The Components of Self

At Delphi in ancient Greece, the temple of the sun-god Apollo was adorned with the inscription Gnothi se auton—“Know thyself.” According to legend, when one of the seven sages of Greece, Chilon of Sparta, asked Apollo, “What is best for people?” the deity responded with that simple admonition. More than 2,500 years later, these words still ring true, especially in the realm of interpersonal communication and relationships. To understand our interactions with others and the bonds we forge, we must first comprehend ourselves. But what exactly is “thyself” that we need to know?

The self is an evolving composite of self-awareness, self-concept, and self-esteem. Although each of us experiences the self as singular (“This is who I am”), it is actually made up of three distinct yet integrated components that evolve continually over time, based on your life experiences.

SELF-AWARENESS

Self-awareness is the ability to view yourself as a unique person distinct from your surrounding environment and to reflect on your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. According to sociologist George Herbert Mead (1934), self-awareness helps you have a strong sense of your self because during interpersonal encounters, you monitor your own behaviors and form impressions of who you are from such observations. For example, your best friend texts you that she has failed an important exam. You feel bad for her, so you text her a comforting response. Your self-awareness of your compassion and your observation of your kindhearted message lead you to think, “I’m a caring and supportive friend.”

38

As we’re watching and evaluating our own actions, we also engage in social comparison: observing and assigning meaning to others’ behavior and then comparing it with ours. Social comparison has a particularly potent effect on self when we compare ourselves to people we wish to emulate. When we compare favorably when measured against respected others, we think well of ourselves; when we don’t compare favorably, we think less of ourselves.

You can greatly enhance your interpersonal communication by practicing a targeted kind of self-awareness known as critical self-reflection. To engage in critical self-reflection, ask yourself the following questions:

What am I thinking and feeling?

Why am I thinking and feeling this way?

How am I communicating?

How are my thoughts and feelings influencing my communication?

How can I improve my thoughts, feelings, and communication?

The ultimate goal of critical self-reflection is embodied in the last question: How can I improve? Improving your interpersonal communication is possible only when you accurately understand how your self drives your communication behavior. In the remainder of this chapter, and in the marginal Self-Reflection exercises you’ll find throughout this book, we help you make links between your self and your communication.

39

SELF-CONCEPT

Self-concept is your overall perception of who you are. Your self-concept is based on the beliefs, attitudes, and values you have about yourself. Beliefs are convictions that certain things are true—for example, “I’m an excellent student.” Attitudes are evaluative appraisals, such as “I’m happy with my appearance.” Values represent enduring principles that guide your interpersonal actions—for example, “I think it’s wrong to . . . ”

Your self-concept is shaped by a host of factors, including your gender, family, friends, and culture (Vallacher, Nowak, Froehlich, & Rockloff, 2002). As we saw in the opening story about Eric Staib, one of the biggest influences on your self-concept is the labels others put on you. How do others’ impressions of you shape your self-concept? Sociologist Charles Horton Cooley (1902) argued that it’s like looking at yourself in the “looking glass” (mirror). When you stand in front of it, you consider your physical appearance through the eyes of others. Do they see you as attractive? overweight? too tall or too short? Seeing yourself in this fashion—and thinking about how others must see you—has a powerful effect on how you think about your physical self. Cooley noted that the same process shapes our broader self-concept: it is based in part on your beliefs about how others see you, including their perceptions and evaluations of you (“People think I’m talented, and they like me”) and your emotional response to those beliefs (“I feel good/bad about how others see me”). Cooley referred to the idea of defining our self-concepts through thinking about how others see us as the looking-glass self.

self-reflection

Consider your looking-glass self. What kinds of labels do your friends use to describe you? your family? How do you feel about others’ impressions of you? In what ways do these feelings shape your interpersonal communication and relationships?

Some people have clear and stable self-concepts; that is, they know exactly who they are, and their sense of self endures across time, situations, and relationships. Others struggle with their identity, remaining uncertain about who they really are, what they believe, and how they feel about themselves. The degree to which you have a clearly defined, consistent, and enduring sense of self is known as self-concept clarity (Campbell et al., 1996), and it has a powerful effect on your outlook, health, and happiness. Research suggests that people who have a stronger, clearer sense of self (i.e., higher self-concept clarity) have higher self-esteem, are less likely to experience negative emotions (both in response to stressful situations and in general), and are less likely to experience chronic depression (Lee-Flynn, Pomaki, DeLongis, Biesanz, & Puterman, 2011). In simple terms, high self-concept clarity helps you weather the unpredictability and instability of the world around you. To test your self-concept clarity, take the Self-Quiz on page 40.

