Passion and Grief

PASSION

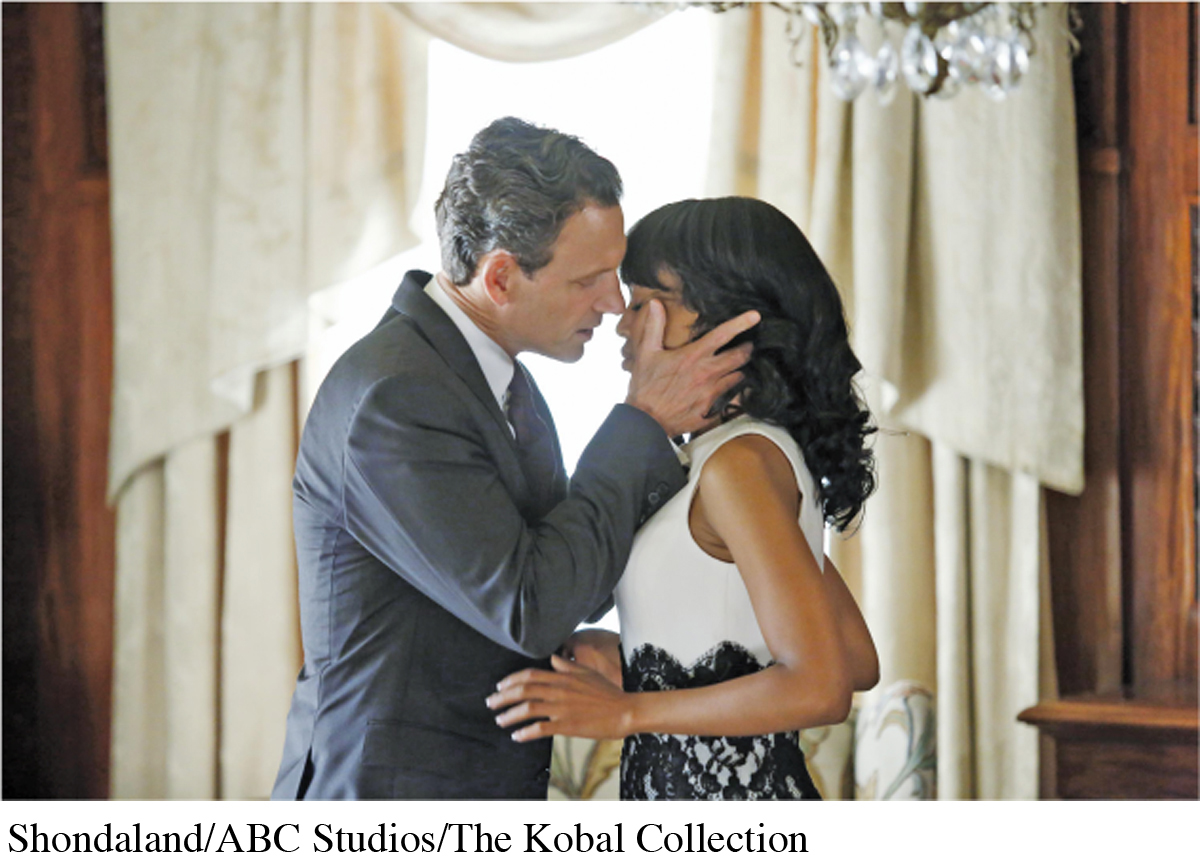

Few emotions fascinate us more than romantic passion. Thousands of Web sites, infomercials, books, and magazine articles focus on how to create, maintain, or recapture passion. Feeling passion toward romantic partners seems almost obligatory in Western culture, and we often decide to discard relationships when passion fades (Berscheid & Regan, 2005). At the same time, most of us recognize that passion is fleeting and distressingly fragile (Berscheid, 2002).

Passion is a blended emotion, a combination of surprise and joy coupled with a number of positive feelings, such as excitement, amazement, and sexual attraction. People who elicit passion in us are those who communicate in ways that deviate from what we expect (triggering surprise and amazement), whom we interpret positively (generating joy and excitement), and whom we perceive as physically pleasing (leading to sexual attraction).

122

If passion necessarily involves joy, excitement, and sexual attraction, why would we consider passion a challenging emotion? Because passion stems in large part from surprise. Consequently, the longer and better you know someone, the less passion you will experience toward that person on a daily basis (Berscheid, 2002). In the early stages of romantic involvements, our partners communicate in ways that are novel and positive. The first time our lovers invite us on a date, kiss us, or disclose their love, all are surprising events and intensely passionate. But as partners become increasingly familiar with each other, their communication and behavior do, too. Things that were once perceived as unique become predictable. Partners who have known each other intimately for years may be familiar with almost all the communication behaviors in each other’s repertoires (Berscheid, 2002). Consequently, the capacity to surprise partners in dramatic, positive, and unanticipated ways is diminished (Hatfield, Traupmann, & Sprecher, 1984).

self-reflection

How has passion changed over time in your romantic relationships? What have you and your partners done to deal with these changes? Is passion a necessary component of romance, or is it possible to be in love without passion?

