Practicing Responsible Perception

We experience our interpersonal reality—the people around us, our communication with them, and the relationships that result—through the lens of perception. But perception is a product of our own creation, metaphorical clay we can shape in whatever ways we want. At each stage of the perception process, we make choices that empower us to mold our perception in constructive or destructive ways. What do I select as the focus of my attention? What attributions do I make? Do I form initial impressions and cling to them in the face of contradictory evidence? Or do I strive to adapt my impressions of others as I learn new information about them? The choices we make at each of these decision points feed directly into how we communicate with and relate to others. When we negatively stereotype people, for example, or refuse to empathize with someone because he or she is an outgrouper, we immediately destine ourselves to incompetent communication.

To improve our interpersonal communication and relationship decisions, we must practice responsible perception. This means routinely perception-checking and correcting errors. It means striving to adjust our impressions of people as we get to know them better. It means seizing control of our empathy, seeing those who populate our interpersonal world through eyes of empathy, emotionally reaching out to them, and communicating this perspective-taking and empathic concern in open, appropriate ways. Practicing responsible perception means not just mastering the knowledge of perception presented in these pages but also translating this intellectual mastery into active practice during every interpersonal encounter. We all use perception as the basis for our communication and relationship decisions. But when we practice responsible perception, the natural result is more competent communication and wiser relationship choices.

98

POSTSCRIPT

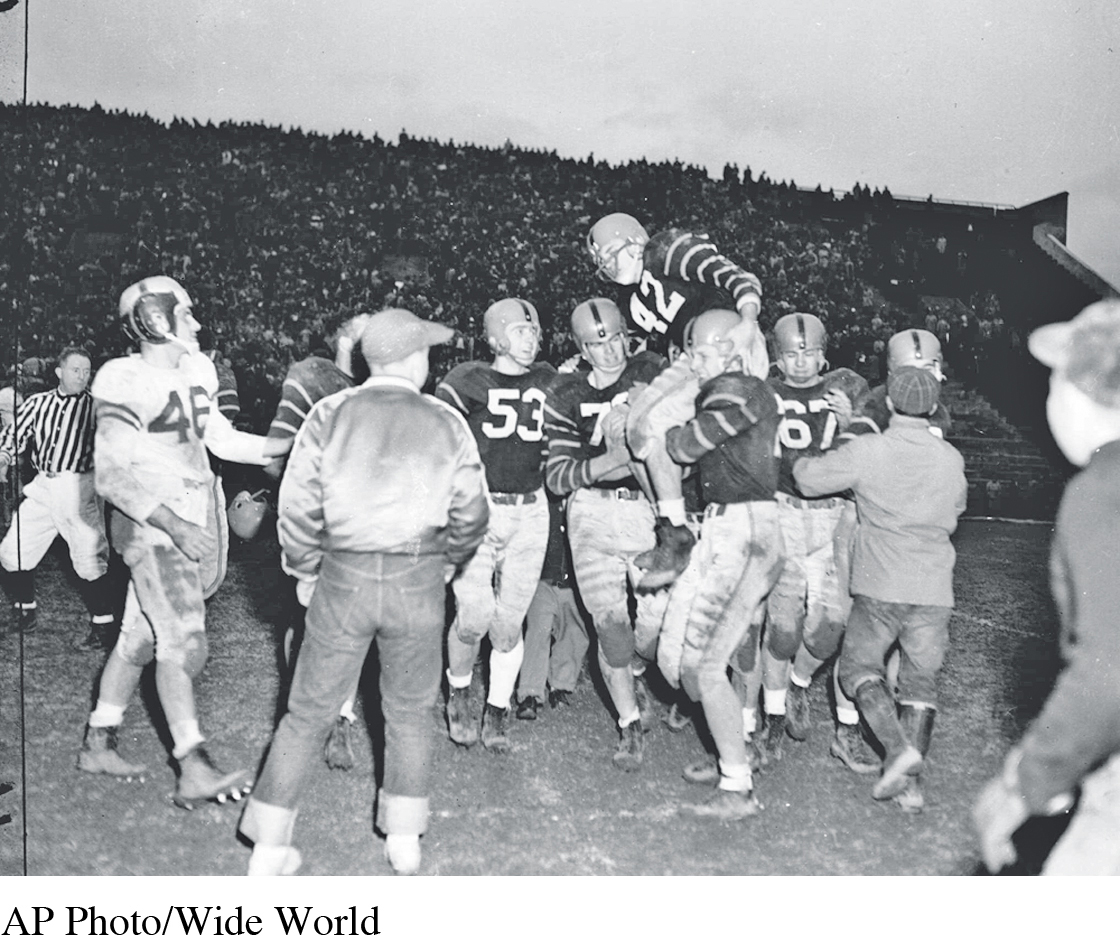

We began this chapter with an account of a football game marked by brutality and accusations of unfair play and an examination of its perceptual aftermath. Following the Dartmouth-Princeton game, fans from both sides felt the opposition had played dirty and that their own team had behaved honorably. Although there was only one game, fans perceived two radically different contests.

When you observe the “game film” of your own life, how often do you perceive others as instigating all of the rough play and penalties you’ve suffered while seeing yourself as blameless? Do you widen the perceptual gulf between yourself and those who see things differently? Or do you seek to bridge that divide by practicing and communicating empathy?

More than 60 years ago, two teams met on a field of play. Decades later, that game—and people’s reactions to it—remind us of our own perceptual limitations and the importance of overcoming them. Although we’ll never agree with everyone about everything that goes on around us, we can strive to understand one another’s viewpoints much of the time. In doing so, we build lives that connect us to others rather than divide us from them.