In considering your self-concept and its impact on your interpersonal communication, keep two implications in mind. First, because your self-concept consists of deeply held beliefs, attitudes, and values, changing it is difficult. Once you’ve decided you’re a compassionate person, for example, you’ll likely perceive yourself that way for a long time (Fiske & Taylor, 1991).

Second, our self-concepts often lead us to make self-fulfilling prophecies—predictions about future interactions that lead us to behave in ways that ensure the interaction unfolds as we predicted. Some self-fulfilling prophecies set positive events in motion. For instance, you may see yourself as professionally capable and highly skilled at communicating, which leads you to predict job interview success. During an interview, your prophecy of success leads you to communicate in a calm and confident fashion, which impresses the interviewers. In turn, their reaction confirms your prophecy. Other self-fulfilling prophecies set negative events in motion. I once had a friend who believed he was unattractive and undesirable. Whenever we went out to parties, his self-concept would lead him to predict interpersonal failure. He would then spend the entire time in a corner staring morosely into his drink. Needless to say, no one tried to talk to him. At the end of the evening, he’d say, “See, I told you no one would want to talk to me!”

40

skillspractice

Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

Overcoming negative self-fulfilling prophecies

Identify a communication problem you experience often (e.g., social anxiety).

Describe situations in which it occurs, including what you think, say, and do.

Use critical self-reflection to identify how your thoughts and feelings shape your communication.

List things you could say and do that would generate positive results.

In similar situations, block negative thoughts and feelings that arise, and focus your attention on practicing the positive behaviors you listed.

SELF-ESTEEM

Self-esteem is the overall value, positive or negative, that we assign to ourselves. Whereas self-awareness prompts us to ask, “Who am I?” and self-concept is the answer to that question, self-esteem is the answer to the follow-up question, “Given who I am, what’s my evaluation of my self?” When your overall estimation of self is negative, you’ll have a meager sense of self-worth and suffer from low self-esteem. When your evaluation of self is positive, you’ll enjoy high self-esteem.

Your self-esteem strongly shapes your interpersonal communication, relationships, and physical and mental health (Pyszczynski, Greenberg, Solomon, Arndt, & Schimel, 2004). People with high self-esteem report greater life satisfaction; communicate more positively with others; experience more happiness in their relationships; and exhibit greater leadership ability, athleticism, and academic performance than do people with low self-esteem (Fox, 1997, 1992). High self-esteem also helps insulate people from stress and anxiety (Lee-Flynn et al., 2011).

