Characteristics of Verbal Communication

When we think of what it means to communicate, what often leaps to mind is the exchange of spoken or written language with others during interactions, known as verbal communication. Across any given day, we use words to communicate with others in our lives in various face-to-face or mediated contexts. During each of these encounters, we tailor our language in creative ways, depending on whom we’re speaking with. We shift grammar, word choices, and sometimes even the entire language itself—for example, firing off a Spanish text message to one friend and an English text to another.

self-reflection

How is the language that you use different when talking with professors versus talking to your best friend or romantic partner? Which type of language makes you feel more comfortable or close to the other person? What does this tell you about the relationship between language and intimacy?

Because verbal communication is defined by our use of language, the first step toward improving our verbal communication is to deepen our understanding of language.

LANGUAGE IS SYMBOLIC

Take a quick look around you. You’ll likely see a wealth of images: this book, the surface on which it (or your device) rests, and perhaps your roommate or romantic partner. You might experience thoughts and emotions related to what you’re seeing—memories of your roommate asking to borrow your car or feelings of love toward your partner. Now imagine communicating all of this to others. To do so, you need words to represent these things: “roommate,” “lover,” “borrow,” “car,” “love,” and so forth. Whenever we use items to represent other things, they are considered symbols. In verbal communication, words are the primary symbols that we use to represent people, objects, events, and ideas (Foss, Foss, & Trapp, 1991).

192

All languages are basically giant collections of symbols in the form of words that allow us to communicate with one another. When we agree with others on the meanings of words, we communicate easily. Your friend probably knows exactly what you mean by the word roommate, so when you use it, misunderstanding is unlikely. But some words have several possible meanings, making confusion possible. For instance, in English, the word table might mean a piece of furniture, an element in a textbook, or a verb referring to the need to end talk (“Let’s table this discussion until our next meeting”). For words that have multiple meanings, we rely on the surrounding context to help clarify meaning. If you’re in a classroom and the professor says, “Turn to Table 3 on page 47,” you aren’t likely to search the room for furniture.

193

LANGUAGE IS GOVERNED BY RULES

When we use language, we follow rules. Rules govern the meaning of words, the way we arrange words into phrases and sentences, and the order in which we exchange words with others during conversations. Constitutive rules define word meaning: they tell us which words represent which objects (Searle, 1965). For example, a constitutive rule in the English language is “The word dog refers to a domestic canine.” Whenever you learn the vocabulary of a language—words and their corresponding meanings—you’re learning the constitutive rules for that language.

Regulative rules govern how we use language when we verbally communicate. They’re the traffic laws controlling language use—the dos and don’ts. Regulative rules guide everything from spelling (“i before e except after c”) to sentence structure (“The article the or a must come before the noun dog”) to conversation (“If someone asks you a question, you should answer”).

To communicate competently, you must understand and follow the constitutive and regulative rules governing the language you’re using. If you don’t know which words represent which meanings (constitutive rules), you can’t send clear messages to others or understand messages delivered by others. Likewise, without knowing how to form a grammatically correct sentence and when to say particular things (regulative rules), you can’t communicate clearly with others or accurately interpret their messages to you.

LANGUAGE IS FLEXIBLE

Although all languages have constitutive and regulative rules, people often bend those rules. Partners in close relationships, for example, often create personal idioms—words and phrases that have unique meanings to them (Bell, Buerkel-Rothfuss, & Gore, 1987). One study found that the average romantic couple creates more than a half dozen idioms, the most common being nicknames such as Honeybear or Pookie. Such shared linguistic creativity is both reflective and reinforcing of intimacy and relationship satisfaction. For example, happily married couples report using more idioms than unhappily married couples, and partners in the early stages of marriage (i.e., the honeymoon phase) use the most idioms of all (Bruess & Pearson, 1993).

194

LANGUAGE IS CULTURAL

Members of a culture use language to communicate their thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, and values with one another, and thereby reinforce their collective sense of cultural identity (Whorf, 1952). Consequently, the language you speak (English, Spanish, Mandarin, Urdu), the words you choose (proper, slang, profane), and the grammar you use (formal, informal) all announce to others: “This is who I am! This is my cultural heritage!”

