HwXS0L81tJoHe5I3UB/+aW/ifzWZ+wrEJVjRVD2TvuMZ+C0V/b8JQSjidHSOy1JG3sfunFidCA4BfvVMze3tc4Uj5HN9HVjmNyRwHzNc24jf+g8Ui7htH/234QE7X4xqjRiN/I5XydQKHvSzayU3LIgUyUqKJrRSJ8ckAj7sRn86YkMUrF4hXxI1Eig563Dpjl47/hLukPLsdjQ3PMiLAgd2tFeAYEQdAo/i+psvURs4nHC8PDwKBf0yM1Vweh8w+c7zk6N0kDcLSliwIP9IQRuQJ46QDamIXkNC416f3uRsoS7idYNwivpo0fGVWy0H6iUJqHfwJqWvP5fnOMzj7nhh0nqXWNxAQ3PmCXH4GmHLz9LF4iAcyj1SQgMK7M8PClKNi/WnTsU/e1bvbcjpMJs55gAOaKMi2fnuwl0yDmD3HsnDm5HGNbYJyaTN5ZwBWsTnbRvitAmzjmVXP92BPXx2cDPZzFp+bT7EJqtBWXYQVvc4AfoXibBtnQHyVZIsU5wOSUwh03R4vihOPRljqfByli5LBwpcwkYHcZKmUtEiwIg1d51GhqjOKoQNCcxxZ4AxZXzsxAvxe+STsaBK2uVC8mOjnmCxFUpcu2f73jO9qkueFep4VLNJ6hpqKA5EVxP6bLByzUpVtLa88sxxsCVFS3awJCqCxL0HOu2FmCTGNiVn2RlS3sQEngpnWhQZR6/JoxIP/bds9y8WYzrv1qp5oIFk5B8uEMJasxfgXIW/Hb3IZoHAc9X8Shxp+0btCUMxd/tJ1LAMdWvkbwCugPqrmFl96Sn/Bo2Xa7RqP/kPtybMb4Yu8IW+dtSijnpwQ5IUIBZc+HavLXmvQSFZGfts111ObbCV3DuZRoIpurQ12xJa3egAshVQU0iD3hITF1JjtQE6XH/NbP1BcfKXm6j3ttS5kLNUTMZn1aM2687X+ISbFTOlRXeoEvUSNDFmu+KX6u7OulCyVS08EN+oolX2O+lyxOcGTmh1m8MUUR3atEA4abLYcEufBlu6UwjwxcRvbqNf9aXBDEBUY2NA8Z6O4VcVFi58hCXSjI2/YFHLAXFJ0dk+7m9tR2CLXvoC+Ka1cjJLtQxN9vCsuKNBBQi0g/UaYQMZ5ESXXNmYbiOGd8GGSKbQce4V+5J0Ux5xpObE2PuPoSjbgzmHsyrLZxM6uZ2iSIOwZc3tGxmyBkAVVCkZrpqgK8YUnI5knV33n5hfxN4bfZcUHaz4j1AaqocRTBL4Jilhns9TLpKyeZ/fl0bNRiv8OgOylpYlQ7HEOhT1tmcN6hyo5lXq99oncKG34WlrMBUsuX1vGUv9OXF9xE2arANvEpP2z+vf9S+FmIZPoLs/xgWMvhcPimjZA3enray3QDyJON10nXxsWEDl8CTRf3FaOrHHswNQPTs0F10HXmAVgd6Hjie1B+bhb7aeywhFstP2pdzNZKJ8bdcpO5CRImZmjdppRh/ZATaCQrMwbWyaFbRkSjdVab8ptbMb5oqKhxgC3ZmcC+K9In8niWSolehmunaBfKSyUf7VIcR8dpmAjRr0aUwSF73KkG1QBZP6I+zPAI3HP0hvVOkyhzzwmRWsZEWAIwywQPjv2tDDSgVHMldoUNG2Zuw7fK05J6G4usyEgg6AkXNmxShO+yfMkLw0DHICInisocczj/Y+LQJRGR0IcOcyV0PiMav4bM/ZgynlH5PTloaK+CXjxiz5h0qCP6wVsL83FOp1ikEy7R/qvRqoDpel/WUXXLfDrhua0MkdlkmBLy1Xxgy0RkN3XparjPipQZ1E5491U+oTXuRlfZORTQFAuvba0vWxb9AGm2UVAOFV+ILRC7XNTLlzmujAwxYJOAMyxCFzCjekaf03cDmQ7Wm6dzp0sX6RiRxARekD7WLFK6qnSr6U69q1WdYPwV1zp2FjVwtHA3c1ntNoKFDsAHCtO1QvQCVlu8sAkeJNmUrApPlEGS/rVNBXtnbWQpdIKhcntB3thqiUuUtzwVKQoymv5zl+/JURqWtfwKz//YGwShkQuestion 7.9

0RPs61JVLXg/aPzP7mAO1EJ0cpX9YMI4F9Bfh2tLzwv3vfsbzrwMP8Zj1IypyU1jouC8SC2f6wYib27AhL0H1BXJzXREoR0F9cAYRgZVd5MFdWi5ID3a8GY82Df9U6Y2nUYrCiol0+NbrLACYV2U6eJjn+a0xQH7snN0Jp0JJyrcV01jzK+wzNsFuN7yUN/dZhJkKhhv7H12AC+2ntOhzXWeTZf3LsiWxewJqAu0odBEx9RCf0UKD3e3fx+7xpoLxIP5PTJ72JTKAmnV6/fotwyuTtvL+Qf+pOpVC4HkqXSYmbXqT4ZYlr/EYKFtJR3bKG8eYRF/L+2e8O58Fkz3vGUTXdqnfs4/qZts30JNENMlwRYk2wdbPWq7SY6mNkrsxY5I5/rIVpIWoFX/v3uiJCc1hAO+jfJTtE1DqPrlOdm9uNdx02FndVaend4vWabxyivyl7J6F0CO+qAfjW2d0Pl7UVA7pN0YIOHO3DsEr1NFExd1jmQFL9dPnJc0EJtXwPfs3OLmQ7MmgqRRqxHxDb6DPWvSsO8nflBVouLY7V0BqAgyhwcpYXf9rh+X0eaowYS5MdQitkpGRVaGLXr4P8QosGGkUiY5H87sbzFfheaORDOt+77zEyhkKHNUEOpVX9jMVSuFLpFOvixFkjy8bjvRQYvJWk/EKh2BYB6n/Z4X4MREgBOYdz1fgTIpYdneeZlgzxgRFsHOhnapE3WUW4/84HIKEhzD/sG7v4VnnGZUbr1AvbheWCL0zJZRz9R/jbCMGRxyrSZaflbAsGnbVCVRYNP3aNZX53gfLVS6AEdpFixMvRP80DErZ7unsHNpoksJvSm6Q/ErhGreUaACCo3PY7TVkqpsi0DzV0r+3vM9Lo7eNF77+sMn0P0l1jNYGEjT03x5bHh/Fa5eSVAEYhhzujUAT8SR8UNEQCGMtV4WHp7kNSGRLaBDuB5YXMa4ydxuH3YtnQsR79EvxpABA1mFbCJXI3tp7aszKjfflzjYUjOCtMAekUtxhvda6/hTnAPt8+MDIxcKBPUVY1QsSOhGindeVJIFDfW3y44I7zOleUW9FINSlOdEVLmI0rLiOL4g7OeTD2Qu1TKczQrhivrseHmNWxs0Cbk95kwB3KH4Mu7MnKyS5VGAiMH7Bf5X8AyvcyU08Hkph7SSXO5IvXtqhjO68Rnd3RszChcRh2cPUeBMDZhOI6hlIpJapIXG3hdc53Ym20XX3Zjt7+CP24i1T8BumUYH6Mv5oLAwTzekppBVs1k07AvTls2TKOo0wZB9MSJXTem57UpfGn1mmpfCcw+VMh7Vn9uE53libPDFyuwNVHFffHiGutckGu5zZHO6Bs3Y2mdb3/knpd1jC+CL/M9j1oNORjfJ7CKOeQA/GefcSrz8PE0uLKklpJypxqlBrddHSo4bLBNq1yrmMxoey9RK5cDcc2iybGetT9Eyii9A9X6JWP7SqBHSM4Mz6kqHRCGXx+JHXZk6GCkYJ5yfjgjSH4h/mfXWQPU2JhbZFA1JzAZGb0ycVO/1m0hp/IFhw5mD7LBpcVNc8DG11Jet+R5u9zMDyvmZWALcoT2CqC2Y+isScMSZuLlNFlM7PMP5s/eBq3TKTtCMq8/RaxeyxUWCPmXMm/PrB5qxwcIzKxq3ERtc3kIrYjn0Xp0JaSA/O9QQXjRYneJ0tdhbU+kChfVLWDcCRvwWI2lkYYDTAeotPP/EvEKJJiD+AhhBybrlWNQcW03vVY331fJS7c6NmZAYuNkri7q8+zowfpXipdYROYlWPVxagmkUJ+HysWlyd9xWURvVK+MoEyb0Y4ma7plREyr7XuOjpN+4iCP6+0/F+AOwAhkxWt31du0H5eGiakujfvWhel1/pwaHbNiFd/QvV1YHvBYiaAxKpoonKBYuF74mtYsAlSV2+VkZjdxdJ4hayXg0FljL9ZQnLmKPERE2tmxyVPXY2GwRcdTFYEYYCGFtAgvW732rYRT0GYRx72hvon4=Question 7.10