41

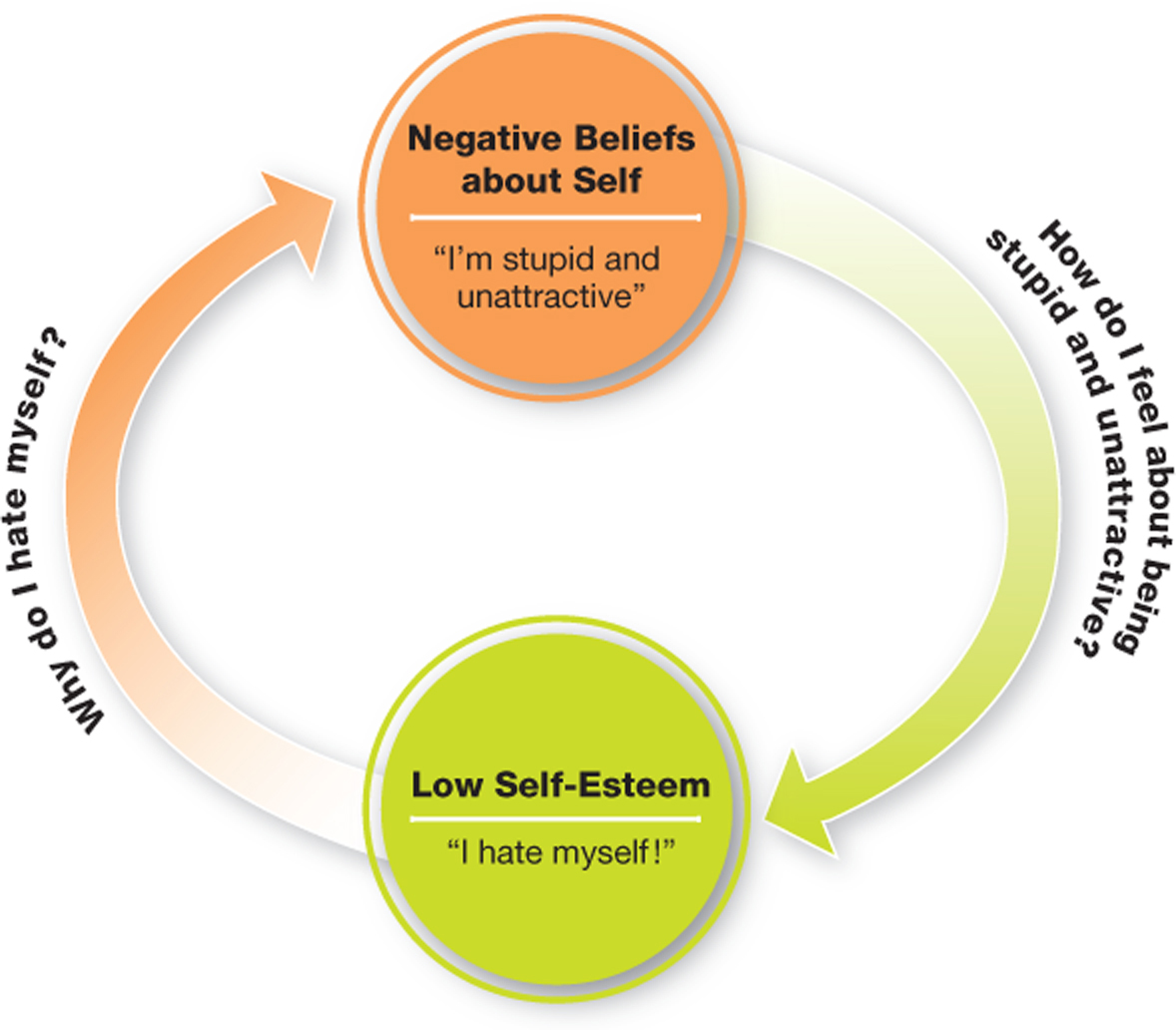

By contrast, people with low self-esteem are more likely to believe that friends and romantic partners think negatively of them (Gaucher et al., 2012) and, as a consequence, are less likely to share their thoughts and feelings with others. This lack of expressivity ultimately undermines their close relationships (Gaucher et al., 2012). In addition, low self-esteem individuals experience negative emotions and depression more frequently (Orth, Robius, Trzesniewski, Maes, & Schmitt, 2009), resulting in destructive feedback loops like the one depicted in Figure 2.1.

Measuring Up to Your Own Standards The key to bolstering your self-esteem is understanding its roots. Self-discrepancy theory suggests that your self-esteem is determined by how you compare to two mental standards (Higgins, 1987). The first is your ideal self, the characteristics (mental, physical, emotional, material, and spiritual) that you want to possess—the “perfect you.” The second is your ought self, the person others wish and expect you to be. This standard stems from expectations of your family, friends, colleagues, and romantic partners as well as cultural norms. According to self-discrepancy theory, you feel happy and content when your perception of your self matches both your ideal and your ought selves (Katz & Farrow, 2000). However, when you perceive your self to be inferior to both your ideal and your ought selves, you experience a discrepancy and are likely to suffer low self-esteem (Veale, Kinderman, Riley, & Lambrou, 2003).

Research looking at self-discrepancy theory suggests three things to consider (Halliwell & Dittmar, 2006; Phillips & Silvia, 2005). First, women report larger ideal self-discrepancies than do men. This isn’t surprising, given the degree to which women are deluged with advertising and other media emphasizing unattainable standards for female beauty (see Focus on Culture on p. 43). Second, for both men and women, self-discrepancies impact a host of specific emotions and feelings linked to self-esteem. For instance, people who have substantial ideal and ought self-discrepancies are more likely to report feeling dejected, disappointed, hopeless, and upset about themselves. Finally, self-discrepancies are most apparent and impactful to us in situations in which we become consciously self-aware: looking in a mirror, watching ourselves on video, or getting direct feedback from others. After watching an unflattering video clip of yourself posted online or getting an unsatisfactory employee evaluation, you may suddenly feel that you’re “not the kind of person you should be”—resulting in negative emotions and plummeting self-esteem.