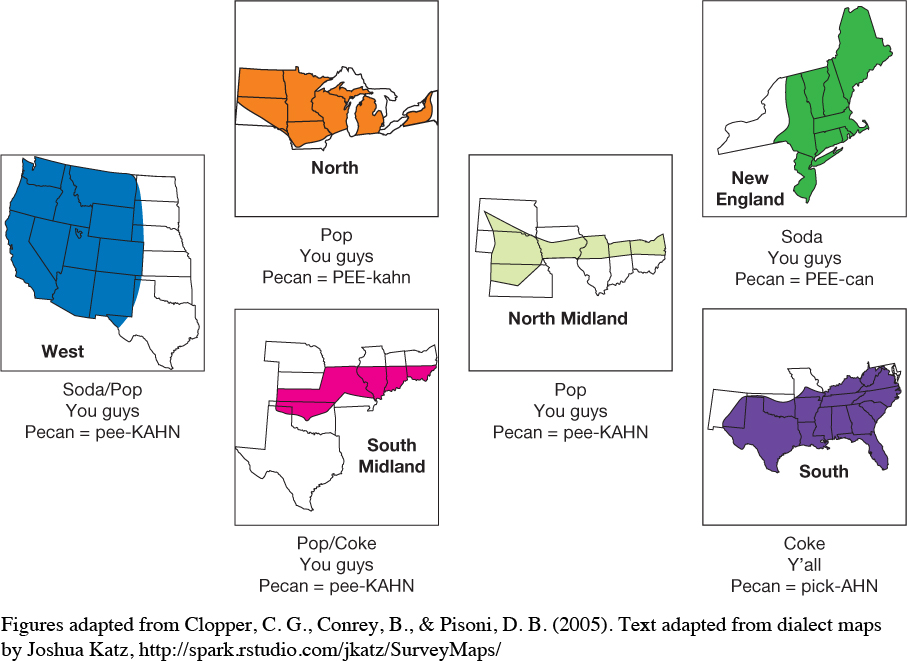

Each language reflects distinct sets of cultural beliefs and values. However, a large group of people within a particular culture who speak the same language may, over time, develop their own variations on that language, known as dialects (Gleason, 1989). Dialects may include unique phrases, words, and pronunciations (such as accents). Dialects can be shared by people living in a certain region (midwestern, southern, or northeastern United States), people with a common socioeconomic status (upper-middle-class suburban, working-class urban), or people of similar ethnic or religious ancestry (Yiddish English, Irish English, Amish English) (Chen & Starosta, 2005). Within the United States, for example, six regional dialects exist (see Figure 7.1), but the two most easily recognizable are New England and the South (Clopper, Conrey, & Pisoni, 2005). These two dialects are so distinct that most people can accurately identify them after hearing just one spoken sentence, regardless of whether the speaker is male or female (Clopper et al., 2005).

195

We often judge others who use dialects similar to our own as ingroupers, and we’re inclined to make positive judgments about them as a result (Delia, 1972; Lev-Ari & Keysar, 2010). In a parallel fashion, we tend to judge those with dissimilar dialects as outgroupers, and make negative judgments about them. Keep this tendency in mind when you’re speaking with people who don’t share your dialect, and resist the temptation to make negative judgments about them. For additional ideas on dealing with ingroup or outgroup perceptions, see Chapter 3.

LANGUAGE EVOLVES

Each year, the American Dialect Society selects a Word of the Year. Recent winners include tweet, a “short, timely message sent via the Twitter.com service,” and app, “an abbreviated form of application, a software program for a computer or phone operating system.” Even the Oxford English Dictionary—the resource that defines the English language—annually announces what new terms have officially been added to the English vocabulary. In 2013, this included the word selfie (“a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website”).

Many people view language as fixed. But in fact, language constantly changes. A particular language’s constitutive rules—which define the meanings of words—may shift. As time passes and technology changes, people add new words to their language (tweet, app, cyberbullying, sexting, selfie) and discard old ones. Sometimes people create new phrases, such as helicopter parent, that eventually see wide use. Other times, speakers of a language borrow words and phrases from other languages and incorporate them into their own.

self-reflection

Which dialect best describes your own speech? Have you ever experienced judgment from others because of the way you speak? How did you respond? If you’re being honest, are there dialects that cause you to judge outgroupers negatively? How might you overcome this?

Consider how English-speakers have borrowed from other languages: If you tell friends that you want to take a whirl around the United States, you’re using Norse (Viking) words; and if your trip takes you to Wisconsin, Oregon, and Wyoming, you’re visiting places with Native American names.2 If you stop at a café and request a cup of tea along the way, you’re speaking Amoy (eastern China), but if you ask the waiter to spike your coffee with alcohol, you’re using Arabic. If, at the end of the trip, you express an eagerness to return to your job, you’re employing Breton (western France), but if you call in sick and tell your manager that you have influenza, you’re speaking Italian.

196

A language’s regulative rules also change. When you learned to speak and write English, for example, you were probably taught that they is inappropriate as a singular pronoun. But before the 1850s, people commonly used they as the singular pronoun for individuals whose gender was unknown—for example, “the owner went out to the stables, where they fed the horses” (Spender, 1990). In 1850, male grammarians petitioned the British Parliament to pass a law declaring that all gender-indeterminate references be labeled he instead of they (Spender, 1990). Since that time, teachers of English worldwide have taught their students that they used as a singular pronoun is “not proper.”