The Sources of Self

For most of us, critical self-reflection isn’t a new activity. After all, we spend much of our daily lives looking inward, so we feel that we know our selves. But this doesn’t mean that our sense of self is entirely self-determined. Instead, our selves are shaped by at least three powerful outside forces: gender, family, and culture.

44

GENDER AND SELF

Arguably the most profound outside force shaping our sense of self is our gender—the composite of social, psychological, and cultural attributes that characterize us as male or female (Canary, Emmers-Sommer, & Faulkner, 1997). It may strike you as strange to see gender described as an “outside force.” Gender is innate, something you’re born with, right? Actually, scholars distinguish gender, which is largely learned, from biological sex, which we’re born with. Each of us is born with biological sex organs that distinguish us anatomically as male or female. However, our gender is shaped over time through our interactions with others.

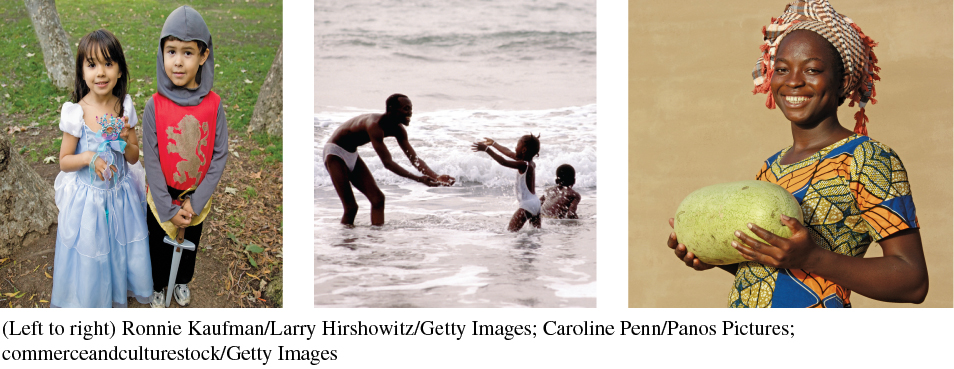

Immediately after birth, we begin a lifelong process of gender socialization, learning from others what it means personally, interpersonally, and culturally to be “male” or “female.” Girls are typically taught feminine behaviors, such as sensitivity to one’s own and others’ emotions, nurturance, and compassion (Lippa, 2002). Boys are usually taught masculine behaviors, learning about assertiveness, competitiveness, and independence. As a result of gender socialization, men and women often end up forming comparatively different self-concepts (Cross & Madson, 1997). For example, women are more likely than men to perceive themselves as connected to others and to assess themselves based on the quality of these interpersonal connections. Men are more likely than women to think of themselves as a composite of their individual achievements, abilities, and beliefs—viewing themselves as separate from other people. However, this doesn’t mean that all men and all women think of themselves in identical ways. Many men and women appreciate and embrace both feminine and masculine characteristics in their self-concepts.

self-reflection

What lessons about gender did you learn from your family when you were growing up? from your friends? Based on these lessons, what aspects of your self did you bolster—or bury—given what others deemed appropriate for your gender? How did these lessons affect how you interpersonally communicate?

FAMILY AND SELF

When we’re born, we have no self-awareness, self-concept, or self-esteem. As we mature, we become aware of ourselves as unique and separate from our environments and begin developing self-concepts. Our caregivers play a crucial role in this process, providing us with ready-made sets of beliefs, attitudes, and values from which we construct our fledgling selves. We also forge emotional bonds with our caregivers, and our communication and interactions with them powerfully shape our beliefs regarding the functions, rewards, and dependability of interpersonal relationships (Bowlby, 1969; Domingue & Mollen, 2009).

45

These beliefs, in turn, help shape two dimensions of our thoughts, feelings, and behavior: attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance (Collins & Feeney, 2004). Attachment anxiety is the degree to which a person fears rejection by relationship partners. If you experience high attachment anxiety, you perceive yourself as unlovable and unworthy—thoughts that may result from being ignored or even abused during childhood. Consequently, you experience chronic fear of abandonment in your close relationships. If you have low attachment anxiety, you feel lovable and worthy of attention—reflections of a supportive and affectionate upbringing. As a result, you feel comfortable and confident in your intimate involvements.