/f8xNlIL0tRLVHYsQbuBc+bGoQUWFfrX1+h6Fxslh9y3XKwHtKLKvHXad15OfSz1OS+/0SxJwfqT40TXPUIMKUtwy4647n0lq7sL9xmepLdRmwtcNxH6FrsL0ZgQQiDmYD/OfarGduukAlUyV9a+4XaiyoYzC50fowoN3P094rTnfqSrOTTdaKeMZq4yLkzT/SD7IE94t/O70HGXTvYaG8oNZIX2O9Xpe/SqOLNTw72XWYE15jSovsg329whjKJCV8/g3Ax+1X/OwrhBixDZl86Jx/cVbTr3p5TvXLGMiX/95PWJ+zZwUUDJtIXw/VI4TCaRAK5ZBDd9p7Bzi2pe0X8wh6PX1XSpL8bQdtZxgXjOKLoTbHw0I3hOMggx9i6XyaQpIECR9/ueYF/lv7xhNcePwkxehiWs+p8S5RVgzA8Xjs7JBDElZ/ajZLGrT0rqB07w7dabx7RZIU5sPcL8FU7E8PQOAzs9QWk5kqAYrU/Fo2G1nV5QYbEuIOJya/llxc7Fe9nTcA8i0C/nbB1avEcrLY0wLT+vab862qAe9/H3gOJfRAi0Kh02aKYNxSRwk86JLYpJCDccU6vAGtEH/fSZ3DjG4f85rUMix6wtDAOJ6YfH3ePMt6bPnBrVa+Mpnr7HlkZ2flNduT7HydYAJ71EOhTXJQeZreFNt1pDhoTJ+2OhywRhOujUhprw+NwgU7k6FIaHr17zQsATz3r9tqlCi056fawkO+RmjJL3pH9noiH7WWWp4yt6rdKQU55YBeRcSoAg3Pps/KotWRSdhuosaPomqwF0xCz5G83X32beDJiOxlmaBH7X/w4Rb1w1AtBrwgg9nVmAi43XjBzwlUxUhMQLiGnaCNeASoaT+K0RLyGI9djIOVY5WivhtqZYizgr8yYGmAjUbzT/0+tnFGhdoFZQpVI0F0ETqntqPUb1BYoEVay0mDkIva4DL3cOvfHqxn2Y2TSFnkZGJh9AUs3rvgxq+EhWvk5bknS9tZhQY5WYVyB9rd8CI/X1CFbVwg/if+fwT5EFyTU0VY5DTmS98sIZfNnQZfygX7bPbhEQoAf+uF1y8icAjQEvWEhkVZcAdD+xP6K3XVnTo7ozQov5rjhP6vLpYtlCKpuPtDgkL/nU/YoWmAFvUeiWGdoWvysp1Sq4LlZXIzaohNWrWYejHIQF0ZOoBhJTDx+tGDimwSoQlR3GF3S/eyvHsP8r8AnR6GhMioeyqkRrfjmF76NkstSguqPQaT6bTFgyQGHkAS8CWNlGQXM6JGcoM9WYUbCPPdGtbTJNQXBk8B/W+w8UzP3nkleZgEEBYutiBozrLyT8x8A0v99wAZkwQ0ZPZk+b3eQdqJk3v87SPfxGjuGGb3s3Lsf9EBkElggX4UEjxzh/gHvU26BgNAKyW8skwy90Nyku9LnAk10mQ0V+IOaFo1mmsMeZUq5ztCCfpvsElotd+U1cjVxbYIpGVAOTnBXkgHCPaHaGu3lUO/Z5R7EA1OSaXy/9SmiQMpo6nvBisa0NT2O26LzvfQbPBJyyA4SluC3e74lVX6NKeA4aJzesJLjTDNItJgcQddbvSNKkYoJ9YNqo56DWj3gT7Qso3Dx2CeXDM4WcVURSoKFI6j1zp7DNZYPRSCh1WIHC2JVhAfRAnvoVUhaw/HFRCM1XjYsUFG+HW0Y/whr97hSxUi0DWoupv4qh3SDKYWEcjTBzGp86CFsrUwdhZ4n8dTU3gYLjWEnL5BRCUtfwSbFk+4iStdcUEYY92ryxi9ocH2D0Gm9p3U+wJRSDjLOlDp2C8SWyWkny3NSxWv8TubGijNdeJTI3hGvpufiKKVvktxmGFHdKqfn+7mIrKuccqDPy0+YaV1siR48v/9vrnWCbzJ1Fm3TS7bn2SwsZIRGu5iw0luUJVpGCMXLOwPPD1mYKiL8zhRQPCEeGiq5Qvj0gqqETWehte18EyBoO7Ubp/LEKGhjFnycVM8EtTCpW+1oqXAvsbre+L1mW0H/FGTq783T7U0zLTmBXjRuTwFJOmcOSs3aBE+79Bx3Bcmdke7CYSYfZ/lg0lfLJBESc4FogQ1U9RkPSfO6+HUzu0i6918L9I61MONF/HeTkQeHNIzSxypHSBtO1NKw5GIY/NtRdQq0yAPBUz59JSRdwF+AGLPn7bc5efndXk+u9VVvbZ7Rf9CXeDSZaPXkhKyLP+WAZtjfnvhGc4d/qS0Nw5vVri0IFfvCA610KPIpAb+aT8tB5ffDzaKV/sXmK7paqpjOi+5c2ROB/VgwPmfuCw6TYcmSF4LflATgLoRH/3E4XqBEuTmzz+n9gA6QnsppxG4Y26KijrnEAU+Ye/yhInNxydJBwBXAi2AsWRqcgtaz1NYZGowFTvBvbsmltePbaMj3RZTWVuasAWAFWlCBqzywC+gCeCxwpYtJM/bMrDPH5MtVshZCcH/+tOlptfJAywrUIWDpJsz8mxmY/l1UbPQKeyfSf0OYgdsBIOYaZtgqGipm54Mfa90lnVko2Sjbc++ZlgVHyUwvwhKjrUE4pf1X2yLj4gPvZ0gqfYavQr2104TB5msY6J0oLvJukVgvRoz2SNA4J6zA9Rn/gcMsdwhxvKoiFIWM4lxcpCfJLf4KsWg8E5Tb0wdhTvz2d1I+XibVoP3l4y+T7RTpVTM4NJ/lfHHmfsNs7Qg6Wsvvl90JCjyt+0QI4MC5jHooTPtHRr97CKUYgzw/8RJumx/0yXqcam+rYcJCWQndwOg==Question 7.11

