Motives for Interpersonal Communication

MOTIVES FOR INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION

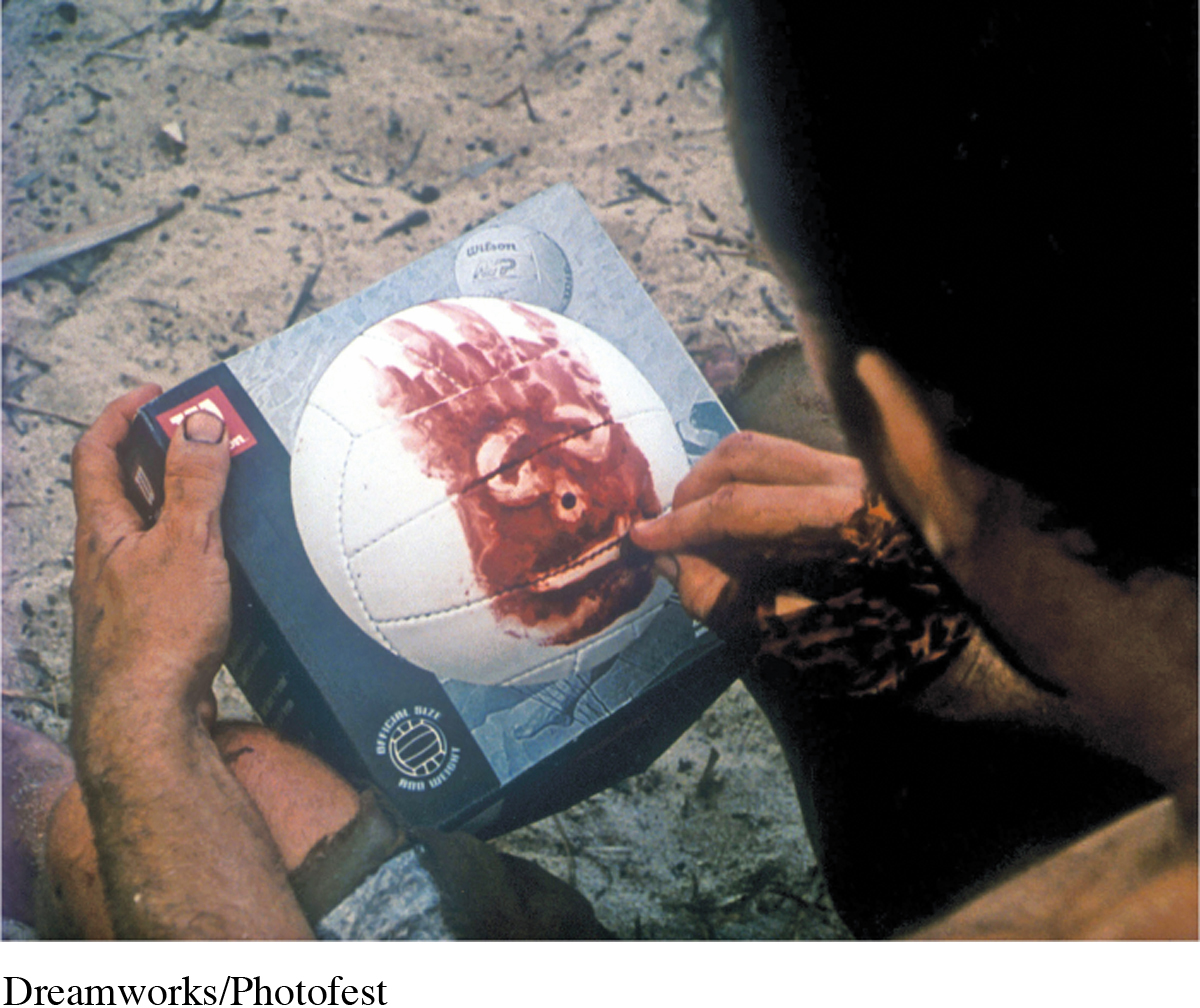

In the movie Cast Away (2000), Tom Hanks plays FedEx executive Chuck Noland, who survives a plane crash at sea, only to find himself alone on an uncharted island. Noland must improvise his survival, learning how to obtain food and fresh water, build a shelter, and create fire. But by far his biggest challenge is dealing with his isolation from others. Realizing that he will be presumed dead by all who knew him and likely live out the rest of his days alone on the island, Noland sinks into despair. To emotionally save himself, he creates a friend with whom he can interact: a volleyball named Wilson. Wilson becomes his constant companion, to whom he talks incessantly.

17

Since Cast Away’s release more than a decade ago, “Wilson the volleyball” has become iconic. Numerous YouTube videos spoof Noland’s conversations with Wilson; you can buy Wilson T-shirts, tote bags, and coffee mugs; and in 2014 the Myrtle Beach Pelicans—a minor league branch team of the Texas Rangers—tried to lure pro football star Russell Wilson to its baseball roster by creating a Cast Away-style video with “Wilson” as a football. But beneath the satire and silliness lies a deeper truth about our basic nature. We may be able to physically survive without interpersonal communication with others, but we can’t mentally and emotionally endure such isolation. Interpersonal communication isn’t trivial or incidental; it fulfills a profound human need for connection that we all possess. Of course, it helps us achieve more mundane practical goals as well.

Interpersonal Communication and Human Needs Psychologist Abraham Maslow (1970) suggested that we seek to fulfill a hierarchy of needs in our daily lives. When the most basic needs (at the bottom of the hierarchy) are fulfilled, we turn our attention to pursuing higher-level ones. Interpersonal communication allows us to develop and foster the interactions and relationships that help us fulfill all of these needs. At the foundational level are physical needs, such as air, food, water, sleep, and shelter. If we can’t satisfy these needs, we prioritize them over all others. Once physical needs are met, we concern ourselves with safety needs—such as job stability and protection from violence. Then we seek to address social needs: forming satisfying and healthy emotional bonds with others.

18

Next are self-esteem needs, the desire to have others’ respect and admiration. We fulfill these needs by contributing something of value to the world. Finally, we strive to satisfy self-actualization needs by articulating our unique abilities and giving our best in our work, family, and personal life.

Interpersonal Communication and Specific Goals In addition to enabling us to meet fundamental needs, interpersonal communication helps us meet three types of goals (Clark & Delia, 1979). During interpersonal interactions, you may pursue one or a combination of these goals. The first—self-presentation goals—are desires you have to present yourself in certain ways, so that others perceive you as being a particular type of person. For example, you’re conversing with a roommate who’s just been fired. You want him to know that you’re a supportive friend, so you ask what happened, commiserate, and offer to help him find a new job.

You also have instrumental goals—practical aims you want to achieve or tasks you want to accomplish through a particular interpersonal encounter. If you want to borrow your best friend’s prized Porsche for the weekend, you might remind her of your solid driving record and your sense of responsibility to persuade her to lend you the car.

Finally, you use interpersonal communication to achieve relationship goals—building, maintaining, or terminating bonds with others. For example, if you succeed in borrowing your friend’s car for the weekend and accidentally drive it into a nearby lake, you will likely apologize profusely and offer to pay for repairs to save your friendship.