Because passion derives from what we perceive as surprising, you can’t engineer a passionate evening by carefully negotiating a dinner or romantic rendezvous. You or your partner might experience passion if an event is truly unexpected, but jointly planning and then acting out a romantic candlelight dinner together or spending a weekend in seclusion cannot recapture passion for both you and your partner. When it comes to passion, the best you can hope for in long-term romantic relationships is a warm afterglow (Berscheid, 2002). However, this is not to say that you can’t maintain a happy and long-term romance; maintaining this kind of relationship requires strategies that we discuss in Chapter 10.

GRIEF

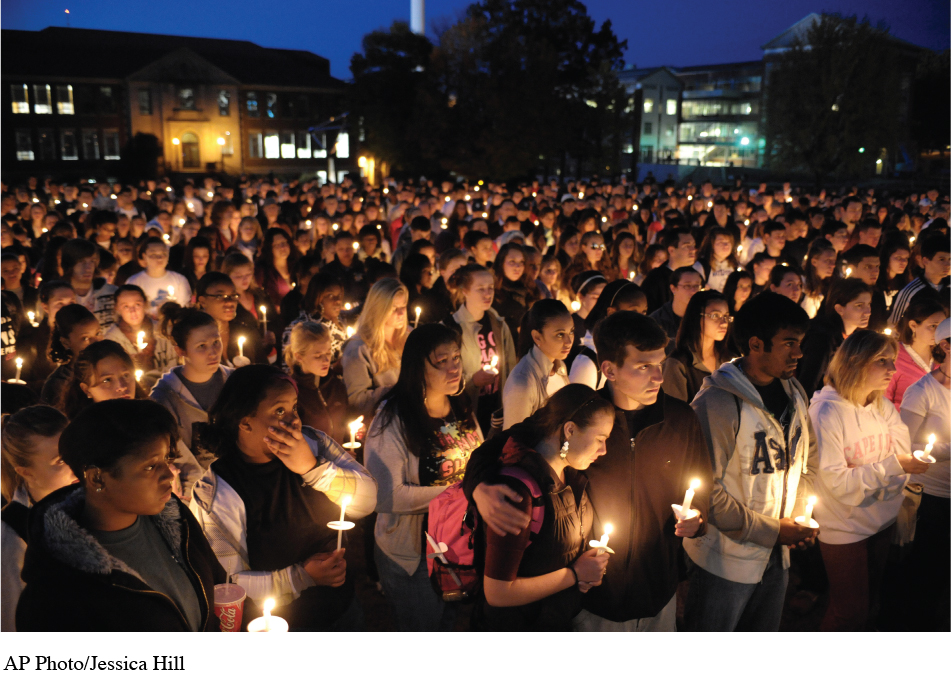

Carlos Arredondo and Lu Jun first met on a 2013 cruise honoring those impacted by the Boston Marathon bombings—including heroes, survivors, and their families. Jun lost his daughter, Lingzi, on that fateful April day; Arredondo is a civilian hero of the bombings who knows about loss from the deaths of his two sons—one from combat in Iraq and the other from suicide. Although they have little else in common, they share the bond of grief. As Arredondo noted: “Sometimes I don’t need to say anything to him. . . . I give him a hug, or touch his shoulders, or shake hands. We sit on the bus together. Hopefully that makes him feel comfort” (Wedge & Sherman, 2014). Arredondo and Jun were not the only ones who found comfort on the cruise. Other passengers had the opportunity to talk with one another about the Boston tragedy, the nightmares that still haunt them, and the ways in which their lives have been irreparably altered by loss—whether it be of loved ones, mobility, the ability to hear, or a general sense of safety and well-being. Arredondo explained: “There’s been a few moments where I shared my experience with some of them, and they help me out, to get it off my chest. And I’ve been listening to a few stories myself. I hope I help out as well. Like family. Like an old friend. It’s amazing how this works” (Wedge & Sherman, 2014).

123

The intense sadness that follows a substantial loss, known as grief, is something each of us will experience. We can not maintain long-term, intimate involvements with other mortal beings without at some point losing loved ones to death. But grief isn’t only about mortality. You’re likely to experience grief in response to any type of major loss. This may include parental (or personal) divorce, physical disability due to injury (as was the case for many of the Boston Marathon victims), romantic relationship breakup, loss of a much-loved job, or even the destruction or misplacing of a valued object, such as an engagement ring or a treasured family heirloom.

Managing grief is enormously and uniquely taxing. Unlike other negative emotions such as anger, which is typically triggered by a onetime, short-lived event, grief stays with us for a long time—triggered repeatedly by experiences linked with the loss.

Managing Your Grief No magic pill can erase the suffering associated with a grievous loss. It seems ludicrous to think of applying strategies such as reappraisal, encounter structuring, or the Jefferson strategy to such pain. Grief is a unique emotional experience, and none of the emotion management strategies discussed in this chapter so far can help you.

