Communicating through Touch

COMMUNICATING THROUGH TOUCH

Using touch to communicate nonverbally is known as haptics, from the ancient Greek word haptein. Touch is likely the first sense we develop in the womb, and receiving touch is a critical part of infant development (Knapp & Hall, 2002). Infants deprived of affectionate touch walk and talk later than others and suffer impaired emotional development in adulthood (Montagu, 1971).

Touch can vary based on its duration, the part of the body being touched, and the strength of contact, and these varieties influence how we interpret the physical contact (Floyd, 1999). Scholars distinguish between six types of touch. We use functional-professional touch to accomplish some type of task. Examples include touch between physicians and patients, between teachers and students, and between coaches and athletes. Social-polite touch derives from social norms and expectations. The most common form of social-polite touch is the handshake, which has been practiced as a greeting in one form or another for over 2,000 years (Heslin, 1974). Other examples include light hugging between friends or relatives, and the light cheek kiss. We rely on friendship-warmth touch—for example, gently grasping a friend’s arm and giving it a squeeze—to express our like for another person. Love-intimacy touch—cupping a romantic partner’s face tenderly in your hands, giving him or her a big, lingering hug—lets you convey deep emotional feelings. Sexual-arousal touch, as the name implies, is intended to physically stimulate another person. Finally, aggressive-hostile touch involves forms of physical violence, like grabbing, slapping, and hitting—behaviors designed to hurt and humiliate others.

235

focus on CULTURE: Touch and Distance

Touch and Distance

Cultures vary in their norms regarding appropriate touch and distance, some with lots of touching and close distance during interpersonal encounters and others with less (Hall, 1966). Often, these differences correlate with latitude and climate. People living in cooler climes tend to be low contact, and people living in warmer areas tend to be high contact (Andersen, 1997). The effect of climate on touch and distance is even present in countries that have both colder and hotter regions. Cindy, a former student, describes her experience juggling norms for touch and distance:*

I’m a Mexican American from El Paso, Texas, which is predominantly Latino. There, most everyone hugs hello and good-bye. And I’m not talking about a short slap on the back—I mean a nice encompassing abrazo (hug). While I can’t say that strangers greet each other this way, I do recall times where I’ve done it. Growing up, it just seemed like touching is natural, and I never knew how much I expected it, maybe even relied on it, until I moved.

I came to Michigan as a grad student. My transition here was relatively smooth, but it was odd to me the first time I hung out with friends and didn’t hug them hello and good-bye. A couple of times on instinct I did greet them this way, and I’ll never forget the strange tension that was created. Some people readily hugged me back, but most were uneasy. Quickly I learned that touching was unacceptable.

Now I find that I hold back from engaging people in this manner. I feel like I’m hiding a part of myself, and it is frustrating. Nonetheless, this is the way things are done here, and I’ve had to adjust. Fortunately, I now have a few friends who recognize my need to express myself in this way and have opened themselves up to it. I’m grateful for that, and through these people a piece of me and my identity is saved.

discussion questions

What has your culture taught you about the use of touch and distance? Are you a high- or low-contact person?

When communicating with people from other cultures, how do you adapt your use of touch and distance?

Cultural upbringing has a strong impact on how people use and perceive touch. For example, many Hispanics use friendship-warmth touch more frequently than do Europeans and Euro-Americans. Researchers in one study monitored casual conversations occurring in outdoor cafés in two different locales: San Juan, Puerto Rico, and London, England. They then averaged the number of touches between conversational partners. The Puerto Ricans touched each other an average of 180 times per hour. The British average? Zero (Environmental Protection Agency, 2002).

236

Because people differ in the degree to which they feel comfortable giving and receiving touch, consider adapting your use of touch to others’ preferences, employing more or less touch depending on your conversational partner’s behavior responses to your touching. If you are talking with a “touchy” person, who repeatedly touches your arm gently while talking (a form of social-polite touch), you can probably presume that such a mild form of touch would be acceptable to reciprocate. But if a person offers you no touch at all, not even a greeting handshake, you would be wise to inhibit your touching.