IwAQb1VWwDOUDNHo/YQ/mGAzIRBk/oxFNU6fXrDHKK9gB94ZiHgXTs+T/KM0/8CitpRtvxXTR448nvJz7cmUzB2rrWHuZ0hE5ikFUs5sruNIULnVulQaGTLfuRZhwGzz6QsIKBkOMYCaw/y0OOKVa40EGIUD5ZWhdxdReC0DPptMa/ddJIYpdc8fqF5qF9NgeV+0yfv/zGQ+5qb1DfRScmfuMRx9USq29ZyEBZdEWM/td+81QHj2axc3abNybjER+2yqqzJgL72MxYR2s+sPliwsWICoBtPzVh/Lfbdiqv0VA7akrHalZEWrW4kXtVRfcgOzW5wns4rlircynkgKUinKHYNw3Y0wkfm9FZIJlHhTmy8R95yzth4phecqJ8vxp7jkUQPuAj7wpghd7VoqnqNXoxa/a+G/rdXaG8CTtEmVu7lALa1fIQgewD1VBC5hJUTt1/QVSmvsV+fq+jCpF2NHTBAXll/in3apXQy7VQOczC0zUK+djHYzItTFK/yIwZtp6TDrADMe6MzKKNdInWxOnqtfVCymaUft7DhVUmPIE4fn9HIWNjVFtyroiG0FjQlrr5J+jEBbghhr2BzXbZEuj7woomOgzLYJHRm88U0ZLHgTIVIlKNz0Rw3b1hNKKlVnXVkZwoHfu00QqGILBODQxSc7pPaRX97YGlTUyM4VmkM7QZsJzb3k2QH0Er+0q4NMdrvX7t5nOgTPxJUnUUiDBWE1QqTFaX9dhYt35N4JSQ9L90FsIQHTUiwXBeJQ8cBMrQHXdQ+/dhceE+Wx3hV5Y95PAS198isYW2i3XaPuWiWO4SMD4vF7iEriEPEv5cL7x/bK8fTXiX070ds7RAkvsEPAKhW+yMl5/ao4qS6CATreL2kWyKTtTm3rYgsC/58ZkQ1Dfuo2PDl4rxDhhA/nkiNgaVEFAfGB0lLVjTz4qG6hLhBm5y+/9kPqELRqJprZ9QldCWRKnZb+APtd3P0juGKhythTKR1ocQCw37Hz7jt+G053LtIdC7Ch2pra55zYEMQEdF2oMkW6OXCk4wUxZp66ZaTWd1CV+csG8UVu2Q1Fp/yBsf9m7qMNM7rjcdaUUvn9RXO1+UyWcTFtCd3YR0A7MIF+CLl4XLkzptZ/3tQiDjQ/WWLugdKhELvdU9ff7enStoakwiW/AxFVF7GMaeWSOwovtXet/j8RqZ8AsG/7RxUCLOW/B8eiyiNNX3TKqYNhwL3jqc5ughLnHouv/3jeN2deI8tbF+Z100TybPHo3QMqb+Jm+os0zqH9jhj0dwl8p/mwuId7aPtB/Cdu8dBG9gz41FXe0KlRNvAzm+kv7n97bvwluCITs82UG/yY20JQYPpG9Dd4i9982kfcUTHkfG8RCgQNuXuWSYCUJdq4zcs8SZeFwLwH5C0FEet9tOd6Ji0Wnp2Hl0ePXRRs6+7rjHwzTTb62cktUUlGyMWDy3UGK5bSUd+GWuHInmmjXbVvrtWKlhw0A4guP6NDcmtQ9J71u1kpZHpOxkgCHOWRXoQlaF1K33VRIMa9NS7xckB2sz44CSlJCjkX/33RDJqkXfHWdAeDtSUqmD4oFAWf8Vyu9doHn7AXvul2DhN2c4fCTgO74zQF6WkkIjQ4vtRJ+g1QPYJK30pydcNb4cF9cQ/Ta11wBrrJMYa6Xql/U+8iwjA70bZQqPb7TgdxA5UoBvRSZANDl7Vay8NusQjQJHQFhdaM3/CD6cg4/b/2wRJ1OlrT2YDR6IVdRSEOk/2qQg79NMPFQOa3+jUwXhjd/5AvtJBN6Ax+ckEKnMVGOmafEMsp3U1jcQKNc8DQ34BoV31k3xOYLpCj2HK7PraeMd8m3rdzyHp17XPlHDXN04ZaYaVAYShEuhF5x/TG9/pg/l5fSe53vZXw+s6GDizEIWqsWjyEFM6cACOYsCLyFb80emwOOj6310z/ZuGHu0dPQbUOcunEgwv8gBYeB/0c6UVkYubqXlnHwDz/DZdxD+svvmJgssu0xkn9jzKbfmVnm/6AbFH04RDFLGMxhMXN62IPYZtx67eMe6buluLJpv6QJSgBsooxvyaATD8DKON1AfGaUhhcKporXwoYZc7tQs9kldB5imCOnyW72Mu9aZ68LcTdC2D7SfFgXnaQBz7FbVTR5irE4WwWNLbxALM1v1MzaXBQ7vxJcom/y8Mr/zffiSb20uk73A5IiuX32cwz5zMMGfERhMgG67AH4x8vKzWt5ICHfkl2QXz2v5HJhM5pfRwrBLZOjCc0TNRysY4Rlw+VZMjk2vQDYohNIhdM1314/DSRSspc/ir6CJjYivyeBDoKApJkfu7jzDYmPUNeQQYuKMhKRkpgeFUmdk/QH4FaYzgFDSW1YxaUE60+j29MmL7rHNL9/2UCL8vW6leg53vxaHLQP2zW9qWqbyTdSfUJLjw8KShy9sgsZwIGpJXFR41IPFvnFWpZsnrYbgaZlGp9+7+3zO8/0J+DjhBk4hiYt0nR7hPzoAnrlsdnR/zhN1OpXevaIi/GZNJFZEXHxvRFLnG+v8QAY5AxgMPNNr/iM1DOF6nDyrA0vezbcM495r8D4AJ18YvCvyB0pYdjgrUtAzYtYxDNlc1+N8/8qoXThLfU4RygF5wbG9O5gqLgDi9dSByaa/ZwHlOm6W9kZ8GagwO3NnMdfNBKbfn2HOUYBcetR7TyM7IQvX/manYbSdqXuM3LX3SvZj2RNRv2yYvA6r/RCJeWJ2za0TiXwkzjnRXmGNfJwcYzmCHdqw8ca9OzGrviZWmacqLmPqXVLjNDWB+dC8x2gtquvUnNhUDnYJFFM6wt0D9ZMM94D4ogUsdcRAJTEle9qQ0voLAJFWDHCDcj/xmnfXFiN6uWhYLepNAhxIV7y75csPIs539wqwnBbyM5pPhp432Z9dvcwbmvtj6zfpsF53nSozMGmLw0iJVPt5EBGmT0sSmJPdgV/FpM94TzW/D7vYfjmbMfLF2e7uxY1CHm/uSqqNvpFl97aurV3E9P/Klv3oDjLopzuOTrkN1sEp1QUUxC3AQwyHvdTEd/ee/94M7lvSLopNb3XYiURFKfl1qv8Dar/8pL0EWu4OQE1UMbmb3rhg0gqivomYQ1y7a1WMr3YvV5Dq9B5RtNCUjnqrngEc/93MKTnpGmpEfQPXrpkAJZ6Tpbpe0GNe3yOUahj9IpaUNWiTDKaCeng2bSTwzU/WY9Z60rhhqc5x+I357IrQVzABTkkKYuecZqP+uSbTfv9a+q4P22DQfUs9mS91yP+LzKTxp2lqyZ6XbBrry7Cj7hmr/yV0vMRclCHUXUwLqmsxwRcHIut8Gyc43qejJfSPDSaWUDfA1sk2DvYx87Q8tUxjhVrEwSDiXnRDnIL6ktsiobNPUB0+zT9/o/Uw1q/OBor/4OljdyZKf9l6r8nKSB3slHiMtmooMCbs4bBHWao3spVTJX9ORkffzfnIhdBTt1KEFs84wntC9SzqcPiToZN04XJW6koeLHRMbxU0fPSef76QEYm/AhgVF+gpihfgyfEexRpcsv/2lhStDUgUR9FXOAsUlnNxa15Xme3b1H3qV841S3kfhxB3nZQi5gNUVgYJizysYVJsfJabrQmxbNGAObK9MH+VBChTmj2Hi02Ju6iDOmONsAKNtFEWFSnjWzjI4h4ync0I5mnUvuPF7R+SRNyK7XXO4bwyQv197SQKbW3vt8rt/4+BSCUr4P2HRMlfkffm7nrCPuwbdz2T8+thJ0MfBfZryRM2UsKz+nr7RxpfCD4fSbthXx9vfAVpaDexqMNqJuZEE2ppXK8s8hGSjb1xwqjcucxNrE9qYABCw3wO5U3VvUAEo89HunI7X9ZzrGw2bNrGwhS7WUdLgfkNRxs1raVpxq1FdMw43hb1dIo+GoUAqUkuZNDW6N6gz1ch6kqQgZO0bZv4L3xBt1wskP96PUh1xQTuF1c4RiQrENr1Ph+KIP94WOm35jUftr1WwagUXORgT4S/Y4u3iK2qop0NKUCLzTVRIwKBAF8W0RFT6hIpjY7FOqO6twKBxkA1OrZKVkzsTLFwS/8G/98T8zuULEUv2JR2x5oNAB8KAKZ90kZlakb7DeG3hPhIFBGvqPT8+qq7VR+RzpRZg7vpAnDkcGE/WM802sN/xQ1ccdwPbwcO4ZlJWd7SjmJUn4nszsKJjNLFsUxjMrZjuWnWemsfzVErfyTSfP6fYJeCnz/su/ETeO7XtCFva6JmCQt4qwu26eYd6gP3vodANfo3fg5Y9nD+dMWeBekq/19mITGwXZmvkwIY5WFpV5S7sU5qxFpw1Dg/KQpL7mEPmNNY2DTJizTuQdqfLBNHKH1h7s5k4mabwNOXBfjvLXnDwFm0BZEoY9C3ZwfEkit8mKDXaKG/haBph8grBQQ43RVZBOVrj08S/fA5lw4aZPaqkXFoVgRKPWgZOc5CEiWcwx6sgUHdb4D7EntuXeBmatAC1S/knf23kLTl8gdB9GkGohSTyeNr1ywuKHI8SdKhFJJYT/fqTjNB47zh18cFFU3UTHF1dQrPMGeXQ9yvSttww7I1fToY7reEPfVkgxLitlUAv2C4l+MLWPo4XQSkC/6INCGuW/6A82NEIGZnKQ0EXNAaZEfrQq/x15WZ0mwAvgzMSbpJUeIohmzK9UMJddU6azNLvekGBmiPsmGbOoTpXfuHvF1y4CGFOwKwrjzakYqLMnoNMmz/6uxRc0FcK/94of84TNTBKBs16z+N0TVycbpKbf5KMlYN0LBi69EoGw8Z2Su/psWGC2dnjPqcTBbXbXcIVBIQaniEyCKQm2lcEcty0bd7S+UpytUG8LKZ1WgjWGSWAygrC/er2EzAmupTENr+yxdMz3sn9TMy2jg+Gpn5P+yVg1O+yzF3y0JeUvgFOuGMGoKjVbacKaPKXB9eOz76D4J+o+V6MjrfOthVXCRMM3LfA2ktU7xOXzyf4RUZ3zEN/lmPpQ/WVRZ9GwM75n3glyAuKcRjomaFTfPJEwbtJKpjejQHtEXU6E6DH4bgrL81VSrksjrKWTj5M7MYERrheakDTMVwTNdv4ScroWyhbEhlsOCOnakZ7KApvJlJ/7CZtTsWj3x4435cQTZgfbBWfFVkKBqP9643Jy3R9eydwzZoO0sFM1B2ffk0q8E+RsO+LwGORn+tDhtLIBJB/SkloEZh8/Bt8+ugOLdiZCp2vBVBeU3Zf9U9krefiF94HkeIN9YXZ9mGN/icCmUa1P32JJo+GW9nU6zPqgFPhOin0avxknTwtjApzb+eNNyXNDRb0wuGg7DICPxJJmqkKsa6DB6l7GvfHy1gw0Pjtkiy9yU+8y3ahvPJBoag8pvDLXPLOWsrmL9lRKUr5gfV2zwWDCFsKbTHgnOf4e5hptuPmCWkJQtq8FWm6v7daLJDY3BfMvW1aVL/e7Nt1q93aSISf+NFLSyO95ez8+t0pbo6EZBpgO6BzdCrA6F7jpUArEbnPBCeXD4vQJ+fkCyNPggWFVf9o1RSvvtODcBSEC6wekkxzEKrQ+hgL2cELoZfpHCWhkkcsMKgl3tOo=Question 7.12