Instead, you must use emotion-sharing: talking about your grief with others who are experiencing or have experienced similar pain, or people who are skilled at providing you with much-needed emotional support and comfort. Participating in a support group for people who have suffered similar losses can encourage you to share your emotions. When you share your grief, you feel powerfully connected with others, and this sense of connection can be a source of comfort, as it was for Arredondo, Jun, and the other cruise passengers whose lives were forever changed by tragedy and loss. You also gain affirmation that the grief process you’re experiencing is normal. For example, a fellow support-group participant who also lost his mother to cancer might tell you that he, too, finds Mother’s Day a particularly painful time. Finally, other participants in a support group can help you remember that grief does get gradually more bearable over time.

124

For those of us without ready access to face-to-face support groups, online support offers a viable alternative. Besides not requiring transportation and allowing access to written records of any missed meetings, online support groups also provide a certain degree of anonymity for people who feel shy or uncomfortable within traditional group settings (Weinberg, Schmale, Uken, & Wessel, 1995). You can interact in a way that preserves some degree of privacy. This is an important advantage, as many people find it easier to discuss sensitive topics online than face-to-face, where they run the risk of embarrassment (Furger, 1996).

Comforting Others The challenges you face in helping others manage their grief are compounded by the popular tendency to use suppression for managing sadness. The decision to use suppression derives from the widespread belief that it’s important to maintain a stoic bearing, a “stiff upper lip,” during personal tragedies (Beach, 2002). However, a person who uses suppression to manage grief can end up experiencing stress-related disorders, such as chronic anxiety or depression. Also, the decision to suppress can lead even normally open and communicative people to stop talking about their feelings. This places you in the awkward position of trying to help others manage emotions that they themselves are unwilling to admit they are experiencing.

The best way you can help others manage their grief is to engage in supportive communication—sharing messages that express emotional support and that offer personal assistance (Burleson & MacGeorge, 2002). Competent support messages convey sincere expressions of sympathy and condolence, concern for the other person, and encouragement to express emotions. Incompetent support messages tell a person how he or she should feel or indicate that the individual is somehow inadequate or blameworthy. Communication scholar and social support expert Amanda Holmstrom offers seven suggestions for improving your supportive communication.4

Make sure the person is ready to talk. You may have amazing support skills, but if the person is too upset to talk, don’t push it. Instead, make it clear that you care and want to help, and that you’ll be there to listen when he or she needs you.

Find the right place and time. Once a person is ready, find a place and a time conducive to quiet conversation. Avoid distracting settings such as parties, where you won’t be able to focus, and find a time of the day where neither of you has other pressing obligations.

Ask good questions. Start with open-ended queries such as “How are you feeling?” or “What’s on your mind?” Then follow up with more targeted questions based on the response, such as “Are you eating and sleeping OK?” (if not, a potential indicator of depression) or “Have you connected with a support group?” (essential to emotion-sharing). Don’t assume that because you’ve been in a similar situation, you know what someone is going through. Refrain from saying “I know just how you feel.”

125

skillspractice

Supportive Communication

Skillfully providing emotional support

Let the person know you’re available to talk, but don’t force an encounter.

Find a quiet, private space.

Start with general questions, and work toward more specific questions. If you think he or she might be suicidal, ask directly.

Assure the person that his or her feelings are normal.

Show that you’re attending closely to what is being said.

Ask before offering advice.

Let the person know you care!

Importantly, if you suspect a person is contemplating suicide, ask him or her directly about it. Say, “Have you been thinking about killing yourself?” or “Has suicide crossed your mind?” People often mistakenly think that direct questions such as these will push someone over the edge, but in fact it’s the opposite. Research suggests that someone considering suicide wants to talk about it but believes that no one cares. If you ask direct questions, a suicidal person typically won’t be offended or lie but instead will open up to you. Then you can encourage the person to seek counseling. Someone not considering suicide will express surprise at the question, often laughing it off with a “What? No way!”

Legitimize, don’t minimize. Don’t dismiss the problem or the significance of the person’s feelings by saying things such as “It could have been worse,” “Why are you so upset?!” or “You can always find another lover!” Research shows that these comments are unhelpful. Instead, let the person know that it’s normal and OK to feel as he or she does.

Listen actively. Show the person that you are interested in what is being said. Engage in good eye contact, lean toward him or her, and say “Uh-huh” and “Yeah” when appropriate.

Offer advice cautiously. We want to help someone who is suffering, so we often jump right in and offer advice. But many times that’s not helpful or even wanted. Advice is best when it’s asked for, when the advice giver has relevant expertise or experience (e.g., a relationship counselor), or when it advocates actions the person can actually do. Advice is hurtful when it implies that the person is to blame or can’t solve his or her own problems. When in doubt, ask if advice would be appreciated—or just hold back.

126

Show concern and give praise. Let the person know you genuinely care and are concerned about his or her well-being (“I am so sorry for your loss; you’re really important to me”). Build the person up by praising his or her strength in handling this challenge. Showing care and concern helps connect you to someone, while praise will help a person feel better.