Attachment avoidance is the degree to which someone desires close interpersonal ties. If you have high attachment avoidance, you’ll likely experience little interest in intimacy, preferring solitude instead. Such feelings may stem from childhood neglect or an upbringing that encouraged autonomy. If you experience low attachment avoidance, you seek intimacy and interdependence with others, having learned in childhood that such connections are essential for happiness and well-being.

46

Four attachment styles derive from these two dimensions (Collins & Feeney, 2004; Domingue & Mollen, 2009). Secure attachment individuals are low on both anxiety and avoidance: they’re comfortable with intimacy and seek close ties with others. Secure individuals report warm and supportive relationships, high self-esteem, and confidence in their ability to communicate. When relationship problems arise, they move to resolve them and are willing to solicit support from others. In addition, they are comfortable with sexual intimacy and are unlikely to engage in risky sexual behavior.

Preoccupied attachment adults are high in anxiety and low in avoidance: they desire closeness but are plagued with fear of rejection. They may use sexual contact to satisfy their compulsive need to feel loved. When faced with relationship challenges, preoccupied individuals react with extreme negative emotion and a lack of trust (“I know you don’t love me!”). These individuals often have difficulty maintaining long-term involvements.

People with low anxiety but high avoidance have a dismissive attachment style. They view close relationships as comparatively unimportant, instead prizing and prioritizing self-reliance. Relationship crises evoke hasty exits (“I don’t need this kind of hassle!”), and they are more likely than other attachment styles to engage in casual sexual relationships and to endorse the view that sex without love is positive.

Finally, fearful attachment adults are high in both attachment anxiety and avoidance. They fear rejection and tend to shun relationships. Fearful individuals can develop close ties if the relationship seems to guarantee a lack of rejection, such as when a partner is disabled or otherwise dependent on them. But even then, they suffer from a chronic lack of faith in themselves, their partners, and the relationship’s viability.