QT/exSrk7v3fpZCtaaG5sA9VXXQira2i4sLugoCKkO/zCMjSeLePGQqhe88+PA6JqUhK9/ptrQQlAzHuzHk8FW3CqnTfsQ2fdT+oVkXgHj7oVYyVB/bxSmAOaEL/nRtSKdik68keUF0IMn2/P/rmi94XpCkJBKyiQIPYGZ6D89EBvC4e6zTsNLYXftOtQ5kn2qc/NqNQmjNbVYbY2ndPjxRdmOlNNs4J6aMh1b7uD//+cKHUhu22wcpGPRlKKLwmgSrlLB5DrOkjUg7yxgol+6gH7+4mVodMHPal/On8zJVHut8B+3jg9W1Mhk+9P9NYyZKXGMHRX/yNLXi1Yj85+YJiuL3fTjs03smbt2rU4D2aJlGKhWVjPglby6z2lzO/a+NF2i9gab0q2xXD+j85I6JRCMlZZLXgdjU5h9FYqqJYhAY6bFTDRNWUJg8HgkOZgAPuOW6ABOKxCfOO6H0TEcfpI21YVwTqyNt+amvdUFmdtN1ujIwaI0HJaAEbS9aNy+4/rt9j4anXK3WtY9lToJOxJbSpdL7nXkPo70WgYPmIlZktIKneo62wgIMoENZhNqNHPHtMbYPaywWgPqMJXQRBIzdHGx4d/7TTHljaV25QcaiqG/AL2CDZF9sE+7NKf6vtGkOCXbUiefhNNJNSabze4cCUVDNUfvLqsBhlPoIeKkcoL+GE1QI64Q9o+4AFJ3+O7MQ8kugi7uB5dAOitLwJWbq+sV9thchEz3+HOTtiCU5K1G8vq+2hqvmIjIKtRvB2RMFLoRPbOx+Q1mTJHreFmJ0d8pySV3c7PmJx9TwIHb6yYPW0e0L2Ipm37sU2ZQL3AbSVPwmSdrXrW6OjdKmRmkEJdRe1wh9PvcTFmu4ypQfhon484jF/UrA2AO+tbND7ziiOcwWUKxfZNwN2tFVVCb1z+ySKP1gdELiDllFj3GUP8vJeQd8Ud6b1jLX3AKqa3J7x+Jkp6z9Ixy4LEb60pOqHF/qVQphPvYn3gc1KBjNAbur35VrQB8hovHxlyqwE2L/FxKopXVHTBOto3dy1K0kFd6vuKUVAwu7ICezhpybe6+zXZulMO6p9OZzAwzStahgfb9Pm+oMGa3a3TSlJIdUP5GVTRmMpOhNElknOnaJk4f1UjJWf2jjZHkEevd9lTgmoa7fs5M4UH09nB9apQYuOmfyePB1pXLBs2swgnhAagt5In8Hq/k23qKTmP4RJLBbyLt3UYmoEOr0KvahBjd7wFIRnjJCZKY/dYzIEIJgn8OrLYcntAWcYc+NZ9QUGo3ay6BbVms+Mvd5rInzLQpDjnlP1IBoUn6CFYR8qAMgO4mhCCkVvK4zLnL6/21YPOm3ThCwDgpXq9ifInEeAVT8LqafVOHU/mrEx7FBntBeJVPIF13tXViTPaL7Fo5Vv/zu/N2bnHO5o5FnwnThegbE1JRjEzARQ0Z26SsJfwfwz0Tjc32Ah1CNjpg4708bqflhL9Gb/5xPmfir8wCc7Dxh1XwC037qbKa0fdLyVVhG4yiwEhDrD5gQPNJGC3YxAJimGhpjetIuxsEgN4NrNuLoGpAWRXRIBeOcXDm3f1jwb6KMOxmDxmHRlzXJW7BSJmQKZMZOe9u7vW9RTxh35Y2wgtuIIGrPIjYIO6UOKs0kjpgs2NJ3pVnmaC3+NC78HH/IRzfynaactr613x6vpQ2qHvse2F2qIMlEUsFnttKQ1DjrBlb1fymL9BxfGG18oRsycBvQnbJXUy+xIqAtGiKU8C6lavNW/iVK/SgHZLXZq3vAe+dHBfQrnHL2eFAol5RWukILcGt7BpfpdxbFaAAsOtxpIAlZ7epIgnRmgDqf2SeQYuh6re6pFmHdvw7fgbaL0EdR0PBAPZRZMGUG4roD3E8vBY0Nxo/oN1BfAjDLwPS1TqtLNfWM7DBLE0jSU9CAIZbEgjVNWxdomp6ekr0rCXH/AMWjQUFfHsEEzFPmtdn1vkvjLLEXjDd5OwCuuG0GSseub1xvw/mv1W2DnJZ7WpOXue6hGPJ1E2uo7BHQQkYZRAA66vnvkE3oWcyczP5utG+Dlj+NMJ1g5g7G+jDH+AytJSzIe8DlwBw3QCUMSbB1g59lVEOOQGb8Lj86HtNmNruphEc1ny60hLQA0tas46PaqCKecdLAOAIAoykcKPDyIp3oLAqmFrsjwfIyK+808SefLZL70mjGNLnVPxL081ZmT4/VvKpVp9HrlDj/ySFkOY+Yp8BnYKmT1uenytzHb+5Rpsq4J3QB1NPF2ujzttOlakN3T8aJDWZjhc135PWUGkhOh7t45mVnk3rGYDeIPHXNdvtBRqeftgFam2JZ1SPtnq26vrKvhFK4e6W7wzdyTibAnh7yaKn2snhHciCIshdxvNOi8jPHTpMHnZLdah+Q86cI8eBGKuDWPaR5g8GFjs8Ef4w0sjQbfFBSKrpcdpCNCKHciOyhGJDNKzpIPiPgY+x+dyPvF2TGG6vJmt1ozjkd/7LdrodrwCl7r1PhaiUyRFIuP4+TGV6Jlvda+Sl3RwrQ1ADheeF5oSxLd1eOFXARNR8IvaG/Qri5b6jtxjRylt6FpSaTFmP7/OkWDnAQPe14APJH4hQOncUjosQL2+2/KdOA3ttpawd31PSgA8PQ2JKt5Gw3mk2ExIQLwGW1b7n6LFjgcXLHL52xFnzTWVArx8phyRJ+8zi7FlERPaCYrS/keUQ1YrRa8i/TKgVb38yszitbFao41WBPlb/56EyCEPUZ+I42OVk85HJNnTIJoCRnY0pLYzO5gptnkKvlYAMydGaUAi9snw7DFtDHXe5kuSfw+zT9EYVHP37sumWnBBdlAT+l17xcL03gSpgKdyoLxPJbZqQv54UOPPcGFldtMjWq8o7uizjMsRm6K+AZtzzikffrOPQwLKdGCL+4CEv5eD4v8nITetFYg+fCGNTHeqPEXiA9YdIBd+cf6CTwj97U55ryTa6df+Jq+KdLmPwsJBPF8it53SCCZ9ohZcf55UgJL93Smx9xuOfvptDXsmB9oNi0HM+5ip3+A4k1Xp5vEFdGHPouq9kKjWz6OveYureFvfaBJBvv4neJP70aYQ3hJi4pOO6wXTRwI1OOVISRyzBmzodJTvLlNR1s5qjGQe1LmNG7nfotY+Fl2QkEZH2exqgiQgj/loOU3fo+iZb/Q9xQ+2J3g005BXIZipto5LROzRA5rAIl5LEENAImg39c3oe0KoGgzWdXdfQQrWsZlEBfXK6sc7vSFxQznECx8+I7vQ9lVXsmmiW8D/5ZQGsP9PfOcwetwi37pXgaWluEvbkzBnytBvkTDTnkxS13yZ7mQxRX/bs4cTcBGF1jG5hBqMsUyXvzMw0MrlWaLRTHwWM3EukRBoNo9/BakaEpv/NlJjIN58BmXiiYWkmx1VwpWNpvspwK4PNnXZ/dG3jyS65O+kLbAsacI3pB7MN31m5aNIppWtrv1bx/GUn5KpaDEK7jvSx5GyucocajpzT39yA1a9BJ/bWDSGgk8+fFIsEdNB2vVd8PnkSNdd/LXZ9L26yK6ki8K6hmuVQkMXvOjfczWNpJIk6aI8Z7gh5358ZU38vkcm46ji65qFEBNZJ0nV03r1yKg+AfVa8VIbxhnKIj8KmnU6P8o/THd6DYI2CoBarsGdSpph2K2gYFijn0xDuPwzEcP7My5/EkhvXQDytZICjdvvqRSPf1ItHM8Gz9TJnPJAXdksqOlmUUs9V0m5aJv1kMMA0kdzvntSDTBA51jWyQqe+nCOuV23IEFP+qMsMbr5fIh69/gLyXlTqiwewcyoBvL8mxoHoCn7ngTplHZXRU+Fy5euxr8kR+Ly1PjIKsdCvB2CjnOXV/m2KRKyeYzlqUKyifICDPB/7ALAXCNaz4teskR1HZf2hFtNYnnXq6WIhi9yH+eM4iXmAcKRlGOOIgucKq0PFIbvRKuZE1ioqnrk1ckeegB/MbmnZF3vJsuJu4WP1bNzcm0uyGze1hTA8733ySUBd539sDZ7jZTYt/dCOIKkcw37qMERjHle1CgdR6WEB8P7vY7JUDpK8/GYNSOw7suW8fJ2k9cM9qGvteZHuS4X33wLBsWyu1vIWuk5Ic5RJHlnnJctISfY++wbZKMtQoqC8JozmWjkmvnulxV65Lt3GVrq9jRVTgcBYMVXUaIEnEIcf+RyOxZIFDrs3dJTc2y8Bo0tJtdRyVH2aKTEsyfg876W63pQ1S805Yk0yvIV2SkiQ7b/sVaLxiECbNgpcXrpFKfuxdnu8GF5zOCa0oRSYeUykB9deDwrPtvLnmldWqxarvlIUqD+S2/Fr6icGoee7tAV7r1pnX4Qv3FaylOb9QSqDXcbzMVNX6T/Jau6zWxQuoT/wCg0ver68gV1ajxmdok0XylKHIUsdScTK8YQab8iWhmV1QWAjOnSYHsGoTI2qFVZ7u8rsF/p6XZZPC8C2rWxpGHTDsvq9Dv+g65KX6oY5ZRmQtdJ+AfMdHUDYjDM/EeDAHKXUrwq2WxmlkVgNyyq/JjULJNsSlmvqQBvNo4veV75Hppyn7UOo9o/AaVs0MvFVEOjprNxnfzVqA5pgeAGYVie6mxfvgYO482iUicKHAiNBGdgGA+2ZQdFZSRIrNudjobnsvhQweBnLWY0MD75Xjb79rtb44kBHYn+2YIKO9geuSSIL7h6GUGC0hlO8DAo3APK/Mx450pohtxabf4/y11sDfMZ/+ngWJBlQkOFWJSKiFoYc1Tr26bHH/A4CaEJz45XKTz2RdrKjdHQXpsD1N4nlMV1ogVULWwoG2t+EaEelLgFiSYIqXPgvB4zJAuB5x8UfQAdnkIHH9ri9hpxLhf5h5UXHVCnnkpME6MeAXiL8U73kqvzezNuT5+vnQzVaPEzItaD6XIRPWd4jcZToB3lDLOuKWo0qd7Xyz3QSbg6smcnSeHzhG/L1h7gN6Vi8tEvOzFFnBH7yhZY9dx2ib2dV6Gk7qbiFTKuDAO14j1tBhoP4vuX5/2YDVIykvKNPeC0mbaXnGUjuTjnGHqhxgyfgjIN9TdTKPrXbkidTwlJHorn7PrDt4KZ5ZGQMzW4lNejN1NYUdruo1Injh8FQsIVmOCsr4K6VHbhbTizQh/0gquIyLzndNaCue7qN9cGOzrQvWQuMjnDR2RBXxkRudpStM51uiw+1Z8Tj/xhDmsRsf/RF8RObvSRBovk7EJm3h4c+7/O4k1lbxjlrsBGs9VuVKkRJTKjE9M63FWz9hqKbMKXO0B+M6WflVrSmvFInvSebDDPiYImWfgUCnImhl6ZMcXJHAUbTMdAnhiMqbf9hszHR2G6L9e9I+GA1NJVd368zcpLlEjqoJOspveP4GIUptfCmJrIJJUabIjZclwSLrJcTJGwKC5KgDpnJszIj9gXCbTPxg5wJrsRfnhVbcPuwy3VXUUmX2OAJOSvsPBSis+xXK+CnSDqrvemMnVZs1Z3fgi2d3ENWv4GptbJzkSAn8x4p0alS7p9si/rKTFO2GjD+gtjtOVx6DiF3Pw8BdXHDe3NjAWQRFXpH6xh+lzGzxPTq/nallb5hN7nqXPGQc5KUbgg5lXsuJS+8SrVwTX2A/CsZO4/UIgknhNtShtKQrs623urzc1CmCtUV3UktdTwqqxeOIyty/O7GJFMQ1qTm4XTI+9iNViTECXfAxUcgqZ80l8s+XIQxQ/cGCV9a9dxrJJYBCGhhC5pksqfLOp5lGm1e/XM0VYJKdSIXQWYfcmh+a5+jt98fGFeoLlceteUzCX

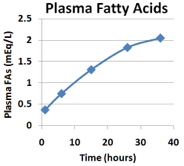

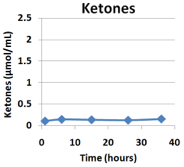

Conduct a fasting metabolism study to monitor subject’s FFAs and ketone bodies in response to fasting

Results: A 40-hr fasting study was performed. Refer to the figure below to see how Jessie’s blood FFAs, and acetoacetate and γ-hydroxybutyrate levels changed during the fasting study. (Note that at the beginning of the study, she had just eaten!)

The physician who oversaw the study noted two things that were abnormal compared to a normal person who participates in the same fasting study:

1. Healthy individuals produce significant levels of ketone bodies by the end of the 36-hour fast whereas Jessie produced barely any.

