Introduction to Chapter 3

68

69

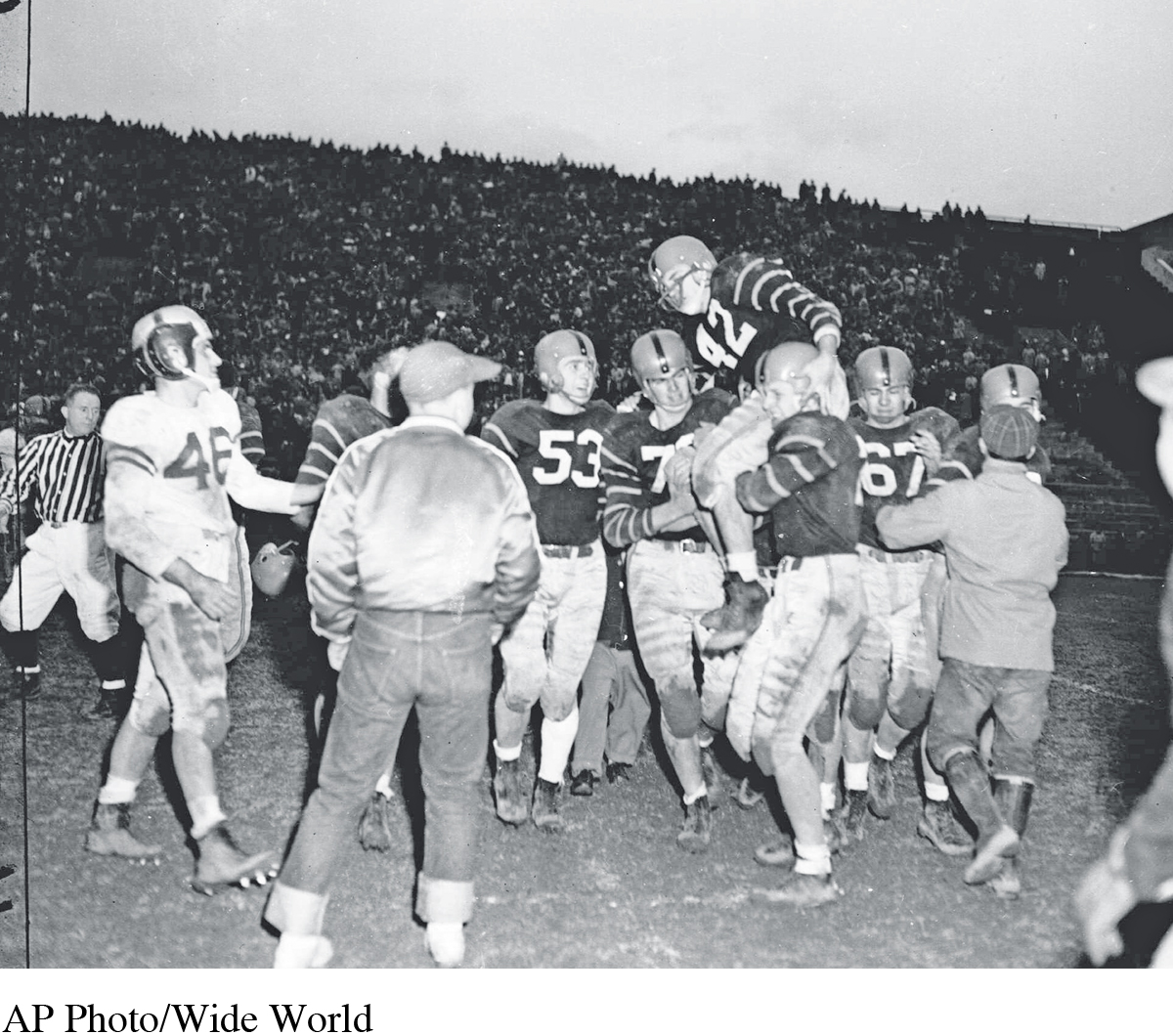

In November 1951, the Dartmouth College football team traveled to Princeton University to play the final game of the season.1 For Princeton, the contest had special significance: it was the farewell performance of its All-American quarterback, Heisman Trophy winner Dick Kazmaier. Princeton had an 18–1 record at home during Kazmaier’s tenure, and they walked onto their turf that day undefeated for the season.

