Issues in Interpersonal Communication

Adapting to influences on interpersonal communication

As we move through the twenty-

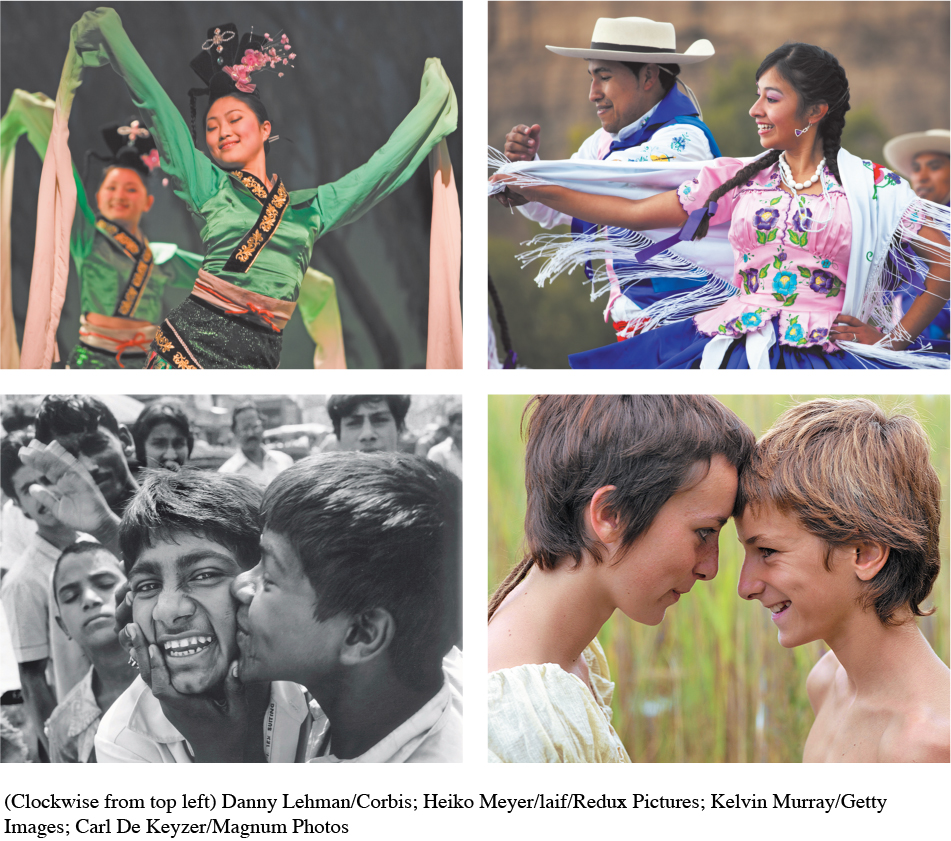

CULTURE

In this text, we define culture broadly and inclusively as an established, coherent set of beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices shared by a large group of people (Keesing, 1974). Culture includes many different types of large-

Throughout this book, and particularly in Chapter 5, we examine differences and similarities across cultures and consider their implications for interpersonal communication. As we cover this material, critically examine the role that culture plays in your own interpersonal communication and relationships.

GENDER AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION

Gender consists of social, psychological, and cultural traits generally associated with one sex or the other (Canary, Emmers-

28

Each of us also possesses a sexual orientation: an enduring emotional, romantic, sexual, or affectionate attraction to others that exists along a continuum ranging from exclusive homosexuality to exclusive heterosexuality and that includes various forms of bisexuality (APA Online, n.d.). You may have heard that gays and lesbians communicate in ways different from “straights” or that each group builds, maintains, and ends relationships in distinct ways. But as with common beliefs about gender, research shows that same-

focus on CULTURE

Intercultural Competence

29

When GM first began marketing the Chevy Nova in South America, it sold few cars. Why? Because no va means “it won’t go” in Spanish. When Coke first began selling in China, its attempt to render Coca-Cola in Mandarin (Ke-kou-ke-la) translated as “bite the wax tadpole!”

Intercultural communication challenges aren’t limited to language. The “hook ’em horns” gesture (index and pinky finger raised) used by Texas football fans means “your wife is cheating on you” in Italy. And simply pointing at someone with your index finger is considered rude in China, Japan, Indonesia, and Latin America.

Throughout this text, we discuss cultural differences in communication and how you can best adapt to them. Such skills are essential, given that hundreds of thousands of college students choose to pursue their studies overseas, international travel is increasingly common, and technology continues to connect people worldwide. As a starting point for building your intercultural competence, consider these suggestions:

Think globally. If the world’s population was reduced in scale to 1,000 people, only 56 would be from Canada, Mexico, and the United States.

Learn appropriateness. Take the time to learn the practices of other cultures before interacting with their people.

Be respectfully inquisitive. When you’re unsure about how to communicate, politely ask. People will view you as competent—

even if you make mistakes— when you sincerely try to learn and abide by their cultural expectations. Use simple language. Avoid slang and jargon. A phrase like “Let’s cut to the chase” may make sense if you’re originally from Canada or the United States, but it won’t necessarily be understood elsewhere.

Be patient with yourself and others. Becoming interculturally competent is a lifelong journey, not a short-

term achievement.

discussion questions

How has your cultural background shaped how you communicate with people from other cultures?

What’s the biggest barrier that keeps people of different cultures from communicating competently with each other?

ONLINE COMMUNICATION

Radical changes in communication technology have had a profound effect on our ability to interpersonally communicate. Mobile devices keep us in almost constant contact with friends, family members, colleagues, and romantic partners. Our ability to communicate easily and frequently, even when separated by geographic distance, is further enhanced through online communication. In this book, we treat such technologies as tools for connecting people interpersonally—