2. The study was abruptly halted after only 36 hours because Jessie fainted again! Fasting for 36 hours is clearly not safe for Jessie! Depending on what other investigations you have already conducted, it may or may not be clear why Jessie would faint during this study but her glucose levels are something that would be important to investigate if you have not already…

Question 7.13

+Qrtdp+7qviDi0axXBaYEkQGZm1gVJ58YyA8fwBzH/8be2Gk/w9gbqY8XtindXKUw6etZ4ZdBynuuLD+VoH42qRJKmGwqlSgLdfax5H+uL827e6LpPkXkC52TF6umBsNTvD6MjQvzptHIdUt0FiLQpwuDO9uW3mS2MK6vbL/t1tR0YWfXZY45e57BhNIbxYe+w+pUDU0648pn57z3VQXF5gPeFOYkQdvs7Sryrr4H4MdTWqHIsZSUpVXT13dvdqj7gRUQwXQA2kmM3cSbBws+io7dV0c25kjWj+L19e6wzfqVXNV8/JwF6zlmBBvA1UZcanekYckHOt/iYXrNI6VYsC3S5CCqqg+b0BQpYQmzF2YHujjRwRzqcy5sX7cquffcBrceqKngutHJnhm9lEa2WogyvYlgy3qxRANMk2WHa9m10H9Wq0Fvifd3sqEY5Y+zsYaQUk8T8sWnqN20d2zVPKayVHZv17aPC2O28gYYHyfBMW3vC3tyYBVvEM7SoEb5fmnrmUA9hES2DOfZhoBIon9KlzRM8rBRTQYxlH8M/GUyeFZpy8t+WinVojf293zGk7B+CwQ6GuTyZVgYGi8ODTGgRruZdf8JzqL0tZMMDsdHId9gkQflm/Yu+T6DmhVOTxuTQsoVtqnOcu3+cndifekLhPYi5+WpPHqNhD8eAS0/acyMaIgobvLxIzVUW4WZ/LOIg+Sx6lDDbjFvzC1loMhim5rDkhj+Xu51aKBKbwJnHuWZk+m2rRGP3ZeARm26TiTF+v8rogs3q0ZyJFlMv/akl+9DmXy+0v5S/c2302R8XnT6zQgN4AHo+IaDMHuSlmMe5X6jzfmPiLij/uo+9Mvfp+TSc4EfkYzy84fkw6TtIjLboWq3GF703Sx9UDzP8G60U2+/k7Ueg8r5oz6ZdWU2O7wFxBEK/Akj1J/t654H4lJbemZ9nnqITvfwlPq0LjZbE3tSBd8ZArkGZWcZmtykH2vS1vsbwxymp4QX0wAAiCwyqDDGpfGsbKDBNwsAGFNhFgPOJzGVvYbuK/bcm5tQ67oOySo95z2EqoZFGQEkBm0aZ0f0r6066o2WbJk3TjDNmfnTlKY6s/aSTDzVaKq2Kg/A5///2VqUlWp87RDkiFailGPqf+i7zffc0B0vCHDKeFCtN/OKz5PRK0cD0ZJq6/p1f/1azfjvE6fkHLefa9LTrKC7BHLrb0yHaihYXNAG75BaSVry8vstdbUv0eT9quga22JDCGvSEH/oTFbJJuFPVCUbn5S3i0Z/VyLUUEc32xckWByqOcs767RzNxNMep88/2BwUdnHpkPak/rBsy1YLDbBl00m7hF8ZHDk2ZHLrDhYllL+MzSs3GPnANS0QYE1rIkQjjdbcDyfLYnebO93TgvBPBtyKw=Question 7.14

ePhTkDyuWaSwre1eomoTeDF+yDPBeOJGvEpZWJPn1mmCfOAuBAATORFM2mx7YYgIAyLiXABPZptFaKHaTp0u9hsUrI6WsPm8/CW9mLmWkyMubpgH5/Nb3b3ePxZV53MJpvy8/+FMmi9jnJAfWDnHZ1zgGOw2OJGR/oc3WFBtVhC3a4B1iGfVHGZiJ0fkNPXvicQUAGYIdUqOAfS62r3hfBvoIz4IOC3TeInV06CQ2OPddWEmvOM2E7aypFYwVtsRfajpiTzWU0VqseFOO2KBEFnn0mDOHS9Kl+FIRncmNwkJEbHLh0S1m7SWqOmfJSPXIwnl2eHpEIOS2CLeEzKXqzwYNzJpzExE/qF6u0wbxKD2mPGqlj1D6rMItajWGEtKyeifWH3qLgFzdv/quAgavEpGlsGxYy5KqxY2ZMlOdhKFTXdzwDWidzP7YfTJm5kWx55I2BbppxM17SEHRp1V+EfSm1oVe+geyhxROKJlqobPFwjDOFttC0auabEf4a5Y0muDPN2pzLZMS32if98WwvBHc7n0bsbUEXEZfNCggX8EXdrBtor2NwD4v8yB7C7gDm+joLjR9YRsqX0oajX400BnNE/fLETGCxjkkkvscY6vktY7BkUsqyqt+20u4hGwFFslTYO68ppTssAdII2ucEhWAi5dboHiijPv79C3LaI4e4t2CxzgpyjJpLLf9xNva23nQhKKsmI3qd3sDcv/yRA18h2hblQnYDlQSVLYGZzixSTTAKSg/S5VYYOxJRqw+nkaguyn6XkgJTVigwlsIxAJ0nS97P7sk2UeMLC1HQTtWbH9PaL7Z11xSmVYMuAc3nMdN6AWaaXXRWM4Frlg3T8tBcKbjWdp+G94QQhcO+Af0MUmK0fPLCFidyH+eTvStHmHEEFLa789Ft2q40R06U1V81qK33oA54iZTZOPujr6znupVW6bTSK4XcDOqbtc29clGrlLa4MvIQCK7YINKz6LnJECuNWIUc43H9OvZdBHOrl/svaHcJCmJWXWT+1bSB0eUchWFQ7qV/ULhQudYg2jYlvjCkVZCqj4hNxMML3xL9coeRosbcWkaYRtcZIK

There are multiple possible explanations for how and why β-oxidation might be blocked. Consider that there could be an inborn error in metabolism (a polymorphism in a gene coding for an enzyme in the pathway), a vitamin deficiency leading to the lack of enzyme action, or a problem with the transport of fatty acids into the mitochondria among other possibilities. You call your biochemistry professor up to ask for any ideas about how to proceed and she/he suggests that you consider looking at whether Jessie can metabolize short-chain fatty acids (12 or fewer carbons). When you ask why, your professor tells you that short-chain fatty acids do not require the carnitine shuttle to enter the mitochondria and undergo β-oxidation. The fatty acid chains in TAGs and phospholipids are generally 14 carbons long or longer. Since the majority of dietary lipids come from TAGs and phospholipids of other organisms, short-chain fatty acids are neither prevalent in the human diet (with a few exceptions like coconuts!) nor are they produced by lipolysis of TAGs stored within the body. As such, the lipid metabolism we have studied in Jessie’s body has been primarily long-chain fatty acid metabolism. Because short-chain fatty acids do not require special transport, it might be informative to see how Jessie’s body responds to short-chain fatty acids. You have opened up a new investigation option!

Investigate short-chain (12 carbons or less) fatty acid metabolism: Monitor ketone body formation in the blood

Results: Interestingly, when Jessie was fed a solution containing short-chain fatty acids and again fasted, plasma acetoacetate and γ-hydroxybutyrate concentrations increased.

Question 7.15

FpTyd4QuwtZU/llpsnBt9rkZQ6Eeqg1xSpcyYkUzb0zRQPueBQb7dEOvaByTcB/bl9CZB7PZ53S6OhiaiB6fEmiHElzipZk0VWxJydQqksBVgewFac8iATOE/29TIYcNX1AOVpSbui7WoYnm50G+8xlnae48+hZsM4U65Ysw1Q4/Yqk2Yto61pB7cc9OSt3HcPiLARE17cPxClMH2sxsH3EyoGCUfFDi5HTweTNo0XPrQW4Kqgme6wy9U3uUyPuluQPBJ2dr2jKngnsvnRRFR+GJszaQ9gfreZTSBbWfIb9zy0NVuFgR9b4IqfEemqdWGJk6qSc/fZ80x5PhW43QIvBHmCH5Jav2cbVIoTmAr1EFLhjnwAS+kxfvm6sSnry5X5aoiqgt0G+v349oeErNjaPQ4K9p4bKpYEhYDq9IHwdjQBEWdCacwCw28UN1eyzIgHNylhfmCgrvvbJEdfVg9R64kxWiHDD3U3rmQz2HcjMV2DqkoApy6Eb5FE5WBhWSyslviC5UAbCo6AlAtKR+uAdE8EbYqdP1O8Z0aFEIXXY7YaOULDHKdXKFMza55ysFDGSmWDQ9MvrAuVjjJDwH/5OxdborpK3Oi5fL3z5SvZGpicX3uadk5tZbFtrLZM0GStHi+k5BfgvAjKNoCmHl6kk7Frq+ab5VwAjg9MVldzAQ5iKr8bVBVo9fd1KH7HbNcJEIVJiBm17yoIcKCDFHhQM4nq6n9tmRm1VM/87rwKP8IYK1L/UljmdCQonec+Y2q8xVAuMdY19gOQUSR4Impx0qaMwWaaA01KG19ch3VjQ0tKOTcWp99GebXgyxggYBBHet2g==Question 7.16

ojETNi34tEwfPEfheSLCVpo/gsX51UZFX0RxXVqTF3wYDieS7nGRIBYa2HEb3t9c2ZU6A7M51p6CWr3sNnQf0XLcRZNwsvrUwR9wOOR6yfk3+srBA+rUsv5broJkpoOvdT7H8NEv0QzW3oZaOqGCOUaCzaH6vtiSZz8g60CAovSyg9V+uDY9LcBtBI3oVpbioTVuydm9oSe2EntZE4wxmJ9fWOgL5EBtGE5Ff2zxYHtGHWix2mNG6vQzYPibGR0e72Hs3osfm+6dVktg6xIFZqXQpC79KU/5cxs3/Qf65SYctueTeJXWLOzNFkphfubCDe9XY9awsTOO4tWNJV97h6MGVRPjIg2DDjxF3PfNtJZk8FVr4i91xbQMo4OgKgPn5VjicIIYKRoSvpxiowrx7yw/gag2v1o+4JJMGCukS0cT+FxrKR67MZ5Er5N6mfIE6ICPOWBrxMdt9/YrS1GPoETG+YVS/2bNpMj1Vc/Kh9KEjEmBKcm1e+SfVcHuiSN101wIPBJZlBruPAtkBbiGh78XxqAfSE+6u9Ka1FNLnxmLph6JMTDkBABu3CPxVmIB18kNQBeP3Ta7aBE0tUf3Kr8hjgUtcU9BaTzfCjZxz6rwCCw1wZdRSMZsvuD9AeNjIsULqf8ZHzxKMzX63j8EmFS7KMlWMH+btbQob7RPn4xbjWdDs82Y3YSz7l/1bvIK2Fi93ECdMT32mq2ftXAfg0p2w9n0KWjHpD6BkltHsEhIdrb5/ieLLidUQusiwXWkxlRLRTGy6Owfl2t7IkCq0iSlXliD1BBiuo6WreUL2o8hd2sTAI9lFmgygSr8k8q/g5qGptEulu7pdr0ywEeUs/AUjs9WI+fIe6h2Nz4DsyPGukFAIA7VcvmDfPDS9jUgpJxHO1VUFLkVcr9ngSbJeynvNpz+6o3oarQP4ga4LWAHuk5njcajlUB7aKSIxnOFLefJUoPJUgYpmsWbu+W0VtmrlYR3eEbZQz42FXX9rtzm71t0CzdlR/BrtfsrWIJ3bz70wUuqyeUcDrsyEpSwiuLmF7E8umJd88b6BAekFUFlBBS0eEzfR2UBjVwq6HRcmmC3n7xSnGpAvEmRip25Hou6H9k7M9kojPHu+76WpxiejjtGfDIZHbQFArDnrIkq+oP/v/FS4O0=

Conduct an MRI to determine liver fat levels.

