Cultural Influences on Communication

The hit TV show Modern Family focuses on a California clan whose members have different cultural backgrounds. Euro-American patriarch Jay is married to the (much younger) Gloria, who is originally from Colombia. In addition to their child together, Jay serves as stepfather to Gloria’s son Manny. Jay’s children from a previous marriage also have families of their own. His son Mitchell and his partner, Cam, have an adopted daughter from Vietnam, while Jay’s daughter, Claire, and her goofy husband, Phil, have three biological children. Given this diversity, interpersonal exchanges between the characters routinely cross lines of age, gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation—sometimes at the same time! Not surprisingly, a lot of miscommunication stemming from these differences occurs. For example, Gloria speaks with a Colombian accent and often tangles up her English words. On Halloween, she tells Jay he’s “going to be a gargle.” Manny chimes in to clarify, “She means, ‘gargoyle.’” Later, when a box of Jesus figurines is mysteriously delivered to their house, Jay realizes the error: he had told Gloria to call his secretary and order a box of baby cheeses.

Shows like Modern Family poke lighthearted fun at cultural differences in interpersonal communication. However, the real-world distinctions between cultures can be profound. Scholars suggest that seven cultural characteristics shape our interpersonal communication: individualism versus collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, power distance, high and low context, emotion displays, masculinity versus femininity, and views of time. To build intercultural communication competence, you need to understand these differences. At the same time, keep in mind that while each of these distinctions is presented as polar opposites (high versus low; this versus that), most cultures—and people within them—fall somewhere in between the extremes.

INDIVIDUALISM VERSUS COLLECTIVISM

In individualistic cultures, people tend to value independence and personal achievement. Members of these cultures are encouraged to focus on themselves and their immediate family (Hofstede, 2001), and individual achievement is praised as the highest good (Waterman, 1984). Examples of individualistic countries include the United States, Canada, New Zealand, and Sweden (Hofstede, 2001).

By contrast, in collectivistic cultures, people emphasize group identity (“we” rather than “me”), interpersonal harmony, and the well-being of ingroups (Park & Guan, 2006). If you were raised in a collectivistic culture, you were probably taught that it’s important to belong to groups or “collectives” that look after you in exchange for your loyalty. In collectivistic cultures, people emphasize the goals, needs, and views of groups over those of individuals, and define the highest good as cooperation with others rather than individual achievement. Collectivistic countries include Guatemala, Pakistan, Korea, and Japan (Hofstede, 2001).

Differences between individualistic and collectivistic cultures can powerfully influence people’s behaviors, including which social networking sites they use and how they use them. For instance, people in collectivistic cultures tend to use sites that emphasize group connectedness, whereas those in individualistic cultures tend to use sites that focus on self-expression (Barker & Ota, 2011). American Facebook users devote most of their time on the site describing their own actions and viewpoints as well as personally important events. They also post controversial status updates and express their personal opinions, even if these trigger debate. Japanese users of mixi, meanwhile, carefully edit their profiles so they won’t offend anyone (Barker & Ota, 2011). While American Facebook users often post photos of themselves alone doing various activities, mixi users tend to write in diaries that are shared with their closest friends, boosting ingroup solidarity (Barker & Ota, 2011).

UNCERTAINTY AVOIDANCE

Cultures vary in how much they tolerate and accept unpredictability, known as uncertainty avoidance. As scholar Geert Hofstede explains, “The fundamental issue here is how a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known: should we try to control the future or just let it happen?”1 In high-uncertainty-avoidance cultures (such as Mexico, South Korea, Japan, and Greece), people place a lot of value on control. They define rigid rules and conventions to guide all beliefs and behaviors, and they feel uncomfortable with unusual or innovative ideas. People from such cultures want structure in their organizations, institutions, relationships, and everyday lives (Hofstede, 2001). For example, a coworker raised in a high-uncertainty-avoidance culture would expect everyone assigned to a project to have clear roles and responsibilities, including a designated leader. In his research on organizations, Hofstede found that in high-uncertainty-avoidance cultures, people commit to organizations for long periods of time, expect their job responsibilities to be clearly defined, and strongly believe that organizational rules should not be broken (2001, p. 149). Children raised in such cultures are taught to believe in cultural traditions and practices without ever questioning them.

self-reflection

Consider your own presence on social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram). Does how you portray yourself through social media suggest collectivism or individualism? Does your online portrayal match or clash with how you think of yourself offline?

In low-uncertainty-avoidance cultures (such as Jamaica, Denmark, Sweden, and Ireland), people put more emphasis on letting the future happen without trying to control it (Hofstede, 2001). They care less about rules, they tolerate diverse viewpoints and beliefs, and they welcome innovation and change. They also feel free to question and challenge authority. In addition, they teach their children to think critically about the beliefs and traditions they’re exposed to, rather than automatically following them. Examples of low-uncertainty avoidance cultures include Singapore, Jamaica, and Denmark.

As with each of these cultural distinctions, most countries and people within them fall somewhere between high and low. For instance, both the United States and Canada are moderately uncertainty-avoidant. How does this translate into cultural values? Within both countries, people generally value innovation and new ideas (especially with regard to technology) while emphasizing the importance of laws, rules, and clear guidelines governing behavior, particularly within the workplace.

POWER DISTANCE

self-reflection

What’s your own view of power distance? Are you comfortable communicating with individuals who are better educated or more established than you are? For example, can you chat openly with a professor you admire? How does your cultural or co-cultural identity mesh with your personal feelings about power distance?

