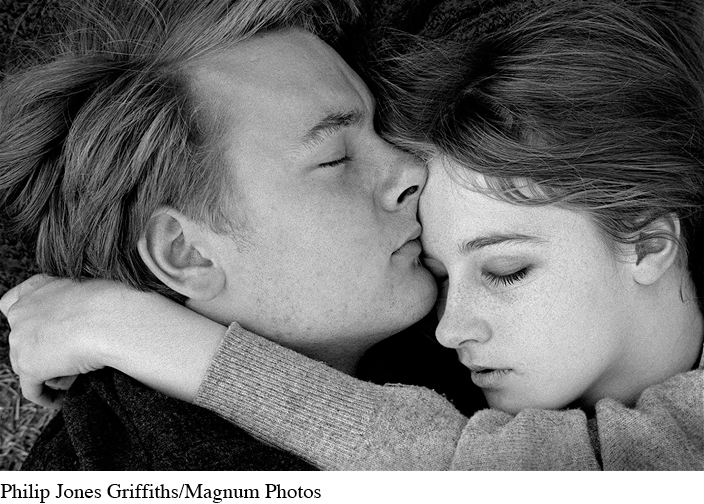

Defining Romantic Relationships

We often think of romantic relationships as exciting and filled with promise—a joyful fusion of closeness, communication, and sexual connection. When researchers Pamela Regan, Elizabeth Kocan, and Teresa Whitlock (1998) asked several hundred people to list the things they associated most with “being in love,” the most frequent responses were trust, honesty, happiness, bondedness, companionship, communication, caring, intimacy, shared laughter, and sexual desire. But apart from such associations, what exactly is romantic love? How does it differ from liking? The answers to these questions can help you build more satisfying romantic partnerships.

LIKING AND LOVING

Most scholars agree that liking and loving are separate emotional states, with different causes and outcomes (Berscheid & Regan, 2005). Liking is a feeling of affection and respect that we typically have for our friends (Rubin, 1973). Affection is a sense of warmth and fondness toward another person, while respect is admiration for another person apart from how he or she treats you or communicates with you. Loving, in contrast, is a vastly deeper and more intense emotional experience and consists of three components: intimacy, caring, and attachment (Rubin, 1973).

288

Intimacy is a feeling of closeness and “union” between you and your partner (Mashek & Aron, 2004).

Caring is the concern you have for your partner’s welfare and the desire to keep him or her happy.

Attachment is a longing to be in your partner’s presence as much as possible.

The ideal combination for long-term success in romantic relationships occurs when partners both like and love each other.

DIFFERENT TYPES OF ROMANTIC LOVE

Though most people recognize that loving differs from liking, many also believe that to be in love, one must feel constant and consuming sexual attraction toward a partner. In fact, many different types of romantic love exist, covering a broad range of emotions and relationship forms. At one end of the spectrum is passionate love, a state of intense emotional and physical longing for union with another (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1992). Studies of passionate love suggest six things are true about its experience and expression. First, passionate love quite literally changes our brains. Neuroimaging studies of people experiencing passionate love suggest substantial activation of brain reward centers, as well as activation of the caudate nucleus—an area associated with obsessive thinking (Graham, 2011). In simple terms, people passionately in love often find the experience intensely pleasurable and may have their thoughts circle constantly around their partners. Second, people passionately in love often view their loved ones and relationships in an excessively idealistic light. For instance, many partners in passionate love relationships talk about how “perfect” they are for each other.

self-reflection

Is passion the critical defining feature of being in love? Or can you fall in love without ever feeling passion? Given that passion typically fades, is romantic love always doomed to fail, or can you still be in love after passion leaves?

Third, people from all cultures feel passionate love. Studies comparing members of individualist versus collectivist cultures have found no differences in the amount of passionate love experienced (Hatfield & Rapson, 1987). Although certain ethnicities, especially Latinos, are often stereotyped as being more “passionate,” studies comparing Latino and non-Latino experiences of romantic love suggest no differences in intensity (Cerpas, 2002).

289

Fourth, no gender or age differences exist in people’s experience of passionate love. Men and women report experiencing this type of love with equal frequency and intensity, and studies using a Juvenile Love Scale (which excludes references to sexual feelings) have found that children as young as age 4 report passionate love toward others (Hatfield & Rapson, 1987). The latter finding is important to consider when talking with children about their romantic feelings. Although they lack the emotional maturity to fully understand the consequences of their relationship decisions, their feelings toward romantic interests are every bit as intense and turbulent as our adult emotions. So if your 6- or 7-year-old child or sibling reveals a crush on a schoolmate, treat the disclosure with respect and empathy rather than teasing him or her.

Fifth, for adults, passionate love is integrally linked with sexual desire (Berscheid & Regan, 2005). In one study, undergraduates were asked whether they thought there was a difference between “being in love” and “loving” another person (Ridge & Berscheid, 1989). Eighty-seven percent of respondents said that there was a difference and that sexual attraction was the critical distinguishing feature of being in love.

Finally, passionate love is negatively related to relationship duration. Like it or not, the longer you’re with a romantic partner, the less intense your passionate love will feel (Berscheid, 2002).

Although the fire of passionate love dominates media depictions of romance, not all people view being in love this way. At the other end of the romantic spectrum is companionate love: an intense form of liking defined by emotional investment and deeply intertwined lives (Berscheid & Walster, 1978). Many long-term romantic relationships evolve into companionate love. As Clyde and Susan Hendrick (1992) explain, “Sexual attraction, intense communication, and emotional turbulence early in a relationship give way to quiet intimacy, predictability, and shared attitudes, values, and life experiences later in the relationship” (p. 48).

Between the poles of passionate and companionate love lies a range of other types of romantic love. Sociologist John Alan Lee (1973) suggested six different forms, ranging from friendly to obsessive and gave them each a traditional Greek name: storge, agape, mania, pragma, ludus, and eros (see Table 11.1 for an explanation of each). As Lee noted, there is no “right” type of romantic love—different forms appeal to different people.

Despite similarities between men and women in their experiences of passionate love, substantial gender differences exist related to one of Lee’s love types—pragma, or “practical love.” Across numerous studies, women score higher than men on pragma (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1988, 1992), refuting the common stereotype that women are “starry-eyed” and “sentimental” about romantic love (Hill, Rubin, & Peplau, 1976). What’s more, although men are often stereotyped as being “cool” and “logical” about love (Hill et al., 1976), they are much more likely than women to perceive their romantic partners as “perfect” and believe that “love at first sight is possible” and that “true love can overcome any obstacles” (Sprecher & Metts, 1999).

290

| Type | Description | Attributes of Love |

|---|---|---|

| Storge | Friendly lovers | Stable, predictable, and rooted in friendship |

| Agape | Forgiving lovers | Patient, selfless, giving, and unconditional |

| Mania | Obsessive lovers | Intense, tumultuous, extreme, and all consuming |

| Pragma | Practical lovers | Logical, rational, and founded in common sense |

| Ludus | Game-playing lovers | Uncommitted, fun, and played like a game |

| Eros | Romantic lovers | Sentimental, romantic, idealistic, and committed |