3.3.1 Constructing Gestalts

Printed Page 93

Constructing Gestalts

One way we form impressions of others is to construct a Gestalt, a general sense of a person that’s either positive or negative. We discern a few traits and, drawing upon information in our schemata, we arrive at a judgment based on these traits. (As discussed earlier in this chapter, schemata are the mental structures we use to interpret information during the perception process.) The result is an impression of the person as a whole rather than as the sum of individual parts (Asch, 1946). For example, suppose you strike up a conversation with the person sitting next to you at lunch. The person is funny, friendly, and attractive—characteristics associated with positive information in your schemata. You immediately construct an overall positive impression (“I like this person!”) rather than spending additional time weighing the significance of his or her separate traits.

Gestalts form rapidly. This is one reason why people consider “first impressions” so consequential. Gestalts require relatively little mental or communicative effort. Thus, they’re useful for encounters in which we must render quick judgments about others with only limited information—an interview at a job fair in which you have only a few minutes to size up the interviewer, for instance. Gestalts also are useful for interactions involving casual relationships (contacts with acquaintances or service providers) and contexts in which we are meeting and talking with a large number of people in a small amount of time (business conferences or parties). During such exchanges, it isn’t possible to carefully scrutinize every piece of information we perceive about others. Instead, we quickly form broad impressions and then mentally walk away from them. But this also means that Gestalts have significant shortcomings.

The Positivity Bias In 1913, author E. H. Porter published a novel titled Pollyanna, about a young child who was happy nearly all of the time. Even when faced with horrible tragedies, Pollyanna saw the positive side of things. Research on human perception suggests that some Pollyanna exists inside each of us (Matlin & Stang, 1978). Examples of Pollyanna effects include people believing pleasant events as more likely to happen than unpleasant ones, most people deeming their lives “happy” and describing themselves as “optimists,” and most people viewing themselves as “better than average” in terms of physical attractiveness and intellect (Matlin & Stang, 1978; Silvera, Krull, & Sassler, 2002).

Pollyanna effects come into play when we form Gestalts. When Gestalts are formed, they are more likely to be positive than negative, an effect known as the positivity bias. Let’s say you’re at a party for the company where you just started working. During the party, you meet six new coworkers for the first time and talk with each of them for a few minutes. You form a Gestalt for each. Owing to the positivity bias, most or all of your Gestalts are likely to be positive. Although the positivity bias is helpful in initiating relationships, it also can lead us to make bad interpersonal decisions, such as when we pursue relationships with people who turn out to be unethical or even abusive.

The Negativity Effect When we create Gestalts, we don’t treat all information that we learn about people as equally important. Instead, we place emphasis on the negative information we learn about others, a pattern known as the negativity effect. Across cultures, people perceive negative information as more informative about someone’s “true” character than positive information (Kellermann, 1989). Though you may be wondering whether the negativity effect contradicts Pollyanna effects, it actually derives from them. People tend to believe that positive events, information, and personal characteristics are more commonplace than negative events, information, and characteristics. So when we learn something negative about another person, we see it as “unusual.” Consequently, that information becomes more salient, and we judge it as more truly representative of a person’s character than positive information (Kellermann, 1989).

Sometimes the negativity effect leads us to accurate perceptions of people. One of the women who rejected Ted Bundy’s request for assistance at Lake Sammamish Park reported that she had seen him “stalking” other women be fore he approached her. This information led her to form a negative Gestalt before he even talked with her—an impression that saved her life. But just as often, the negativity effect leads us away from accurate perception. Accurate perception is rooted in carefully and critically assessing everything we learn about people, then flexibly adapting our impressions to match these data. When we weight negative information more heavily than positive, we perceive only a small part of people, aspects that may or may not represent who they are and how they normally communicate.

Question

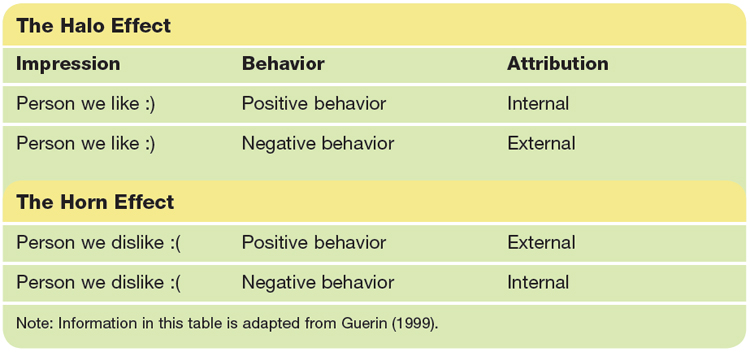

Halos and Horns Once we form a Gestalt about a person, it influences how we interpret that person’s subsequent communication and the attributions we make regarding that individual. For example, think about someone for whom you’ve formed a strongly positive Gestalt. Now imagine that this person discloses a dark secret: he or she lied to a lover, cheated on exams, or stole from the office. Because of your positive Gestalt, you may dismiss the significance of this behavior, telling yourself instead that the person “had no choice” or “wasn’t acting normally.” This tendency to positively interpret what someone says or does because we have a positive Gestalt of them is known as the halo effect (see Table 3.3).

Halo Effect

Watch this clip to answer the questions below.

Question

Want to see more? Check out the Related Content section for additional clips on horn effect and algebraic impressions.

The counterpart of the halo effect is the horn effect, the tendency to negatively interpret the communication and behavior of people for whom we have negative Gestalts (see Table 3.3). Call to mind someone you can’t stand. Imagine that this person discloses the same secret as the individual described above. Although the information in both cases is the same, you would likely chalk up this individual’s unethical behavior to bad character or lack of values.