Performing Actions, Crafting Conversations, and Maintaining Relationships

201

PERFORMING ACTIONS

A fourth function of verbal communication is that it enables us to take action. We make requests, issue invitations, deliver commands, or even taunt—as Ali did to his competitors. We also try to influence others’ behaviors. We want our listeners to grant our requests, accept our invitations, obey our commands, or suffer from our curses. The actions that we perform with language are called speech acts (Searle, 1969). (See Table 7.1 for types of speech acts.)

During interpersonal encounters, the structure of our back-and-forth exchange is based on the speech acts we perform (Jacobs, 1994; Levinson, 1985). When your professor asks you a question, how do you know what to do next? You recognize that the words she has spoken constitute a “question,” and you realize that an “answer” is expected as the relevant response. Similarly, when your best friend texts you and inquires, “Can I borrow your car tonight?” you immediately recognize his message as a “request.” You also understand that two speech acts are possible as relevant responses: “granting” his request (“no problem”) or “rejecting” it (“I don’t think so”).

| Act | Function | Forms | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representative | Commits the speaker to the truth of what has been said | Assertions, Conclusions | “It sure is a beautiful day.” |

| Directive | Attempts to get listeners to do things | Questions, Requests, Commands | “Can you loan me five dollars?” |

| Commissive | Commits speakers to future action | Promises, Threats | “I will always love you, no matter what happens.” |

| Expressive | Conveys a psychological or emotional state that the speaker is experiencing | Thanks, Apologies, Congratulations | “Thank you so much for the wonderful gift!” |

| Declarative | Produces dramatic, observable effects | Marriage Pronouncements, Firing Declarations | “From this point onward, you are no longer an employee of this organization.” |

| Note: The information in this table is adapted from Searle (1976). | |||

CRAFTING CONVERSATIONS

A fifth function served by language is that it allows us to craft conversations. Language meanings, thoughts, names, and acts don’t happen in the abstract; they occur within conversations. Although each of us intuitively knows what a conversation is, scholars suggest four characteristics fundamental to conversation (Nofsinger, 1999). First, conversations are interactive. At least two people must participate in the exchange for it to count as a conversation, and participants must take turns exchanging messages.

202

Second, conversations are locally managed. Local management means that we make decisions regarding who gets to speak when, and for how long, each time we exchange turns. This makes conversation different from other verbal exchanges, such as debate, in which the order and length of turns are decided before the event begins, and drama, in which people speak words that have been written down in advance.