From the opening kickoff, it was a brutal affair. Kazmaier suffered a hit late in the second quarter that broke his nose, caused a concussion, and forced him from the field. In retaliation, Princeton defenders knocked two consecutive Dartmouth quarterbacks out of the game, one of them with a broken leg. Several fights erupted, and referees’ flags filled the afternoon air, most of them signaling “roughing.” Although Princeton prevailed, both sides left the stadium bitter about the on-field violence.

In the days that followed, perceptions of the game diverged wildly, depending on scholastic allegiance. Princeton supporters denounced Dartmouth’s “dirty play,” and the Daily Princetonian decried Dartmouth for “deliberately attempting to cripple Kazmaier.” The Dartmouth student paper countered, accusing Princeton’s coach of urging his players to “get” the Dartmouth quarterbacks.

Perceptual differences weren’t limited to players and attendees. A Dartmouth alumnus in the Midwest heard reports of his team’s “disgusting” play and requested a copy of the game film. After viewing it, he sent a telegram to the university: “Viewing of the film indicates considerable cutting of important parts. Please airmail the missing excerpts.” Why did he believe that the film had been edited? Because when he watched it, he didn’t perceive any cheap shots by his team.

70

Intrigued by the perceptual gulf between Princeton and Dartmouth devotees, two psychologists—Albert Hastorf from Dartmouth and Hadley Cantril from Princeton—teamed up to study reactions to the game. What they found was striking. After viewing the game film, students from both schools were asked, “Who instigated the rough play?” Princeton students overwhelmingly blamed Dartmouth, while Dartmouth students attributed the violence to both sides. When questioned about whether Dartmouth had intentionally injured Kazmaier, Princeton students said yes; Dartmouth students said no. And when asked about penalties, Dartmouth students perceived both teams as committing the same number. Princeton students said Dartmouth committed twice as many as Princeton. Though the two groups saw the same film, they perceived two very different games.

Although Hastorf and Cantril examined rival perceptions of a historic college football game, their results tell us much about the challenges we face in responsibly perceiving other people. Each of us perceives the “games,” “cheap shots,” and “fights” that fill our lives in ways skewed to match our own beliefs and desires. All too often we fail to consider that others feel just as strongly about the “truth” of their viewpoints as we do about ours. Every time we perceive our own behavior as beyond reproach and others’ as deficient, see others as exclusively to blame for conflicts, or neglect to consider alternative perspectives and feelings, we are exactly like the Dartmouth and Princeton fans who could perceive only the transgressions of the other team.

But competent interpersonal communication and healthy relationships are not built on belief in perceptual infallibility. Instead, they are founded on recognition of our perceptual limitations, constant striving to correct perceptual errors, and sincere effort invested in considering others’ viewpoints.

71

Perception is our window to the world. Everything we experience while interacting with others is filtered through our perception. While information seems to enter our conscious minds without bias, our perception is not an objective lens. Instead, it’s a product of our own mental creation. When we perceive, we actively create the meanings we assign to people, their communication, and our relationships, and we look to our perception—not reality itself—to guide our interpersonal communication and relationship decisions. This is why it’s essential to understand how perception works. By honing our awareness of the perception process, we can improve our interpersonal communication and forge better relationships.

In this chapter, we explore how you can improve your perception to become a better interpersonal communicator. You’ll learn:

How the perception process unfolds, and which perceptual errors you need to watch for

The influence that gender and personality have in shaping your perception of others and your interpersonal communication

How you form impressions of others, and the benefits and limitations of the methods you use

Strategies for improving your perceptual accuracy