COMMUNICATING THROUGH PERSONAL SPACE

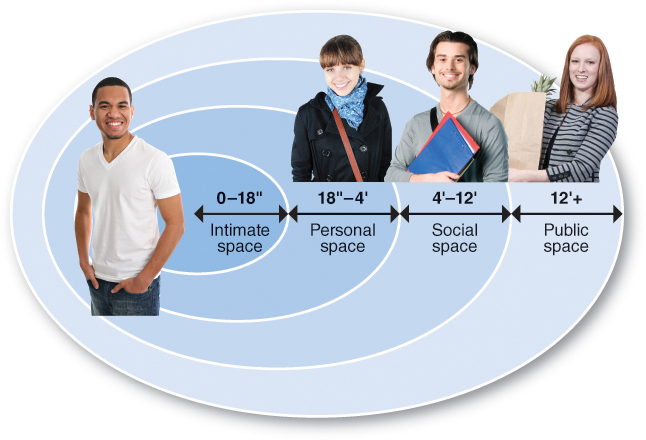

The fourth nonverbal communication code, proxemics (from the Latin proximus, meaning “near”), is communication through the use of physical distance. Edward T. Hall, one of the first scholars to study proxemics, identified four communication distances: intimate, personal, social, and public (Hall, 1966). Intimate space ranges from 0 to 18 inches. Sharing intimate space with someone counts among the defining nonverbal features of close relationships (see Figure 9.1). Personal space ranges between 18 inches and 4 feet and is the distance we occupy during encounters with friends. For most Americans and Canadians, personal space is about your “wingspan”—that is, the distance from fingertip to fingertip when you extend your arms. Social space ranges from about 4 to 12 feet. Many people use it when communicating in the workplace or with acquaintances and strangers. In public space, the distance between persons ranges upward from 12 feet, including great distances; this span occurs most often during formal occasions, such as public speeches or college lectures.

In addition to the distance we each claim for ourselves during interpersonal encounters, we also have certain physical areas or spaces in our lives that we consider our turf. Territoriality is the tendency to claim physical spaces as our own and to define certain locations as areas we don’t want others to invade without permission (Chen & Starosta, 2005). Human beings react negatively to others who invade their perceived territory, and we respond positively to those who respect it (King, 2001). Imagine coming back to your dorm room and finding one of your roommate’s friends asleep in your bed. How would you respond? If you’re like most people, you would feel angry and upset. Even though your roommate’s friend is not violating your personal space (distance from your body), he or she is inappropriately encroaching on physical space that you consider your territory.

237

self-reflection

Which locations in your physical spaces at home and work do you consider your most valued territories? How do you communicate this territoriality to others? What do you do when people trespass? Have your reactions to such trespasses caused negative personal or professional consequences?

What can you do to become more sensitive to differences in the use of personal space? Keep in mind that, as noted earlier in this chapter, North Americans’ notions of personal space tend to be larger than those in most other cultures, especially people from Latin America or the Middle East. When interacting with people from other cultures, adjust your use of space in accordance with your conversational partner’s preferences. Realize, also, that if you’re from a culture that values large personal space, others will feel most comfortable interacting at a closer distance than you’re used to. If you insist on maintaining a large personal space bubble around yourself when interacting with people from other cultures, they may think you’re aloof or distant or that you don’t want to talk with them.

COMMUNICATING THROUGH PHYSICAL APPEARANCE

On the hit TLC show Say Yes to the Dress, Randy Fenoli and other sales associates at Kleinfeld Bridal in New York City help prospective brides find the ideal wedding dresses for what is (for many people) “the most important day of their lives.” The show involves not just finding a dress but finding the dress that fits a bride’s ideal image for how she should look. However, the show is not just about superficial allure. Instead, the choice of dress and accessories conveys a powerful communicative message to others about the bride’s self-identity. As Randy notes, “One of the most important things I tell brides is that you should always choose a gown that really represents who you are, because what you’re doing at a wedding is telling a story about who you are as a person, and as a couple” (Herweddingplanner.com, 2011).