Results: Concentrations of liver fat were found to be 12%. (normal range = 3-5.5%)

Question 7.17

zYvubXwKJqjdU0uW5HYtrTuzWqP086YNbP/ufYyy1hVO4acLrL2t7e5C5oY55wO8fVJfh0vZv83u5naIaTq0tFPJTKZU0VElMskULTCcFTnnP6Xwcprr7IHeszxPmgqm7tSSZZBVi+H5x4URasyTJZFKUR3k2VdLV655SG2T5i2NKS2vysp+KgZorBGnGopJmXeb8hM3HrOfOYR9VEF5TRVDdMi6cNK+tWW1gjVYID9qH55mRnQgbiN1satnamIITOyaZk8XeC3s5P/HfVw1GV+z/doLxt0rtTv1836WhQDTnaOSy+Sz1lnm9rV4OxCi1pT+Z1FofE/pO07o4pgQavAB87k19SWZiV9nyjocEt0RW2zlCrW1dTeFOuUwGA/iMCaQD0Wi20qs7kuHdV7aqhbaTxJ1wdiGoeS+mPgdSZyuunEwUCXK+rkBUv5vVU++DW4mprmbkgDpAyZ+CgYbJPFmLs4/rL/wXgG3tJLE93/5kcFh+3Gmga8sask4k6KoPTdeotsfE8WPUGp5pQ+IvoQNkNYHAwPl+OCi2Fy4u8pciSwO8PPoCCA/JbbuFjGdC/dn6tk4qay8Pjh9jLpvx9QWSmXS+k0K0WnR8aAuyScsfRkQfvAIw0o2gv/f3GYREibvZ96L15N6PXVbZIAdTvprWWFrmMggUvXe/YRAdwwbm+zwhsyVUdE23dITvz0+Wyg1OM9GqW+69m6aybiCalEbhWtnbIdZIZFKhGL8d9cc2O4cyCm5WNPzMC1RoHt6/9leCvKXM7G8uiDNZSJmJ3j0a3JpUSwBg5Q08vDuIO1Z2QlzhD7Jh1n8KPYTtH2ygjyefCbiZMbGCR9EwEZBYKk686CNcgmDKxzEUv5RhnUa40c8gjNsSHBaxmjzMBopPLX+VnhhgerA/wzhiwAF2bd5YLJZWBPwAj6eeKiPpVsGcOutx8IfIe4eSi5T62j43Pqri9IMv5PO8RgmC4nE62e4+2u22eHHlDYTlkHV6K0JHf1ZOO0teaA9NZAJbaMiGP/O8NcsNcyB/sJBC/+TyZsFoSXm38bq4hwOwdDvZu4dJqAsFnjOojvDp34qtAOhM14HGqZFa9+mfGdGmZgITg3HJgcefN4/5u+aX6m6XFq8cLEDDvSngzuh3Za8lknF5/HeBTyrDXJHSbuuViEGzC6ov847OeyNiDRDUvm1LpBVCG30Q7lOl7XvgjlBHdnFZ1rPXV2nStbVMvEZR4znfPlvaZIKQJ/92YDK6uw4cipv0r9E/CfOnmFrjybDanDlpiHIIxAXu3gI4e1ueQmKYwjKDob0uBEtpD4YMqmlC4eGk3565FpCjCpqZSnCml9XHS6Dopu3/W7Lf4ElZeEFlM+Wv/jNb9igN0gNQKH79obaqfouv9iBesD/qZ0BahYj+4fZ5S/rv8ZVFKal3JpHwXZsyfjloH1reoaZ2k+mP3z4ssUtTbMTwOvnYsyimHoTQatWexsbV/mZmQlrzXgN5BkGmZszpLJ6vEmJwL9/mlzjVxRPTk3zF94KbnoZ1GVwxPYI8wfy2zpSERiclGjG7jpMuxS18K7/jlR2jC6+wW1gs/Rrz4aftr+2xIiXoCqA40sprQJOzV3sB5YM1vweGE+F06FYtqrfklyfKnWhmxy7Yrr0CCB8KEszNgdAfN9Uo7Ek9vL5YPNBuwvxXtOUv5u/b/IaMIozasKZe6gpWd1FyTmewZb7dI+zQY7DHWOn4ydiDWQgU+C+qhKKfrRjXz3EEqjWyk7/cLWSiiaC6xxpTbCkazZcGZuYDsGQX6idlB9g5Znum64rFSN1x14b/S8vfIToWVMKukTdgma6vVV2RP+RKmScpFwu0/e2bwaP0H8D3f1FJrY4Y66LiORJKCt8iSZ0tM1Q8wYFH+fB/0PeAkInuFavF4jgrf5EWSTqshaitZpOZHlA4zAxjq3jO7P4TQiD9zTIcAniRrAHt3qkUbDoDa9tbugjFMMooh6m+szNAGLsMmMmCsKE5Fvwp3262bkohPCc5uIHdcuHwzGRqw1PtnabJRfaBZ0zi+lKP7Rt/hUVijw+NiQEv4/TNigiVQHaYmJItU4MaaXawxVB7Jp2DmWTFw+c2UJli/Qr7jxrmvuByBP0RuOv1dKSjKQBwr9nB8WKKFdHA7R64xsbIqcdhKu/Bk0Ve9ssqmmh0G42QfLsTzCSGUJu93EyKQkLCWj4moqTz/o5Kfkb3fwUnck8WvsRbFy6zWY9VF72+swgiMBogxxlqiVSnbWgHqjcyZngn2rFBPRuo8nr4BwfsVgqqzR9E8D5wgwFzV1cgnAXiDAVkFX7L9yJ3+QLWdprlanPSaG/eLtTmw9ZdgToFyJ3sh7s8pZTtTDiiOB5Jf8afxGS+ADk4NOqxsK/2ezG/+gVa0fZm22KgmiMtfAH3QtRj1KYPIJ7CQP9lNk0gx+v6e4vuoTJjzOlvNzu2etkSV0mKqJtXuOd/g==

I have reviewed my options and I still need help. I would like to hire an outside consultant to review this case to provide guidance about what I might be missing.

This person reviews your notes and gives you this helpful advice: In this case, it is important to consider the details that would cause abnormalities in Jesse’s physiological (metabolic) state at the time of the accident. You should completely examine her regular dietary habits, her past medical history, and her blood glucose and lipid levels. You should also make sure that you continue as in depth as possible in these lines of investigation.

7.5 Follow Up Questions

You have uncovered almost all the information necessary to explain Jessie’s health issues, but something still does not add up: specifically, why is she having these problems now and not all of her life? For example, if she has an inborn error of one of the genes encoding for CAT I or CAT II, you would expect that she would have always suffered from bouts of hypoglycemia. You discuss all the results with the physician you are working with and she suggests that you never actually asked Jessie what medication she was taking for the seizures she was having! It may be nothing, but what an oversight! The following new investigation is now available:

Ask again about past medical history including a list of current medications

Results: She reported, “I take an anticonvulsant drug, valproic acid, to control the seizures. Why, what does that have to do with anything?”

Investigate the physiological side effects of valproic acid

You quickly look up the side effects of valproic acid on your smart phone; it can cause nausea and vomiting, anorexia, carnitine deficiency, and abnormal bleeding, in patients on certain diets. You ask Jessie, and she says that she has experienced none of these—as far as she knows…

The investigation into the potential side effects of valproic acid has opened up seven new investigation options! Review your previous results so far in this case and consider whether this new information provides any logical explanation for Jessie’s odd metabolic limitations. What would you like to investigate next? The new options opened are:

Ask Jessie to think hard about whether she has been vomiting recently

Result: Jessie restates that she has not had any bouts of nausea or vomiting recently. She is mildly annoyed by this question.

Ask Jessie to think hard about whether she might have a carnitine deficiency

Result: Jessie responds with a puzzled look and says: “Umm… I don’t think so…but what is carnitine anyway?”. The physician you are shadowing steps in and clarifies that Jessie would not know whether she has a carnitine deficiency or not.

Look for abnormal bleeding in the GI tract

Result: You request that Jessie submit to an endoscopy and a colonoscopy. However, the physician you are shadowing disagrees with you - this is not a necessary set of procedures since Jessie does not report any bleeding and does not have any other apparent symptoms that would justify doing these procedures. She also notes that bleeding in the GI tract, even if it is found, does not explain the symptoms that Jessie is exhibiting.

Measure blood levels of carnitine

Result: [Carnitine] = 5 µmol/L (normal range: 24-64 µmol/L)

Jessie has a severe carnitine deficiency! Carnitine is synthesized in humans from the amino acids methionine and lysine, but it is also acquired in the diet. As the name implies, carnitine is especially abundant in meat and dairy products. Because a typical omnivorous diet provides ~75% of a person’s carnitine, carnitine is sometimes considered a vitamin. However, since it can be synthesized de novo this means that it is not a true vitamin. Valproic acid depletes carnitine stores in the body by multiple mechanisms but rarely results in true carnitine deficiency in most people. Something to consider: Why is Jessie experiencing carnitine deficiency? Is there any other aspect about her that might make her particularly sensitive to this side-effect of valproic acid?

