What Is Interpersonal Communication Competence?

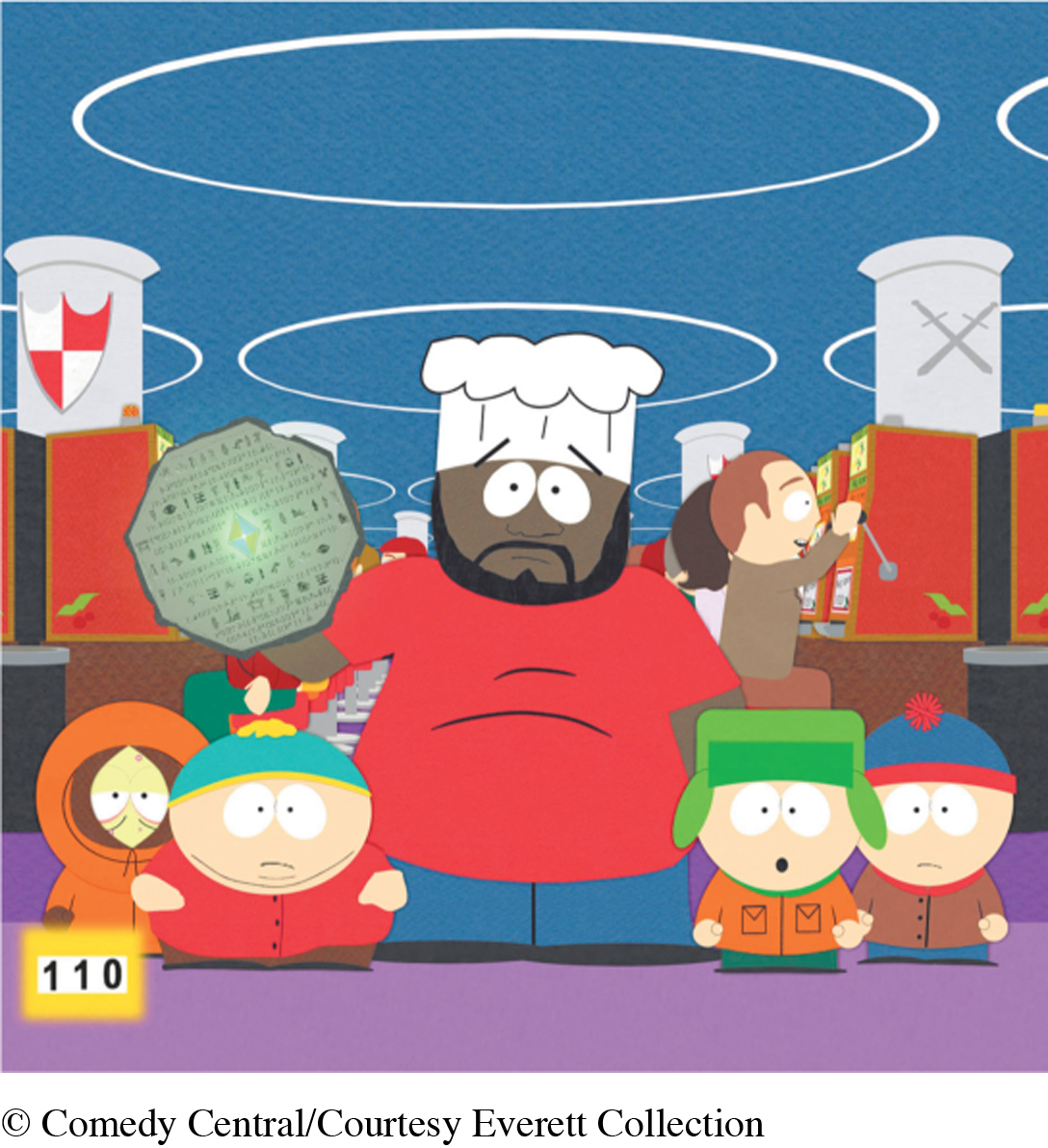

For nine seasons of South Park, Jerome “Chef” McElroy (voiced by the late, great R&B singer Isaac Hayes) was the only adult trusted and respected by the show’s central characters: Kyle, Stan, Kenny, and Cartman. In a routine interaction, the boys—while waiting on the school lunch line—would share their concerns and seek Chef’s counsel. He would do his best to provide appropriate, effective, and ethical advice, often bursting into song. Of course, given his reputation as a ladies’ man, the boys frequently asked him for advice regarding relationships and sex. Chef would answer in vague and allusive ways, trying to remain child appropriate but ending up completely unintelligible. In other instances he’d get carried away, singing about his sexual exploits before remembering his audience. But despite occasional lapses in effectiveness and appropriateness, Chef consistently was the most ethical, kind, and compassionate adult in a show populated by insecure, self-absorbed, and outright offensive characters.

21

Many of us can think of a Chef character in our own lives—someone who, even if he or she occasionally errs, always strives to communicate competently. Often, this person’s efforts pay off; competent communicators report more relational satisfaction (including happier marriages), better psychological and physical health, and higher levels of educational and professional achievement than others (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2002).

Although people who communicate competently report positive outcomes, they don’t all communicate in the same way. No one recipe for competence exists. Communicating competently will help you achieve more of your interpersonal goals, but it doesn’t guarantee that all of your relationship problems will be solved.