skillspractice

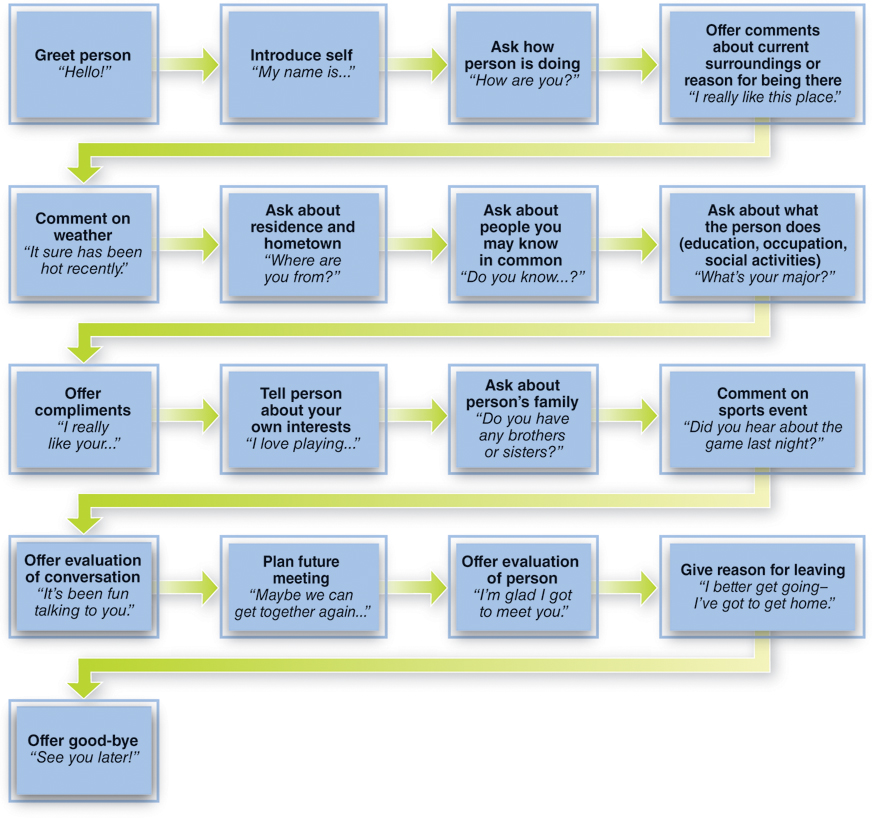

Ensuring Competent First Encounters

Putting Kathy Kellermann’s Research on Conversation Scripts into Action

Identify a new acquaintance with whom you would like to interact.

Greet the person, introduce yourself, and ask how he or she is doing.

Discuss current surroundings, the weather, and hometowns.

Ask about interests, school, sports, and social activities, all the while looking for points of commonality and ways to compliment the person.

Raise the possibility of future interaction, express gratitude for the current conversation, and exit with a friendly “Good-bye.”

Third, conversation is universal. Conversation forms the foundation for most forms of interpersonal communication and for social organization generally. Our relationships and our places in society are created and maintained through conversations.

203

Fourth, conversations often adhere to scripts—rigidly structured patterns of talk. This is especially true in first encounters, when you are trying to reduce uncertainty. For example, the topics that college students discuss when they first meet often follow a set script. Communication researcher Kathy Kellermann (1991) conducted several studies looking at the first conversations of college students and found that 95 percent of the topic changes followed the same pattern regardless of gender, age, race, or geographic region (see Figure 7.2.). This suggests that a critical aspect of appropriately constructing conversations is grasping and following relevant conversational scripts.

Does the fact that we frequently use scripts to guide our conversations mean this type of communication is inauthentic? If you expect more from an exchange than a prepackaged response, scripted communication may strike you as such. However, communication scripts allow us to relevantly and efficiently exchange greetings, respond to simple questions and answers, trade pleasantries, and get to know people in a preliminary fashion without putting much active thought into our communication. This saves us from mental exertion and allows us to focus our energy on more involved or important interpersonal encounters.

MANAGING RELATIONSHIPS

In Alice Sebold’s (2002) award-winning novel The Lovely Bones, Indian high school student Ray Singh is desperately in love with the central character, Susie Salmon. Seeing her sneaking into school late one morning (while he himself is cutting class and hiding out in the school theater), he decides to declare his feelings.

“You are beautiful, Susie Salmon!” I heard the voice but could not place it immediately. I looked around me. “Here,” the voice said. I looked up and saw the head and torso of Ray Singh leaning out over the top of the scaffold above me. “Hello,” he said. I knew Ray had a crush on me. He had moved from England the year before, but was born in India. That someone could have the face of one country and the voice of another and then move to a third was too incredible for me to fathom. It made him immediately cool. Plus, he seemed eight hundred times smarter than the rest of us, and he had a crush on me. That morning, when he spoke to me from above, my heart plunged to the floor. (p. 82)

self-reflection

Consider a recent instance in which a relationship of yours suddenly changed direction, either for better or for worse. What was said that triggered this turning point? How did the words that were exchanged impact intimacy? What does this tell you about the role that language plays in managing relationships?

Verbal communication’s final, and arguably most profound, function in our lives is to help us manage our relationships. We use language to create relationships by declaring powerful, intimate feelings to others, such as “You are beautiful!” Verbal communication is the principal means through which we maintain our ongoing relationships with lovers, family members, friends, and coworkers (Stafford, 2010). For example, romantic partners who verbally communicate frequently with each other, and with their partners’ friends and families, experience less uncertainty in their relationships and are not as likely to break up as those who verbally communicate less often (Parks, 2007). Finally, most of the heartbreaks we’ll experience in our lives are preceded by verbal messages that state, in one form or another, “It’s over.” We’ll discuss more about how we forge, maintain, and end our relationships in Chapters 10 through 12, and the Relationships in the Workplace appendix.

204