Measure blood levels of CoA

Result: Levels of Coenzyme A are normal

Measure blood levels of valproic acid

Result: Valproic acid and its metabolites are detected in the blood. Levels are normal and appropriate for the dose that Jessie is taking to control her seizures

Send Jessie to a counselor to discuss the possibility that she might be anorexic

Result: Jessie is deeply insulted by the insinuation; she has already stated that she eats a high calorie, but vegan, diet and takes your suggestion as an insinuation that she has been lying to you. She restates that she eats regularly and abundantly.

7.6 Final Assessment

Question 7.18

ZwwwGm0ARdxgoAKCm1q+zq4QBL7kdhpPfNCEHryZD+Bo8MMD7NkNYnqnaaxi5y6seXPh6RK3CdlE7+EjcP/PHB9Re/747wcEEzJiAtbMli6hs8et0UltlF5jwnzK/h5wHypXNsgSYJ3G9TLaeFs0HrWdtWCLV8hj7PjU1iTmDXbRBvGqdQV0fpnFCJ5q4sNE7aE7ECddForEgwCSDsZ2zKRgHAcB/RiM4PfCzgyrAVLCk7rPmJdApiBdWt7N3jKsnbn00dfWoQJH3btChhjkE9QZL/QSQMaZy31DLvP0fjiQQSveTCj2otQ/2r1lg/NEu9rtWbetuByZz0M6kei9La2yEI1lOaExxTUulrt4m9HQ+GI2xbV33FZZEWOrWjdv5+IwVpdxcCYW1GiP+RZEfdmxmDt5eJ1n8mNhOeKGzJFIonzvyeE8Y24iiHWpMHTN0Og916/cYnTXNd7vHDX7Vt7p3UtTP9Pkb2mZ847QFdQDaVW4rfIClewFJZuwnhuA7n3S1v+P9nExGJH/YeJFhNOKpVrzSlVVJz5qFq0JoCYPAiZfpsnRZobXxO83+stx8fX3yDbVaR+K7i8mmhNAT+iB2wIV7+eTiMTO3KXzLZJIWnb7EnntTbvTHL2aznu53EVt2d4/fDUbu9tVz79pylYqfpaR7OnNicmDL3CwI0LpxBM8T0FZsTNt7VDCDEyej78TUJ+lg1RhUG3SVx/azG1Fj/mxHbPbEnCUESVtPXieffamxbqkH+EEb0qhslayP4TXYMobE8uRw/VHKk12/kZNiG5P2Wuqt7plMSxOHho3pDi0fe0NH06gcqy7esr6ayN04Ma80fMuj53XL77KhJkbqsc3jYStAb3E7vufvFgsqnuM/WO1O+O9YZ74OsyIUaJiEL5MaSx/OMmYYjpUpFv4XVU+4VdlpUVzmkWSj94BNqDRCzVg6NRpyS4OMsnQ5/zWtxGZQ2d9i09Iwf7Gzcyjvt0HbPHitlg4uFMNtZF9Q/VpMLUSQcDlgXv0EQ0GFcXjMhqUKBWvI7wEIivHUetOVeMQQo624aDui2UbjtZbHFL8yIIhqjAgZfs=Question 7.19

IC7l58xhJBg74aWnutCDfB35TQ5LCX+/vdXseikNvchsJNN+WxsV3F3Xsk1NVwzssQlWU920FtWmIJ4tuhODU+DGHI9R1Aj/kHPBC9+iaKPHk2ss3L2mqs9Io9u0p3pnlOGubj1nM1QG35yJsArAbk3IXwbGH0t1uD2l3QXE41hzCvAfpnhb9W93cdldKxw2wB2gScA2I9WjVdqW5aHQyZ1ML4AJGGc6juFR0IUan1z9ma020FCTrw0C9P28k6dnSBOY317/UWCXK/R8fsHR1DkCUbdSs/LPocAxZUIan5HnL5ZlUmTuteSB4btbLkS6hSv9DTU+D6KAvYM/kpUtZPM3NKG/lKVHI8qdwuP7jIfvhwnMF1An/zVJY2iWS/tl8jy7bf8YUeaYqxi22D83QTNauyJdzoNhLDsypYOOCOyV+jSPC1EbsRmiODJfGqTswPl1Icvk4zn08fMWuYpoHYHa1f4/2nZF5m869/FbDgVZajhpiGT1ARS6YS1tURrgsbQQvEm8+ZM03DefcamdX9GATnjSSrCjYmMTPyEneUm4yNB27VZD+OLXloWUdlCa0FIkFEVKz5EjqZsNvAV/QCbBFgwligGxY0juFu4tKetTSJQy5BYKTObdvR/a1ggV4iXrT8xZ5SAIMOO8XYCDbdr8CFoBacGoPrDPLx8HKXaQ0AJFQsUhXHOxWzzlmb0/+zNvwtcgnjKsS5jDdKhhQYwCp+NvtUASDq6Ac1X/iAoo+JvSyx+gfHdL1XA11cvRvc3Lqm0jM9r6Ht6T5CHr0IuR2mZ3hVRzgDTNZSK0rGl+iduEqInUkkmStkf/l8WhuHdAq4dzdTSytKYclBVXccRZbvcKgnw7zowbP4xvPa8RHatjhndeZcRTjB4RPTH2Wv9TjYUJRezwaFD9oawBRaoENVtyXfw91MUomTfg2af++ApYWmWmELCoB9txTEHhWMfb492wvmUAviEr6j6W1RWX+9uRkJRlVdcqFCi2MG2FZKpeHiduWeYXjjfKIYkitB1N55CLhow1oebuKbiZjgWUB4LNBvLbAtME/Ri5F0W/6xJG/AydcP/DUVf+dPsEbVNLGuhhmecWGLdaC43l3Rjkl0AUCmPj1WhZCd6AkVeUYgWw7yn6uDaCWMQWfchf9MoOh2a/SZpehjXOMC6F/0pggXhiKWHvxkuRmxd6K2p/3hsku7Jg+U4kbU55Uj8U5T2cGYv/EpEjOteSuSOcouv9CMnnfaIegZzsuaVWMzpYvvQxSfpCdWz11dumGZaRnzhh6n5E/e7NEmQ1BW3Mm6Sbwqk1Qzi1XROJlXbRINMi6inNIJ2bGg1GO2Pho0nRyOm6FdiqEHvX7TvNnN4o2X2glfkZc1aOPYAaw4yzlIdefiITA0pCELT7i8nTo91heNmOxewhoWHvL9B87QwJj65FN1dyyLVkcqhtd2kWz4Km0EQx8FMw5rlftnKZN8yJaq381t0ugjKBPANy04LTL1I1I+q1OOLYTa/nppvIj08=Question 7.20

/zcI7M5tJ+CjWMjPEGy7JVNIA6zF0PWAt3cUXg772DvJGWfliEJYRkd9w1G993XOU7XQjSb7O3YboFp5DGvn5hP5sn7jMtaeAIxvCm0OgvBs2ONTAkWmCzcvay2L4Esf1EBwoosCYn0hYKhaV0g1DVNniwm5sdsC2gq2LR5ETDfoU90p6A/djmQhbuRj5Lqn6IhRzkTw9rIu18MNbQZUfNKTs6ceILHl/vs1F+vLJ6zwKyrz1NoE+W+101WLDNRYJc0h+fDYj3lBy1lxnUwKtfM4b/vdohEvNnCj5eV9b3qy9CWDhRW0L93i82ZeF/OOv3WX/gY4bo6VSG6dYh21+HK3AZnTVAjHm1qmhoTBXBAQ2ilb4AY1zGoanNyMtSXiS3z4oP7kZhGlor+6AF0kf1DtcWdwqcc3YeenoQDQKw44+M6RhxfOxEZuCFW4T9Ff4dt0o23dmHfMgiX8Uo6TPCWkpUAfw0WITKV0aHafDiWhLkLflKgE+3KD+etnYkUftVMJI5lJm73xrzrS5Ilx/l184c4QpqoNukMhNc2yC+7HewdaPP3IzyZLbjPWKIuGObpya4YLertBIHqzkiwwj23bxOatOOpsgBQA9lw2IYRVqXE/HGzKg8W5S5GJJygRb0gnchgsuDw2w+Czwhut7rmDfMunBn9Ph+GoRiunYp/mGrZX8tJnBoP62pTnx2JIKw+6AO+9gtrqJlHkcGTmrGXXiWQd/PqR911ZoZS1dzaCFawhOko+LgcyQscdJ/j8AzL0XlljT8RwfaVovfzlPOG4W1RjPRqO/cwfV5inoQBT+izbhlAKfFXuWxpCGMGV+TRNw7iAjdi529JGJpaAGJeQZ/lDG47Twz1d1NOyBDuIWSujcmxh5bdqLZRd+gf7zv8OyDi2ePr3WrqNAWn6MfjxCe8a4Wu88CfkgiT8qpO2QPLdnVZ2N6WRdDM81cTRLhk0uIk8+JXBQ38onshhKu3Lu5S75hK4pUXHJ8pLTbrtcsE65IKOgSVsi994tlz9m9xQn2QDyqteY9v63SZKn/yThgXCaXZsKmjCZyrlsQH7GyTKGSn54qtAnwymQslfcJIJpNazfMCX0IZvftvFz5kp6pkwmTEloul9KTx9GEiv731dCmdnAcii2S5G0HqApFRigQzBV2K5wvbXMFbbvCFw2Wn+GES2hCxq9/2rsm5/YKuUlDo84dXhn1JCh3jdKI5Ufd6FfdPWUlqY/r3BBVEdX/2O9H5vEYhwmwsGsrvEtUHy1CrvQ/0zkLF87ym6pUOWebeaeA38LHQgWoqe5bDW8IJi2ewveHpZhb/cXy2h1GoVGjAe+hUEO9+bOCMiw5sAP/KRV7OflacsyPZD2x9dbCDsoeXXNlgijSjaDAumJg+Y0Rh37exa7Mz9ar343WEADkCHZUUYSgysRwebN6Bwqo0mSSV+5+MWLyFjRI0t8mLh8uwzDqqKiBRfXfQH8yhsViszdVnEXdFTlautlsJgzfEdmh6v9i9TeHTeTh5CRewmDnbNgMGJuviwLOYt06P6iWjEQV1XtD4lH/mkwq3GeVc7CMTS+1tCJ7nDx1kHfjRQYNLSEzjVArVu8MfOSczHZXU4A77ljqR8SPf4uIHKgVIGEt5q8zh8PqPCyPnXuYlFyOKMeE1CsJsQvaCXDWGiO+0+hEB0amqVjziKDTOfvEZlcL892Ub2ynoKA/YzzsADpO8ALi69YLzzpQ2ETfrwLEhOyIzesDpIN/B9FkFrDwgS0vxoM3cp5teRgv9br6XkWAuaKoPuLgdIeTEMHn8ntuSsCbw1XDt1EP+rGSsqIUxTAbY/z/5o+nfbMf2GbRE8lW4OBJUQ0GdTy0HgVdg0rGJkyBvUo+DoC4MBAkmrqElRcuRUw1lnpIJA5PpYDSI6fAViPiOA0Kt3S9EZhFDsfITK2kp4Q9j6d18Np3MgpQQxWn5ThTNOseZTnmx/H+4LhMdBz2Np+0vOQDoi9R+pgVhtdx5qLivifqnfH4h0EYF6z7DjPBnj717XwzEiT+whuQV1Ne4kl0gn1ljWexO6eYu+1hHBzdJkzGo67EARS5qBiFrfBz5oP0b9EEl1l0F1O6UH+IsdySmFhF0RvhGffqr8yQRxRkJKFf9w2JiVdP9uRrNduM/xhOGP30mm1ahIE/VYVom4j6FmP29r/kY7ZfgAkOsN5u5gr4SnCZdz0b0HiDCaBUqJScd3bxkmOKwQxt/rKD1frj2ocZuyuSZWyTqOFZVS6b7DnE8OQXa9pzaGlseE3p87hw2MP/9Pa8WzO9Thng90AgkWxrloq1TthloZQQ4RHuedxtluQ6qMvu567J0rYGJ3Kg3odsg=Question 7.21