Throughout this text, you will learn the knowledge and skills necessary for strengthening your interpersonal competence. In this chapter, we explore what competence means and how to improve your competence online. Throughout later chapters, we examine how you can communicate more competently across various situations, and within romantic, family, friendship, and workplace relationships.

UNDERSTANDING COMPETENCE

self-reflection

Think of an interpersonal encounter in which different people expected very different things from you in your communication. How did you choose which expectations to honor? What were the consequences of your decision? How could you have communicated in a way perceived as appropriate by everyone in the encounter?

Interpersonal communication competence means consistently communicating in ways that are appropriate (your communication follows accepted norms), effective (your communication enables you to achieve your goals), and ethical (your communication treats people fairly) (Spitzberg & Cupach, 1984; Wiemann, 1977). Acquiring knowledge of what it means to communicate competently is the first step in developing interpersonal communication competence (Spitzberg, 1997).

The second step is learning how to translate this knowledge into communication skills—repeatable goal-directed behaviors and behavioral patterns that you routinely practice in your interpersonal encounters and relationships (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2002). Both steps require motivation to improve your communication. If you are strongly motivated to do so, you can master the knowledge and skills necessary to develop competence.

Appropriateness The first characteristic of competent interpersonal communication is appropriateness—the degree to which your communication matches situational, relational, and cultural expectations regarding how people should communicate. In any interpersonal encounter, norms exist regarding what people should and shouldn’t say, and how they should and shouldn’t act. For example, in South Park, Chef commonly struggled when the boys asked him to talk about topics that aren’t considered appropriate for children. Part of developing your communication competence is refining your sensitivity to norms and adapting your communication accordingly. People who fail to do so are perceived by others as incompetent communicators.

22

We judge how appropriate our communication is through self-monitoring: the process of observing our own communication and the norms of the situation in order to make appropriate communication choices. Some individuals closely monitor their own communication to ensure they’re acting in accordance with situational expectations (Giles & Street, 1994). Known as high self-monitors, they prefer situations in which clear expectations exist regarding how they’re supposed to communicate, and they possess both the ability and the desire to alter their behaviors to fit any type of social situation (Oyamot, Fuglestad, & Snyder, 2010). In contrast, low self-monitors don’t assess their own communication or the situation (Snyder, 1974). They prefer encounters in which they can “act like themselves” by expressing their values and beliefs, rather than abiding by norms (Oyamot et al., 2010). As a consequence, high self-monitors are often judged as more adaptive and skilled communicators than low self-monitors (Gangestad & Snyder, 2000).

One of the most important choices you make related to appropriateness is when to use mobile devices and when to put them away. Certainly, cell phones and tablets allow us to quickly and efficiently connect with others. However, when you’re interacting with people face-to-face, the priority should be your conversation with them; if you prioritize your device over the person in front of you, you run the risk of being perceived as inappropriate. This is not a casual choice: research documents that simply having cell phones out on a table—but not using them—during face-to-face conversations significantly reduces perceptions of relationship quality, trust, and empathy compared to having conversations with no phones present (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2012). To avoid this, put your mobile devices away at the beginning of any interaction.

While communicating appropriately is a key part of competence, overemphasizing appropriateness can backfire. If you focus exclusively on appropriateness and always adapt your communication to what others want, you may end up forfeiting your freedom of communicative choice to peer pressure or fears of being perceived negatively (Burgoon, 1995).

Effectiveness The second characteristic of competent interpersonal communication is effectiveness: the ability to use communication to accomplish the three types of interpersonal goals discussed earlier (self-presentation, instrumental, and relationship). There’s rarely a single communicative path for achieving all of these goals, and sometimes you must make trade-offs. For example, a critical part of maintaining satisfying close relationships is the willingness to occasionally sacrifice instrumental goals to achieve important relationalship goals. Suppose you badly want to see a movie tonight, but your romantic partner needs your emotional support to handle a serious family problem. Would you say, “I’m sorry you’re feeling bad—I’ll call you after I get home from the movie” (emphasizing your instrumental goals)? Or would you say, “I can see the movie some other time—tonight I’ll hang out with you” (emphasizing your relationship goals)? The latter approach, which facilitates relationship health and happiness, is obviously more competent.

23

self-reflection

Is the obligation to communicate ethically absolute or situation-dependent? That is, are there circumstances in which it’s ethical to communicate in a way that hurts someone else’s feelings? Can one be disrespectful or dishonest and still be ethical? If so, in what kinds of situations?

Ethics The final defining characteristic of competent interpersonal communication is ethics—the set of moral principles that guide our behavior toward others (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2002). At a minimum, we are ethically obligated to avoid intentionally hurting others through our communication. By this standard, communication that’s intended to erode a person’s self-esteem, that expresses intolerance or hatred, that intimidates or threatens others’ physical well-being, or that expresses violence is unethical and therefore incompetent (Parks, 1994).

To truly be an ethical communicator, however, we must go beyond simply not doing harm. During every interpersonal encounter, we need to strive to treat others with respect, and communicate with them honestly, kindly, and positively (Englehardt, 2001). For additional guidelines on ethical communication, review the “Credo for Ethical Communication” on page 24.

We are all capable of competence in contexts that demand little of us—situations in which it’s easy to behave appropriately, effectively, and ethically. True competence is developed when we consistently communicate competently across all situations that we face—contexts that are uncertain, complex, and unpleasant, as well as those that are simple, comfortable, and pleasant. One of the goals of this book is to arm you with the knowledge and skills you need to meet challenges to your competence with confidence.

24