7.6 COMPETENTLY MANAGING YOUR NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

Printed Page 238

Competently Managing Your Nonverbal Communication

Ways to improve your nonverbal expression

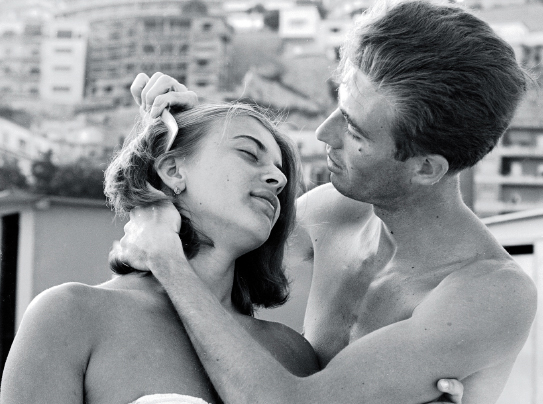

As you interact with others, you use various nonverbal communication codes naturally and simultaneously. Similarly, you take in and interpret others’ nonverbal communication instinctively. Look again at the Beaver family photo (on the next page). While viewing this image, you probably don’t think, “What’s Samson’s mouth doing?” or “Gee, Frances’s arm is touching Samson’s shoulder.” When it comes to nonverbal communication, although all the parts are important, it’s the overall package that delivers the message.

Given the nature of nonverbal communication, we think it’s important to highlight some general guidelines for how you can competently manage your nonverbal communication. In this chapter, we’ve offered very specific advice for improving your use of particular nonverbal codes. But we conclude with four principles for competent nonverbal conduct, which reflect the three aspects of competence first introduced in Chapter 1: effectiveness, appropriateness, and ethics.

First, when interacting with others, remember that people view your nonverbal communication as at least as important as what you say, if not more so. Although you should endeavor to build your active listening skills (Chapter 5), and use of cooperative language (Chapter 6), bear in mind that people will often assign the greatest weight to what you do nonverbally.

Second, nonverbal communication competence is inextricably tied to culture. In our discussion, you’ve repeatedly seen the vast cultural differences as to what is appropriate in body movements (kinesics), space (proxemics), touch (haptics), and time (chronemics), to mention just four. Part of competently managing your nonverbal communication is knowing the cultural display rules for appropriate nonverbal expression prior to interpersonally interacting within a culture, and then adapting your nonverbal communication to match those rules. In addition, competent managers of nonverbal communication are respectful of cultural differences. When someone from another culture uses more or less touch than you, has a different orientation toward time, or adjusts personal distance in ways at odds with your own practice, your ethical obligation is to be tolerant and accepting of this difference, rather than dismissive or disparaging, and to adapt your own nonverbal communication in ways sensitive to the validity of this difference.

Third, be sensitive to the demands of interpersonal situations. For example, if an interaction seems to call for more formal or more casual behavior, adapt your nonverbal communication accordingly. Remind yourself, if necessary, that being interviewed for a job, sharing a relaxed evening with your roommate, and deepening the level of intimacy in a love relationship all call for different nonverbal messages. You can craft those messages through careful use of the many different nonverbal codes available to you.

Finally, remember that verbal communication and nonverbal communication flow with one another. Your experience of nonverbal communication from others and your nonverbal expression to others are fundamentally fused with the words you and they choose to use. As a consequence, you cannot become a skilled interpersonal communicator by focusing time, effort, and energy only on verbal or only on nonverbal elements. Instead, you must devote yourself to both, because it is only when both are joined as a union of skills that more competent interpersonal communication ability is achieved.