5SUOClvpFBZup+cs0ow1xYzhkikL6gNNOOHAgiK/kNKHT1DuCSZcc04TPVENgGV+2MI1LSsu+LCtenLUgWExDWy30cYGBM/yLE3QWa0Y/3nFhoqFa4B6SUz36YXW8+Ghy8t55lG3qu9/yV3CNiyQiPISdUJIStZ2PEG9KMNNdA400B9dLYJxpTa3i70KWDgmVYCbg1geW+ulzk+dlpele6/noDBnbRn3w9X4I/LlTICACr1lgE4MM3eLhs2Y1OMUnbgNodwh+XB8jYgZTdRLFpGyxBQY7Vz20/B7GqV8/Cb0UeOjb4ueGbKe2ok3m93BRQQUdQ4J6c9VGGmopMn8tdUvig/et1u585LW0oaGLclu7TnupCzZ9P81C9nCfD88rqeQ2xPdNULqpzAtsrEYhvJCkKkJi7/p0f3sCXb/bc46j7lJGbJbPICHZt54NTtK+suTp84jsERDaulFyC6JS4PHci+eJiCPzagwktGN5mIh6jHtqAZUV2dI+OsasFOn3O4fHLUIpbvPZ7uMtcNbdTt66LL0qNpsda+EnESUMCWefRdpSahv9pYFGVQW5iVU273HRI6eCscCxmfFqeDWtdinK8ydx/Ctd44cOEADvCVAmWuYxFJMRX9mIblP180IZBVbb6fXIpx3Zr3rszwIpL1tVbT3CN0jkNCdXBfSy4gDcMsxrXZ80O7jALY0m+QyjwV7Cmw1De/aaRNVRdCaArgsnD6Yco04HlzWkzwhZB39LM0yOBhDZpWvtkMTVVudeSuHETlkBLR4HuD5F3nYz6kMbPxQ+0tmpYn+iq7tN3gJ0WYNO9X77FUhPhEhzo/e1cdkMKBOpKhgAafTIRcP/LdLmHQ+FXqFoc9aZr2pnjtmeI4s3WxqHelnWIAVIw20zPs0jYtIzqUsjGYwFFgMLQamvKQtKSPET+dmOyfyXqOmsArFJTre0XgzseVgUQS7kmLhjBE1hdZuLdkcqY2omBR0Ou2wzx2m2BtfoYc1Cp8XXdQmUaJuG1cv4SjVydRpUh52G/7SJkWa2POusLdlD7NoRXh1HSGRNBsEwgEXNf+vWChqbRX7GpICe4meDyaLmhuYrCEVPyWhzl5i+xoF1jrGLnBOhT3AlJ5HaPfUdvNegh74bTLqmZp68Y2szyoTA3qjMQyIeL9xsgbfDpMJ93FfzOi/UC+LbINQSh2SsS3duxP6xgAHWG1vOiFTTegc9kbiHWLeIBHW1bKHn8XGCg4yvFzFHjSoAioY2IBTALBEduer6+X/DYVQo9WCVuejnEguxFSwb63SuY9pgMbvBzLjKz/bhTaSifF6k2LiDx/ZqCYUBOciVZSaVK+E5zHxS5JYvkqQiSlLYYBgqcT/wEW4j7GoUtkztDQJ7M3zVrngOZV0Xxf1YMJ5jXSriUH0xtitC/83Ric1sx93kJHxavx2jtTLwAmggI8rqmQsyJU+SaCDfabCasFyqTD6F9jgq8tthzkq770R8Ozn0+5eDGMIHP9vzrxIJTNA3HvTHsZYL8WmHwwRRUJaZ+Hca/vUgLuMJAGBnF84TX9SEd3Ce9mNt+9ihBuqb1uCuMdOAvP6LSGNe45E/5DjA17EMux04485dYCmKo4xxLbEfhb1vy7Vi0zHWG1zT4b6N0kxaWNi0gCb454gHioczytXXDfaAY8tpgxg805Uot3599qU/Thxo+Db2SZ7qaj33M3ErfDBuoBQtpr6oCUjTIu6mWO3CQoATjgkMFDkL0C1wtAVtPUF3bnWRCvstZIzNpHC0OEOG3EoM2Vcxgsp3X5VCLruOtwtPb/UvcZeMUy47RTrzmbNiJm63OcvPSMI/HG/y5kzuws8WSVHnebFR6flu3JmMUSKjUKFr2RZpzEFCgn1LP887N9GRmx3AkDL59TlQ7RjT0X/AMsqv81ss5ouy0Uebl322dirOdPvB1b35NZ0TNW9Alh9VgGjnsAHh6B0N+QaFNf5f3BTvxADDqlaBvBedM3jEMyj+Fy6jQqqIqU563CZAktmXIaHbh+jdWrCTjl90iHgwsktmRXDIiCJOUzQcNxUZTgRuPG86xeHeZhbb9IBdEs3CKTGzNCnYGXbMY/shyzvY/LKrMX6hgUOAJf7i5QvjGUqxSY0/mbTGuqsp9TAfd/TYfpNTmLh2sxgdlyDlPPao/DbOiIxr1OKzLukM9v45vWxx+0khoA+cv3XpMXTtS18aHKvVh/mVgV02fnwRycSTJGyy+Rf++Fuq7yISnOWU3i4nju1tpjcR6p9O0SU58KMTLa7Question 7.22

lkOQfTvcKaiWnEOyMbkdP7pIaJ/7LsrZM0x6rOMzboEPeAwEw5hlLzs31vna6LtzFqmEpnU1eCKpPEYFnN88BFMxm4mh+eMglcKSsRkhMFZmP8CDMgrSYEmthfhId44cLBOQ8LIvrdRXTSjdxpmvfvJ9ytpU+FpVdNcBdAXd5ZQMuOXLZGEDTpfDHU8NAQTnne0R+wnbl99NcP/qY3tduOqjbr5SgMaTDHq2PP/e4e1BShFNpajjZ3sLA6rJW+iSkDt/o905eDHyFelbCyeMzdpspFU900JO9+09bJOkebb0FBJ091iN4gbDDCs3mwOYWfoCj6/BJSPoCpZuUq6+R1E5XBREQIk3+3cyr7DgWIjeWBHTE+CSBPn7YT5RHP3EghiRL5GHl04sV7GvYJhpeumXaN6zrIwsN+Cl/AqQ9yToQb7+Bqqc2Lkbudzrr0momrwxWwR5kVMmqilx4kbhTaKpV9b7cSWccGib3xIf9yejkCQHOcdEvQjDHrcO0G4kNVR34HzNbExxB3oo/V3WoENV9BNq4Ktexafq6KQpy1vzDuQmBghXLht8ydDqB6KJwbzJ6kL34ErtooAfxWu4vbcjGfSYvLR9O9OpCEl6v5o2KTv+x/cKfUYeowAylHGc5/zX2KEvodievVSu3Z2lDBEBVz98SWTOsY/lAQ7OpGBbBgWxubtE115yEOpCNvmpcKVmxaeOEBMwXmJzOoTJbDR6mQ4HjZKv/4xcPZi5R9g+zkgpXKXSfvYFvjRxUNFfb/HbDGg4eOtZmF9DWXMbjeolcib98pZuFbj95qrORZA/1a5z4S26Su1/vraRW8bB2bgj2hDJ3yD2/FPyA/7pJJ7M+S9+T+td0ywSh4QObjo+FLb8KkwGP4P9dPDjG3QVLWj8szPfE8cCW/G2SAEFOsWN0Bty9V7Z+zO+ympcKfxpwsSXmrdDBfg5/XpS8DZaEb29E7eQBAj/216gWlm0UuRI48XcgrMy0hLI34DgUx58ttiGp85qitRJOSSuvujwK8ENYATdufIUbzKDAvG1D43AQZFJ5oH9lRKTbXtIbIEyOZPAUYqsxDNDBiuzKjnb03WiW4ruidd1u9tG58xeX786vBFsNsBGPHJ+zo0GKfycCgBiM2HUvOwC1Ke69DXavlQSYveelAleUDELWkw9JmB2SGoiinNBDYCxRWBMDjZr8geY1ze7WRljj7IG1Hg7EsX20MKhxXNrkGJVZSj8ktStszOzCp3n04qrk8JRT4jgFmN7EAlzdsSLnBazwnGBLZE8jPJlEXqxOxoTqh7VGa5ee3IYtJVv+rVsXdWQK2+KpYHHfkAsHtrAOAXGERvWug1IHqLxprbSjyHHuRocb167VhasTcEAR2R4IFo2WHjHAglF0r9l2g8fA/P+zuiYhpIXoFKcE7k0gatC2K2obYGCxwvfvTIcsxz/AmAoPW33vaF1CX+/FhW6ktWksIVzRDD7xl17q4YJFH3gT53HNtkL+EcmOLCrT70CzZwTFAGcY07/FTJWjVtZV9Aot7RlfYb5MPGe1YdxhV4Swxr6ZUiYTGPhFIdNkFBLvK2o9gzLNZ0h/dFdQf1uEb3QgTdgeVbohUXAsACapETke5YwMZbJzGr8UAT97QE1dQctnVJO4/ANabTjtzRgABJ8dJxs+8F9GX2jlz39O5CVS9W7pQewPEYaZOVJycl7prJF1jR2ruMN+DXwlHVOfQUDzxO4Mupx5ZEMfe+durkFLZMwkjc2OCj5hR2F4dJNEeMbcvHAfpeDI7Qhug5+GSgbn19XqhgGGSZc/c5uKKuBZt29L2pXUFI=Question 7.23