238

Although weddings are an extreme example in terms of the emphasis placed on how we look, our physical appearance—visible attributes such as hair, clothing, and body type—profoundly influences all our interpersonal encounters. In simple terms, how you look conveys as much about you as what you say. And beauty counts. Across cultures, people credit individuals they find physically attractive with higher levels of intelligence, persuasiveness, poise, sociability, warmth, power, and employment success than they credit to unattractive individuals (Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986).

This effect holds in online environments as well. For example, the physical attractiveness of friends who post their photos on your Facebook page has noteworthy effects on people’s perceptions of your attractiveness (Walther, Van Der Heide, Kim, Westerman, & Tong, 2008). That is, if you have attractive friends’ photos on your page, people will perceive you as more physically and socially attractive; if you have unattractive friends, you’ll seem less attractive to others.

self-reflection

Consider your physical appearance, as shown in photos on your Facebook page or other personal Web sites. What do your face, hair, clothing, and body communicate to others about who you are and what you’re like? Now examine friends’ photos on your pages. How might their appearance affect others’ perceptions of you?

What physical appearance characteristics does it take to be judged attractive? Standards of beauty are highly variable, both across cultures and across time periods. But one factor that’s related to attractiveness across cultures is facial symmetry—the degree to which each side of your face precisely matches the other. For example, this can include whether someone’s eyes are the same shape or whether someone’s ears are at the exact same height. People with symmetrical faces are judged as more attractive than people with asymmetrical faces (Grammer & Thornhill, 1994), although perfect facial symmetry may be seen as artificial and unattractive (Kowner, 1996).

Your clothing also has a profound impact on others’ perceptions of you. More than 40 years of research suggests that clothing strongly influences people’s judgments about profession, level of education, socioeconomic status, and even personality and personal values (Burgoon et al., 1996). The effect that clothing has on perception makes it essential that you consider the appropriateness of your dress, the context for which you are dressing, and the image of self you wish to nonverbally communicate. When I worked for a Seattle trucking company, I was expected to wear clothes that could withstand rough treatment. On my first day, I “dressed to impress” and was teased by coworkers and management for dressing as if I were an executive at a large corporation. But expectations like this can change in other situations. During job interviews, for example, dress as nicely as you can. Being even moderately formally dressed is one of the strongest predictors of whether an interviewer will perceive you as socially skilled and highly motivated (Gifford, Ng, & Wilkinson, 1985).

COMMUNICATING THROUGH OBJECTS

Take a moment to examine the objects that you’re wearing and that surround you: jewelry, watch, cell phone, computer, art or posters on the wall, and so forth. These artifacts—the things we possess that influence how we see ourselves and that we use to express our identity to others—constitute another code of nonverbal communication. As with our use of posture and of personal space, we use artifacts to communicate power and status. For example, by displaying expensive watches, cars, or living spaces, people “tell” others that they’re wealthy and influential (Burgoon et al., 1996).

239

COMMUNICATING THROUGH THE ENVIRONMENT

A final way in which we communicate nonverbally is through our environment, the physical features of our surroundings. As the photo of the Google office illustrates, our environment envelops us, shapes our communication, and implies certain things about us, often without our realizing it.

self-reflection

Look around the room you’re in right now. How does this room make you feel? How do the size of the space, furniture, lighting, and color contribute to your impression? What kind of interpersonal communication would be most appropriate for this space—personal or professional? Why?

Two types of environmental factors play a role in shaping interpersonal communication: fixed features and semifixed features (Hall, 1981). Fixed features are stable and unchanging environmental elements, such as walls, ceilings, floors, and doors. Fixed features define the size of a particular environment, and size has an enormous emotional and communicative impact on people. For example, the size of structures communicates power, with bigger often being better. In corporations, it’s often assumed that larger offices equal greater power for their occupants; and historically, the square footage of homes has communicated the occupant’s degree of wealth.

Semifixed features are impermanent and usually easy to change; they include furniture, lighting, and color. We associate bright lighting with environments that are very active and soft lighting with environments that are calmer and more intimate. Color also exerts a powerful effect on our mood and communication: we experience blues and greens as relaxing, yellows and oranges as arousing and energizing, reds and blacks as sensuous, and grays and browns as depressing (Burgoon et al., 1996).