CULTURE AND SELF

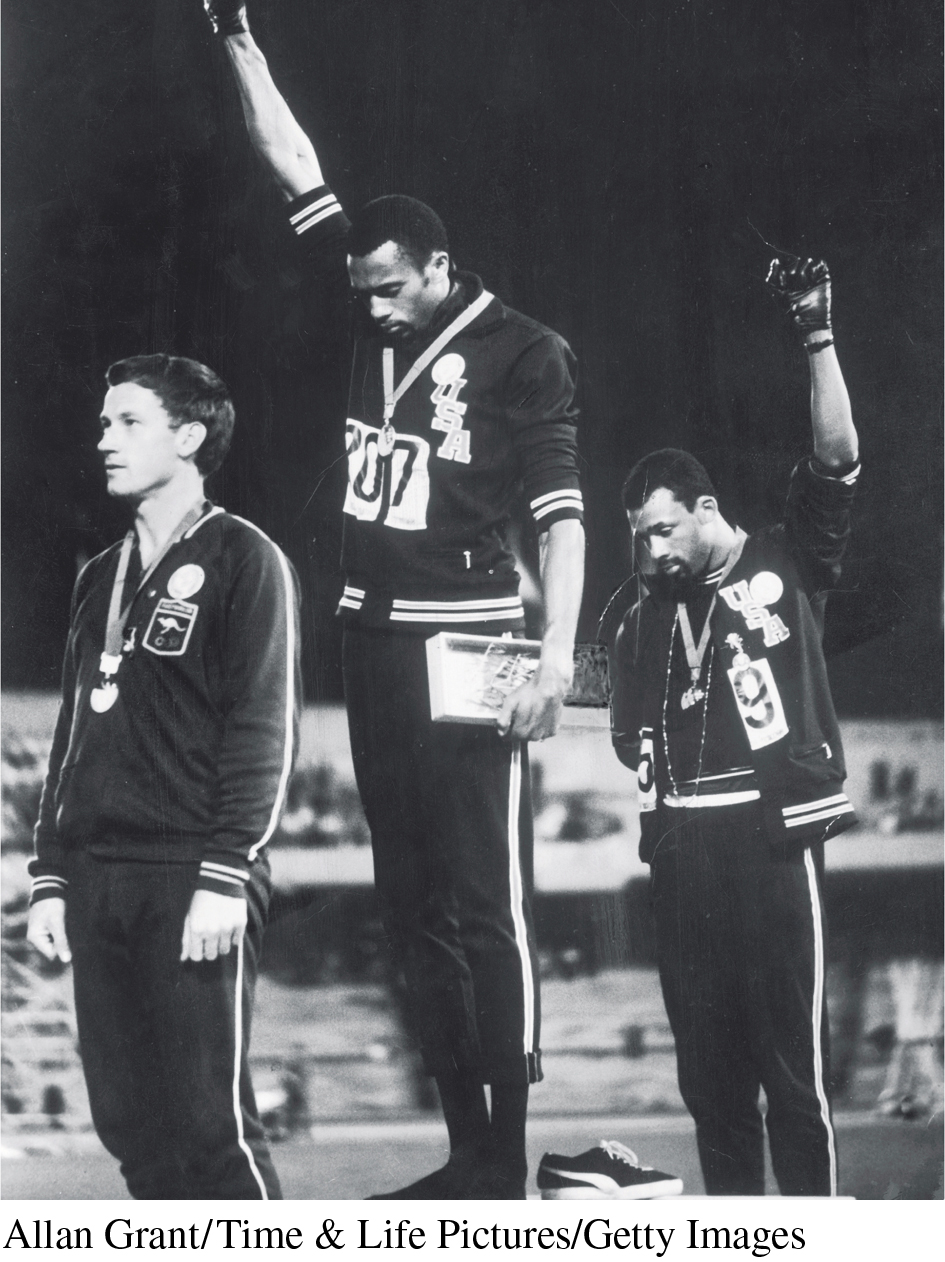

At the 1968 Summer Olympics, U.S. sprinter Tommie Smith won the men’s 200-meter gold medal, and teammate John Carlos won the bronze. During the medal ceremony, as the American flag was raised and “The Star-Spangled Banner” played, both runners closed their eyes, lowered their heads, and raised black-gloved fists. Smith’s right fist represented black power, and Carlos’s left fist represented black unity (Gettings, 2005). The two fists, raised next to each other, created an arch of black unity and power. Smith wore a black scarf around his neck for black pride, and both men wore black socks with no shoes, representing African American poverty. These symbols and gestures, taken together, clearly spoke of the runners’ allegiance to black culture and their protest of the poor treatment of African Americans in the United States (see the photo below).

47

48

self-reflection

When you consider your own cultural background, to which culture do you “pledge allegiance”? How do you communicate this allegiance to others? Have you ever suffered consequences for openly communicating your allegiance to your culture? If so, how?

Many Euro-Americans viewed Smith and Carlos’s behavior at the ceremony as a betrayal of “American” culture. Both men were suspended from the U.S. team and even received death threats. Over time, however, people of all American ethnicities began to sympathize with their protest. Thirty years later, in 1998, Smith and Carlos were commemorated in an anniversary celebration of their protest.

In addition to gender and family, our culture is a powerful source of self. Culture is an established, coherent set of beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices shared by a large group of people (Keesing, 1974). If this strikes you as similar to our definition of self-concept, you’re right; culture is like a collective sense of self shared by a large group of people.

Thinking of culture in this way has three important implications. First, culture includes many types of large-group influences, including your nationality as well as your ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, physical ability, and even age. We learn our cultural beliefs, attitudes, and values from parents, teachers, religious leaders, peers, and the mass media (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003). Second, most of us belong to more than one culture simultaneously—possessing the beliefs, attitudes, and values of each. Third, the various cultures to which we belong sometimes clash. When they do, we often have to choose the culture to which we pledge our primary allegiance.

We’ll be discussing culture in greater depth in Chapter 5, where we’ll consider some of the unique variables of culture that help to define us and communicate our selves to others.