Approaches to Power Distance

The critically acclaimed film Slumdog Millionaire is about Jamal, a Mumbai teen who grew up in the city slums and became a contestant on the Indian version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? Jamal endures brutal police interrogation on suspicion of cheating because the show’s producers cannot imagine that he could know so much. This may seem shocking to some people in the United States, where upward mobility is a value and underdogs become folk heroes. Why?

It has to do with a culture’s ideas about the division of power among individuals, a concept known as power distance. In India, social status is far more stratified than in the United States. The caste system—

Status differences in a culture result in some groups or individuals having more power than others. But a person’s position in the cultural hierarchy can come from sources besides social class, including age, job title, or even birth order. In high power distance cultures (like India, China, and Japan), people with less power accept their lower position as a basic fact of life. They experience more anxiety when they communicate with those of higher status. And they tend to accept coercion as normal and avoid challenging authority. People in low power distance cultures (such as the United States, Canada, Germany, and Australia) tolerate less difference in power between people and communicate with those higher in status with less anxiety. They are more likely to challenge the status quo, consider multiple options or possibilities for action, and resist coercion.

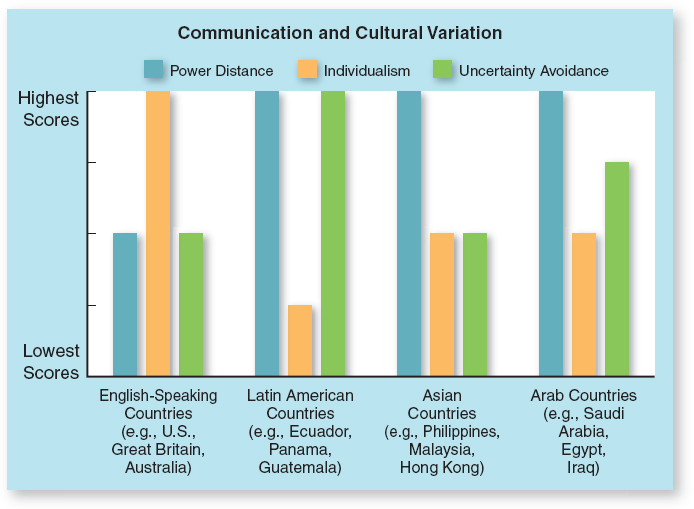

Figure 5.2 shows how different types of cultures vary in their value of power distance, as well as how they differ on the other cultural dimensions of individualism and uncertainty avoidance.