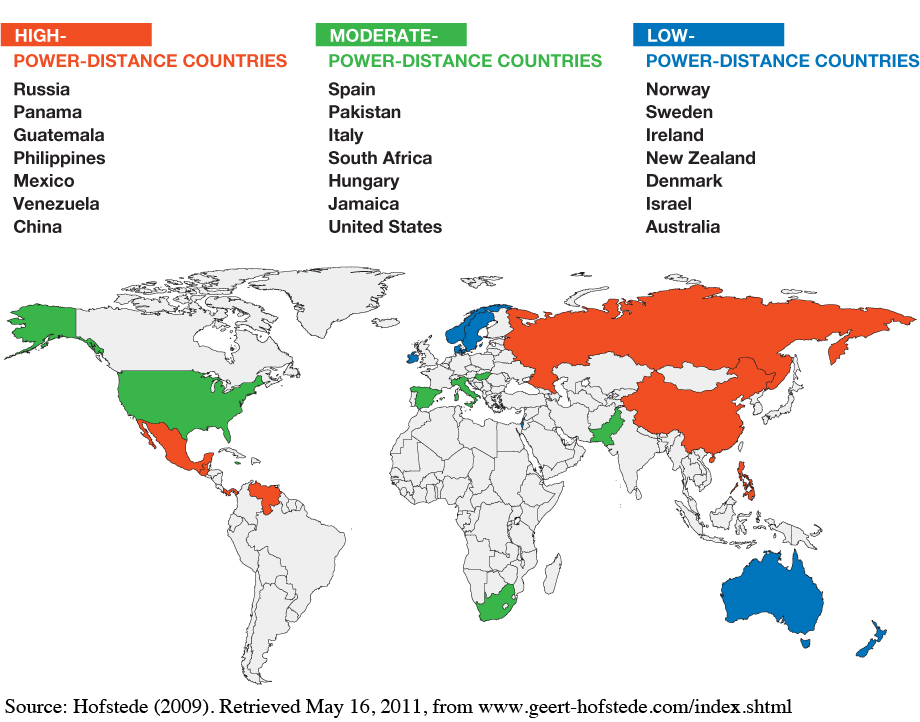

The degree to which people in a particular culture view the unequal distribution of power as acceptable is known as power distance (Hofstede, 1991, 2001). In high-power-distance cultures, it’s considered normal and even desirable for people of different social and professional status to have different levels of power (Ting-Toomey, 2005). In such cultures, people give privileged treatment and extreme respect to those in high-status positions (Ting-Toomey, 1999). They also expect individuals of lesser status to behave humbly, especially around people of higher status, who are expected to act superior.

In low-power-distance cultures, people in high-status positions try to minimize the differences between themselves and lower-status persons by interacting with them in informal ways and treating them as equals (Oetzel et al., 2001). For instance, a high-level marketing executive might chat with the cleaning service workers in her office and invite them to join her for a coffee break. See Figure 5.1 for examples of high- and low-power-distance cultures.

Power distance affects how people deal with interpersonal conflict. In low-power-distance cultures, people with little power may still choose to engage in conflict with high-power people. What’s more, they may do so competitively, confronting high-power people and demanding that their goals be met. For instance, employees may question management decisions and suggest that alternatives be considered, or townspeople may attend a meeting and demand that the mayor address their concerns. These behaviors are much less common in high-power-distance cultures (Bochner & Hesketh, 1994), where low-power people are more likely to either avoid conflict with high-power people or accommodate them when conflict arises. (For more insight on how people approach conflict, see Chapter 9.)

Power distance also influences how people communicate in close relationships, especially families. In traditional Mexican culture, for instance, the value of respeto (respect) emphasizes power distance between younger people and their elders (Delgado-Gaitan, 1993). As part of respeto, children are expected to defer to elders’ authority and to avoid openly disagreeing with them. In contrast, many Euro-Americans believe that once children reach adulthood, power in family relationships should be balanced, with children and their elders treating one another as equals (Kagawa & McCornack, 2004).

HIGH AND LOW CONTEXT

Cultures can also be described as high or low context. In high-context cultures, such as China, Korea, and Japan, people presume that others within the culture will share their viewpoints and thus perceive situations (contexts) in very much the same way. (High-context cultures are often collectivistic as well.) Consequently, people in such cultures often talk indirectly, using hints or suggestions to convey meanings—the presumption being that because individuals share the same contextual view, they automatically know what another person is trying to say. Relatively vague, ambiguous language—and even silence—is frequently used, and there’s no need to provide a lot of explicit information within messages.

In low-context cultures, people tend not to presume that others share their beliefs, attitudes, and values. So they strive to be informative, clear, and direct in their communication (Hall & Hall, 1987). Many low-context cultures are also individualistic; as a result, people openly express their views and try to persuade others to accept them (Hall, 1976, 1997a). Within such cultures, which include Germany, Scandinavia, Canada, and the United States, people work to make important information obvious, rather than hinting or implying.

How does the difference between high-context and low-context cultures play out in real-world encounters? Consider the experiences of my friend and former graduate student Naomi Kagawa, who is now a Japanese communication professor. Growing up in Japan, a high-context culture, Naomi learned to reject requests by using words equivalent to OK or sure in order to maintain the harmony of the encounter. These words, however, are accompanied by subtle vocal tones that imply no. Because all members of the culture understand this practice, they recognize that such seeming assents are actually rejections. In contrast, in the United States—a low-context culture—people don’t share similar knowledge and beliefs, so they spell things out much more explicitly. People often come right out and say no, then apologize and explain why they can’t grant the request. When Naomi first visited the United States, this difference caused misunderstandings in her interpersonal interactions. She rejected unwanted requests by saying “OK,” only to find that people presumed she was consenting rather than refusing. And she was surprised, even shocked, when people rejected her requests by explicitly saying no.