42

This latter finding suggests an important relationship implication. If you live your life surrounded by people who constantly criticize you, belittle you, or call attention to your flaws, you are more likely to have wider self-discrepancies and lower self-esteem. Alternatively, if your social network supports you and praises you for your unique abilities, your self-discrepancies will diminish and your self-esteem will rise. Thus, a critical part of maintaining your life happiness and self-esteem is avoiding or limiting contact with people who routinely tear you down and surrounding yourself with people who build you up.

What’s more, it doesn’t matter whether you think you’re immune to others’ opinions. Research looking at people who said that they couldn’t “care less” about what other people think of them found that their self-esteem was just as strongly impacted by approval and criticism as people who reported valuing others’ opinions (Leary et al., 2003). In short, receiving others’ approval or criticism will boost or undermine your self-esteem whether you think it will or not.

Improving Your Self-Esteem Your self-esteem can start to improve only when you reduce discrepancies between your self and your ideal and ought selves. How can you do this? Begin by assessing your self-concept. Make a list of the beliefs, attitudes, and values that make up your self-concept. Be sure to include both positive and negative attributes. Then think about your self-esteem. In reviewing the list you’ve made, do you see yourself positively or negatively?

Next, analyze your ideal self. Who do you wish you were? Is this ideal attainable, or is it unrealistic? If it is attainable, what would you have to change to become this person? If you made these changes, would you be satisfied with yourself, or would your expectations for yourself simply escalate further?

Third, analyze your ought self. Who do others want you to be? Can you ever become the person others expect? What would you have to do to become this person? If you did all of these things, would others be satisfied with you, or would their expectations escalate?

Fourth, revisit and redefine your standards. This step requires intense, concentrated effort over a long period of time. If you find that your ideal and ought selves are realistic and attainable, move to the final step. If you decide that your ideal and ought selves are unrealistic and unattainable, redefine these standards so that each can be attainable through sustained work. If you find yourself unable to abandon unrealistic and unattainable standards, don’t be afraid to consult with a professional therapist or another trusted resource for assistance.

43

focus on CULTURE: How Does the Media Shape Your Self-Esteem?

How Does the Media Shape Your Self-Esteem?

Korean American comedian Margaret Cho describes herself as a “trash-talkin’ girl comic.” In this excerpt from her one-woman show The Notorious C.H.O., she offers her thoughts on self-esteem:

You know when you look in the mirror and think, “Oh, I’m so fat, I’m so old, I’m so ugly”? That is not your authentic self speaking. That is billions upon billions of dollars of advertising—magazines, movies, billboards—all geared to make you feel bad about yourself so that you’ll take your hard-earned money and spend it at the mall. When you don’t have self-esteem, you will hesitate before you do anything. You will hesitate to go for the job you really want. You will hesitate to ask for a raise. You will hesitate to defend yourself when you’re discriminated against. You will hesitate to vote. You will hesitate to dream. For those of us plagued with low self-esteem, improving [it] is truly an act of revolution! (Custudio, 2002)

Cho is right. We live in an “appearance culture,” a society that values and reinforces extreme, unrealistic ideals of beauty and body shape (Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999). In an appearance culture, standards for appearance are defined through digitally enhanced images of bodily perfection produced by the mass media (Field et al., 1999). When we internalize media standards of the perfect body and perfect beauty, we end up despising our own bodies and craving unattainable perfection (Jones, Vigfusdottir, & Lee, 2004). This results in low self-esteem, depression, and, in some cases, self-destructive behaviors such as eating disorders (Harrison, 2001).

discussion questions

Consider your own body. How have images of ideal beauty in magazines and on TV influenced your ideas about what constitutes an attractive body?

How do your feelings about your body affect your self-esteem? How do they affect your interpersonal communication and relationships?

Finally, create an action plan for resolving any self-discrepancies. Map out the specific actions necessary to eventually attain your ideal and ought selves. Frame your new standards as a list of goals, and post them in your planner, cell phone, personal Web page, bedroom, or kitchen to remind yourself of these goals. Since self-esteem can’t be changed in a day, a week, or even a month, establish a realistic time line. Then implement this action plan in your daily life, checking your progress as you go.